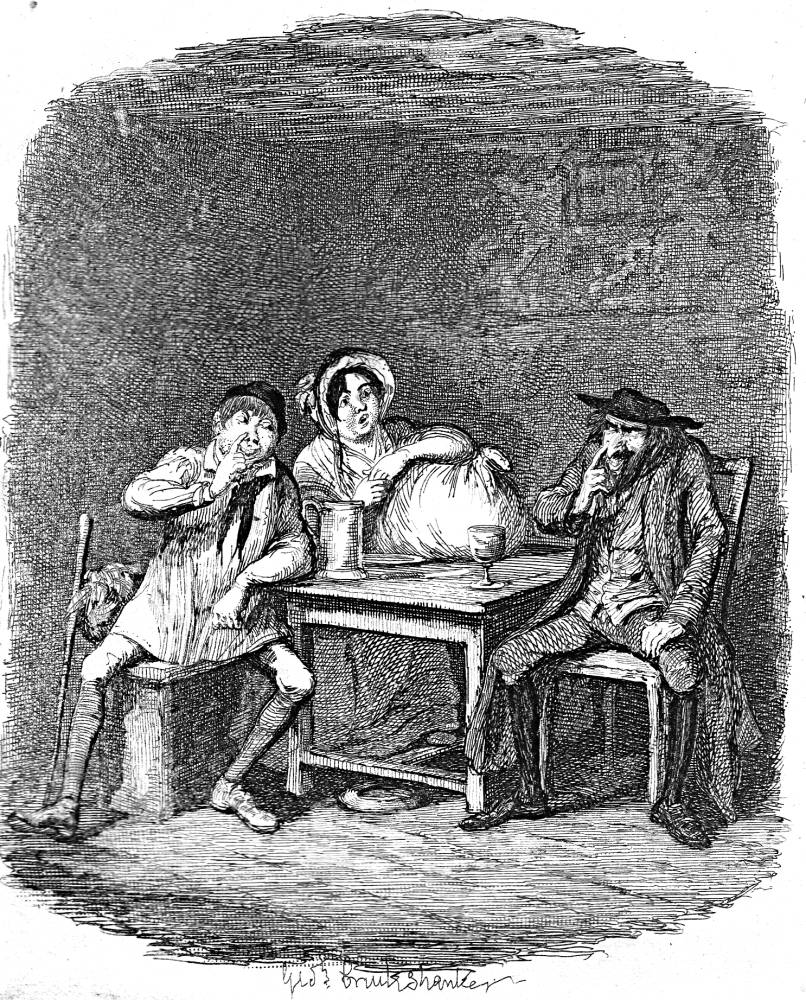

"The Arbour at Kilburn," seventh George Cruikshank illustration for Ainsworth's "Rookwood. A Romance" (1834, il. 1836) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

The present straggling suburb at the north-west of the metropolis, knownas Kilburn, had scarcely been called into existence a century ago, and an ancient hostel, with a few detached farmhouses, were the sole habitations to be found in the present populous vicinage. The place of refreshment for the ruralizing cockney of 1737 was a substantial-looking tenement of the good old stamp, with great bay windows, and a balcony in front, bearing as its ensign the jovial visage of the lusty knight, Jack Falstaff. Shaded by a spreading elm, a circular bench embraced the aged trunk of the tree, sufficiently tempting, no doubt, to incline the wanderer on those dusty ways to "rest and be thankful," and to cry encore to a frothing tankard of the best ale to be obtained within thechimes of Bow bells.

Upon a table, green as the privet and holly that formed the walls of the bower in which it was placed, stood a great china bowl, one of thoseleviathan memorials of bygone wassailry which we may sometimes espy— reversed in token of its desuetude— perched on the top of an oldjapanned closet, but seldom, if ever, encountered in its proper positionat the genial board. All the appliances of festivity were at hand. Pipes and rummers strewed the board. Perfume, subtle, yet mellow, as of pine and lime, exhaled from out the bowl, and, mingling with the scent of a neighboring bed of mignonette and the subdued odor of the Indian weed, formed altogether as delectable an atmosphere of sweets as one could wish to inhale on a melting August afternoon. So, at least, thought the inmates of the arbor; nor did they by any means confine themselves to the gratification of a single sense. The ambrosial contents of the china bowl proved as delicious to the taste as its bouquet was grateful to the smell; while the eyesight was soothed by reposing on the smooth sward of a bowling-green spread out immediately before it, or in dwelling upon gently undulating meads, terminating, at about a mile's distance, in the woody, spire-crowned heights of Hampstead.

