"Oliver and His Mother's Portrait" by Harry Furniss — frontispiece for Dickens's "Adventures of Oliver Twist" (1910) (original) (raw)

Context of the Illustration of the Dozing Oliver

Gradually, [Oliver, translated to the housekeeper's room downstairs] fell into that deep tranquil sleep which ease from recent suffering alone imparts; that calm and peaceful rest which it is pain to wake from. Who, if this were death, would be roused again to all the struggles and turmoils of life; to all its cares for the present; its anxieties for the future; more than all, its weary recollections of the past!

It had been bright day, for hours, when Oliver opened his eyes; he felt cheerful and happy. The crisis of the disease was safely past. He belonged to the world again.

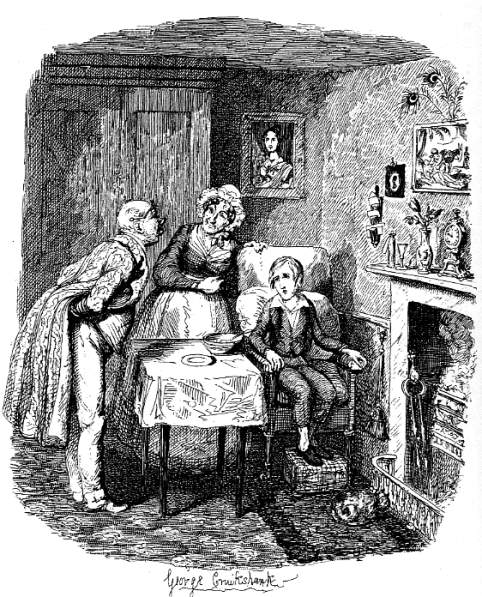

In three days' time he was able to sit in an easy-chair, well propped up with pillows; and, as he was still too weak to walk, Mrs. Bedwin had him carried downstairs into the little housekeeper's room, which belonged to her. Having him set, here, by the fire-side, the good old lady sat herself down too; and, being in a state of considerable delight at seeing him so much better, forthwith began to cry most violently. . . . .[80]

"Are you fond of pictures, dear?"inquired the old lady, seeing that Oliver had fixed his eyes, most intently, on a portrait which hung against the wall; just opposite his chair.

"I don't quite know, ma'am," said Oliver, without taking his eyes from the canvas; "I have seen so few that I hardly know. What a beautiful, mild face that lady's is!"

"Ah!"said the old lady, "painters always make ladies out prettier than they are, or they wouldn't get any custom, child. The man that invented the machine for taking likenesses might have known that would never succeed; it's a deal too honest. A deal," said the old lady, laughing very heartily at her own acuteness.

"Is — is that a likeness, ma'am?"said Oliver.

"Yes,"said the old lady, looking up for a moment from the broth; "that's a portrait."

"Whose, ma'am?"asked Oliver.

"Why, really, my dear, I don't know,"answered the old lady in a good-humoured manner. "It's not a likeness of anybody that you or I know, I expect. It seems to strike your fancy, dear."

"It is so pretty," replied Oliver. [Chapter 12, "In which Oliver is taken better care of than he ever was before. And in which the narrative reverts to the merry old gentleman and his youthful friends," 81]

Commentary

Whereas Dickens begins the novel with the death of Oliver's mother in the workhouse a considerable distance north of London, Furniss's initial lithograph from a pen-and-ink wash drawing focuses on the boy's comfortably dozing in an easy chair in the housekeeper's room of Mr. Brownlow's house in Pentonville, north London. Recovering from an acute fever, Oliver finds himself in a comfortable easy-chair and presented with a bowl of hot broth; above him is the oil-portrait of a fashionably dressed young woman of about twenty years of age. In the frontispiece, Furniss combines the passage describes Oliver's fitful slumber over a number of days upstairs with his questioning Mrs. Bedlow about the portrait in her room downstairs. In the frontispiece, the young lady (in fact, Oliver's mother) seems to be looking out of the frame and directly at the reader. The placement and subject matter of this illustration reflect Furniss's knowledge of the plot of the entire novel, a knowledge that the original serial illustrator, George Cruikshank probably lacked when he bagan the commission for Bentley's Miscellany in January 1837.

Like the Household Edition illustrator James Mahoney in 1871, Furniss in 1910 had the definite advantage of having read the entire novel in advance, as well as of having seen Mahoney's twenty-eight wood-engravingsfor the novel and the twenty-four steel-engravings from 1837-38 by Dickens's original illustrator. For his program of "34 original illustrations" announced on the title-page, Furniss rarely elected merely to emulate past practice for the first half of volume III of the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910). Although the influence of Cruikshank predominates, Furniss is often "original" in his treatment of Cruikshank's subjects, as in his re-thinking and reconfiguration of Oliver recovering from fever (see below), Cruikshank's serial illustration for August 1837, a drawing made expressly at Dickens's behest to make plain Oliver's much-improved circumstances ordained by a beneficent Providence. The Furniss caption makes the identity of the young woman perfectly clear, but (unlike the majority of Furnnis's illustrations) does not point through a quotation or extended caption to a specific moment in the text. On the other hand, in Cruikshank's illustration the portrait's initial relationship to the boy is not clear at all, but the juxtaposition of the plate and the text, and the illustration's placement within the book, point to a highly specific passage. Dickens first draws the reader's attention to the likeness between the portrait in Mr. Brownlow's Pentonville home and the recently arrived "Tom White" in Chapter 12, preparing the reader for the whole series of coincidences involving Mr. Brownlow and Rose Maylie in the novel's "inheritance" plot.

