"'What do you call this?' said Joe" — C. E. Brock's twelfth illustration for "A Christmas Carol" (1905) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated: The Vultures Gather

"And now undo my bundle, Joe," said the first woman.

Joe went down on his knees for the greater convenience of opening it, and having unfastened a great many knots, dragged out a large and heavy roll of some dark stuff.

"What do you call this?" said Joe. "Bed-curtains?"

"Ah!" returned the woman, laughing and leaning forward on her crossed arms. "Bed-curtains!"

"You don't mean to say you took 'em down, rings and all, with him lying there?" said Joe.

"Yes, I do," replied the woman. "Why not?"

"You were born to make your fortune," said Joe, "and you'll certainly do it." [Stave Four, "The Last of the Spirits," 81-82]

Commentary

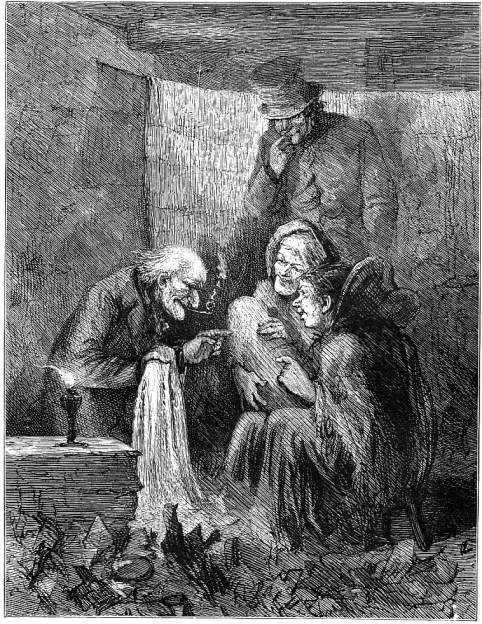

Here once again is the sordid cast of characters who vulture-like have descended upon Old Joe's marine-store or rag-and-bone shop in the East End, "this den of infamous resort" (79) where second-hand personal property is speedily converted into cash. E. C. Brock, working in 1905, had several possible models from which to work, even though Dickens's original illustrator, John Leech had not realised the grisly scene of capitalistic transaction. Since he is not likely to have seen the distorted visages of Mrs. Dilber and her confederates ofSol Eytinge, Junior in the 1868 Ticknor-Fields edition, his chief model was undoubtedly the Fred Barnard composite woodblock engraving in the 1878 British Household Edition of Chapman and Hall, "What do you call this?" said Joe. "Bed-curtains?" (see below), although he probably had access to the Charles Green lithograph composed in 1892,Vision of the Rag Shop: "What do you call this?" said Joe (see below). Brock's interpretation, in turn, probably influenced the 1915 pen-and-ink watercolour lithograph by Arthur Rackham. The brilliance of Brock's drawing is its complete integration into the text so that the reader decodes the passage and the image simultaneously rather than proleptically or analeptically.

