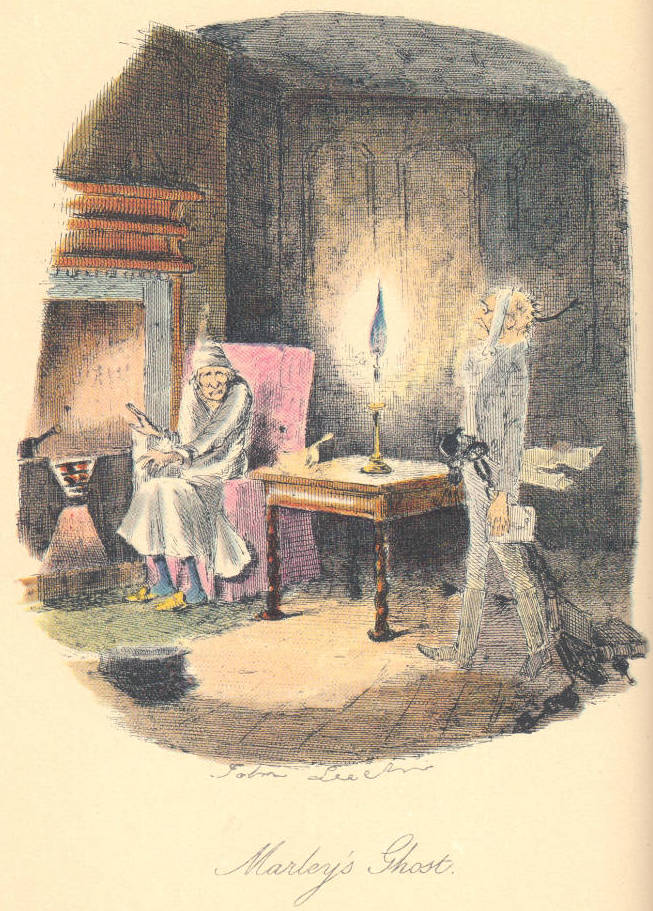

"Marley's Ghost" by Harry Furniss —

fifth illustration for "A Christmas Carol" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Realised

[Scrooge's] colour changed though, when, without a pause, it came on through the heavy door, and passed into the room before his eyes. Upon its coming in, the dying flame leaped up, as though it cried, "I know him; Marley's Ghost!" and fell again.

The same face: the very same. Marley in his pigtail, usual waistcoat, tights and boots; the tassels on the latter bristling, like his pigtail, and his coat-skirts, and the hair upon his head. The chain he drew was clasped about his middle. It was long, and wound about him like a tail; and it was made (for Scrooge observed it closely) of cash-boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers, deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel. His body was transparent, so that Scrooge, observing him, and looking through his waistcoat, could see the two buttons on his coat behind.

Scrooge had often heard it said that Marley had no bowels, but he had never believed it until now.

No, nor did he believe it even now. Though he looked the phantom through and through, and saw it standing before him; though he felt the chilling influence of its death-cold eyes; and marked the very texture of the folded kerchief bound about its head and chin, which wrapper he had not observed before: he was still incredulous, and fought against his senses. [Stave One, "Marley's Ghost," 14]

Commentary: "Leech Revised"

