"Sydney Carton on the Scaffold" by Harry Furniss — frontispiece for "A Tale of Two Cities" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

She kisses his lips; he kisses hers; they solemnly bless each other. The spare hand does not tremble as he releases it; nothing worse than a sweet, bright constancy is in the patient face. She goes next before him — is gone; the knitting-women count Twenty-Two.

"I am the Resurrection and the Life, saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die."

The murmuring of many voices, the upturning of many faces, the pressing on of many footsteps in the outskirts of the crowd, so that it swells forward in a mass, like one great heave of water, all flashes away. Twenty-Three.

They said of him, about the city that night, that it was the peacefullest man's face ever beheld there. Many added that he looked sublime and prophetic. . . . .

"It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known." [Book Three, Ch. 15, "The Footsteps Die Out Forever," 357-58: the picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary

Furniss prepares the reader for (or reminds the reader of) the story's dramatic climax, when Carton nobly offers himself up as a sacrifice to the blood-thirsty revolutionaries in place of the marked enemy of Madame Defarge, Charles Darnay. Even though A Tale of Two Cities initially appeared in weekly instalments in Dickens's own weekly journal All the Year Round without the benefit of illustration, Furniss had two sets of competent illustrations available as references, even if he had not seen the work of American illustrators Sol Eytinge, Juniorand John McLenan dating from the 1860s: the sixteen steel engravings in the seven monthly parts illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne and the twenty-five 1874 wood-engravings by Fred Barnard for the Household Edition — to say nothing of the Barnard study of Carton on the scaffold from 1879 for his first series of Character Sketches from Dickens (London: Cassell, Petter, and Gilpin, 1874-79), a version of which, by Toulouse Lautrec admirer John Hassall served to advertise Sir John Martin-Harvey's highly successful stage adaptation The Only Way at London's Lyceum Theatre (which debutéd on 16 February 1899, ran until 25 March 1899 with 168 performances, and was revived some ten times in London up to 1909). And issued just five years earlier than Furniss's edition, the Collins Pocket Edition offered Furniss realistic lithographs as reference points, there being two illustrations of Carton's final moments in that series. Thus, the influences at work in Furniss's frontispiece are legion.

To bolster the circulation of All the Year Roundin its opening number, 30 April 1859, Charles Dickens did more than begin with one of his own novels in weekly serialisation: he decided to experiment with simultaneous weekly numbers and monthly, illustrated parts. When the sales of the monthly instalments disappointed him, Dickens refused to blame himself for undercutting the monthly sales, and instead blamed his long-time friend and illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, for shoddy, hurried work. In fact, as in 1854, he had written the type of serialisation he detested, a slighter novel in compact weekly numbers (30 April-26 November), and had failed to provide his illustrator with adequate guidance and oversight.

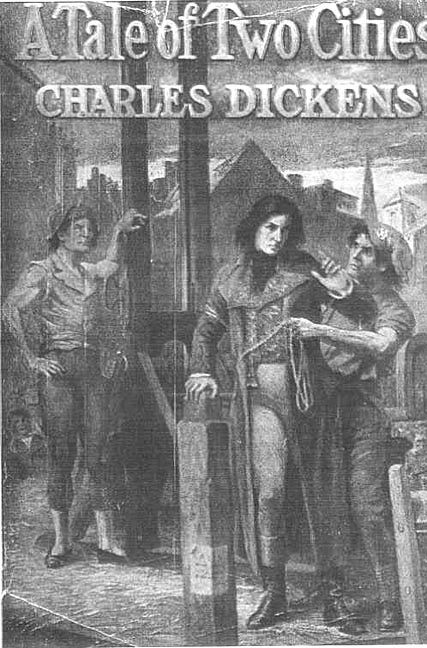

In America, there were two editions which British readers likely never saw, the work of American illustrators Sol Eytinge, Junior and John McLenan dating from the 1860s. Ticknor and Fields' slender Diamond Edition volume, published to coincide with Dickens's second visit to American shores, features an equally spare frontispiece of Sydney Carton and the Little Seamstress, a realistic rather than a sentimental rendering with a single, phlegmatic Jacobin guard and no howling mob.

