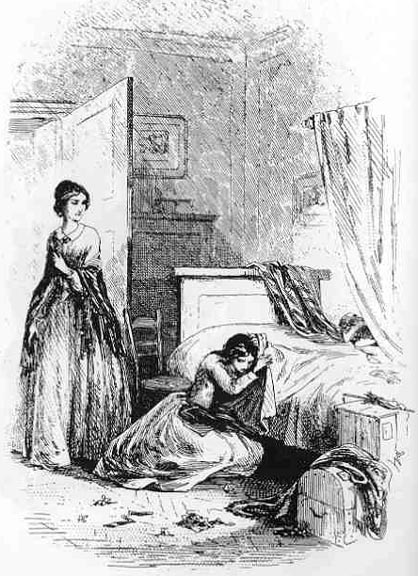

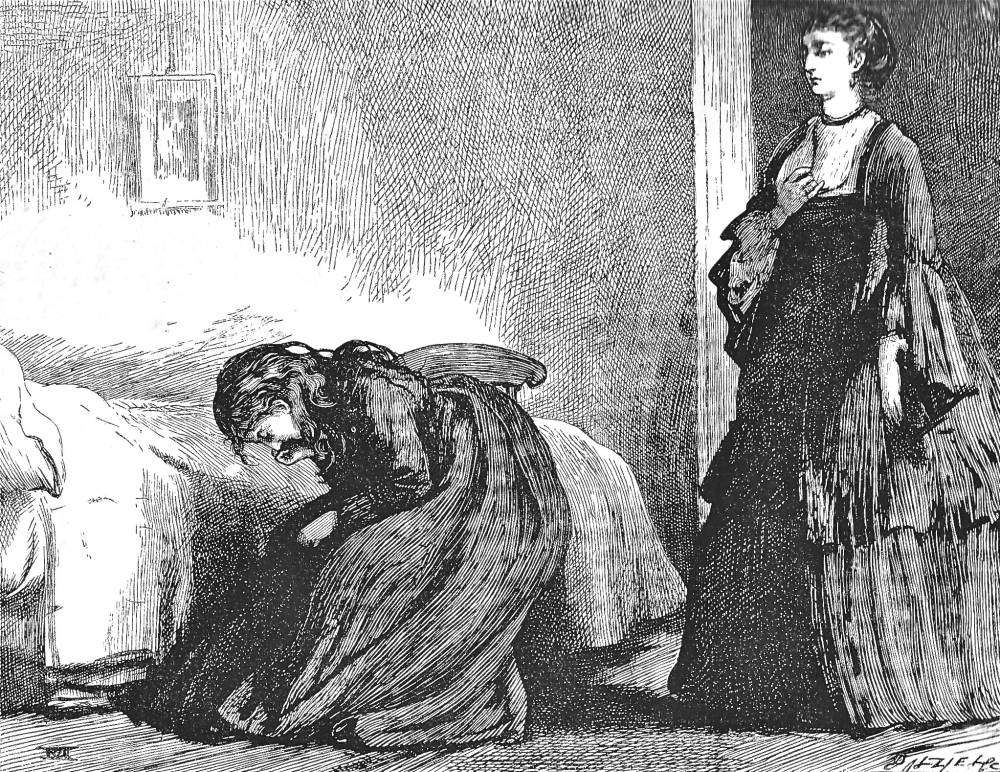

"Tattycoram and Miss Wade" by Harry Furniss — thirteenth illustration for "Little Dorrit" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

"Come here, child." She had opened a door while saying this, and now led the girl in by the hand. It was very curious to see them standing together: the girl with her disengaged fingers plaiting the bosom of her dress, half irresolutely, half passionately; Miss Wade with her composed face attentively regarding her, and suggesting to an observer, with extraordinary force, in her composure itself (as a veil will suggest the form it covers), the unquenchable passion of her own nature.

"See here," she said, in the same level way as before. "Here is your patron, your master. He is willing to take you back, my dear, if you are sensible of the favour and choose to go. You can be, again, a foil to his pretty daughter, a slave to her pleasant wilfulness, and a toy in the house showing the goodness of the family. You can have your droll name again, playfully pointing you out and setting you apart, as it is right that you should be pointed out and set apart. (Your birth, you know; you must not forget your birth.) You can again be shown to this gentleman's daughter, Harriet, and kept before her, as a living reminder of her own superiority and her gracious condescension. You can recover all these advantages and many more of the same kind which I dare say start up in your memory while I speak, and which you lose in taking refuge with me — you can recover them all by telling these gentlemen how humbled and penitent you are, and by going back to them to be forgiven. What do you say, Harriet? Will you go?" [Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 27, "Five-and-Twenty," 341-42: the wording of picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary: The Haughty Miss Wade

For as long as the defensive Miss Wade remains her surety, Tattycoram feels that she can continue to thumb her nose at her employers, the Meagles. The plot, in fact, requires that Tattycoram live under Miss Wade's roof long enough to acquire the documents that she has acquired from Henry Gowan regarding both Little Dorrit and Arthur Clennam.

