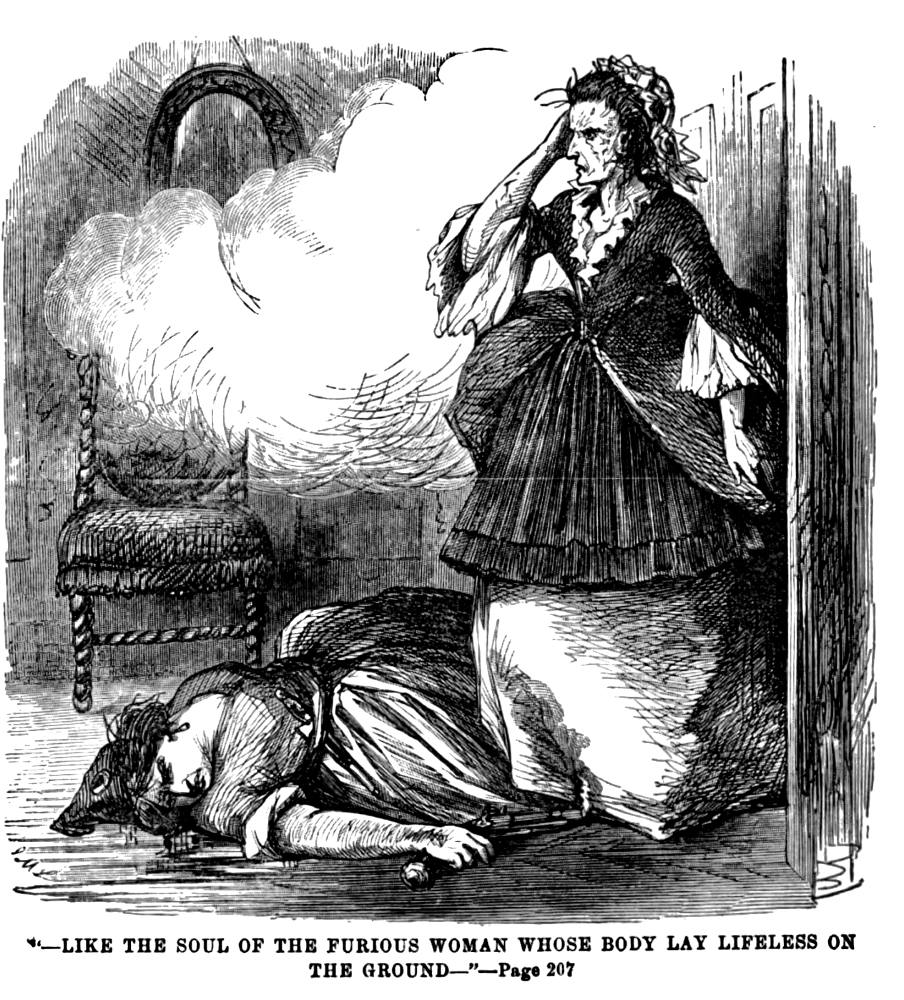

"Struggle between Miss Pross and Madame Defarge" by Harry Furniss — final

illustration for "A Tale of Two Cities" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated: The Clash of National Characters

Afraid, in her extreme perturbation, of the loneliness of the deserted rooms, and of half-imagined faces peeping from behind every open door in them, Miss Pross got a basin of cold water and began laving her eyes, which were swollen and red. Haunted by her feverish apprehensions, she could not bear to have her sight obscured for a minute at a time by the dripping water, but constantly paused and looked round to see that there was no one watching her. In one of those pauses she recoiled and cried out, for she saw a figure standing in the room.

The basin fell to the ground broken, and the water flowed to the feet of Madame Defarge. By strange stern ways, and through much staining blood, those feet had come to meet that water.

"If they are not in that room, they are gone, and can be pursued and brought back," said Madame Defarge to herself.

"As long as you don't know whether they are in that room or not, you are uncertain what to do," said Miss Pross to herself; "and you shall not know that, if I can prevent your knowing it; and know that, or not know that, you shall not leave here while I can hold you."

"I have been in the streets from the first, nothing has stopped me, I will tear you to pieces, but I will have you from that door," said Madame Defarge.