In contrast, Furniss decontextualizes the solitary Carton, drawing attention to his resigned expression and hopeful glance heavenward, his only companion on the scaffold being the uniformed soldier. The vengeance and other denizens of St. Antoine, who yearn to see the blood of the St. Evremondes spilled, are nowhere in evidence, and there is no indication that the physical setting is the present Place de la Concorde, formerly Place Louis XV, but called the _Place de de la Revolution_during in the notorious Reign of Terror (the backdrop historically for the third book ofA Tale of Two Cities), which swept away some 1300 lives under the blade of the guillotine erected there in a single month of the summer of 1794. Impressionistically, Furniss gives a vague block of building on the horizon (left) for one of two magnificent buildings in the background (on either side the Rue Royale), then the Ministry of the Navy and the residence of the Duc D'Aumont. The octagonal square, gardens, moat, bridge traversing the Seine at this point (Le Pont de la Concorde, 1787-1790), and magnificent stone buildings in fact occur in none of the illustrations of Carton in the third tumbrel and on the scaffold.

Since the success of Carton's plan ultimately is contingent upon nobody's penetrating his disguise as the erstwhile Marquis St. Evremonde, from the very opening of the novel Dickens underscores the uncanny resemblance of Carton and Darnay. Hence, in illustrating the trial at the Old Bailey Furniss emphasizes the similarity in the profiles of the profligate barrister and the high-minded French emigré charged with espionage. Thus, the initial illustration, showing Carton in profile, foreshadows The Likeness in Court. Moreover, Furniss subtly draws the reader's attention to the resemblance between the two in the upper-right corner of the ornamented title-page, where Darnay faces charges in the revolutionary tribunal, and the dissolute Carton in the upper-left corner of that same page. Carton's clothing in the frontispiece is identical to that worn by Darnay in the thumbnail vignette of the French courtroom scene because Carton has, of course, appropriated his double's clothes.

In the Furniss illustration, on a gloomy day, apparently near sunset, an institutional tower — of a church or fortress prison such as the La Force — dominates the skyline, representing the repressive system that demands that its new institutions be baptized in the blood of sacrificial victims. Carton, formerly a man without purpose, now looks heavenward, as in Barnard's celebrated 1879 character study, as a uniformed guard (right) turns away from him to face what the reader presumes are the spectators, although Furniss has included none and the reader in imagination must supply the howling denizens of St. Antoine. Clearly Furniss has rejected the patient realism of the Sixties style, exemplified by Eytinge and Barnard, as well as the caricature of the earlier period of Victorian illustration as exemplified by Phiz and McLenan. What matters is the received impression of heroic self-scarifice as the reader focuses on the soldier's massive sabre and the bound wrists of the captive. Here no mob (as in Barnard's Household Edition illustration The Third Tumbrel (see below) excoriates and derides the heretofore Marquis St. Evremonde; here, no device of mass execution stands ready for its latest victim; here, no dingy patriot phlegmatically smokes his pipe as he drives the cart towards the place of execution, ignoring alike his passengers and the seething mob; here, no tender, young innocent keeps Carton company until his final moments. Without the attendant melodramatic elements, Carton stands alone, but for the soldier and the ominous horizon. Furniss's choice of this scene for the frontispiece suggests that the illustrator was well aware of his readers' general familiarity with Dickens's tale and the culminating scene of Carton's judicial murder.

Unlike illustrator A. A. Dixon five years earlier, Furniss feels no need to delineate the specifics of the scene with historical accuracy: the executioner and his assistant, the urban backdrop, and even the guillotine given such prominence by Dixon are not present. Furniss draws the reader's eye to the face and form of the courageous young Englishman, facing an unjust and arbitrary fate in order to spare his beloved Lucie's husband and ensure their future happiness across the water. There is no maudlin sentimentality in Furniss's treatment, no exploitation of the tender emotions conjured textually by the little seamstress, who appears in Eytinge's and McLenan's sequences. Whereas McLenan's visualization of Carton's final moments is embedded in the vary passage on the page of Harper's, Eytinge's and Furniss's images as frontispieces are separated from the textual passage realized as they remind the reader of the trajectory of the novel, highlighting not merely Carton's self-sacrifice but his development as a character from dissipated wastrel to romantic hero.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859) — the last Dickens's novel "Phiz" Illustrated

- Costume Notes on A Tale of Two Cities

- List of Plates by Phiz for the 1859 Monthly Instalments

- John McLenan's Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Eight Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (1874)

- A. A. Dixon's Illustrations for the Collins Pocket Edition of A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

Relevant Illustrations from earlier editions, 1859, 1867, 1874, and 1905.

