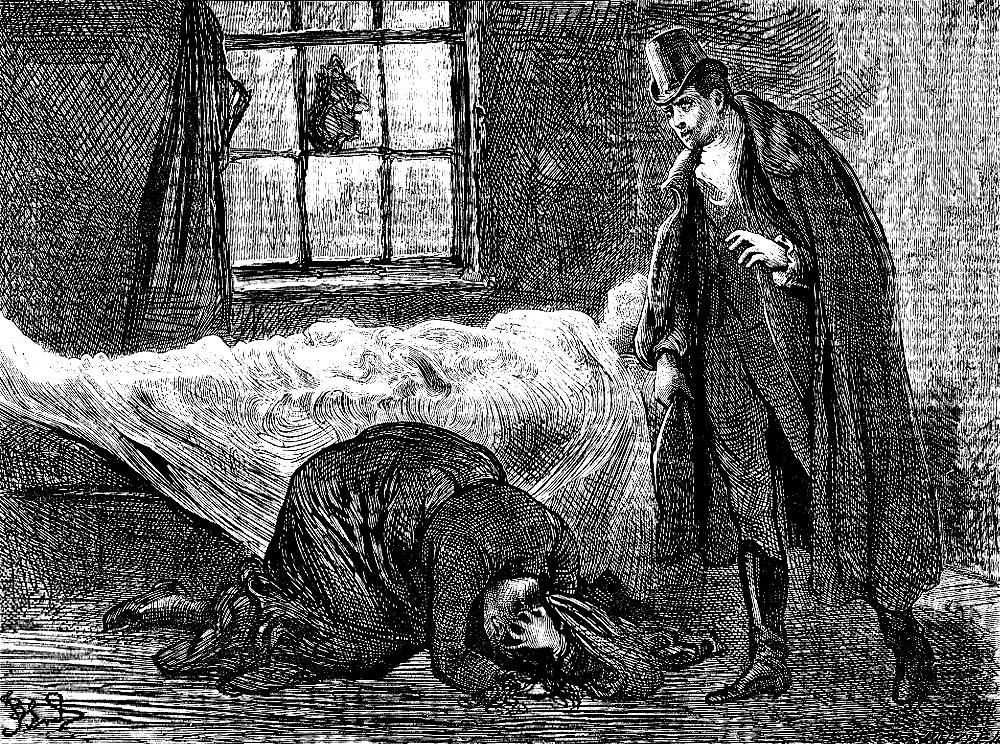

"The Black Veil" — Furniss's twenty-fourth illustration for Dickens's "Sketches by Boz" (1910), Chapter 6 in "Tales" (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

One winter's evening, towards the close of the year 1800, or within a year or two of that time, a young medical practitioner, recently established in business, was seated by a cheerful fire in his little parlour, listening to the wind which was beating the rain in pattering drops against the window, or rumbling dismally in the chimney. The night was wet and cold; he had been walking through mud and water the whole day, and was now comfortably reposing in his dressing-gown and slippers, more than half asleep and less than half awake, revolving a thousand matters in his wandering imagination. First, he thought how hard the wind was blowing, and how the cold, sharp rain would be at that moment beating in his face, if he were not comfortably housed at home. Then, his mind reverted to his annual Christmas visit to his native place and dearest friends; he thought how glad they would all be to see him, and how happy it would make Rose if he could only tell her that he had found a patient at last, and hoped to have more, and to come down again, in a few months’ time, and marry her, and take her home to gladden his lonely fireside, and stimulate him to fresh exertions. Then, he began to wonder when his first patient would appear, or whether he was destined, by a special dispensation of Providence, never to have any patients at all; and then, he thought about Rose again, and dropped to sleep and dreamed about her, till the tones of her sweet merry voice sounded in his ears, and her soft tiny hand rested on his shoulder.

There was a hand upon his shoulder, but it was neither soft nor tiny; its owner being a corpulent round-headed boy, who, in consideration of the sum of one shilling per week and his food, was let out by the parish to carry medicine and messages. As there was no demand for the medicine, however, and no necessity for the messages, he usually occupied his unemployed hours — averaging fourteen a day — in abstracting peppermint drops, taking animal nourishment, and going to slee

"A lady, Sir — a lady!" whispered the boy, rousing his master with a shake. — "Tales," Chapter 6, "The Black Veil," 302.

Commentary

Extended caption adapted from the text: Then, he began to wonder when his first patient would appear, or whether he was destined, by a special dispensation of Providence, never to have any patients at all; and then, he thought about Rose again, and dropped to sleep and dreamed about her, till the tones of her sweet merry voice sounded in his ears, and her soft tiny hand rested on his shoulder. — Sketches by Boz, 358.

