"Crusoe and Friday" for Daniel Defoe's "Adventures of Robinson Crusoe" (1863-64) (original) (raw)

The Passage Illustrated: Another Memorable Moment

The poor savage who fled, but had stopped, though he saw both his enemies fallen and killed, as he thought, yet was so frightened with the fire and noise of my piece that he stood stock still, and neither came forward nor went backward, though he seemed rather inclined still to fly than to come on. I hallooed again to him, and made signs to come forward, which he easily understood, and came a little way; then stopped again, and then a little farther, and stopped again; and I could then perceive that he stood trembling, as if he had been taken prisoner, and had just been to be killed, as his two enemies were. I beckoned to him again to come to me, and gave him all the signs of encouragement that I could think of; and he came nearer and nearer, kneeling down every ten or twelve steps, in token of acknowledgment for saving his life. I smiled at him, and looked pleasantly, and beckoned to him to come still nearer; at length he came close to me; and then he kneeled down again, kissed the ground, and laid his head upon the ground, and taking me by the foot, set my foot upon his head; this, it seems, was in token of swearing to be my slave for ever. I took him up and made much of him, and encouraged him all I could. But there was more work to do yet; for I perceived the savage whom I had knocked down was not killed, but stunned with the blow, and began to come to himself: so I pointed to him, and showed him the savage, that he was not dead; upon this he spoke some words to me, and though I could not understand them, yet I thought they were pleasant to hear; for they were the first sound of a man's voice that I had heard, my own excepted, for above twenty-five years. [Chapter XIV, "A Dream Realised," p. 137]

Another Iconic Moment: Crusoe meets Friday

Thomas emphasizes psychological realism, avoiding many of the details George Cruikshank had included in the first nineteenth-century illustration of this famous scene ln English literature. Here Crusoe quietly welcomes the young, scantily-clad youth whose live he has just saved. The cannibal whom Crusoe has just felled (left rear) is attempting to rise, and another lies dead on the ground just behind Crusoe, his leg and arm barely visible. Thomas lets nothing detract from our assessment of Crusoe's benign expression and the gestures and poses of man and master.

