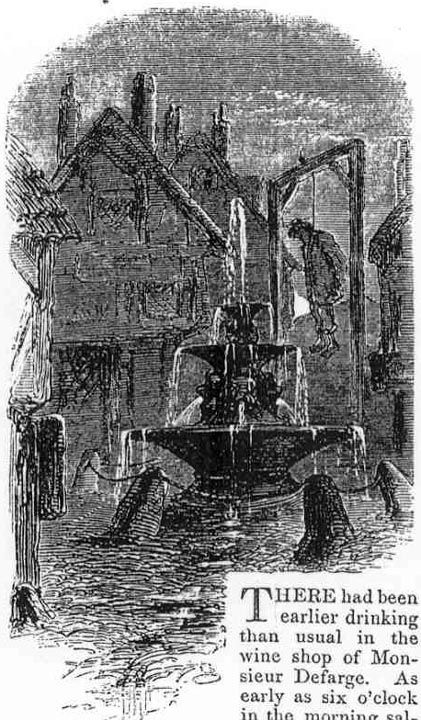

"The Fountain — An Allegory" by Harry Furniss — eleventh illustration for "A Tale of Two Cities" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

He [The Marquis St. Evrémonde] was driven on, and other carriages came whirling by in quick succession; the Minister, the State-Projector, the Farmer-General, the Doctor, the Lawyer, the Ecclesiastic, the Grand Opera, the Comedy, the whole Fancy Ball in a bright continuous flow, came whirling by. The rats had crept out of their holes to look on, and they remained looking on for hours; soldiers and police often passing between them and the spectacle, and making a barrier behind which they slunk, and through which they peeped. The father had long ago taken up his bundle and hidden himself away with it, when the women who had tended the bundle while it lay on the base of the fountain, sat there watching the running of the water and the rolling of the Fancy Ball — when the one woman who had stood conspicuous, knitting, still knitted on with the steadfastness of Fate. [Book Two, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Seven, "Monseigneur in the City," 104: the picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary

The illustration combines three visual themes that occur in the previous narrative-pictorial sequences: Phiz's baroque fountain in the public square in St. Antoine, the inconsequential nature of the decadent aristocracy of pre-revolutionary France, and the knitting of the inscrutable Moira figure of Madame Therèse Defarge, calculating and implacable as she minutely records the transgressions of the upper class. For the moment, Madame Defarge is content to be the spinner of lives marked for termination, the Fate known as Clotho; all too soon, she will enact the roles of the other two Moirae, Parcae, or Fates from Greco-Roman mythology: Lachesis, the apportioner of the thread of life (to which Dickens obliquely alludes in the title of the second book, "The Golden Thread"), and Atropos, the merciless severer of that thread. Her presence beside the ornate, Rococco fountain in the Furniss illustration, juxtaposes the future deaths of the pillars of the Ancien Régime against the life-affirming waters of the community's fountain; thus, Furniss complicates Dickens's much simpler use of the fountain image in Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44); there, the town pump had been the centre of the putative community of Eden in the architect's drawing, as seen in Phiz's October 1843 steel-engraving The Thriving City of Eden as it Appeared on Paper. Later, the fountain in the courtyard of the building in which Tom Pinch is cataloguing books serves the centre of Pinch's emotional and creative life as organizing librarian of Old Martin's collection.

Ewald Mengel regards the fountains in this later novel both traditionally, as "A symbol of life and fecundity" (26), and innovatively, as "closely associated with the passing of time, with fate and death" (26); in this illustration Furniss seems to anticipate Mengel's late twentieth-century interpretation as the illustrator juxtaposes Madame Defarge, the patient avenger recording the names of future victims, and St. Antoine's source of drinking water, strategically located opposite the suburb's informal community centre, the wine-shop of the Defarges. In the passage which Furniss's "allegorical" illustration realizes, comments Mengel,

The running water of the fountain is thus symbolically equated with the flow of time, and with death, the knitting of Mme Defarge recalling the activities of the Parcae of Greek mythology, who spin the thread of existence and have the power to cut it short at their will. Significantly, Dickens only concentrates on the death-bringing aspects of the 'goddess of fate', Mme Defarge knitting a register of sins of the aristocracy to be presented on 'doomsday', the day of revolution. [28]