"We are alone at the top of a high house in a solitary courtyard, we are not likely to be heard, and I pray for bodily strength to keep you here, while every minute you are here is worth a hundred thousand guineas to my darling," said Miss Pross.

Madame Defarge made at the door. Miss Pross, on the instinct of the moment, seized her round the waist in both her arms, and held her tight. It was in vain for Madame Defarge to struggle and to strike; Miss Pross, with the vigorous tenacity of love, always so much stronger than hate, clasped her tight, and even lifted her from the floor in the struggle that they had. The two hands of Madame Defarge buffeted and tore her face; but, Miss Pross, with her head down, held her round the waist, and clung to her with more than the hold of a drowning woman.

Soon, Madame Defarge's hands ceased to strike, and felt at her encircled waist. "It is under my arm," said Miss Pross, in smothered tones, "you shall not draw it. I am stronger than you, I bless Heaven for it. I hold you till one or other of us faints or dies!" [Book Three, "The Track of a Storm," Chapter 14, "The Knitting Done," 348-351: with emphasis added for Hammerton's Caption]

Commentary

Whereas Dickens's original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, probably in conjunction with the author in order not to telegraph the dramatic conclusion to the reader of the monthly parts in advance of that reader's encountering the passage in the accompanying text, avoided the scenes in which Sydney Carton meets his death on the scaffold disguised as Charles Darnay and Miss Pross's love for Lucie proves stronger than Madame Defarge's hatred of the Evrémondes, Harry Furniss has depicted both highly dramatic scenes — even if he has made Carton on the Scaffold the volume's frontispiece, and thereby distanced it from the accompanying text.

Although the murky "dark plate" of Carton and the innocent victim of an arbitrary judgment awaiting transportation in the Conciergerie, Sydney Carton and the little Seamstress makes little impression initially, the wrestling match between the two determined viragoes suitably pits the avenging against the protective angel, although the picture is situated after the outcome of this life-and-death grappling in the letterpress. Good as the illustration is in its depiction of these female (but not feminine) Titans, it cannot match the sentimental force of Dickens's description of this mortal combat, and the effectiveness of the dialogue:

"Nevertheless, you shall not get the better of me. I am an Englishwoman."

Each spoke in her own language; neither understood the other's words; both were very watchful, and intent to deduce from look and manner, what the unintelligible words meant. [349]

Set in the deserted rooms of Tellson's Paris headquarters, this is the climactic scene in many of the film adaptations, as it pits the supremely cunning and physically powerful Térèse Defarge, married as much to the bitterness at having lost her entirely family as to Ernest Defarge — and mother only to her lifelong grudge against the destroyers of her family — against the stolid Miss Pross, resolute protector of her "Ladybird." In the 1935 David O. Selznick film, Madame Defarge, the ardent but somewhat haglike sans culotte played with passionate and menacing conviction by forty-eight-year-old Blanche Yurka, has heretofore been unstoppable, but in Miss Pross (played in that same film by fifty-two-year-old Edna May Oliver), whom Dickens establishes as an avowed monarchist and stalwart Briton, the vengeful spirit of Revolution has met her match. Viewed even seventy-five years later, this scene (at least in their minds) brings viewers to their feet, cheering for the victory that ensures the escape of the Darnays. The Furniss illustration effectively realizes the mighty conjunction of these binary opposites in a Dickensian clash of the Titans: "You might, from your appearance, be the wife of Lucifer," said Miss Pross, in her breathing. "Nevertheless, you shall not get the better of me. I am an Englishwoman" (349).

Already in The Perils of Certain English Prisoners in the extra-Christmas Number of Household Words for 1857 we have seen a virulent strain of xenophobia and racism, Dickens's extreme response to the Sepoy Mutiny, but these biases manifest themselves here quite differently as Miss Pross and her Satanic opposite are not entirely uni-dimensional characters whom we have heretofore detested or approved of. Madame Defarge possesses on her side a compelling argument for the destruction of the corrupt aristocracy that does not equate with the low, villainous Christian George King's unmitigated perfidy in the Collins-Dickens novella of 1857. Each of these female antagonists in the 1859 serial is, in fact, what Lisa Robson has termed "a feminine aberration" (31); Miss Pross, for instance, is a peculiar combination of subservience (to her scapegrace brother Solomon as well as to her charge, Lucie) and aggression, whereas Madame Defarge is a married woman without children who runs a business, consorts with and even directs the members of the Jacquerie, and is consumed by a most unfeminine blood lust. Although both give "faithful service" to their convictions, in this ultimate scene there is never a moment in which the reader identifies here with the blood-thirsty Frenchwoman against the innocent Briton, previously not much more than a crotchety "stereotypical Victorian old maid" (Waters 119), despite her red hair, who has already stridently broadcast her pride in being a British subject, even in the midst of the Reign of Terror, when such protestations might result in arbitrary arrest:

"For gracious sake, don't talk about Liberty; we have quite enough of that," said Miss Pross.

