Mr. Tibbs — Furniss's twentieth illustration for Dickens's "Sketches by Boz" (1910), Chapter 1 in "Tales" (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

The installation of the Duke of Wellington, as Chancellor of the University of Oxford, was nothing, in point of bustle and turmoil, to the installation of Mrs. Bloss in her new quarters. True, there was no bright doctor of civil law to deliver a classical address on the occasion; but there were several other old women present, who spoke quite as much to the purpose, and understood themselves equally well. The chop-eater was so fatigued with the process of removal that she declined leaving her room until the following morning; so a mutton-chop, pickle, a pill, a pint bottle of stout, and other medicines, were carried up-stairs for her consumption.

"Why, what do you think, ma'am?" inquired the inquisitive Agnes of her mistress, after they had been in the house some three hours; "what do you think, ma'am? the lady of the house is married."

"Married!" said Mrs. Bloss, taking the pill and a draught of Guinness — "married! Unpossible!"

"She is indeed, ma'am," returned the Columbine; "and her husband, ma'am, lives — he — he — he — lives in the kitchen, ma'am."

"In the kitchen!"

"Yes, ma'am: and he — he — he — the housemaid says, he never goes into the parlour except on Sundays; and that Ms. Tibbs makes him clean the gentlemen's boots; and that he cleans the windows, too, sometimes; and that one morning early, when he was in the front balcony cleaning the drawing-room windows, he called out to a gentleman on the opposite side of the way, who used to live here — 'Ah! Mr. Calton, sir, how are you?'" Here the attendant laughed till Mrs. Bloss was in serious apprehension of her chuckling herself into a fit.

"Well, I never!" said Mrs. Bloss.

"Yes. And please, ma'am, the servants gives him gin-and-water sometimes; and then he cries, and says he hates his wife and the boarders, and wants to tickle them."

"Tickle the boarders!" exclaimed Mrs. Bloss, seriously alarmed.

"No, ma’am, not the boarders, the servants."

"Oh, is that all!" said Mrs. Bloss, quite satisfied.

"He wanted to kiss me as I came up the kitchen-stairs, just now," said Agnes, indignantly; "but I gave it him — a little wretch!"

"This intelligence was but too true. A long course of snubbing and neglect; his days spent in the kitchen, and his nights in the turn-up bedstead, had completely broken the little spirit that the unfortunate volunteer had ever possessed. He had no one to whom he could detail his injuries but the servants, and they were almost of necessity his chosen confidants. It is no less strange than true, however, that the little weaknesses which he had incurred, most probably during his military career, seemed to increase as his comforts diminished. He was actually a sort of journeyman Giovanni of the basement story.["Tales," Chapter 1, "The Boarding-House, Chapter the Second," 284]

Commentary

Extended caption adapted from the text: Mr. Tibbs, the landlady's husband, never goes into the parlour except on Sundays. He cleans the boots and the windows, and tries to kiss the servants. "He was actually a sort of journeyman Giovanni of the basement story." — Sketches by Boz, 284.

Although the middle-class couple who run the rooming-house on Great Coram Street, near the British Museum, are the focus of the two "Boarding-house" sketches in the original two-volume set of 1836, Dickens explores neither of them beyond their rather stereotypical surfaces, so that Mr. Tibbs is simply a well-meaningbut uxorious husband and his wife a controlling shrew. His more dashing demeanour, as a romancer of pretty maid-servants, is not established by an actual incident; rather, Furniss has based this scene on household gossip retailed by Agnes to her mistress, Mrs. Bloss. Despite the somewhat flimsy multiple-marriageplot, then, Furniss chooses instead to focus on obsequious little Mr. Tibbs as a below-stairs Lothario. One wonders what connection between himself and Mr. Tibbs Dickens saw — or were the Tibbses a reflection of his own parents?