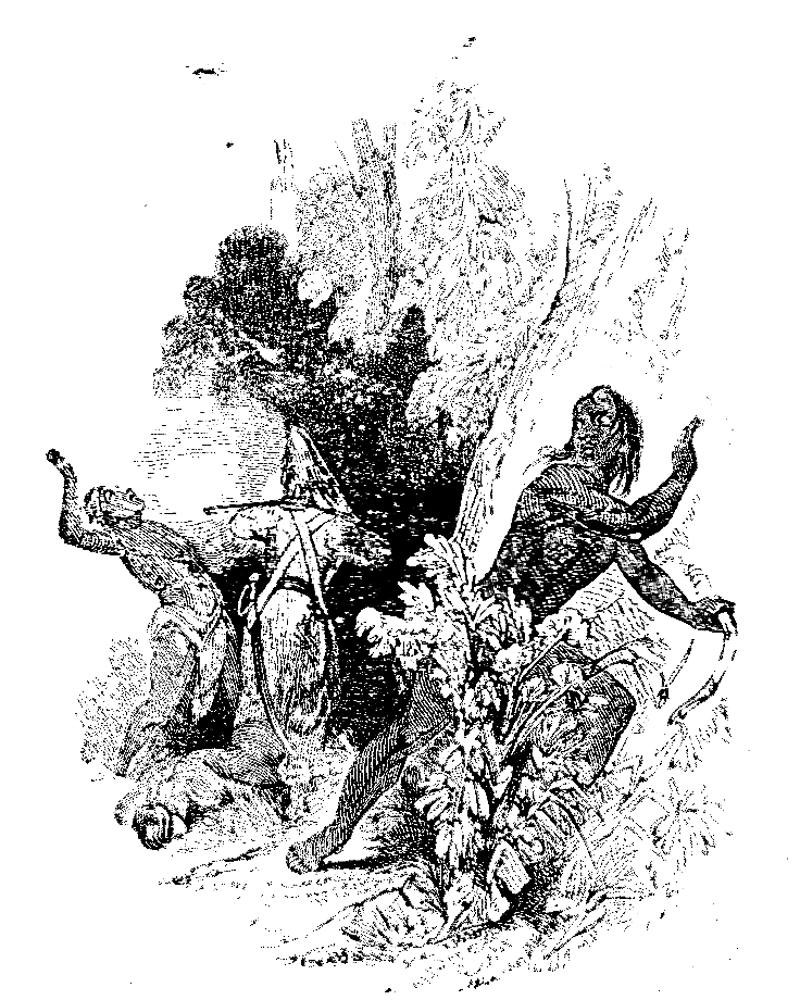

Despite the fact that the rifle he carries is conspicuous, Thomas's Crusoe, like Cruikshank's, is essentially benign: a combination of a hairy John the Baptist and Christ as the Good Shepherd and Prince of Peace. And, Cruikshank’s illustration, so here "Crusoe extends his hand, palm upward, in a non-threatening and traditional gesture of succour" (Blewett, p. 35). Whereas Cruikshank had included all the textual elements that the reader would expect to find in a faithful realisation (the two dead savages, the stream, and well in the background the other cannibals, cavorting around a bonfire), Thomas, like Phiz in his frontispiece, has brought the figures well forward. However, unlike Phiz Thomas adds no jarring note by threatening the rescuer. In the 1864 short narrative-pictorial Phiz depicts a Crusoe so intent upon allaying the fears of the naked and bound supplicant that he has turned his back on the fierce-looking aboriginal warrior (clearly not a Negro) who is clutching a tomahawk. Like Cruikshank, Thomas has minimised such contextual elements in order to focus on the meeting of the European man gone back to nature (as implied by his goatskin garb) and the natural man, naked but for a loincloth, being introduced to civilisation. "Though the tropical vegetation introduces a more or less realistic note rarely struck in the eighteenth-century illustration, the scene is essentially symbolic, a survival of a central icon in the eighteenth-century imagination, and a powerful image of the meeting of two worlds" (Blewett,p. 35).

Once again, Thomas, the master of psychological realism, has clearly identified this as his work by the prominently placed signature. "GHT" (lower left) indicates that this key moment in the narrative-pictorial sequence is the work of the celebrated English painter, woodblock engraver, and illustrator. Although he specialised in illustrating current affairs such as the Crimean War, Thomas provided illustrations for a number of popular novels, including Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1853), Trollope's Last Chronicle of Barset (1867), and Thomas More's oriental romance Lalla Rookh (1868). His interests in the tropics and in biography combine brilliantly in The Life and Adventures of Dr. Livingston: in the interior of South Africa (1868). Thomas underscores the energy of Defoe's description by means of vigorous cross-hatching at the feet of Crusoe and Friday, the texture of Friday's skin (accomplished with a mechanical ruler), and the goatskin suit's strong verticals. The master-illustrator subordinates all elements within the composition in order to direct the eye of the reader to the apex of the pyramid, Crusoe's noble head. Strategically, the illustrator merely hints at Friday's expression, leaving each viewer to complete that important element as he or she sees fit.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Related Scenes from Stothard (1790), Phiz (1864), the 1818 Children's Book, Cruikshank (1831), and Gilbert (1867?)

