"The end of a long Journey — Felix O. C. Darley's third illustration to "Our Mutual Friend" (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

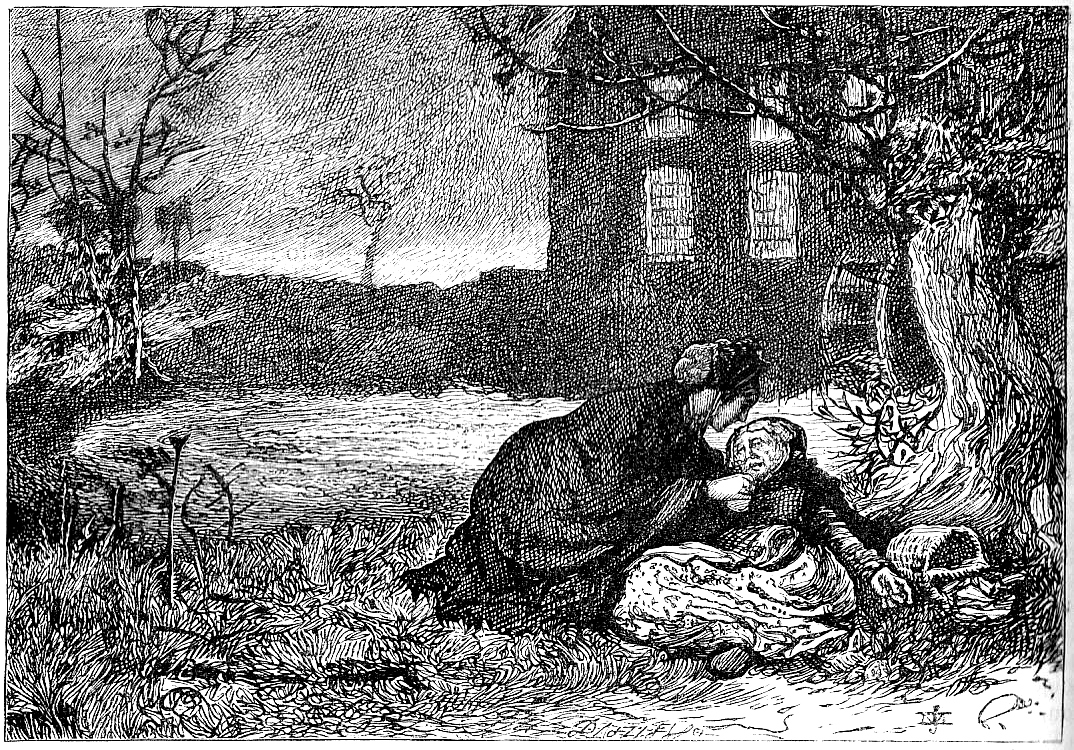

She crept among the trees to the trunk of a tree whence she could see, beyond some intervening trees and branches, the lighted windows, both in their reality and their reflection in the water. She placed her orderly little basket at her side, and sank upon the ground, supporting herself against the tree. It brought to her mind the foot of the Cross, and she committed herself to Him who died upon it. Her strength held out to enable her to arrange the letter in her breast, so as that it could be seen that she had a paper there. It had held out for this, and it departed when this was done.

"I am safe here," was her last benumbed thought. "When I am found dead at the foot of the Cross, it will be by some of my own sort; some of the working people who work among the lights yonder. I cannot see the lighted windows now, but they are there. I am thankful for all!"

The darkness gone, and a face bending down.

"It cannot be the boofer lady?"

"I don't understand what you say. Let me wet your lips again with this brandy. I have been away to fetch it. Did you think that I was long gone?"

It is as the face of a woman, shaded by a quantity of rich dark hair. It is the earnest face of a woman who is young and handsome. But all is over with me on earth, and this must be an Angel.

"Have I been long dead?" [Book Three, Ch. 8, "The end of a long Journey," III, 140.]

Commentary: Betty Higden and The Shadow of the Workhouse

It is quite likely that both Darley andSol Eytinge, Jr., the first American illustrators ofOur Mutual Friend first read the novel as a monthly serial in Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June 1864 through December 1865 — in other words, in instalments that were exactly one month later than the monthly parts issued in Great Britain (May 1864 through November 1865). American readers such as these two illustrators would have encountered the sentimental death of Betty Higden, attended by Lizzie Hexam, near the paper-mill on the upper Thames in Part 13 (June 1865), pages 101-121 in Harper's, an instalment that includesBibliomania of the Golden Dustman, The Evil Genius of the House of Boffin (both relating to the previous number, published in the New York periodical in May), and the two wood-engravings pertaining to the June instalment, The Flight, and Threepenn'orth Rum, the former two appearing in Great Britain in the April 1865 number and the latter two in the May 1865 instalment.