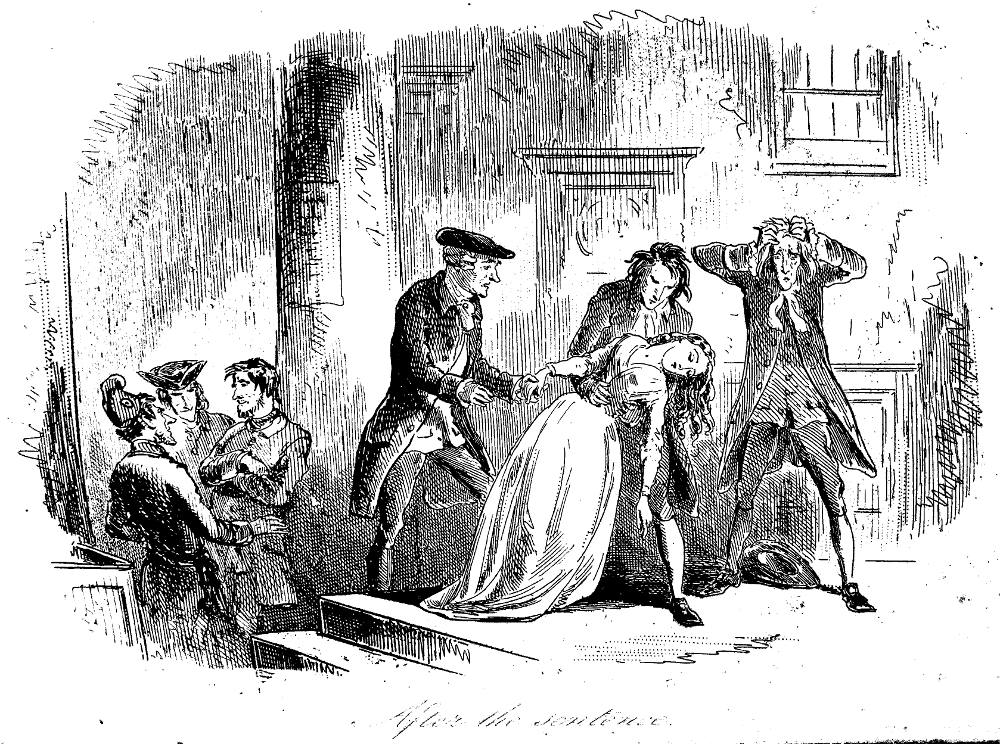

Above: Phiz's oroginal serial illustration for December 1859, <span="tcart work"="">After the Sentence.</span="tcart>

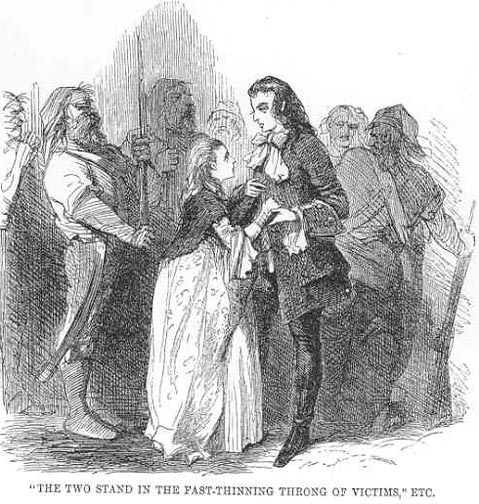

Left: John McLennan's periodical illustration of Carton on the scaffold, The two stand in the fast-thinning throng of victims; right: Sol Eytinge, Junior's frontispiece, Sydney Carton and the Seamstress (1867).

Left: Fred Barnard's The Third Tumbrel(1874); right: A. A. Dixon's front wrapper (Carton on the scaffold) (1905).

Bibliography

Barnard, Fred. A Series of Character Sketches from Charles Dickens [Series One: Alfred Jingle, Mrs. Gamp, Bill Sikes, Little Dorrit, Samuel Pickwick, and Sidney Carton]. London: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co., 1880 [portfolio].

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1988.

Bolton, H. Phili "A Tale of Two Cities." Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987, 395-412.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. All the Year Round. 30 April through 26 November 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. 7 May through 3 December 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities andGreat Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Created 28 October 2013

Last modified 5 January 2020