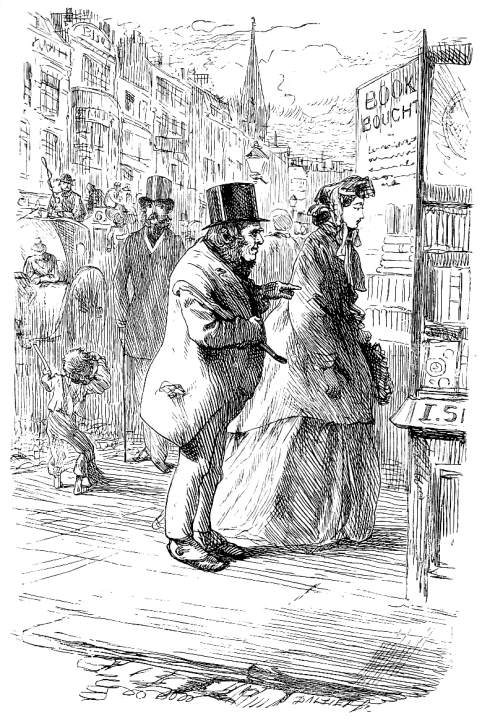

"Mr. Boffin engages Mr. Wegg" — Page 76; Felix O. C. Darley's first illustration for "Our Mutual Friend" (1872) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated: Boffin Makes Wegg a Generous Offer

"Now, Wegg," said Mr.Boffin, hugging his stick closer, "I want to make a sort of offer to you. Do you remember when you first see me?"

The wooden Wegg looked at him with a meditative eye, and also with a softened air as descrying possibility of profit. "Let me think. I ain't quite sure, and yet I generally take a powerful sight of notice, too. Was it on a Monday morning, when the butcher-boy had been to our house for orders, and bought a ballad of me, which, being unacquainted with the tune, I run it over to him?"

"Right, Wegg, right! But he bought more than one."

"Yes, to be sure, sir; he bought several; and wishing to lay out his money to the best, he took my opinion to guide his choice, and we went over the collection together. To be sure we did. Here was him as it might be, and here was myself as it might be, and there was you, Mr. Boffin, as you identically are, with your self-same stick under your very same arm, and your very same back towards us. To — be — sure!" added Mr. Wegg, looking a little round Mr. Boffin, to take him in the rear, and identify this last extraordinary coincidence, "your wery self-same back!"

"What do you think I was doing, Wegg?"

"I should judge, sir, that you might be glancing your eye down the street."

"No, Wegg. I was a listening."

"Was you, indeed?" said Mr. Wegg, dubiously.

"Not in a dishonorable way, Wegg, because you was singing to the butcher; and you wouldn't sing secrets to a butcher in the street, you know."

"It never happened that I did so yet, to the best of my remembrance,"said Mr. Wegg, cautiously.

"But I might do it. A man can't say what he might wish to do some day or another." (This, not to release any little advantage he might derive from Mr. Boffin's avowal.)

"Well,"repeated Boffin, "I was a listening to you and to him. And what do you — you haven't got another stool, have you? I'm rather thick in my breath."

"I haven't got another, but you're welcome to this,"said Wegg, resigning it. "It's a treat to me to stand."

"Lard!" exclaimed Mr. Boffin, in a tone of great enjoyment, as he settled himself down, still nursing his stick like a baby, "it's a pleasant place, this! And then to be shut in on each side, with these ballads, like so many book-leaf blinkers! Why, it's delightful!"

"If I am not mistaken, sir,"Mr. Wegg delicately hinted, resting a hand on his stall, and bending over the discursive Boffin, "you alluded to some offer or another that was in your mind?"

"I'm coming to it! All right. I'm coming to it! I was going to say that when I listened that morning, I listened with hadmiration amounting to haw. I thought to myself, 'Here's a man with a wooden leg — a literary man with'" —

"N — not exactly so, sir,"said Mr. Wegg.

"Why, you know every one of these songs by name and by tune, and if you want to read or to sing any one on 'em off straight, you've only to whip on your spectacles and do it!"cried Mr. Boffin. "I see you at it!"

"Well, sir,"returned Mr. Wegg, with a conscious inclination of the head; "we'll say literary, then."

"'A literary man_with_a wooden leg — and all Print is open to him!' That's what I thought to myself, that morning," pursued Mr. Boffin, leaning forward to describe, uncramped by the clothes-horse, as large an arc as his right arm could make; '"'all Print is open to him!' And it is, ain't it?"

"Why, truly, sir,"Mr. Wegg admitted, with modesty; "I believe you couldn't show me the piece of English print, that I wouldn't be equal to collaring and throwing."

"On the spot?"said Mr. Boffin.

"On the spot."