"Hush, dear! Again?" Lucie remonstrated.

"Well, my sweet," said Miss Pross, nodding her head emphatically, "the short and the long of it is, that I am a subject of His Most Gracious Majesty King George the Third;" Miss Pross curtseyed at the name; and as such, my maxim is, Confound their politics, Frustrate their knavish tricks, On him our hopes we fix, God save the King!" [a now little-sung verse from the 1745 version of "God Save the King!"]

Mr. Cruncher, in an access of loyalty, growlingly repeated the words after Miss Pross, like somebody at church. [Book Three, Chapter Seven, "A Knock at the Door," 276]

Indeed, Catherine Waters' interpretation emphasizes Dickens's investing Miss Pross with the national attributes of the English as she closes in mortal combat with her Gallic opposite:

But her wiry strength and characterisation as a decidedly _English_grotesque also make her a fit opponent for Madame Defarge. While Madame Defarge represents a repudiation of the ideals Miss Pross so vigilantly protects in the person of her 'Ladybird', it is primarily the national differences between the two women that determine their fateful encounter. As the two of them are set face to face in the narrative, other categories of difference — gender, generational and class difference — are ostensibly overridden by the opposition of nationalities. What distinguishes the struggle between Madame Defarge and Miss Pross is not its commonly proclaimed thematic function as a 'contest between the forces of hatred and love', but its characterisation as a confrontation between France and England. [119-20]

Intuitively, Furniss apprehends and communicates this "national difference" in Miss Pross's stubborn defiance of the female Lucifer as this crusty, old maid in a proper eighteenth-century English spinster's cap stares down her muscular adversary in the Phrygian cap, the outward and visible sign of her rebellious spirit. Perhaps to exonerate her of the charge of manslaughter, Furniss has Miss Pross in a defensive posture as Madame Defarge swings wide and lunges forward. Only their dresses imply their gender: their faces and arms are thoroughly masculine, and this fight to the death seems utterly out of place in the domestic setting, characterized by the broken porcelain basin in the foreground. Several other illustrators, including Phiz and Sol Eytinge, Junior, have interpreted Miss Pross as a mere old maid, albeit one of stubborn and protective disposition, whose victory at this crucial juncture therefore must be a matter of chance — or, perhaps, Providence, which Dickens in his 5 June 1860 letter to Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton expressed himself as being quite justified in using here:

I am not clear, and I never have been clear, respecting that canon of fiction which forbids the interposition of accident in such a case as Madame Defarge's death. Where the accident is inseparable from the passion and emotion of the character, where it is strictly consistent with the whole design, and arises out of some culminating proceeding on the part of the character which the whole story had led up to, it seems to me to become, as it were, an act of divine justice. And when I use Miss Pross (though this is quite another question) to bring about that catastrophe, I have the positive intention of making that half-comic intervention a part of the desperate woman's failure, and of opposing that mean death — instead of a desperate one in the streets, which she wouldn't have minded — to the dignity of Carton's wrong or right; this was the design, and seemed to be in the fitness of things. [Letters, IX: 259-260]

However, perhaps neither Fred Barnard nor Furniss was comfortable with the notion that Madame Defarge is the victim of mere caprice or accident (or for that matter Providence) in that these later artists made Miss Pross as physically formidable as her adversary, whereas Phiz, Eytinge, and McLenan have made her a far less imposing figure and therefore the victor by virtue of the fortunate accident of her discharging Madame Defarge's own pistol, a symbol of her expropriation of masculine power. Even as she contemplates betraying her own husband (whom she, like Lady Macbeth with respect to her husband's murdering the venerable King Duncan in Shakespeare's tragedy of bloody ambition, dismisses as too tender-hearted about Doctor Manette to consign him, his child, and grandchild to the guillotine) and arranging the execution of both Lucie and her child on trumped-up charges, she perishes in a burst of gunpowder by inadvertence caused by her own negligence in the care and storage of a destructive implement more properly from the political, martial, and therefore masculine sphere.