A curious point about the present Furniss illustration is that its caption does not closely correspond to a particular passage. Although Furniss stipulates that the following passage on page 341 is the moment realised, he or his editor, J. A. Hammerton, have condensed Dickens's text substantially: _"Come here, child," said Miss Wade, opening the door. "Here is your patron, your master. You can be, again, a foil to his pretty daughter, a slave to her pleasant wilfulness, and a toy in the house showing the goodness of the family. What do you say, Harriet? Will you go?" — Dorrit, 341._This condensed version of the paragraph of dialogue sharpens Miss Wade's criticism of the Meagles, and reveals how she is manipulating "Harriet" (no pet-names for the austere Miss Wade) psychologically. Furniss shows the speaker delivering these lines with considerable hauteur, and the auditor studying the speaker critically.

As the novel opens, feeling resentful about how her adoptive family treat her as her sister's maid, self-pitying Tattycoram falls under the spell of another resentful female, Miss Wade, and runs away to be with this woman in what appears to be the only incidence in Dickens of a lesbian relationshi Later, however, after she has fallen out with the moody Miss Wade, Tattycoram repents of her decision, and returns to do her duty with her adopted family. Miss Wade's grounds for resentment are more significant than sibling rivalry — to the taint of illegitimacy (which she shares with Tattycoram) we eventually add artist Henry Gowan's cruel treatment of her. In Dickens's illustrators' rendering of this scene, Miss Wade seems to be contemplating Tattycoram's case in light of her own, and considering how she will cope with the younger woman's temperamental fits if Tattycoram is to be her close "companion."

The presence of the trunk in Phiz's version of the scene, Under the Microscope (see below), may be intended to implant in readers' minds the suggestion that the girl will discover something significant in the house (the missing legal papers). In neither Furniss's nor Phiz's illustration may we regard Tattycoram as a "handsome girl with lustrous dark hair and eyes, and very neatly dressed." In Phiz, Tattycoram is a neurotic wreck seeking shelter, whereas Furniss does not go so far as to suggest she is mentally unbalanced. In the case of the original illustrator, reading the novel in instalments, Phiz in producing his illustration would not have had the benefit of reading Miss Wade's true confession of her own circumstances in "The History of a Self-Tormentor" (Book Two, Chapter 21) in the March 1857 monthly number when he prepared the serial illustration in the autumn of 1855. Mahoney and Furniss both certainly knew about the contents of that much later chapter in what was originally serial instalment no. 16. However, only Mahoney's characterization reifies the former governess's supercilious and suspicious nature: "In her later years, she is cynically deceived by the man who encourages her to break her engagement and then abandons her in order to court another woman. In the rest of Little Dorrit, Miss Wade is a mysterious but clearly unpleasant person; Pancks . . . remarks that 'a woman more angry, passionate, reckless, and revengeful never lived'" (Thomas 124).

In his portrait of Miss Wade, Mahoney captures his subject's judgmental nature, her aloofness, and her rigid sense of herself — here, then, is a character that the reader may not like, but one with whom the reader can nonetheless sympathize. One sees little of this complexity in the images of Miss Wade Phiz and Furniss. The latter illustrator communicates her haughtiness, but little more in her stiff, unbending pose, dismissive gesture, and almost closed eyelids. Although Furniss is not nearly so interested in her, Tattycoram will be the key to uncovering a plot secret: Mrs. Clennam's having suppressed a codacil in Arthur's uncle's will awarding Little Dorrit a sizeable share in the estate. Since this information would not have come to light had Tattycoram not purloined the papers from Miss Wade, the illustration perhaps serves as a foreshadowing of the girl's beginning to revise her appreciative assessment of the calculating Miss Wade.

Related Materials: Background, Setting, Theme, and Characterization

- Mr. Merdle's suicide

- Swindlers and Society in Dickens and Carlyle

- Real and Fictional Swindlers: Lever's Davenport Dunn & the Financial Bubble of the Fifties

- Material Culture as Society Informant: Prisons in Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit

- Female Saviors in Victorian Literature: Amy Dorrit

- Prisons in Little Dorrit

- Characterization and Setting in Dickens's Little Dorrit

- Dickens's Uses of King Lear in Little Dorrit, David Copperfield, and Other Novels

- Prisons in Victorian England

Other Illustrations, 1855-1923

- Illustrations by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne) (1855-57)

- Illustrations by Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Illustrations by James Mahoney (1873)

- Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1863)

- Illustration by Harold Copping (1923)

Relevant Illustrations of Tattycoram and Miss Wade from Other Editions, 1855-1873

Left: Phiz's second illustration in the novel's first serial number, Under the Microscope (December 1855). Right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's interpretation of the maid (Harriet Beadle) known as "Tattycoram" and the middle-class malcontent, Miss Wade, Miss Wade and Tattycoram (1867).

Mahoney's 1873 composite woodblock-engraving of Miss Wade and Tattycoram early in the novel, when the maid takes refuge with her, The Observer stood with her hand upon her own bosom, looking at the girl.

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. , 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. 30 May 1857 volume].

_____. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

_____. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

_____. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

_____. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit."The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17, 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. [Rpt. of the London 1899 edition]

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1999.

Steig, Michael. "VI. Bleak House and Little Dorrit." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. , 1978, 131-298.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Created 23 May 2016

Last modified 23 January 2020