"I know'd it! Then consider this. Here am I, a man without a wooden leg, and yet all print is shut to me."

"Indeed, sir?"Mr. Wegg returned with increasing self-complacency. "Education neglected?"

"Neg — lected!"repeated Boffin, with emphasis. "That ain't no word for it. I don't mean to say but what if you showed me a B, I could so far give you change for it, as to answer Boffin."

"Come, come, sir,"said Mr. Wegg, throwing in a little encouragement, "that's something, too."

"It's something," answered Mr. Boffin, "but I'll take my oath it ain't much."

"Perhaps it's not as much as could be wished by an inquiring mind, sir," Mr. Wegg admitted.

"Now, look here. I'm retired from business. Me and Mrs. Boffin — Henerietty Boffin — which her father's name was Henery, and her mother's name was Hetty, and so you get it — we live on a compittance, under the will of a diseased governor."

"Gentleman dead, sir?"

"Man alive, don't I tell you? A diseased governor? Now, it's too late for me to begin shovelling and sifting at alphabeds and grammar-books. I'm getting to be a old bird, and I want to take it easy. But I want some reading — some fine bold reading, some splendid book in a gorging Lord-Mayor's-Show of wollumes" (probably meaning gorgeous, but misled by association of ideas); "as'll reach right down your pint of view, and take time to go by you. How can I get that reading, Wegg? By,"tapping him on the breast with the head of his thick stick,"paying a man truly qualified to do it, so much an hour (say twopence) to come and do it."

"Hem! Flattered, sir, I am sure,"said Wegg, beginning to regard himself in quite a new light. "Hew! This is the offer you mentioned, sir?"

"Yes. Do you like it?"

"I am considering of it, Mr.Boffin."

"I don't," said Boffin, in a free-handed manner, "want to tie a literary man — with a wooden leg — down too tight. A halfpenny an hour shan't part us. The hours are your own to choose, after you've done for the day with your house here. I live over Maiden-Lane way — out Holloway direction — and you've only got to go East-and-by-North when you've finished here, and you're there. Twopence halfpenny an hour," said Boffin, taking a piece of chalk from his pocket and getting off the stool to work the sum on the top of it in his own way; "two long'uns and a short'un — twopence halfpenny; two short'uns is a long'un and two two long'uns is four long'uns — making five long'uns; six nights a week at five long'uns a night," scoring them all down separately, "and you mount up to thirty long'uns. A round'un! Half a crown!"

Pointing to this result as a large and satisfactory one, Mr. Boffin smeared it out with his moistened glove, and sat down on the remains.

"Half a crown," said Wegg, meditating. "Yes. (It ain't much, sir.) Half a crown."

"Per week, you know."

"Per week. Yes. As to the amount of strain upon the intellect now. Was you thinking at all of poetry?"Mr. Wegg inquired, musing. — Vol. 1, Ch. 5, "Boffin's Bower," pp. 76-79.

Commentary: Noddy Boffin, illiterate but rich, hires a reader.

One of the most memorable meetings in nineteenth-century British literature is involved in Noddy Boffin's hiring the duplicitous one-legged ballad-monger, Silas Wegg, to read him Gibbon's The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire. Working in 1866 on three frontispieces for the May 1864-November 1865 novel, Darley had at hand the models of Boffin and Wegg provided in the monthly parts by Dickens's new illustrator Marcus Stone, working in the new, realistic mode of the 1860s. However, since neither character in this initial frontispiece much resembles his counterpart in the Stone illustrations, Darley apparently felt uncomfortable with the new style and elected to take an approach more consistent with the earlier, caricatural style as exemplified by the work of Hablot Knight Browneand George Cruikshank. Darley has, moreover, reduced the size of Wegg's stall and reduced considerably the space occupied by backgroundbuildings in his revision of Stone's Bibliomania of the Golden Dustman (April 1865) in order to focus on the character of Wegg, under his enormous umbrella, as described in the following passage at the opening of the fifth chapter:

Over against a London house, a corner house not far from Cavendish Square, a man with a wooden leg had sat for some years, with his remaining foot in a basket in cold weather, picking up a living on this wise: — Every morning at eight o'clock, he stumped to the corner, carrying a chair, a clothes-horse, a pair of trestles, a board, a basket, and an umbrella, all strapped together. Separating these, the board and trestles became a counter, the basket supplied the few small lots of fruit and sweets that he offered for sale upon it and became a foot-warmer, the unfolded clothes-horse displayed a choice collection of halfpenny ballads and became a screen, and the stool planted within it became his post for the rest of the day. All weathers saw the man at the post. This is to be accepted in a double sense, for he contrived a back to his wooden stool, by placing it against the lamp-post. When the weather was wet, he put up his umbrella over his stock in trade, not over himself; when the weather was dry, he furled that faded article, tied it round with a piece of yarn, and laid it cross-wise under the trestles: where it looked like an unwholesomely-forced lettuce that had lost in color and crispness what it had gained in size. [69]