Having abandoned her knitting-needles for weapons of close combat, Madame Defarge, too, changes over the period encompassed by these illustrated editions, that is,from the two serials of 1859 to Charles Dickens Library Edition of 1910, as a number of critics, including Albert Hutter, have noted: "Madame Defarge begins to age soon after Dickens' death. The "Household Edition" (New York: Harper, 1878), for example, shows a square-jawed, muscular Madame Defarge, looking very much like a man, on the title page. She looks older, heavier, and uglier by the end of the novel ( 154), but is at her worst on 79, where she bears a remarkable resemblance to the aging Queen Victoria" (461). In asserting that illustrators' conceptions of Madame Defarge began to shift in the 1870s, Waters overlooks the more conventional depictions of her as a not-unattractive publican earlier in the story as realised by Barnard and Furniss:

In the original 'Phiz' drawings, she is shown as a strong, young woman, with a beautiful but determined face, and dark hair. The illustrations set her in contrast with the blonde-haired beauty of Lucie Manette. However, many subsequent versions of Madame Defarge in film and illustration have made her a witch. According to Hutter, the Harper and Row cover to A Tale of Two Cities, for example, 'shows a cadaverous old crone, gray-haired, hunched over her knitting, with wrinkles stitched across a tightened face' [Hutter, 457]. In the 1935 film, starring Ronald Colman, Madame Defarge is a rather haggard and plain-faced woman, with dark circles beneath her eyes, whose grim appearance contrasts with the fair complexion and rosy lips of the beautiful Lucie.

This change in the visual representation of Madame Defarge denotes a cultural shift in the construction of female subjectivity from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, and highlights Defarge's function in the novel. As a crucial part of the novel's effort to solve the problems posed by the Revolution, Madame Defarge serves as the monstrous female 'other' against which the norms of Victorian middle-class femininity and domesticity can be invoked. She is characterized as dangerously sexual and violent, oblivious of her wifely role and domestic responsibilities, lacking the feminine virtues of meekness, compassion and purity shown by Lucie and ominously intimate with like-minded women. All of these traits are informed by a Victorian middle-class conception of female subjectivity. Later representations showing Madame Defarge as a witch provide evidence of a historical change in the significance of femininity and domesticity as a cultural norms. "In order to continue serving as the 'other' woman, Madame Defarge is represented as old, ugly and deformed, because overt sexual attractiveness, assertiveness and freedom from convention have become attributes of the new twentieth-century heroine. [Waters 116-117]

In fact, in this final illustration of these champions of traditional (English) and radicalized (French) societies, Furniss has depicted these combatants in a manner quite inconsistent with his earlier representations of them: in Miss Manette and Mr. Lorry Interrupted and Doctor Manette's 'Old Companion'Furniss underscores Miss Pross's propensity to act rather than passively acquiesce in male decisions, but the slight if somewhat assertive governess in these earlier illustrations bears little resemblance to the powerful wrestler here. In many ways, it seems as if Furniss has derived this British bulldog version of Miss Pross directly from Barnard, who from the first regards Miss Pross's assertiveness in the scene at the Royal George as a sign of her masculine character, so that he introduces her not as the "slight," and generally somewhat timid governess of Phiz's illustrations, but as a large, strong-boned, broad-shouldered woman with masculinized facial features in And smoothing her rich hair with as much pride as she could possibly have taken in her own hair if she had been the vainest and handsomest of women, the illustration which accompanies Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," Chapter 6, "Hundreds of People." Barnard depicts Miss Pross only twice: he initially suggests that she is both feminine (a surrogate mother who is taking pride in her adopted child's golden hair) and masculine (physically as well as emotionally domineering) in order later on to make her more plausible as a match for the French termagant, who is both a far cry from his own coolly competent community organizer of Saint Antoinein "Still Knitting" and Phiz's original conception of a beautiful, demure knitter who is blonde Lucie Manette's brunette doppelganger in Phiz's wine-shop scenes and the monthly wrapper. "Madame Defarge in The Wine-Shopresembles Lucie After the Sentence and The Knock at the Door; Lucie's expressions are naturally quite different, but the features of the two women are quite similar — both women are young and attractive. What appear to be mirror images of the two women are placed opposite each other on the wrapper of the original edition" (Hutter, 461).