To fill up the first two volumes of Sketches by Boz Dickens proposed to his editor, John Macrone, (1809-37) that they use several pieces heretofore unpublished out some nine or ten pieces he had already written. In fact, so good were three of these pieces that Dickens and Macrone omitted eight of the sketches published before 1 November 1835 in order to accommodate "The Great Winglebury Duel," which Dickens had written with the Monthly Magazine in mind, and the two darker pieces written specifically for Macrone, the sketch "A Visit to Newgate" and the short story "The Black Veil." The latter is a landmark in Dickens's short fiction, as Peter Ackroyd remarks:

— the saga of a hanged man and his mother — occurred to him [after his 5 November 1835 visit to Newgate Prison], and he set to work on what is really his first proper story; it is no longer a sketch or a scene or a farcical interlude but a finished narrative. Thus we see, in miniature, the formation of the artist, reacting to the events of the life around him, using them and being used in turn. [170]

As Deborah A. Thomas in Dickens and the Short Story remarks of this journeyman effort at magazine fiction, the sketch's thin plot relies on the standard features of Regency melodrama:

A young physician, recently begun in practice, receives his first request for help on a dismal winter night. His visitor, "a singularly tall woman, dressed in deep mourning" with a face "shrouded by a thick black veil" ( 372) is a mysterious individual who implores the young doctor's assistance for a patient who cannot be seen immediately "though he is in deadly peril" and can only be seen on the following morning when he will be "beyond the reach of human aid" ( 374). The true explanation of the woman's errand is the subject of suspense throughout the tale, although, at the end, the mystery is resolved when the physician conquers his misgivings, keeps his appointment at an isolated address with the man whom he has been summoned to assist, and discovers that the latter is a criminal who has been hanged that morning and whose distraught mother has summoned medical aid in the vain hope that her son's corpse might thus be restored to life. [15-16]

Although George Cruikshank has not attempted to illustrate this story, probably because it depends so much upon an appreciation of the psychological — on the emotional and mental states of the young physician and the anguished mother — rather than on the mere externals with which Cruikshank as a caricaturist felt so comfortable, Fred Barnard has realised in his first illustration two key moments at the very beginning of the story. The initial wood-engraving, situated on the same page as the text it describes, fuses two distinct moments: the first is the boy's pointing towards the enigmatic stranger as she appears at the door (the subject of the boy's excited curiosity); and the second, when, once the doctor has ushered her in, she stands in the surgery, evoking a sense of wonder and mystery in both the young doctor and the reader. Furniss, in contrast, presents the physician still asleep and Rose as more real than the shadowy visitor.

Harry Furniss, undoubtedly having studied the illustrations of both Barnard and Cruikshank, and probably having benefitted from recent developments in the depiction of psychological states at the end of the century, actually suggests the young physician's struggling with insomnia as he thinks about proposing to Rose, a young beauty at home, and bringing her to set up housekeeping in this remote, poverty-stricken hamlet. In the Furniss treatment of this scene in The Black Veil, the doctor is still dreaming of Rose (centre) as the boy tries to nudge him awake, and the ominous outline of the veiled mother stands at the surgery door (right rear), waiting to be admitted. Barnard's fusion of the two moments in The Black Veil (see below)is less psychological than Furniss's — and both more sinister and more melodramatic. Although Thomas contends that Dickens's primary interest in the story is not the development of suspense so much as the "careful cultivation of the motif of the 'disturbed imagination'" (17) of both the doctor and his mysterious client, Furniss foregrounds the young physician, spawled asleep in his easy chair, and his messenger-boy, giving his dream of the beautiful Rose greater prominence than the obscure figure at the door of the surgery, right rear. The skull in the background (left rear), balancing the black-clad figure opposite, both implies the doctor's professional calling and prepares the reader for the story's sensational conclusion.

The Relevant Illustrations from The Household Edition (1876)

Above: Fred Barnard's somewhat melodramatic realisation of the opening scene, in which the terrified boy points at the doctor's first client, The Black Veil (1876).

Above: Fred Barnard's even more melodramatic realisation of the closing scene, in which the stupefied physician helplessly regards the prostrate mother, "My son!" rejoined the woman; and fell senseless at his feet.(1876).

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. , 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z. The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. "Tales," Chapter 6, "The Black Veil," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. 279-88.

_____. "Tales," Chapter 6, "The Black Veil," Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor & Fields edition], 431-37.

_____. "Tales," Chapter 6, "The Black Veil," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. 176-82.

_____. "Tales," Chapter 6, "The Black Veil," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1. 358-69.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. 12-15.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. , 2009.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and the Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Created 14 May 2017

Last modified 2 February 2020