Thus, the thirteenth instalment, which would have contained the twelfth chapter of the third book, Darley would probably have read in June 1865, less than twelve months ahead of when he executed the four frontispieces for the Hurd and Houghton "Household Edition" initiated five years earlier by New York publisher James G. Gregory. Undoubtedly the dramatic death of Betty would have had a powerful effect on both American illustrators, but only Darley's program permitted him to realise the sentimental scene in which Betty Higden dies of a stroke in the woods rather than take refuge in the universally detested union workhouse. In fact, to forestall some well-meaning attempt to carry her corpse to such a place for burial, Betty has sewn the money to cover the cost of a decent burial into the lining of her skirt. As Ruth Richardson notes, over the course of thirty years, beginning with Oliver Twist, Dickens had presented a uniform assault on the institution of the workhouse and the act of Parliament that created it, the 1834 Poor Law, utlising editorials in Household Words as well as fictional characters:

Among the most recent of these had been the character of Betty Higden inOur Mutual Friend, who takes to the road rather than die in a workhouse. The book was the last novel Dickens completed before his death, published in parts over the period of 1864-5 — just ahead of and in parallel with the Lancet Sanitary Commission's Reports. The words the audience at the great meeting heard [Dr. Joseph] Rogers read aloud referring to the poor creeping into corners to die rather than fester and rot in workhouse wards, refer to those — young and old — who preferred to sleep out under the stars rather than enter those hateful places, and to the incomprehension which met their deaths. Dickens's creation Betty Higden addresses this incomprehension, by way of explaining the self-respect that refused to be browbeaten by the coercive humiliation of applying for help to the workhouse. [Richardson 296]

The novel, then, appeared a year before the government's official enquiry into the continuing abuses of the workhouse system vindicated Dickens's attack most pointedly delivered in the death of Betty Higden. Through her fictional sufferings, Betty helped to bring down the workhouses, which progressive parliamentarians replaced with a system of public infirmaries for the poor who were ill, and instituted the Metropolitan Asylums Board for those indigents who were insane or had infectious diseases. The new hospitals constructed in the decade following Our Mutual Friend became the basis for the National Health Service.

In contrast to the simplicity of Eytinge's wood-engraving, Darley's frontispiece presents Betty in a natural, detailed setting. She is old and gnarled in Stone's and Mahoney's final illustrations of her, but Darley intensifies her humanity in her final moments through her look of dazed confusion at the young woman whom she mistakes for an angel. In Stone, she marches determinedly away from town with the talk of the poorhouse, but in Darley she tries to sit up against the tree at whose base she has fallen. Whereas Mahoney in Lizzie Hexam very softly raised the weather-stained grey head, and lifted her as high as Heavensupplies a weir, mill-wheel, and factory as the backdrop (perhaps with the implication that her death before such a building is more fitting than in a workhouse), Darley minimizes both the dwelling (right rear) and the mill-wheel and factory (left rear) to focus on Betty and her nurse, surrounded by her bonnet, basket, and knitting by which she has been making a meagre living these past weeks. The leafless tree in the Mahoney plate may well be a Betty has striven for and achieved a "natural" death, retaining her dignity and individuality to the end. Lizzie seems relatively anonymous in the Mahoney illustration, but Darley presents her as well dressed, her hair neatly arranged, like the mill-girls of Lowell, Massachusetts, and Manchester, New Hampshire.

The American illustrators would have been well ware of the short-comings of the poorhouse as a vehicle for the relief of the old and indigent, but the Civil War, just concluded when Darley executed this frontispiece, meant that relatively few people actually went to the poorhouse because federal legislation sought to alleviate the sufferings of families who had lost sons and fathers as breadwinners during the conflict. In the next decade, reforms similar to those of Great Britain effectively outlawed the placing of children, the aged, infirm, and sick in poorhouses. But the unsavoury reputation of the American poorhouse prior to the 1860s would certainly have affected Darley's interpretation of Betty's determination to die outside such an institution. Certainly one can better appreciate Fanny Robin's pathetic death in Thomas Hardy's Far from the Madding Crowd (September 1874 instalment) if one has already encountered Betty Higden's dying under an oak tree; Hardy's illustrator, Helen Paterson Allingham, elected to show a desperate young woman, pregnant and friendliness, sleeping outside in She opened a gate within which was a haystack rather than dying inside the Casterbridge Union Workhouse, which appears as a shadowy presence in the initial-letter vignette for that number.