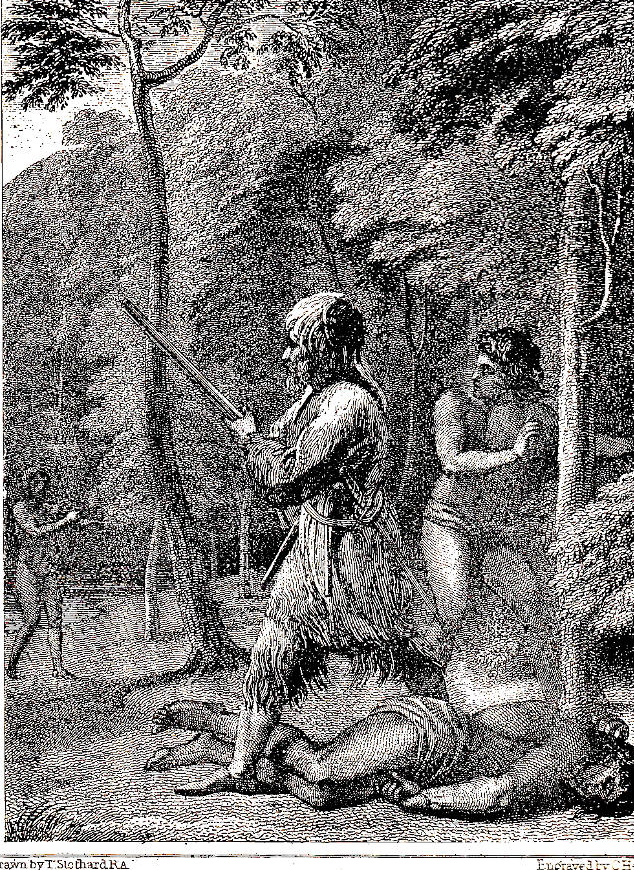

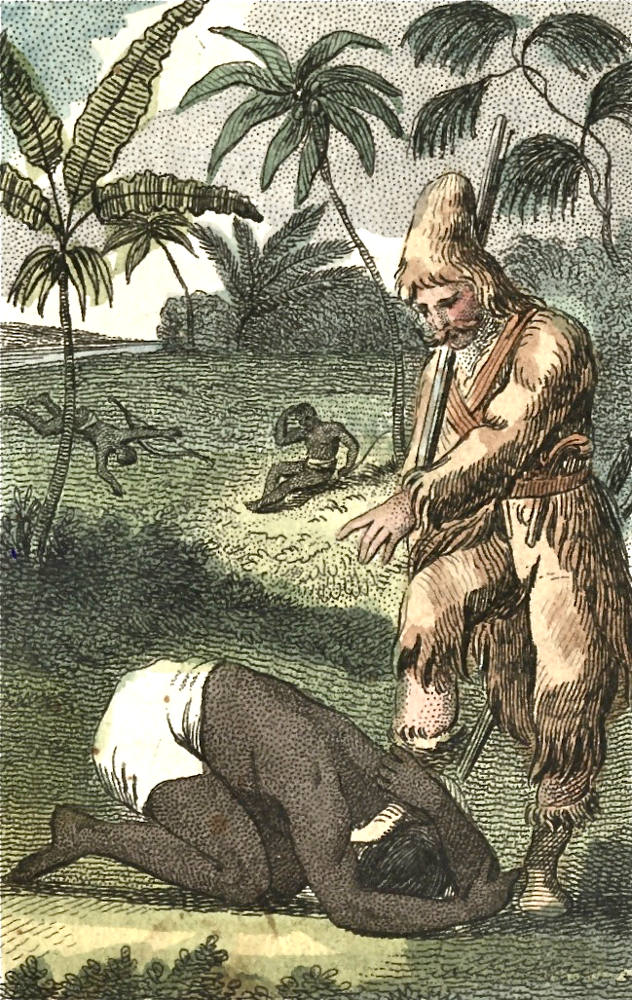

Left: Stothard's 1790 realisation of the rescue scene, an illustration of which Cruikshank was probably aware, Robinson Crusoe first sees and rescues his man Friday (copper-plate engraving, [Chapter XIV, "A Dream Realised"). Centre: Phiz's steel-engraved frontispiece, with the surviving pursuer about to attack the unwitting Crusoe, Robinson Crusoe rescues Friday (1864). Right: Colourful realisation of the same scene, with a decidedly subservient and Negroid Friday: Friday's first interview with Robinson Crusoe. (1818).

Left: An elegant oval vignette of Crusoe in "island dress" on the shore, I was much surprized at the print of a man's foot on the shore (1820). Right: Cruikshank's atmospheric realisation of the same scene, Crusoe having just rescued Friday (1831). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Blewett, David. "Robinson Crusoe, Friday, and the Noble Savage: The Illustration of the Rescue of Friday Scene in the Eighteenth Century." Man and Nature, Vol. 5 (1986), 29–49. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/man/1986-v5-man0238/1011850ar.pdf

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by himself. With upwards of One Hundred Illustrations. London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin, 1863-64.

Last modified 14 March 2018