At the left of the table was seated, or rather lounged, a slender, elegant-looking young man, with dark, languid eyes, sallow complexion, and features wearing that peculiarly pensive expression often communicated by dissipation; an expression which, we regret to say, is sometimes found more pleasing than it ought to be in the eyes of the gentle sex. Habited in a light summer riding-dress, fashioned according to the taste of the time, of plain and unpretending material, and rather under than overdressed, he had, perhaps, on that very account, perfectly the air of a gentleman. There was, altogether, an absence of pretension about him, which, combined with great apparent self-possession, contrasted very forcibly with the vulgar assurance of his showy companions. The figure of the youth was slight, even to fragility, giving little outward manifestation of the vigor of frame he in reality possessed. This spark was a no less distinguished personage than Tom King, a noted high-tobygloak of his time, who obtained, from his appearance and address, the _sobriquet_of the "Gentleman Highwayman."— Book Four, "The Ride to York," Chapter 1, "The Rendezvous at Kilburn," p. 244-245.

Commentary

The scene appears not against the textual description of the "bower," but opposite the drinking songs "Pledge of the Highwayman" and "The Four Cautions," both of which are entirely digressive in terms of the Rookwood inheritance plot. Indeed, from now on in both the George Cruikshank and the John Gilbertprogrammes of illustration, the dashing, luxuriantly-whiskered Dick Turpin usurps the central role in the story, nudging Lady Rookwood, Sir Luke Rookwood, and Eleanor Mowbray, and the Yorkshire Gypsies well to the margins. Only in his final illustration, Death of Lady Rookwood does Cruikshank take up the threads of the main plot. Undoubtedly both illustrators found the gallant highwayman far more engaging and visually interesting than the thinly-drawn characters from the interminable inheritance plot.

We pick up the narrative in north London, wither Dick Turpin and his associates, including Jerry Juniper and Zoroaster from the gypsy encampment, have fled after the terrible events subsequent to the marriage of Luke Rookwood and Sybil, events which are narrated at length by the quartet. The Cruikshank illustration seems to be related to this moment in the comic banter of the four imbibers which sets up Turpin's daring "Ride to York":

"Ha, ha!" laughed Tom. "And now, Dick, to change the subject. You are off, I understand, to Yorkshire to-night. 'Pon my soul, you are a wonderful fellow — an alibi personified! — here and everywhere at the same time — no wonder you are called the flying highwayman. To-day in town — to-morrow at York — the day after at Chester. The devil only knows where you will pitch your quarters a week hence. There are rumors of you in all counties at the same moment. This man swears you robbed him at Hounslow; that on Salisbury Plain; while another avers you monopolize Cheshire and Yorkshire, and that it isn't safe even to hunt without pops in your pocket. I heard some devilish good stories of you at D'Osyndar's t'other day; the fellow who told them to me little thought I was a brother blade." — Book IV, "The Ride to York," Chapter 2, "Tom King," p. 256 [1878 edition].

Since the moment flagged by the previous illustration, The Bridal, much has transpired: at the close of Book III, "The Gipsy," Dick Turpin has escaped from Lady Rookwood's minions, Titus Tyrconnel and attorney Coates, carrying both the lawyer's bill of exchange and the marriage certificate which establishes Luke's legitimacy. Sybil is dead, killed by her own grandmother in fulfilment of the Rookwood curse, and Luke is free to marry heiress Eleanor Mowbray, if he can outwit Lady Rookwood. Sure that the young heir will succeed if he has the highwayman's support, Turpin is determined to ride back to Yorkshire. Mrs. Mowbray, meanwhile, is determined to see her daughter marry Lady Rookwood's son, Ranulph, and has the support of Barbara Lovel, who has apparently turned against Luke.

The composition includes two of the figures from the Gypsy encampment, but, since Cruikshank had not depicted either Zoroaster or Jerry Juniper in the marriage ceremony, he was free to show them show them as the drinking scene required. The quartet are engaged in an anacreontic chorus led by the smartly dressed highwayman, distinguished by his whip, as he raises his glass (right). Following the logic of the text, right of centre is Tom King (who sings "Pledge of the Highwayman"), then "next to King" Jerry Juniper (who, dressed in "the finest linen and hose," and bearing a silver-hilted sword, has adopted the alias "Count Albert Conyers"), and Zoroaster, left of centre, with a long-stemmed pipe. In this new, fashionable guise, Jerry (raising his glass, left) has just concluded the first-person narrative of what befell the principals after the marriage ceremony in the crypt: he has accounted for the fates of Luke, Eleanor, the Jesuit priest (Father Checkley), Alan Rookwood (who has now dropped the alias "Peter Bradley), and introduced Ranulph Rookwood as a rival to Luke, and Major Mowbray as the lad's stout supporter in the battle between the gypsies and the local farmers. In the fray, Turpin's companions Rust and Wilder have been slain, and Turpin himself temporarily taken prisoner after the gypsies have abandoned the field of battle. The wassail bowl seems rather far removed from the chief celebrant, the jolly Dick Turpin, and such distinguishing features as Jerry's powdered peruke and Tom's toothpick and snuff-box are absent, but Zoroaster is readily identifiable by his eye-patch and the damage that his face had sustained in the recent fray: "Not a feature was in its place; his swollen lip trespassed upon the precincts of his nose; his nose trod hard upon his cheek" (248). Ironically, then, only in the description of this most minor of characters has Ainsworth aided his illustrator in particularizing the anacreontic quartet.