In illustrating these early sketches first published in the Monthly Magazine and illustrated by George Cruikshank in 1836, Furniss had the precedent of two original engravings, The Boarding House (see below) and The Boarding House — II. (also below), but chose to offer up Mr. Tibbs in quite another character, depicting the oppressed husband as a romancer of a pretty maid rather than a henpecked husband.

Although little Mr. Tibbs is hardly the inebriate that Sol Eytinge, Jr., implies in his 1867 wood-engraving (an illustration that Furniss is not likely to have seen), the sexualised behaviour noted in Furniss's 1910 animated "below-stairs" illustration The Boarding House: Mr. Tibbs may be the result of the servants' plying him with gin-and-water. His attempting to kiss the young maids, moreover, seems to suggest his dissatisfaction with a marriage in which his wife treats him like one of the domestics, confining him to the kitchen and assigning him the cleaning of the boarders' boots and shoes. The couple's relationship bookends the two-part story as "The Boarding-House" begins with Dickens's describing Mrs. Tibbs' dominance, and concludes with their closing the boarding-house and going their separate ways after disposing of the furniture by auction, and dividing Mr. Tibbs' modest annuity between them. Dickens does not mention the legal grounds of the separation, which in 1836 for people of the middle class would not have been a formalized divorce.

Furniss adopts the unusual expedient of illustrating the text with a moment that is not part of the main narrator's story and is not therefore, strictly speaking, "dramatised." Rather, Mrs, Bloss's head-maid, the secondary or inset narrator, "the inquisitive Agnes," attempts to explain the social dynamics of the boarding-house in which Mrs. Bloss and her entourage have just taken up residence. Ironically, so long as it's juyst the servants that Mr. Tibbs is trying to kiss, Mrs. Bloss seems unconcerned. Furniss captures the "downstairs" scene with his usual vigour, using swirling background lines in the upper-left register to frame the dynamic moment. Even as Tibbs abandons his domestic duties, breaking away suddenly from blacking the boots and pumps at the foot of his chair to embrace the maid; adding to the energetic force of the lithograph is the maid's leaning in the embrace, perhaps to steady the tray of dishes that she is carrying — a detail added to the scene by Furniss to suggest that Tibbs has not been present at the meal just concluded. However, the illustration quite contradicts Dickens's assertion that Tibbs's spirit has been broken, and depicts him as a "journeyman Giovanni," or at least a Lothario.

