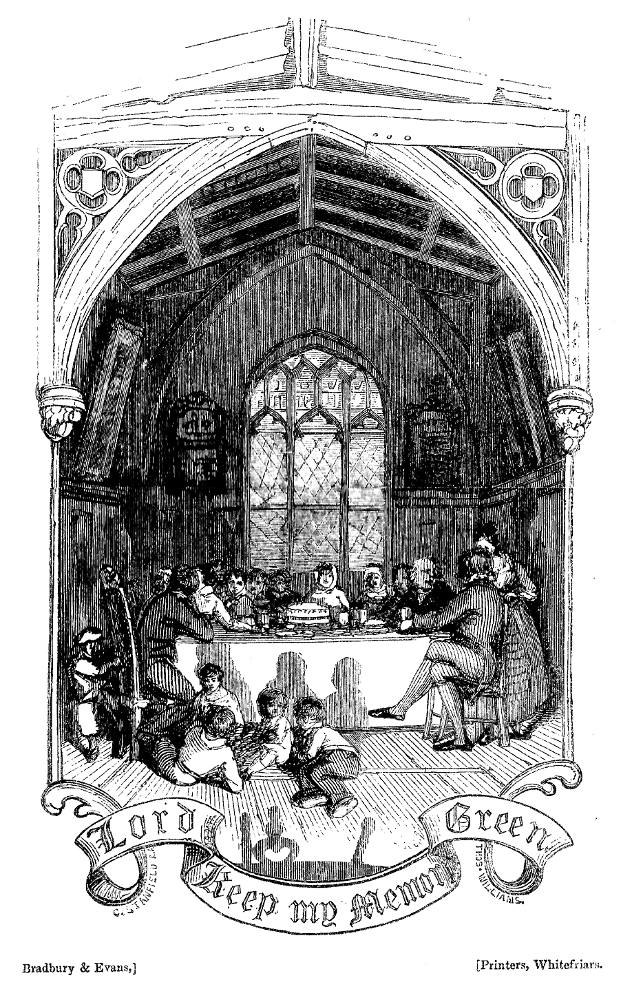

"Lord, keep my Memory Green!" — Barnard's seventh illustration for Dickens's "The Haunted Man" in the Household Edition of "Christmas Books" (1878) (original) (raw)

The Passage Illustrated in "Chapter III. The Gift Bestowed"

" — It was quite a pleasure to know that one of our founders — or, more correctly speaking," said the old man, with a great glory in his subject and his knowledge of it, "one of the learned gentlemen that helped endow us in Queen Elizabeth's time, for we were founded afore her day — left in his will, among the other bequests he made us, so much to buy holly, for garnishing the walls and windows, come Christmas. There was something homely and friendly in it. Being but strange here, then, and coming at Christmas time, we took a liking for his very picter that hangs in what used to be, anciently, afore our ten poor gentlemen commuted for an annual stipend in money, our great Dinner Hall. A sedate gentleman in a peaked beard, with a ruff round his neck, and a scroll below him, in old English letters, 'Lord! keep my memory green!' You know all about him, Mr. Redlaw?"

"I know the portrait hangs there, Philip."

"Yes, sure, it’s the second on the right, above the panelling. I was going to say — he has helped to keep my memory green, I thank him; for going round the building every year, as I’m a doing now, and freshening up the bare rooms with these branches and berries, freshens up my bare old brain." [Chapter 1, British Household Edition, p. 162]

However, the seventh and final Barnard illustration for The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain — Barnard has dispensed with the subtitle in Gothic letters — is also the closing image for the entire volume. The second passage which it realises comes directly before it.

The Repeated Passage Illustrated in "The Gift Reversed" — Text and Illustration

Deepened in its gravity by the fire-light, and gazing from the darkness of the paneled wall like life, the sedate face in the portrait, with the beard and ruff, looked down at them from under its verdant wreath of holly, as they looked up at it; and, clear and plain below, as if a voice had uttered them, were the words:

"Lord keep my Memory Green!" [Chapter III, "The Gift Reversed," 200]

As David Parker notes, “his entreaty closes the book . . . , and sustains the heartfelt calm of its ending, by containing layer upon layer of meaning beneath a surface of folksy piety” (269). Parker also points out that the motto has, in fact, at least two meanings, for the Renaissance "benefactor" undoubtedly wished to be remembered by succeeding generations for his endowment; however, for so many characters in the book, not the least Philip Swidger and Professor Redlaw, the aphorism would suggest, "Do not let me forget."

The story, we are reminded, is about keeping the faculty of memory itself "green," in order to preserve an outlook upon the world and its inhabitants, healthy morally and spiritually.

Ambiguity and association make the prayer that ends The Haunted Man rich in meaning, despite superficial simplicity. One further meaning, more overt at the end of Dickens's next text about Christmas, is perhaps hinted at here. On Christmas Day, Christians decorate their homes with holly to evoke one memory above all others. For such readers, the inscription beneath the portrait is, not least, a reminder of the incarnation of Christ, whose example in spires Redlaw's redemption. [Parker, 260-61]

The dominating portrait, like its caption, is alluded to both at the beginning of the novella, and at the conclusion; in fact, the Gothic letters of the subtitle on the Bradbury and Evans title-page, "A Fancy for Christmas-Time," may constitute our first clue to the thematic significance of the other phrase set in Gothic type at the very conclusion. The first allusion to the portrait and its homiletic caption appears early on in "The Gift Bestowed."