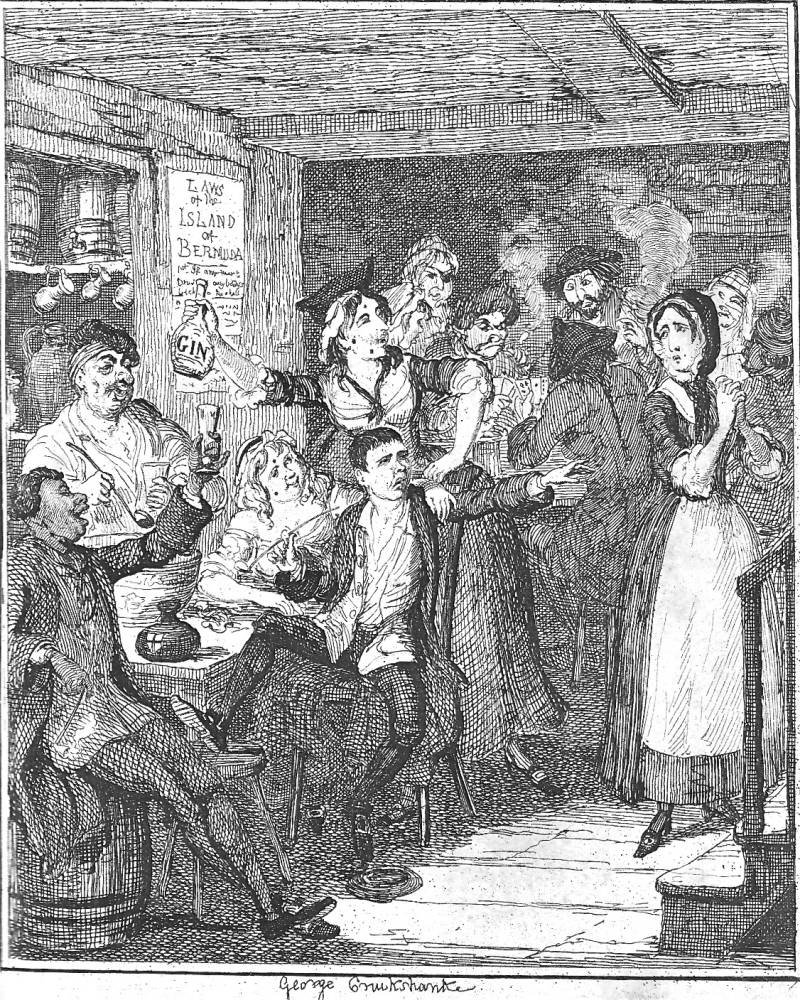

Such tavern scenes are a Cruikshank speciality, but are more effective when, as in the case Oliver Twist, the writer has provided the illustrator with detailed descriptions of the characters and the scene, as in Charles Dickens's The Jew & Morris Both begin to understand each other (November 1838) and Harrison Ainsworth's Jack Sheppard gets drunk, and orders his Mother off (May 1839). If the scene involves some significant development in the plot or revelation of character, Cruikshank seems better able to rise to the task.

Relevant Illustrations of Drinking Scenes

Left: George Cruikshank's The Jew and Morris Both begin to understand each other (Part 19 of Oliver Twist, November 1838). Centre: George Cruikshank's Jack Sheppard gets drunk, and orders his Mother off (May 1839). Right: George Cruikshank's communal drinking scene in Dickens's Sketches by Boz, The Gin Shop (1836). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Related Materials

- The illustrations of Sir John Gilbert, R. A. for Rookwood, A Romance (1878)

- The illustrations of George Cruikshank for Jack Sheppard: A Romance (1839)

- William Harrison Ainsworth (1805-1882) — King of the Historical Potboiler: A Brief Biography

- A Chronology of William Harrison Ainsworth (1805-1882)

- An Introduction to Ainsworth's Rookwood, A Romance (1836)

- An Introduction to Ainsworth's Jack Sheppard. A Romance (1839)

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. Jack Sheppard. A Romance. With 28 illustrations by George Cruikshank. In three volumes. London: Richard Bentley, 1839.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. Accessed 1 November 2016. https://ainsworthandfriends.wordpress.com/2013/01/16/william-harrison-ainsworth-the-life-and-adventures-of-the-lancashire-novelist/

Dickens, Charles. Pilgrim ed. of the Letters of Charles Dickens, Vol. 5 (1847-1849). Ed. Graham Storey and Katherine Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1981.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

Muir, Percy. "Two Colossi — Thomas Bewick and George Cruikshank." Victorian Illustrated Books. London: B. T. Batsford, 1971. Pp. 25-58.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Sutherland, John. "Rookwood" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. Pp. 544-545.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Last modified 20 February 2017