"The Dodger's Toilet" by Harry Furniss — twelfth illustration for Dickens's "Adventures of Oliver Twist" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

"Look here!" said the Dodger, drawing forth a handful of shillings and halfpence. "Here's a jolly life! What's the odds where it comes from? Here, catch hold; there's plenty more where they were took from. You won't, won't you? Oh, you precious flat!"

"It's naughty, ain't it, Oliver?" inquired Charley Bates. "He'll come to be scragged, won't he?"

"I don't know what that means," replied Oliver.

"Something in this way, old feller," said Charley. As he said it, Master Bates caught up an end of his neckerchief; and, holding it erect in the air, dropped his head on his shoulder, and jerked a curious sound through his teeth; thereby indicating, by a lively pantomimic representation, that scragging and hanging were one and the same thing.

"That's what it means," said Charley. "Look how he stares, Jack!" [Chapter 18, "How Oliver passed his time in the improving society of his reputable friends," 134]

The Charles Dickens Library Edition’s Long Caption

Master Bates gives a lively pantomimic representation of hanging. "Look how he stares, Jack! I never did see such prime company as that 'ere boy.” [134]

Commentary

Dickens's original illustrator, George Cruikshank responded to Dickens's November 1837 suggestion for an illustration with an allusion to hanging even street-boys for petty theft in Master Bates Explains a Professional Technicality. The picture shows Oliver's being re-indoctrinated into Fagin's criminal ethos through the companionship of the hardened thieves Charles Bates and Jack Dawkins ("The Artful Dodger") in Part 9, December 1837, in Bentley's Miscellany. By the time that Furniss portrayed this once-cautionary scene, even transportation had ceased, and the harsh 18th-century code of justice much ameliorated.

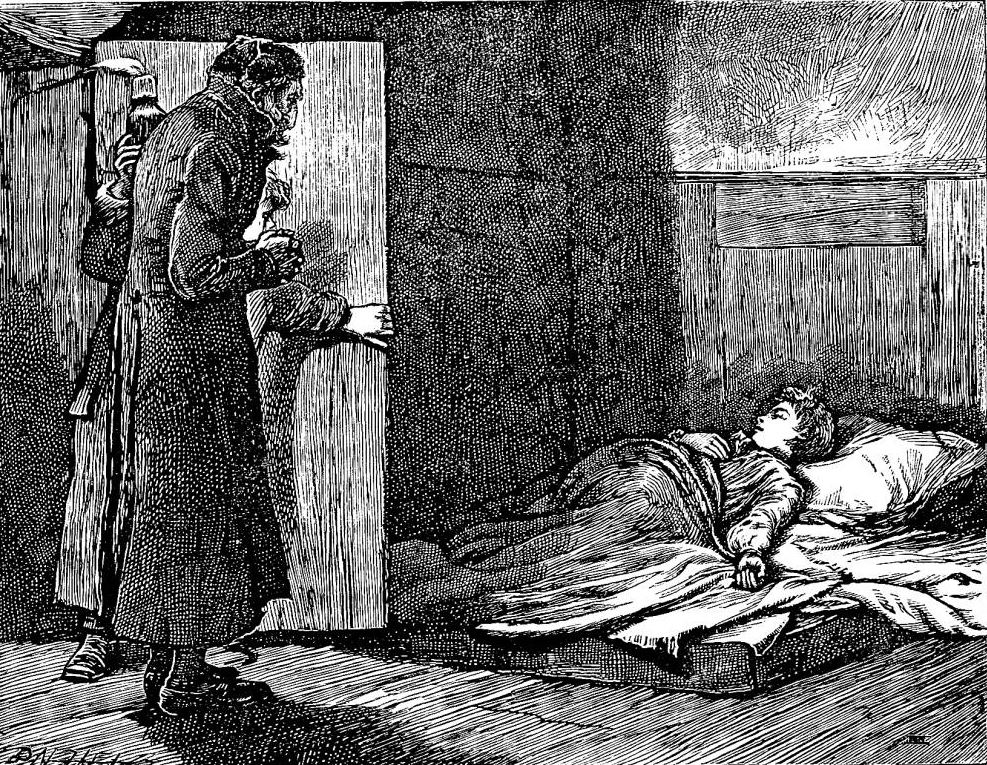

There is no comparable scene of youthful horseplay in the 1871 Household Edition volume because realist James Mahoney takes this opportunity to prepare the reader for Fagin's lending Oliver to housebreaker Bill Sikes to assist in the ill-fated robbery at Chertsey in The boy was lying, fast asleep, on a rude bed upon the floor, in Chapter 19, "In Which a Notable Plan is Discussed and Determined On."