Weeks after his release from detention and the sentence of three months' hard labour after the bookstall owner's testimony has exonerated him, Oliver, weak but recovered from the fever, awakens at Mr. Brownlow's home in Pentonville, north London. Carried downstairs to the room of the grandmotherly housekeeper, Mrs. Bedwin, Oliver pays special attention to a portrait of a young lady in her room. Cruikshank's treatment of the subject of the poor boy taken in and nursed back to health by the elderly bachelor and his kindly housekeeper, Mrs. Bedwin, is both theatrical and narrative; that is, the Regency illustrator has included all the elements that Dickens describes, including the feverish boy in his chair, Mr. Brownlow in his embroidered dressing-gown, such theatrical properties as the table, fireplace, and wardrobe (producing a rather crowded effect), and, above Oliver, the small portrait, a taken-from-the-life study which is complemented by the ornately framed oil painting above the mantelpiece of a suitable biblical analogue, the kindness of the Good Samaritan in Christ's New Testament parable in "The Gospel According to St. Luke" (10: 25-37).

Conspicuous on the wall immediately above and behind Oliver is yet another inset picture, a portrait that proves to be that of Oliver's mother, about whom in his delirium he has dreamed, as if she were his guardian angel. This scene of Oliver's charitable and even loving adults contrasts previous scenes, including that of the "false" Samaritan, the master-thief Fagin; again, as in Oliver introduced to the respectable Old Gentleman, Cruikshank has positioned Oliver to the right and his saviours to the left, Mrs. Bedwin occupying the central position taken by the Artful Dodger in the earlier illustration. Despite the effectiveness of these juxtapositions, the reader has to sort through the crowded details to study the likeness of the tiny portrait and the sickly Oliver.

The Good Samaritan, by the way, was something of a favourite subject with Victorian painters such asGeorge Frederic Watts (1852) and John Everett Millais (1863). Indeed, the parable seems to have been a commonplace for philanthropic activity among the upper-middle and upper classes, as in the low relief sculpture for Sarah Elizabeth Wardroper by George Tinworth (1893-94).