Relevant Illustrations from Other Editions, 1839 through 1910

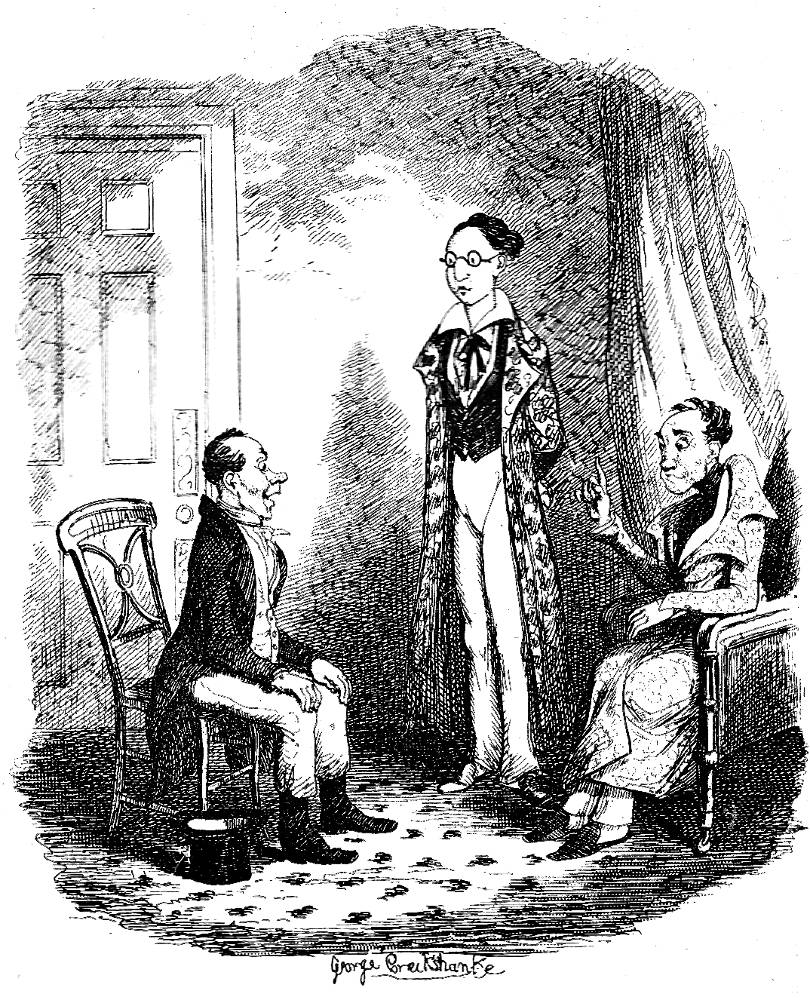

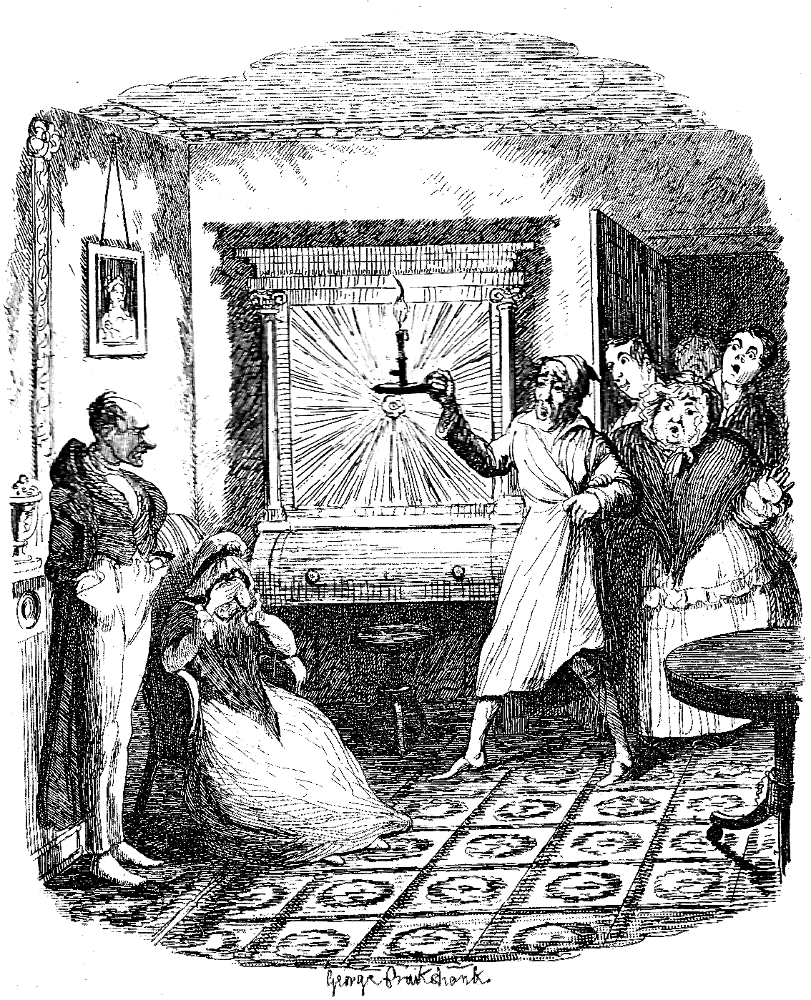

Left: Cruikshank's illustration for the first instalment of the two-part short story, The Boarding House, showing Tibbs (left), Septimus Hicks (centre), and Mr. Carlton in his dressing-gown and easy chair (1839). Centre: Cruikshank's version of the discovery scene, when the boarders find Mrs. Tibbs and Mr. Evenson in a supposedly compromising position, in The Boarding House. — II (1839).Right: Eytinge's comic study of an inebriated Mr. Tibbs's being confronted by the shrewish landlady, The Boarding-House (1867).

