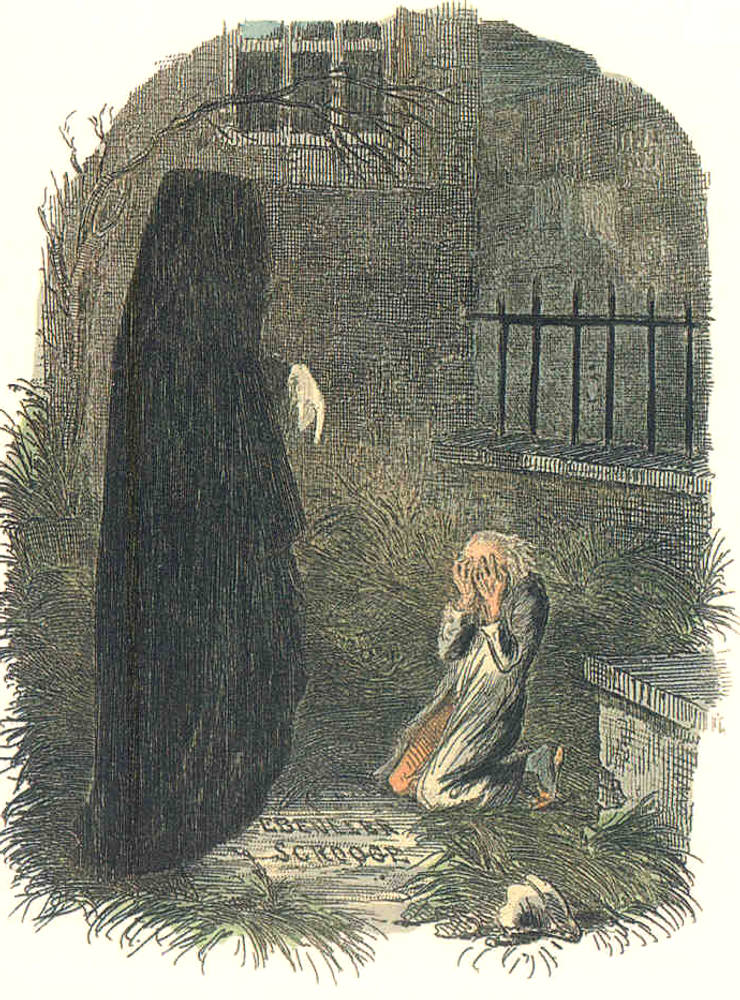

"Scrooge crept towards it, trembling as he went [See page 91" — C. E. Brock's thirteenth illustration for "A Christmas Carol" (1905) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated: "A worthy place!"

A churchyard. Here, then, the wretched man whose name he had now to learn, lay underneath the ground. It was a worthy place. Walled in by houses; overrun by grass and weeds, the growth of vegetation's death, not life; choked up with too much burying; fat with repleted appetite. A worthy place!

The Spirit stood among the graves, and pointed down to One. He advanced towards it trembling. The Phantom was exactly as it had been, but he dreaded that he saw new meaning in its solemn shape.

"Before I draw nearer to that stone to which you point," said Scrooge, "answer me one question. Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or are they shadows of things that May be, only?"

Still the Ghost pointed downward to the grave by which it stood. [Stave Four, "The Last of the Spirits," 91]