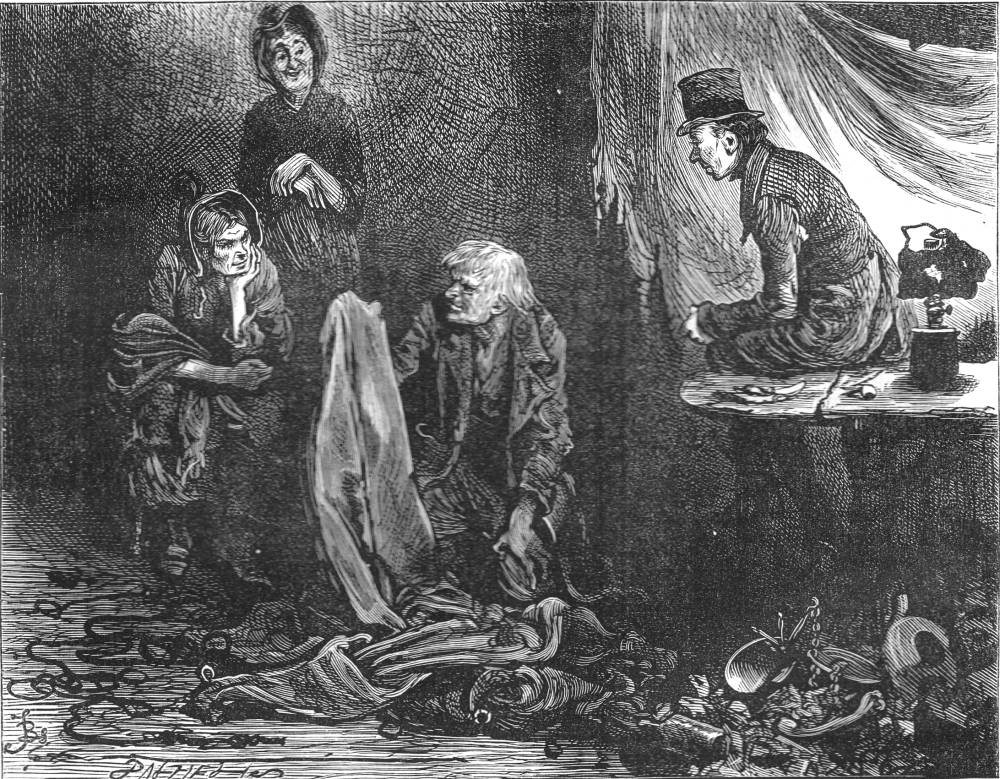

Although Green's more realistic interpretation involves less distortion and visual editorializing, Fred Barnard and Sol Eytinge, Jr., almost seem to relish the grotesquerie and sordidness of the characters and setting. The rag-and-bone shop in the depths of the hellish London slums would seem to be the complete antithesis of the Royal Stock Exchange, depicted in the previous scene: in fact, despite the binary opposites of light and dark, rich and poor, and respectability and corruption, both plates depict places of business that are necessary corollaries of the capitalist system of which Scrooge has heretofore been a leading exponent. Joe, like Marley and Scrooge, is a good man of business who knows that the value of a thing is only what somebody is prepared to pay for it. In Eytinge's Old Joe (see below), the scruffy pawnbroker, a hideous, hook-nosed old rascal, examines Scrooge's bedsheets; he presides over a shop filled with rags, rather than, as in Barnard's composite woodblock-engraving, scrap metal, since Dickens specifically mentions piles of various metal objects. In Brock's dynamic sketch, however, the illustrator provides only a few bottles and chains (lower right) to set the scene, and his focus is the two foregrounded figures, Mrs. Dilber, the laundress, watching sharply as Joe, right, holds up the bed-curtains for appraisal. The watchers in the background are the undertaker's man, dressed in professional black, and the char-lady, also in a bonnet of the style worn in the 1840s.

As in the treatments of the scene by Barnard and Green, none of Brock's participants in the bartering could justly be designated an "obscene demon" (83); they are merely tough-minded conductors of business and agents of commerce, not so different (but for their less than elegant attire) from the businessmen of Brock's previous scene. Scrooge, a dealer in commodities, has himself in death become the source of a commodity, Barnard implies. The triumph of the scene, a parody of Twelfth Night celebrations and "a mock Adoration on a future Twelfth Night Epiphany" (Patten, 187) is the artist's ability to throw over the frowsy and unpleasant moment of choric commentary a certain vividness that transmutes the unsavoury side of the capitalistic enterprise into the engagingly beautiful as we and Scrooge observe the final destination of Scrooge's belongings, crystallising the dreamer's "vague uncertain horror" (27) at the beginning of Stave Four into a powerfully conceived night scene in what Robert L. Patten appropriately terms "the city's colon" (186).

Relevant illustrations from various editions

Left: Rackham's atmospheric interpretation of the characters and setting of the back parlour of "this den of imfamous resort," "What do you call this?' said Joe. "Bed-curtains" (1915). Right: Eytinge depicts the same scene but, unlike Brock, focusses upon the hideous proprietor rather than the object appraised, in Old Joe's, in the 1868 single-volume edition.

Above: Barnard's full-page rendering of the scene at the rag-and-bone shop as a series of commercial transactions, "What do you call this?" said Joe. "Bed-curtains?" (1878).

Above: Green's full-page rendering of the scene as a counterpoint to the previous discussion of Scrooge's death at the 'Change, Vision of the Rag Shop: "What do you call this?" said Joe (1892).

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books, illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

___. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

___. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

___. Christmas Books, illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

___. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

___. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas, illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

___. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas, illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

___. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth, illustrated by C. E. [Charles Edmund] Brock. London: J. M. Dent, 1905; New York: Dutton, rpt., 1963.

___. A Christmas Carol, illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A. & F. Pears, 1912.

___. A Christmas Carol, illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

___. Christmas Stories, illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1976.

Patten, Robert L. "Dickens Time and Again." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 163-196.

Created 22 September 2015

Last modified 6 April 2020