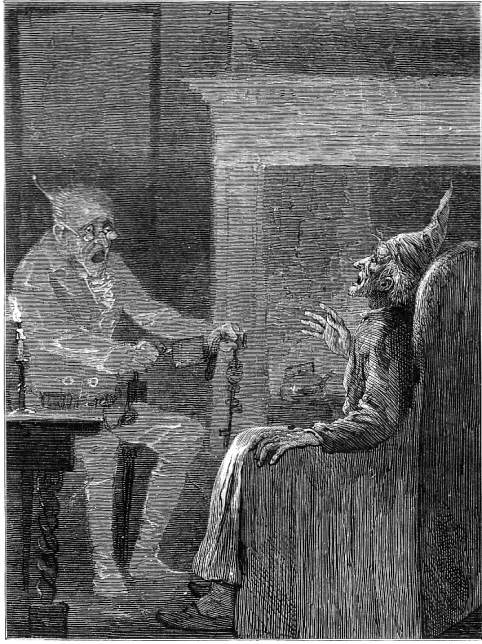

One of the most celebrated and generally recognized moments in the Dickens canon (if not all of English literature) is the scene in which his former business partner, Jacob Marley, now seven-years-dead, forces Ebenezer Scrooge to confront his own deplorable spiritual state. Every major illustrator of A Christmas Carol, including John Leech, Sol Eytinge, E. A. Abbey, Fred Barnard, Harry Furniss, and Arthur Rackham, has attempted to realise the spectral visitation in Scrooge's sitting-room. An obvious problem for the illustrator of this scene is the fact that Dickens describes the ghostly partner's body as "transparent" (14), so that the reader, like Scrooge, should be able see through the spectre to the buttons on the back his coat, and yet also be able to see his waistcoat, tights, and Hessian boots, all in the approved Regency fashion. Working within this limitation, John Leech has provided the standard image of Scrooge's confrontation with his alter-ego, and has included all the elements of furniture and costume that Dickens describes. In Leech, Eytinge, Abbey, Barnard, and Furniss, the spirit, dragging his chains, ledgers, and cashboxes, occupies the right-hand register, while Scrooge, in nightgown and nightcap, occupies the left-hand register, before the fireplace. Furniss, then, is yielding to what must have been popular expectation in realising this scene, but he must also have been aware that his readers would inevitably compare his treatment with at least Leech's and Barnard's — just as Arthur Rackham, only five years later, would have expected his readers to have compared his modelled, colourful version with those of 1843, 1878, and 1910. Whereas Rackham went out of his way to depart from past practice by reversing the positions of Scrooge and Marley, and by having Marley to appear to be on fire, Furniss borrowed heavily from Leech's version, although he minimised the fireplace (left) and gave the table straight rather than barleycane legs. The salient point of difference, then, is Scrooge's expression, which is markedly distrustful and suspicious in Furniss's illustration, rather than amazed or utterly composed.

Leech in the original edition set the terms of illustration for so many of the scenes in the novella, including the of Marley's arrival from the depths of Scrooge's subconscious and the grave, a rendition to which all subsequent illustrators have respnded. Sol Eytinge, Junior, in his 1867 Diamond Edition of The Christmas Books and in the twenty-fifth anniversary A Christmas Carol the following year reacted to Leech's composition by moving in for a closeup, first with a repentant and terrified Scrooge on his knees in "Scrooge and The Ghost" and subsequently with"Marley's Ghost", in which his focus is clearly Scrooge's remorse in the former and terror in the latter, the Ghost being transparent and seated in both. In contrast, the other illustrators realise the moment when the Ghost enters the room, when Scrooge is still trying to eat his gruel in front of a cold fire. As opposed to Eytinge's minimalist treatments and E. A. Abbey's highly atmospheric and modelled treatment of the two figures in the darkened room, Barnard's is highly dynamic as the bed-curtains and bell-pull writhe in the presence of the spirit. Viewed against this pictorial tradition, Furniss's seems very much a return to Leech's conception.

Related Illustrations from Other Editions

Upper Left: John's Leech's "Marley's Ghost"(1843); centre: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s "Scrooge and The Ghost" (1867); right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s "Marley's Ghost" (1868); lower left: E. A. Abbey's "Marley's Ghost" (1876); centre" Fred Barnard's "Marley's Ghost" (1878); right: Arthur Rackham's "'How now' said Scrooge, caustic and cold as ever 'What do you want with me?'" (1915). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Canton, Ohio: Ohio U. , 1980.

Davis, Paul. The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. New Haven: Yale U. , 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 8.

Dickens, Charles. The Christmas Books. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Il. Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1868.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Il. John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Il. Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1976.

Last modified 4 June 2013