Furniss has modelled his illustration of Oliver's reprogramming, then, directly on the Cruikshank original. Despite his being the resident clown of the gang, Charley Bates lives very much in the shadow of his more famous friend, The Artful Dodger, whose wit and personality are markedly more brazen. The November 1837 letter in which Dickens arranges to meet his illustrator to "settle the Illustration" (Letters, I: 329) sheds little light on why the author and artist settled upon this "gallows humour" scene with "Master Bates." However, one may speculate that, having given Jack Dawkins and Fagin centre stage in both Oliver introduced to the respectable Old Gentleman andOliver amazed at the Dodger's mode of going to work (June and July 1837), author and illustrator wanted to showcase the waggish Charley Bates. Certainly, he has not continued to enjoy the celebrity in which his partner-in-crime has basked (thanks in part to Lionel Bart's 1969 musical adapted for the cinema, Oliver!. As the plot thickens and the gang plans to use Oliver as its vehicle for breaking into the manor house at Chertsey, Surrey, the scene provides welcome and necessary comic relief. As Monroe Engle remarks, the Dodger's later "bravado before the court [at his hearing regarding transportation], for example, is moving because it is in the face of heavy consequences. The point is not only that the criminals are threatened by death, but that they are all of them, even the most hardened, aware of the imminence of this threat almost all the time" (106).

Thus, when Charley mimics being hanged by the neck until dead, the usual sentence for even the most trivial of crimes against property prior to the reforms of the 1830s, he is not merely laughing in the face of death, but ridiculing a heartless system. In his horseplay he becomes Dickens's spokesperson for reform. The tom foolery, of course, is Dickens's strategy for creating an ambivalent response in his middle-class readers, who, despite their deploring crimes against property, cannot help but laugh at Charley's antics, in both text and illustration. To fully enjoy Charley's act as the class clown we must become members of the class.

Although Furniss at the turn of the century may not have been acutely aware of the draconian laws which menace Charley and the Dodger on their every expedition, and was not then able to peruse the Dickens-Cruikshank correspondence regarding the choice of this subject, he certainly could have evaluated the strengths and demerits of Cruikshank's original steel engraving. In consequence, the present illustration represents both Furniss's homage to the earlier illustrator and a critical re-thinking. In the original, behind Charley, simulating the noose, is a very stout wooden door which represents enforced isolation. Welcoming any company whatsoever, Oliver gladly becomes the Dodger's bootblack, in thieves' cant, "japanning his trotter-cases" (132). In Furniss's impressionistic revision, the stout door of Oliver's cell all but disappears as the illustrator presents the young thieves not as Fagin's agents but as boozy puppets, and Oliver, now to the side (rather than sandwiched in between them, as in Cruikshank's plate), as the only undistorted human form in the scene. The juxtaposition makes Oliver the normative observer and Charley the entertainer. Under the influence of the large tankards of London ale, the pickpockets jeer at capital punishment, even though Charley's parodying of hanging is not likely to induce Oliver to become an active member of the gang — even though, in fact, that is exactly what he is about to become. So effective is Charley as a comedian that in Furniss's illustration Oliver appears to be highly entertained, whereas in the Cruikshank original he looks somewhat alarmed at the grim fate that awaits these youthful criminals.

During the period in which Dickens's Newgate Novel is set, criminals were hanged for offences other than murder: in 1820, moreover, a year when nobody was hanged for homicide, 29 were hanged at Newgate for such lesser crimes as uttering forged notes (twelve instances) and for theft (twelve for robbery or burglary, and five for highway robbery). Charley Bates was quite right, then, about the fate that would probably attend his following the "trade." Ironically, were he to be tried and found guilty of anything other than theft, rape, murder, arson, or forgery, he would most certainly be transported and not hanged until well into the century. Typically in the eighteenth century, crimes against property merited hanging: there were roughly two hundred such crimes, that number only being reduced to just over one hundred in 1823 by the Tory administration ofSir Robert Peel. If the period of the main action of the novel is "Post-Reform Bill," so to speak, Charley's chances of escaping the noose would increase, as, seven years after Peel's initiative, the Liberal administration of Lord John Russell abolished the death sentence for horse stealing and housebreaking. One must assume that, if the story occurs in the early 1830s, Bill Sikes would have hanged as a murderer rather than a mere burglar, but Fagin's hanging for his crimes against property, although on a massive scale, would be less likely — we must assume, therefore, that he is condemned to death for "criminal conspiracy" in the murder of Nancy.