Betty Higden in the original and later editions, 1865-1875

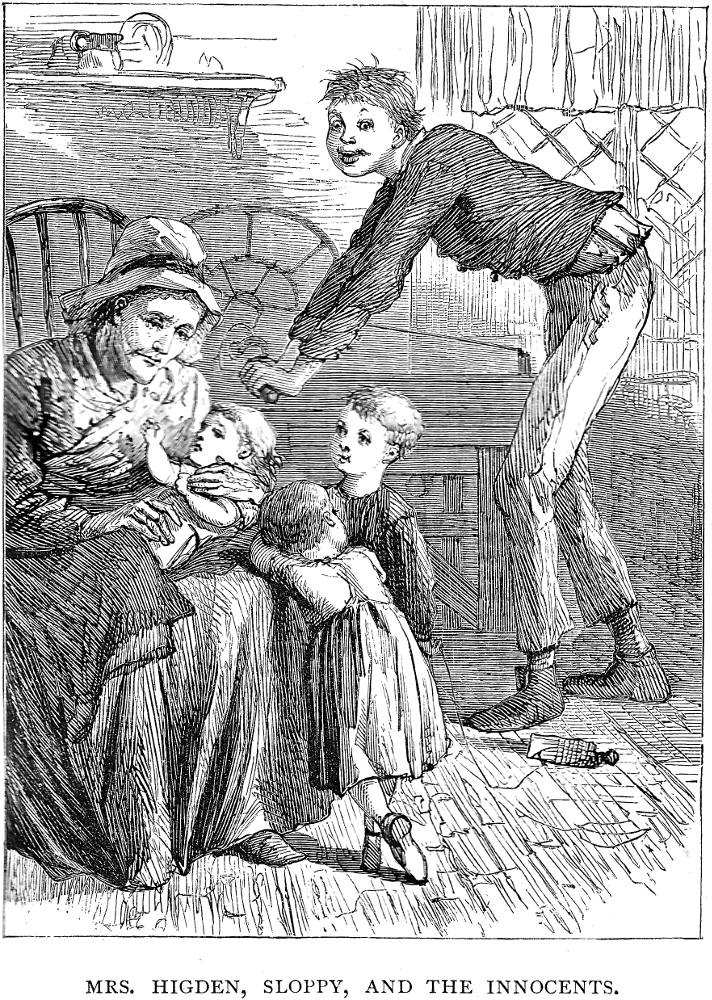

Left: Marcus Stone's December 1865 serial illustration of the interior of Betty Higden's cottage, Our Johnny.Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's study of the noble widow and her family, Mrs. Higden, Sloppy, and the Innocents (1867). Right: James Mahoney's Household Edition illustration of the death of Betty Higden near the Thames paper-mill, Lizzie Hexam very softly raised the weather-stained grey head, and lifted her as high as Heaven (1875).

Above: Marcus Stone's realistic interpretation of Betty Higden's escaping the clutches of "The Parish" and the well-meaning inhabitants of the Thames market-town,The Flight (Part 13, May 1865).

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "The Illustrators of Our Mutual Friend, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood: Marcus Stone, Charles Collins, Luke Fildes." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton: Ohio U. P., 1980. Pp. 203-228.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [40 composite wood-block engravings]. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901 [based on the original nineteen-month serial and the two-volume edition of 1865].

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1866. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1875.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 21: The Other Novels." The Dickens Picture-Book. The CharlesDickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp.441-442.

Hardy, Thomas. Far from the Madding Crowd. Ed. Sir Leslie Stephen. The Cornhill Magazine. Illustrated by Helen Paterson Allingham. London: Smith-Elder, January-December 1874. Vols. 29 and 30.

Historical Overview of the American Poorhouse System. "Socio-Political Overview: What Were Poorhouses?" Accessed 13 November 2015. http://www.poorhousestory.com/history.htm.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. (1899). Rpt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2004.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

"Our Mutual Friend — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Queen's University, Belfast. "Charles Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Clarendon Edition. Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June 1864-December 1865." Accessed 12 November 2105.

Richardson, Ruth. Dickens and the Workhouse: "Oliver Twist" and the London Poor. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 16 November 2015