Although the previous illustrators have all given prominence to the figure of Madame Defarge as the patient spider, laying her web methodically against the day when she will ensnare and annihilate her enemies, fewer of these nineteenth-century illustrators have attempted to render visually the notion of the fountain as emblematic of the river of life. By the time that readers encounter Furniss's allegorical study of the knitter and the elaborate fountain, the relevant paragraph realised is some eight pages behind them, and the text is now describing the meeting of the representatives of two very different generations of St. Evrémondes: the young, idealistic Liberal, and the inveterate old sinner, whose meeting at the Marquis' chateau is realized inCharles Darnay and The Marquis. The fountain appears prominently in just one of Phiz's monthly illustrations, The Stoppage at the Fountain (see below), and just once in John McLenan's more extensive sequence of small- and medium-sized wood-engravings for Harper's Weekly, the fountain in this case not being the scene of the child's death in St. Antoine, but the source of drinking water for the village near the Marquis' chateau, now polluted by the blood of his murderer in the untitled headnote vignette for Book Two, Chapter Fifteen, "Knitting" (see below): "The traditional symbol of life, the fountain, is here closely linked with a symbol of death, the gallows that throws its shadow upon the water. In the same nanner, the village life is 'poisoned' by Monseigneur and his class" (Mengel, 29). As the smoke from a fallen "flambeau" (110 — which is not a part of the urban scene, but occurs at the opening of Book Two, Chapter 9, "The Gorgon's Head," at the chateau of the Marquis) or link carried by a postboy drifts above the communal fountain, Madame Defarge seems to be having a vision of elegantly dressed aristocrats whose names she is recording in coded knitting. They exist in her imagination (and probably in her list in the knitting) in Furniss's "allegory," but in the text have come swirling by in their carriages, perhaps on their collective way to the delights of Versailles after attending such sophisticated urban entertainments as the Grand Opera and the Comedy.

The readers of the serial published in Great Britain, in theAll the Year Roundweekly numbers, had no such visual reinforcement of these themes; only the English purchasers of the monthly parts had the benefit of the Phiz steel-engraving The Stoppage at the Fountain (Part Three, August 1859), in which the fountain seems to shed copious tears that become a curtain of water over the dead child at its foot, with the Baroque cupidons both forming a second chorus of mourners and mirroring the fraught condition of contemporary French society. A lone cherub standing at the top, supported by brethren alike in form but compelled by the sculptor to carry their privileged brother, the water-pourer, aloft for eternity. These symbolic details in the original 1859 illustration may shed some light on Furniss's terming his illustration of Madame Defarge knitting as The Fountain — An Allegory; to be an allegory, the picture must possess a second, distinct meaning above its literal or purely visual meaning. Furniss seems to be using the aristocratic figures arising from the flambeau as a metaphor for the decadent regime that the Revolution will sweep away: they are young, physically attractive, elegantly dressed, and engaged in purely social activities. They therefore hardly constitute a true aristocracy since they lack the moral and intellectual capacities of those "best fitted to govern." Furniss does not represent any of the book's other fountains.

Whereas the novel's third fountain, that immediately in front of the chateau, does not occur in either Phiz's or McLenan's narrative-pictorial sequence, John McLenan in Harper's Weekly does offers several instances of knitting women, both with Madame Defarge in her shop (as Phiz does) and with her colleagues at the scaffold in the the untitled headnote vignette for Book Three, Chapter Fifteen, "The Steps Die Out Forever," in which three repulsive hags (presumably, the Vengeance, standing centre, and two of her St. Antoine cronies, but surely intended by McLenan to be a grisly parody of the three Moirae) exemplify in the thirteenth and final American instalment the Fates who are cheated of the blood of the Darnays.