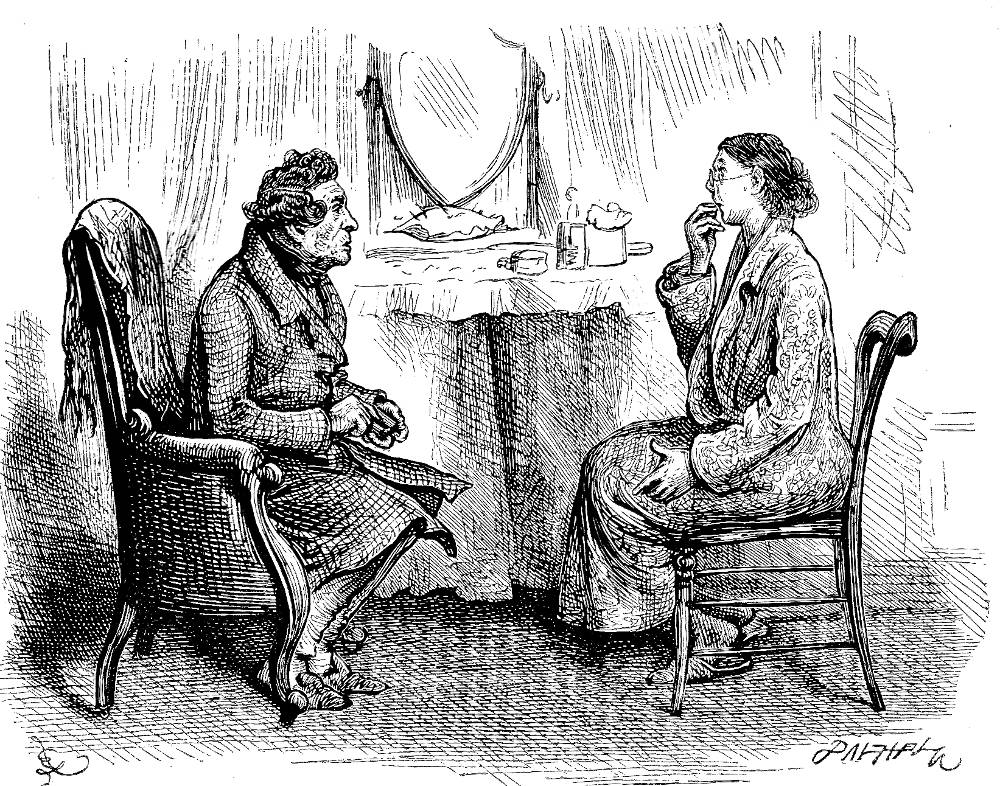

Above: The Household Edition illustration for the first part of the story, depicting young Mr. Septimus Hicks abd the invalid, Mr. Calton, about to reveal to each other their secret marriage plans in "I received a note —" he said very tremulously, in a voice like a Punch with a cold. —"Yes," returned the other, "You did." —"Exactly."—"Yes." (1876).

Above: Fred Barnard's second illustration for the story, in which the new boarder, the wealthy widow Mrs. Blossis confused about Mrs. Tibbs's use of the expression "no stomach" (as in "no appetite"), "No what?" inquired Mrs. Bloss with a look of the most indescribable alarm. "No stomach," repeated Mrs. Tibbs with a shake of the head (1876).

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. "Tales," Chapter 1, "The Boarding-House,"Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by GeorgeCruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890, 205-234.

_____. "Tales," Chapter 1, "The Boarding-House." Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition], 305-310.

_____. "Tales," Chapter 1, "The Boarding-House." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876, 130-148.

_____. "Tales," Chapter 1, "The Boarding-House." Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1, 263-300.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011, 12-15.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. , 2009.

Created 12 May 2017

Last modified 2 February 2020