Whereas Phiz is able to maintain Madame Defarge's fine, female figure in The Sea Rises, his title forthe violent post-Bastille scene in which the Saint Antoine mob, whipped up to a frenzy by Madame Defarge and her companion, The Vengeance, abuse and then hang Foulon, functionary of the ancien régime, Barnard wisely decides to leave the fair publican out of the picture altogether. Thus, we can put Furniss's depiction of the mighty female adversaries as the novel's concluding illustration (rather than the scene of Carton disguised as Darnay on the public scaffold, which Furniss has strategically made the frontispiece in order to end his visual program on a note of triumph rather than of tragedy) in the context of the Household Edition volume of 1874, in which the ultimate and therefore climatic illustration focuses on the sacrifice of Carton in The Third Tumbrelrather than the accidental triumph of Miss Pross's English tenacity and devotion to a living family over Madame Defarge's French passion and commitment to seeking vengeance for those destroyed by an oppressive system and the vicious sociopaths whom it has fostered. Only in Furniss's sequence when she shifts from feminine plotting and enabling masculine action to becoming an active abettor of institutional injustice and class warfare does Furniss transform her from the determined but not unattractive _petite bourgeois_of The Fountain — An Allegoryand Still Knitting into the formidable wrestler (still wearing her tricolour rosette, but now on a Phrygian cap) with the masculine profile and kinetically charged, lean body that occupies most of the frame as she determinedly attempts to push her English opponent out of the frame.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities(1859) — the last Dickens's novel "Phiz" Illustrated

- Costume Notes on A Tale of Two Cities

- List of Plates by Phiz for the 1859 Monthly Instalments

- John McLenan's Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Eight Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (1874)

- A. A. Dixon's Illustrations for the Collins Pocket Edition of A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

Relevant Illustrations from earlier editions: 1859, 1867, 1874, and 1905

Above:The Double Recognition by Hablot Knight Browne in the seventh monthly number (December 1859) involves a very different Miss Pross.

Left: McLenan's 26 November 1859 depiction of the conclusion of the struggle, Like the soul of the furious woman whose body lay lifeless on the ground. Centre:Eytinge's middle-aged governess in Mr. Lorry and Miss Pross (1867). Right: Dixon's illustration of Carton and Darnay exchanging clothing, "Change that coat for this of mine" (1905).

Above: Barnard's Household Edition illustration of the confrontation of two immovable forces in Book Three, Chapter Fourteen, "You might, from your appearance, be the wife of Lucifer," said Miss Pross, in her breathing. "Nevertheless, you shall not get the better of me. I am an Englishwoman"(1874).

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1988.

Bolton, H. Phili Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987.

Cooper, Fox. The Tale of Two Cities: Or, The Incarcerated Victim of the Bastille. An Historical Drama, in a Prologue and Four Acts. Adapted from Charles Dickens's Story. No. 780. London: Dicks' Standard Plays, n. d.

Dickens, Charles. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974. IX (1859-61).

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. All the Year Round. 30 April through 26 November 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. 7 May through 3 December 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities andGreat Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Hutter, Albert D. "Nation and Generation inA Tale of Two Cities. PMLA 93 (1978): 448-462.

Robson, Lisa. "The 'Angels' in Dickens's House: Representations of Women in A Tale of Two Cities." Dalhousie Review, no. 3 (Fall 1992): 311-33. Rpt. Bloom's Modern Critical Interpretations: Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. New York: InfoBase, 2007, 27-48.

Sanders, Andrew. A Companion to A Tale of Two Cities. London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

Selznick, David O. (producer). A Tale of Two Cities [black-and-white, soundfilm adaptation of Dickens's novel]. MGM/United Artists, 1935.

Waters, Catherine. "A Tale of Two Cities."Dickens and the Politics of Family. Cambridge: Cambridge U. , 1997, 122-49. Rpt. Bloom's Modern Critical Interpretations: Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. NewYork: InfoBase, 2007, 101-28.

Created 5 January 2014

Last modified 13 January 2020