Illustrations from Six Editions of Oliver Twist, 1837-1890

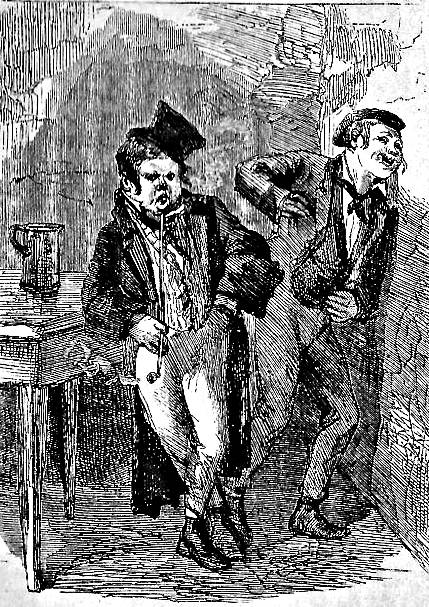

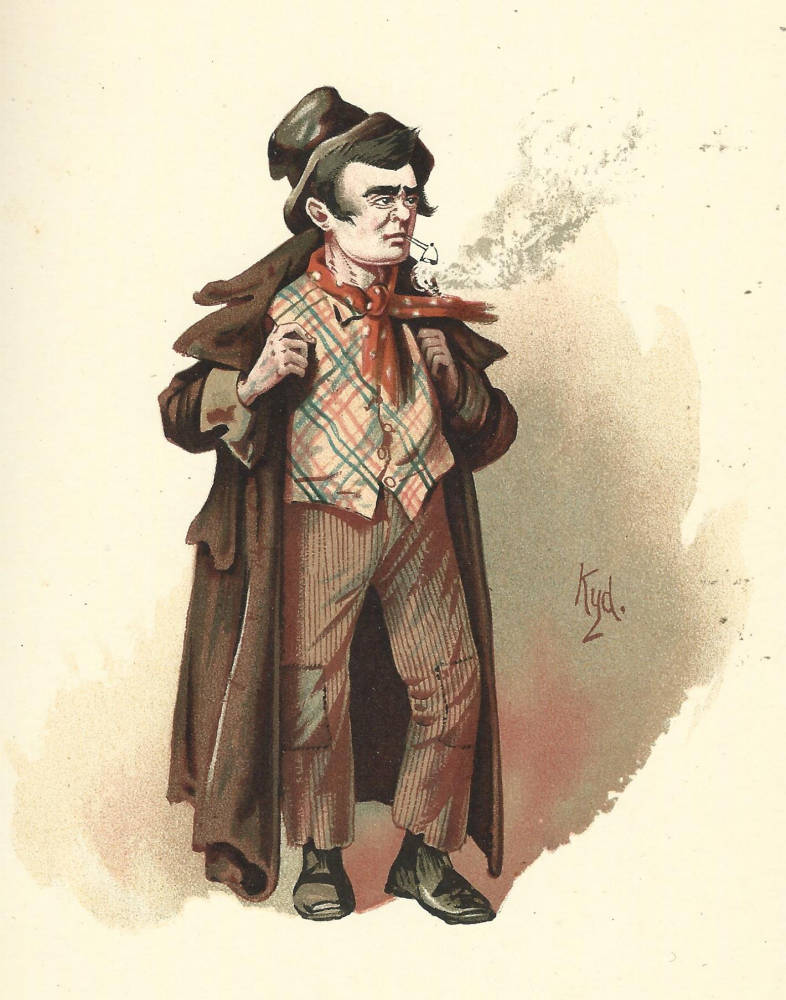

Left: George Cruikshank's original version of Master Bates Explains a Professional Technicality (Dec. 1837). Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's The Artful Dodger and Charley Bates (1867). Right: Kyd's 1890 realisation of the self-confident Dodger in The Artful Dodger.

Above: Mahoney's 1871 realisation of Oliver's incarceration in the gang's White Chapel hideout, The boy was lying, fast asleep, on a rude bed upon the floor.

Bibliography

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1838; rpt. with revisions 1846.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

_____.The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. I (1820-1839).

Engles, Monroe. "Oliver Twist: A Purposeful Plot." Readings on "Oliver Twist." Ed. Jill Karson. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven, 2001, 101-8.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. I, Book 2, Chapter 3.

Kyd (Clayton J. Clarke). Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Vann, J. Don. "Oliver Twist." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985, 62-63.

Created 30 January 2015

Last modified 14 February 2020