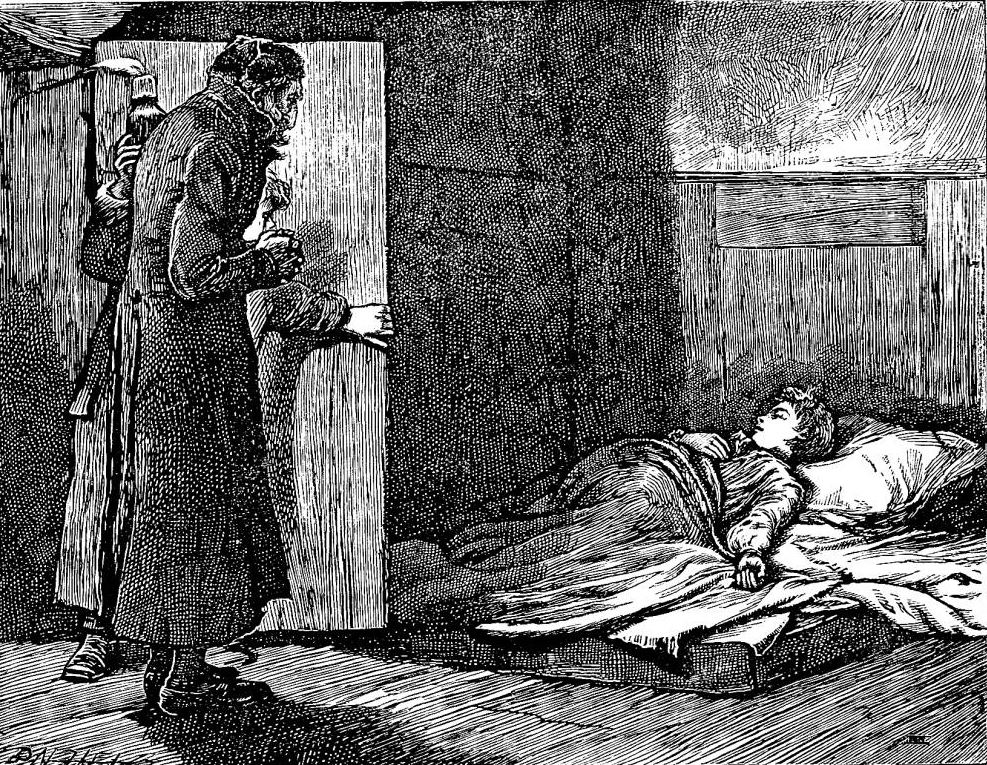

Although in composing the series for the 1871 Household Edition Mahoney had the advantage of being able to study Cruikshank's plates assiduously well in advance of his receiving the Chapman and Hall commission for the first volume in the new edition, he rarely pays homage to Cruikshank's original conceptions, which are often caricatural rather than examples of social realism. Instead, for example, of depicting the tenderness of Mr. Brownlow and Mrs. Bedwin in caring for Oliver, Mahoney elects to show a parallel scene of the boy's ill-treatment by Monks and Fain once they have recaptured Oliver, The boy was lying, fast asleep, on a rude bed upon the floor (see below), in Chapter 19, "In Which a Notable Plan is Discussed and Determined On."

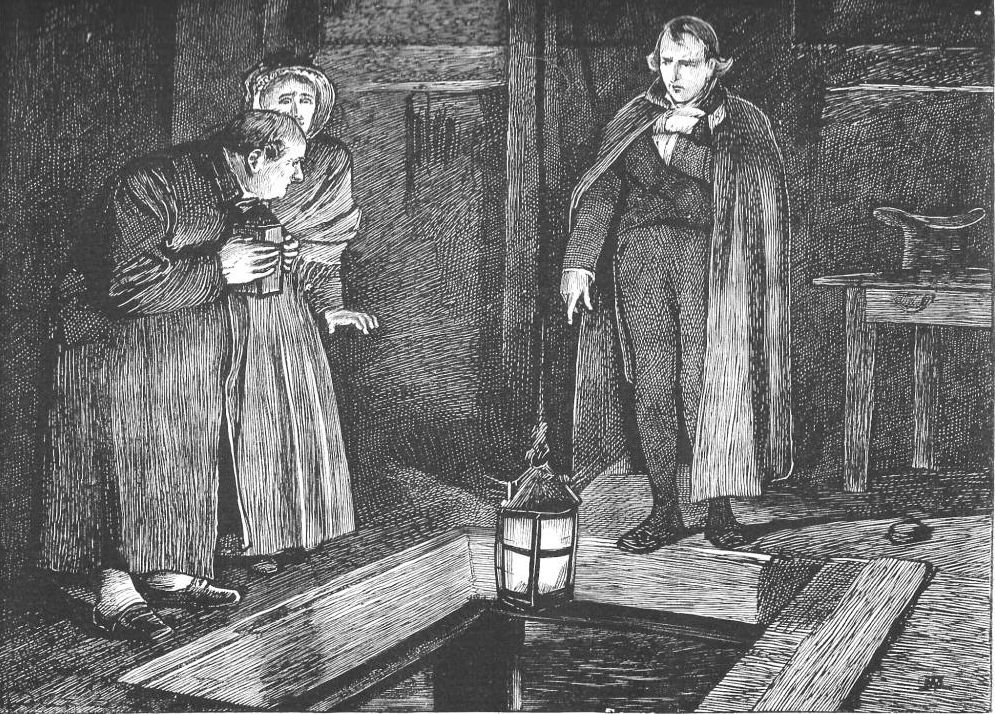

Rejecting the obvious sentimentality and detailism of the Cruikshank original, Furniss dispenses with the other embedded painting, the furnishings, and the attendants in order to focus on the irony of Oliver's dozing beneath the portrait that turns out to be that of the mother whom he never knew but whom he has sensed as an abiding presence. As opposed to the 1846 frontispiece by Cruikshank, which merely alludes to the first of Oliver's "adventures," when he asks the master of the workhouse for more gruel, the Furniss frontispiece refers to the overarching "lost heir" plot in which Providence directs the boy unwittingly to connect with his mother's sister and his father's best friend. Mahoney's 1871 frontispiece (see below) likewise directs the reader to the "lost heir" plot through depicting Monks's attempting to destroy the evidence of Oliver's true identity.

Relevant Illustrations from the serial edition (1837) and Household Edition (1910)

Left: Cruikshank's Oliver recovering from fever (1837). Right: Cruikshank's frontispiece, Oliver's asking for more (1837, 1846).

Above: Mahoney's 1871 Household Edition engraving of the sleeping Oliver observed by Fagin and Monks, The boy was lying, fast asleep, on a rude bed upon the floor..

Above: Mahoney's 1871 Household Edition frontispiece focusses the reader's attention on the secret of Oliver's birth and the true identity of his workhouse mother,The Evidence Destroyed..

Bibliography

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1838; rpt. with revisions 1846.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

_____.The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. I (1820-1839).

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. I, Book 2, Chapter 3.

Vann, J. Don. "Oliver Twist." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985, 62-63.

Created 31 December 2014

Last modified 17 February 2020