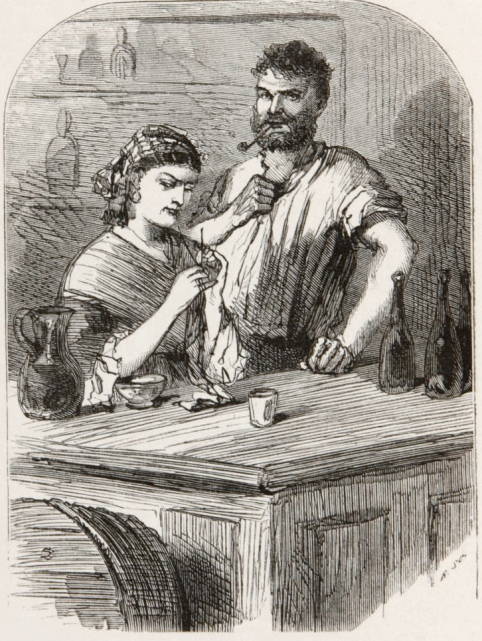

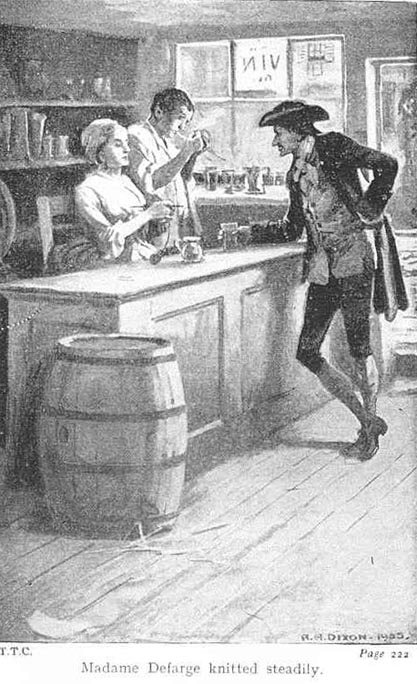

The other aspect of the Furniss "allegory" is the patient knitter dreaming of vengeance, Madame Defarge, for whom he had no shortage of models from previous series. For example, in the first of Fred Barnard's two studies of Madame Defarge as community leader in the Household Edition, Madame Defarge has laid aside her knitting on the counter of to assimilate the testimony of the three Jacques in The Wine-Shop, coolly picking her teeth, while in the second study, Saint Antoine (see below: Book Two, Chapter Sixteen), she hears the grievances of the female half of the population as men lounge in the street. In contrast, A. A. Dixon's image of Madame Defarge lacks any suggestion of malevolence; rather, the knitter behind the bar who is studying the police spy, John Barsad, in Madame DeFarge Knitted Steadily (see below), is dressed in bourgeois fashion, and is as intent upon her needlework as upon her inquisitive visitor. She seems perfectly placid — not the relentless harpy of the revolutionary scenes in Phiz, McLenan, and Barnard, but behind the tranquil exterior is the vindictive recorder of wrongs inflicted upon her family and her class.

Whereas Dixon's illustration of the Marquis, gazing placidly out his carriage window at the raving father of the dead child, in "Killed!" shrieked the man includes neither the fountain, nor the tragic chorus of grieving women, nor yet the dread avenger, Madame Defarge, Furniss's study melds the elements of the paragraph realized — the fountain as emblematic of the waters of life and the steadfast Madame Defarge as the exemplar of Fate — with an entirely new element, the sputtering torch of liberty, from whose smoke emanate the spritely figures of gorgeously dressed and coiffed courtiers, bowing to one another, and gaily dancing. One senses that they are very much on the mind of the patient knitter, despite the fact that she remains focussed on her work and does not look u The swirling actions of the dancers in the smoke are repeated in the contortions of the cupidons in the fountain. In contrast to both groups, Madame Defarge is a plain, respectably dressed, unadorned, serviceable pillar. The meaning of the allegorical torch is not immediately clear, but one senses that this symbol portends the eradication of all but the memory of the dancing phantoms in the upper register.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities(1859) — the last Dickens's novel "Phiz" Illustrated

- Costume Notes on A Tale of Two Cities

- List of Plates by Phiz for the 1859 Monthly Instalments

- John McLenan's Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Eight Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (1874)

- A. A. Dixon's Illustrations for the Collins Pocket Edition of A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

Relevant Illustrations from earlier editions, 1859, 1867, 1874, and 1905.

Left: Phiz's introduction of the fountain motif in The Stoppage at the Fountain (1859).

Left: Barnard's Household Edition description of the Parisian ghetto, Saint Antoine (1874), showing Madame Defarge as a community leader.

Left: McLenan's indictment of the arbitrary and barbarous justice of the Old Regime — the untitled headnote vignette for Book Two, Chapter Fifteen. Centre: Eytinge's dual character study of the would-be avengers of the past wrongs of the Old Regime, Monsieur and Madame Defarge (1867). Right: Dixon's wine-shop proprietors coolly assess the government spy in Madame DeFarge knitted steadily (1905).

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1988.

Bolton, H. Phili "A Tale of Two Cities." Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987, 395-412.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974. IX (1859-61).

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. All the Year Round. 30 April through 26 November 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. 7 May through 3 December 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities andGreat Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Mengel, Ewald. "The Poisoned Fountain: Dickens's Use of a Traditional Symbol of Life in A Tale of Two Cities." Dickensian 80/1 (Spring 1984): 26-32.

Created 12 November 2013

Last modified 8 January 2020