In contrast to the subtlety of Darley's engraving, the other illustrators of the period utlised the bold lines of the composite wood-block engraving, with particularly dramatic effect in the Household Edition half- and whole-page illustrations by social realist James Mahoney. As both J. A. Hammerton and Frederic G. Kitton have noted, Marcus Stone, the original part-publication illustrator, worked closely with Dickens, so that the resulting illustrations bear the stamp of authorial intention, influencing such later illustrators as Harry Furniss. Conversations with and detailed notes from the novelist gave young Stone direct access to what he himself termed Dickens's "pictorialism" (Kitton 197), that is, an innate sense of what in in a text will be most suitable as an illustration. Although Darley did not have these opportunities for artistic collaboration with Dickens, he was generally an outstanding "'character' draughtsman" (Kitton 223) with the knack of placing complementary characters together in an interesting situation as described in the narrative. Such is the case with his dual portrait of the genial dustman, the millionaire of garbage, and his alter-ego, the envious malcontent and purveyor of shoddy goods, Silas Wegg.

Both Darley and John Gilbert, working on the Hurd and Houghton edition frontispieces just the year after the book's publication in England, at least had the opportunity to study Marcus Stone's work, but developed different scenes and developed their own interpretations of the characters. In the case of Boffin, Darley has produced a heavy-set man of advanced middle age trying to dress like a bourgeois, but not quite comfortable in his respectable clothing, over which he wears a serviceable but not particularly fashionable jacket (a "pea overcoat"), revealing the tails of his frock-coat. Darley has incorporated the broad-brimmed hat and gaiters of Dickens's text, but shows only Boffin's profile. He is not as obtuse as the Boffin produced the following year by Darley's fellow American, Sol Eytinge, Jr. The artist has lavished considerably more attention on the ballad-monger, detailing his wares and conspicuously showing his salient feature, a wooden leg, under his table. Oddly enough, Darley has Wegg sitting on a chair rather than a stool, and makes his face more pliable and less stoney than Dickens suggests. Both characters in the 1866 frontispiece are more engaging, however, than their counterparts in Mahoney's wood-engravings of 1864-65.

Boffin and Wegg in the original, Diamond, Household, and Charles Dickens Library Editions

Left: Marcus Stone's April 1865 serial illustration of Boffin's looking for a volume entitled Tales of Misers at a bookstall, Bibliomania of the Golden Dustman.Centre: The same scene, updated by Harry Furniss in 1910: The Search for “Lives” of Misers. Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's interpretation of theGolden Dustman and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Boffin (1867). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

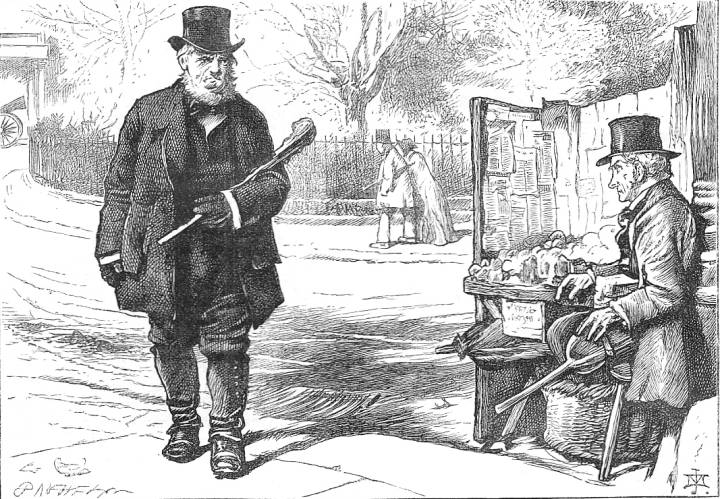

Above: James Mahoney's realistic interpretation of Boffin's meeting Wegg at his bookstall in Book One, Chapter Five, "Here you are again," repeated Mr. Wegg, musing. "And what are you now?" (Household Edition, 1875). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "The Illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Marcus Stone, Charles Collins, Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 203-228.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [40 composite wood-block engravings]. The Authentic Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. 21 vols. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901 [based on the original nineteen-month serial and the two-volume edition of 1865]. Vol. XIV.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1872. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Vol. VIII.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. 22 vols. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1875. Vol. IX.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. XV.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 21: The Other Novels." The Dickens Picture-Book. The CharlesDickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. XVII. 441-442.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. London: George Redway, 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2004.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"Our Mutual Friend — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Vann, J. Don. "Our Mutual Friend, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, May 1864—November 1865." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 74.

Created 14 November 2015

Last updated 6 August 2025