Commentary

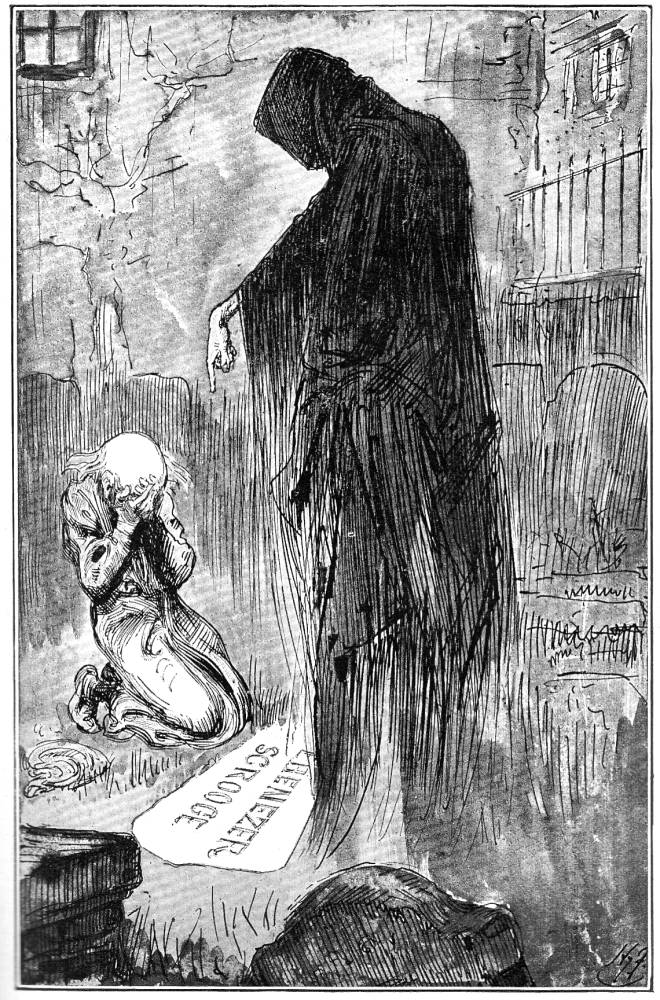

E. C. Brock had several possible models from which to work in depicting Scrooge's confrontation with his own grave, an experience that completes his spiritual and philosophical renewal. The turn-of-the-century illustrator may well have seen the churchyard scene which John Leech realised in the original edition, and he might also have seen the cover of C. Z. Barnett's dramatic adaptation in the Dicks' Standard Plays series (see below). Brock would not have had access to similar illustrations by the American Diamond Edition illustrator Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1868), the impressionistic Harry Furniss (1910), and the late Victorian or early modern illustrator Arthur Rackham (1915) — see below. Quite possibly Brock's realistic and modelled interpretation influenced that of Household Edition illustrator Charles Green's black-and-white lithograph Scrooge and the Third Spirit — "Still the Ghost pointed downward to the grave by which it stood. Scrooge crept towards it, trembling as he went: and following the finger, read upon the stone of the neglected grave his own name, EBENEZER SCROOGE" (composed in the 1890s, but not published until 1912 — see below). The common constituents of these compositions the artists have derived from both Leech's engraving and Dickens's powerful description: the graves, the overgrown cemetery, Scrooge in his nightcap (reminding the reader that this is not yet reality, but still a dream), and the shrouded spirit pointing inexorably downward. However, the orientation of the plate, background details, and the juxtapositions of the two figures vary from one rendering to another. Brock's interpretation adds the dimension of colour, not seen since the hand-tinted 1843 plate.

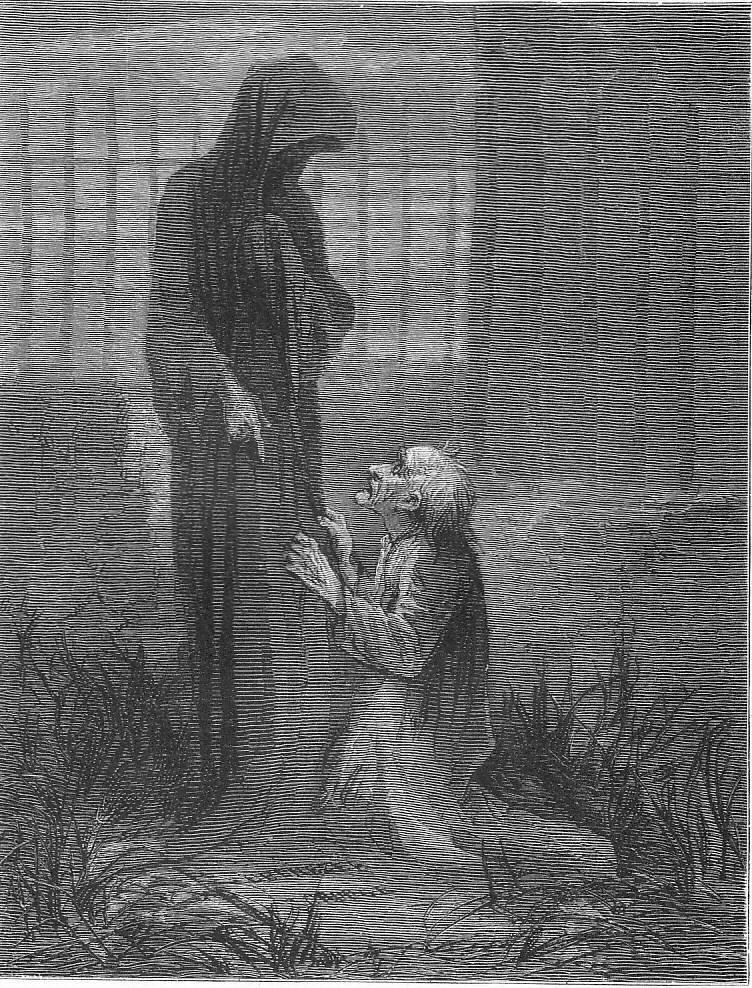

The model that Leech provided later illustrators in the 1843 first edition of the novella is even today exceptionally well known — indeed, after Oliver's Asking for More by George Cruikshank, it may well be one of the best-known illustrations from the Victorian period. In later editions, a number of illustrators have included such a scene, notably Eytinge's, focussing on Scrooge's terror, In the churchyard (see below). However, British artists Green and Brock simply may not have had access to a volume published across the Atlantic; Brock is likely to have been responding directly to Leech's graveyard scene.