Barnard in the final illustration for The Christmas Books(1878) repeats these words, omitting the vocative comma after "Lord," in the caption under the portrait of a substantial, bearded Elizabethan gentleman, with fur collar, staff, and chain of office, and bearing a torch.

Barnard's illustration of the Benefactor's Portrait and Clarkson Stanfield's painterly realisation of "The Christmas Party in the Great Dinner Hall" (1848)

Although Dickens had originally assigned the closing illustration to John Leech, fearing that Leech, undoubtedly very busy with the Christmas illustrations for the large-scale London magazine of humour, Punch, suggested that this final plate be assigned instead to marinescape painter Clarkson Stanfield.

Stanfield's elegant architectural studies of the exterior and interior ofThe Old College versus Barnard's individual portrait of the Founder of the College.

The original Clarkson Stanfieldarchitectural study of 1848 diminishes the importance of the characters within it. However, as Parker notes, the elegant beams and ceiling, lit by a stained-glass window to the rear, are entirely consistent with the somber mood of the closing, whose final words are also "Lord, Keep my Memory Green" (200 in the Household Edition; 188 in the 1848 edition).

Together with innumerable Swidgers, the main characters gather for Christmas dinner in the college hall. The mood is pensive rather than jubilant. Strong feelings are indicated, but with restraint. we are offered a measured contrast, deeply soothing in effect, to the naked despondency that has hitherto prevailed. [Parker 259]

It is possible to argue that Stanfield deliberately subordinated the figures in the picture to the physical setting, whose hammer-beams, oak pillars, wainscotted panneling, and triple-stained-glass window are legacies of the past, in order to emphasize the theme on the scroll. The only obvious identifications are Milly and Redlaw (right) and the five children to the left, who are probably Tetterbys. For his part, Barnard has decided to dispense with the characters entirely, and focus on the presiding genius of the seasonal celebration, the figure from three centuries before who is remembered and, as it were, recalled to life every December 25th by the seasonal greenery surrounding him. His portrait is "kept green," and his presence in the annual feast acknowledged.

As Parker points out, Dickens probably had a specific set of London buildings — and probably two different sets of Renaissance buildings — in mind for the novella's principal setting:

The college is evidently a conflation of the Charterhouse and Gresham College. Originally a Carthusian priory, the Charterhouse, in Clerkenwell, was refounded in 1611 by Thomas Sutton, as a school, and as a refuge for decayed bachelors or widowers. Damaged by bombing in 1941, its buildings in the early nineteenth century included a fifteenth century gatehouse, courts, and cloisters [suggested in Stanfield's "The Exterior of the Old College"], and a splendid sixteenth-century great hall, used by the brethren for dining. Gresham College was established in the City of London in 1579, by the will of Sir Thomas Gresham, for the delivery of public lectures on divinity, astronomy, music, geometry, physic, law, and rhetoric. [322]

It is perfectly reasonable to conjecture, then, as to whether Fred Barnard had an actual portrait of Thomas Sutton or Sir Thomas Gresham in mind, or whether the late nineteenth century illustrator has, as it were, synthesised a number of Elizabethan and Jacobean portraits, as Dickens and Stanfield had synthesised Charterhouse and Gresham College. In fact, the luxurious, forking beard of the gentleman in Barnard's idealised portrait is highly reminiscent of Gresham's own in maturity, while the costume that Barnard has given his figure resembles both that in Portrait of Thomas Sutton (prominently featuring a starched ruff of the sort mentioned by Dickens) at Charterhouse, and that in the Portrait of Sir Thomas Gresham (c. 1519-79) from Memoirs of the Court of Queen Elizabeth after the portrait by Antonio Mor, published in 1825. Compare, for example, the portrait of Gresham in the National Portrait Gallery, London, Sir Thomas Gresham by Unknown Anglo-Netherlandish artist circa 1565, a three-quarter-length portrait of a distinguished nobleman in his mid-forties. Barnard, academically trained and a Londoner, would probably have seen both the National Portrait Gallery portrait of Sutton and this and other portraits of Gresham, and would have made the connection to The Old Collegeof Dickens's fifth and final Christmas Book. Moreover, The London Illustrated News published a study of Gresham together with his portrait in 1866, commemorating his founding of the Royal Exchange, modelled on the Antwerp bourse, in 1565.

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Illustrations in Dickens's The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain: Public and Private Spheres and Spaces."Dickens Studies Annual 36 (2005), 75-123.

Brereton, D. N. "Introduction." Charles Dickens's Christmas Books. London and Glasgow: Collins Clear-Type Press, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and his Original Illustrators. Columbus: University of Ohio Press, 1980.

Cook, James. Bibliography of the Writings of Dickens. London: Frank Kerslake, 1879. As given in Publishers' Circular The English Catalogue of Books.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

_______. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. 19 vols. New York: Harper & Bros., 1876. Vol. III, 143-175.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878. Vol. XVII. Pp. 157-200.

Dickens, Charles. The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain. Illustrated by John Leech, Frank Stone, John Tenniel, and Clarkson Stanfield. Engraved by Martin & Corbould, T. Williams, Smith & Chellnam, and Dalziel. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1848.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book, 1912.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Parker, David. "Christmas Books and Stories, 1844 to 1854." Christmas and Charles Dickens. New York: AMS Press, 2005. Pp. 221-282.

Slater, Michael. "Notes to The Haunted Man." Dickens's Christmas Books. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1971. Rpt., 1978. Vol. 2: 365-366.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Created 6 September 2012

Last modified 8 June 2024