The particularity with which Leech had realised the churchyard scene suggests that he may have used a definite London locale as the basis for his highly atmospheric his setting; according to Gwen Major (1932, cited by Hearn) the city burial-ground he had in mind was that of All Hallows Staining, Star Alley, off Mark Lane, in London's Langborn Ward. Whereas some illustrators have adopted a generalised backdrop, suggesting no particular locale, Brock like Leech in the detailed description of the setting seems to be reflecting an intimate knowledge of the geographical setting of the climactic scene of the dream-vision. The specificity in each case is thoroughly convincing, and the verisimilitude of Brock's plate is enhanced by his natural modelling of the figures and the perspective applied to the churchyard, which has greater depth of field than Leech's.

What distinguishes Brock's illustration from Leech's is his use of much brighter colours, which suggest that this in not a nocturnal scene, the scale and placement of the illustration (full-page, not integrated with the text), and chiefly that Scrooge has just arrived at the grave. The dreamer has already begun to plead with the ominous guide at the moment realised. In Brock's version, Scrooge, in a green silk dressing-gown rather than merely a night-gown (and therefore not revealing a bare leg as in Leech's 1843 hand-tinted engraving), does not get down among the graves as he entreats his guide and, by implication, and the reader for forgiveness and an altered conclusion. Although Brock has included marble monuments, headstones, and the wall of the church in the background to make clear the setting, this churchyard does not seem specifically urban because the illustrator has not included buildings on the other side of the area railing (in the upper right section of the Leech engraving).

The leafless tree in Leech's illustration frames the spirit guide and implies a winter setting, and an absence of both life and hope. Brock has not positioned in it in such a way that it acquires those additional meanings in this brightly-coloured lithograph. The figure beneath the shroud is more anatomically human (its arm holding up the edge of the shroud to its neck an indication of a real body beneath the covering), and Brock does not obscure Scrooge's face by having him grasp it in his hands. Scrooge, therefore, does not seem to be in the throes of despair as Leech suggests in his engraving. Finally, whereas Leech has positioned the lettering on the grave-marker so that it is legible to the reader at once, Brock has oriented the lettering so that Scrooge can read it at once — although the rest of the writing on the stone, so that the artist has not clarified the date of his death and perhaps his circumstances, leaving the reader to speculate as to how far into the imagined future Dickens has transported Scrooge. Whereas Leech makes Christmas-yet-to-Come and Christmas Present, the dominant figures in his depictions of these visitors, here Brock has placed the presiding Spirit in the right foreground and Scrooge somewhat back, so that the implied movement is from the rear towards the reader and the grave. Brock has also re-conceived Leech's Scrooge, who in this later interpretation is prostrate and diminutive. Leech's dreamer is no longer wearing his protective nightcap, but looks bald, vulnerable, pathetic. In contrast, Brock's Scrooge remains a well-dressed capitalist incongruously overbalanced as he leans forward, pleading with the implacable spirit above the grave-marker.

Relevant Illustrations from various editions, 1843-1915

Left: John Leech's atmospheric interpretation of the churchyard scene, The Last of the Spirits — The Pointing Finger (1843). Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior, depicts much the same scene but, unlike Brock, focusses upon the black-shrouded figure rather than the context of the pointing finger, a burial ground, in In the Churchyard, in the 1868 single-volume edition.

Left: A work that Brock might have influenced, Furniss's The Last of the Spirits (1910). Right: The evocative and dramatic cover of theC. Z. Barnett adaptation in Dicks' Standard Plays.

Above: Arthur Rackham's headpiece showing the scene in the forthcoming part of the novella, Heading to Stave Four (1915).

Above: Charles Green's full-page rendering of the scene may have been Brock's direct inspiration as Scrooge appears in a dressing-gown in Scrooge and the Third Spirit (1912).

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books.Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books, illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_____. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by C. E. [Charles Edmund] Brock. London: J. M. Dent, 1905; New York: Dutton, rpt., 1963.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A. & F. Pears, 1912.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The A nnotated Dickens. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1976.

Patten, Robert L. "Dickens Time and Again." Dickens Studies Annual 2 (1972): 163-196.

Created 23 September 2015

Last modified 31 May 2020