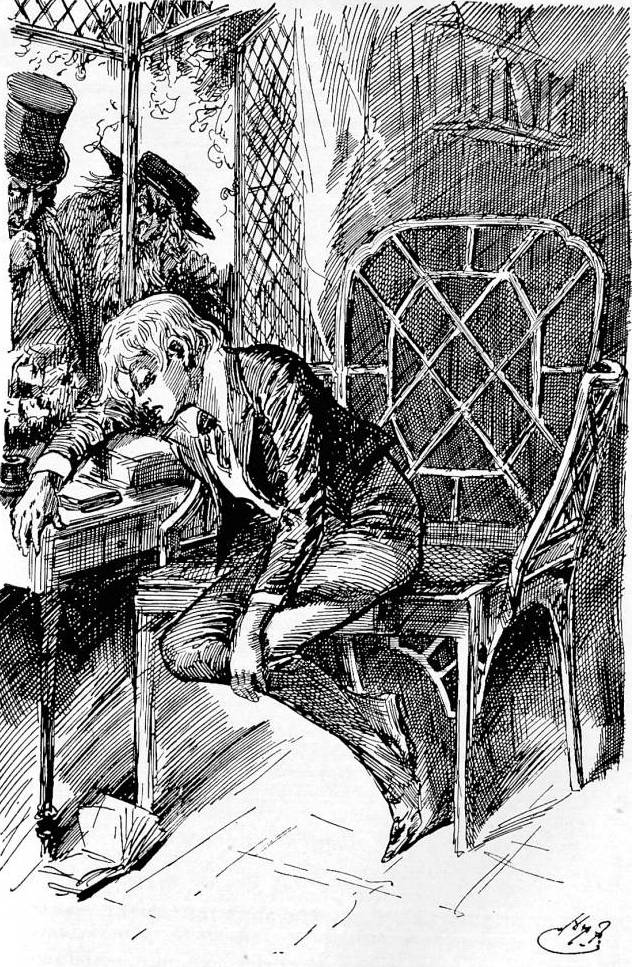

"The wounded Oliver smiles in his Sleep" by Harry Furniss — twentieth illustration for Dickens's "Adventures of Oliver Twist" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

Stepping before them, he looked into the room. Motioning them to advance, he closed the door when they had entered; and gently drew back the curtains of the bed. Upon it, in lieu of the dogged, black-visaged ruffian they had expected to behold, there lay a mere child: worn with pain and exhaustion, and sunk into a deep sleep. His wounded arm, bound and splintered up, was crossed upon his breast; his head reclined upon the other arm, which was half hidden by his long hair, as it streamed over the pillow.

The honest gentleman held the curtain in his hand, and looked on, for a minute or so, in silence. Whilst he was watching the patient thus, the younger lady glided softly past, and seating herself in a chair by the bedside, gathered Oliver's hair from his face. As she stooped over him, her tears fell upon his forehead.

The boy stirred, and smiled in his sleep, as though these marks of pity and compassion had awakened some pleasant dream of a love and affection he had never known. Thus, a strain of gentle music, or the rippling of water in a silent place, or the odour of a flower, or the mention of a familiar word, will sometimes call up sudden dim remembrances of scenes that never were, in this life; which vanish like a breath; which some brief memory of a happier existence, long gone by, would seem to have awakened; which no voluntary exertion of the mind can ever recall. [Chapter 30, "Relates what Oliver's New Visitors Thought of Him," 217]

The Charles Dickens Library Edition’s Long Caption

The younger lady glided softly past, and seating herself in a chair by the bedside, gathered Oliver's hair from his face. As she stooped over him, her tears fell upon his forehead. [217]

Commentary

Furniss, the last great Victorian illustrator of Dickens's second novel, depicts the sleeping Oliver watched over by the solicitous Dr. Losberne and the tender Rose Maylie (unbeknownst to him, his aunt).The illustrator has chosen to create a purely sentimental scene rather than follow George Cruikshank, the novel's original illustrator, who emphasized suspense and comedy. Whereas in the original serial had tended to focus on more dramatic and humorous incidents, such as Oliver's being interviewed by the obtuse police detectives Blathers and Duff, in the first volume of Household Edition, James Mahoney had offered a sentimental moment for realisation that provided Furniss with a precedent for depicting other, more sentimental moments at this juncture. However, Furniss's lithograph does not, like the original serial steel-engraving for this chapter, immediately lead readers to speculate about whether, once he regains consciousness, Oliver will identify the notorious Bill Sikes as the chief culprit — and whether the police officers will uncover the fact that Oliver was himself involved in the attempted burglary. The present illustration represents Furniss's very different reaction to both the original illustration and Dickens's text, as he eliminates (at least for the moment) any speculation about how much involving the robbery Oliver will choose to disclose to the minions of the law. Moreover, Furniss causes the reader to reflect upon the providential nature of Oliver's "progress." Archly, too, Furniss alludes to this idyllic bedside scene in its sinister parallel, the very next illustration, Monks and Fagin Watching Oliver Asleep:

Above: The companion illustrations of Oliver watched in his sleep by very different observers with very different intentions: The wounded Oliver smiles in his Sleep, and Monks and Fagin watching Oliver sleep. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

In the present plate, having dragged himself to the Maylies' front door (after being dumped in a ditch by the fleeing Sikes), Oliver, near death, is nursed back to health by the kindly Rose Maylie, her adopted mother, and the local physician, all three of whom the illustrator of the 1910 includes. Providentially Oliver is tended by his mother's sister, having by those same powers of Providence already been befriended by his father's best friend from youth, Mr. Brownlow. Although Cruikshank took obvious delight in depicting Oliver's reception by the Maylies' comic suspicious servants in Oliver at Mrs. Maylie's door (Part 13, April 1838), and his interrogation by the rather thick-headed police officers Blathers and Duff in Oliver waited on by the Bow Street Runners (see below). For Chapter 31 in the first volume of the Household Edition, Mahoney had adopted quite a different tactic by emphasizing the harmonious tranquility into which Oliver's life now flows at the Maylies' in When it became quite dark, and they returned home, the young lady would sit down to the piano, and play some pleasant airs, in which Harry and Rose present a cultured and sympathetic home-life wholly new to the ex-parish boy and quondam pickpocket-in-training. However, reverting to the original Cruikshank scene but significantly adjusting it, the fin de siecle artist dwells upon providential nature of Oliver's being cared for by his dead mother's younger sister, resident in a house that Oliver's criminal associates had sought to rob. This ironic nature of the improbable reunion Furniss underscores by drawing the viewer's eye towards the heads of Oliver and Rose so that the reader notes similarity in hair and profile of the boy and his aunt. In short, in eliminating the character comedy, it is as if Furniss expected that readers would already be familiar with Cruikshank's steel engravings, and therefore avoided merely repeating those earlier realisations, even as he continues Oliver's "progress" out of the underworld and back into his proper station in English society.

For the reader unacquainted with the story's trajectory, a proleptic reading of the passage in the text in the Charles Dickens Library Edition would suggest that Oliver once again will suffer a near death experience, if indeed he does not die of his wound and exposure. However, by the time that readers arrive at the Furniss illustration of that textual moment, they are aware that Oliver has been accepted into the Maylie mansion as a child in need of medical assistance rather than a thief who has been wounded in the commission of a robbery. Providence has decreed that he should be embraced his mother's sister, Rose, and her adoptive family, the Maylies. Thus, the Furniss illustration is not merely sentimental or even coincidental, but providential. In contrast to the original Cruikshank illustration, this 1910 revision lacks the humour afforded by the Bow Street Runners, figures whose self-important foolishness anticipates the utter ineptitude of early film-maker Mack Sennet's Keystone Cops (1912-1917).

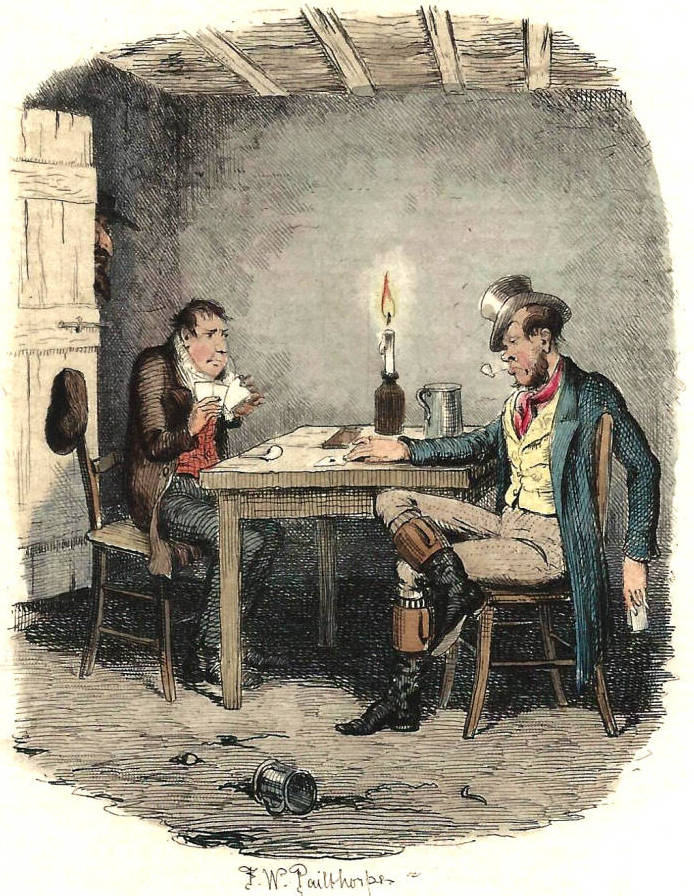

Since either the series editor, J. A. Hammerton, or Furniss himself has positioned the illustration for Chapter 30 well into Chapter 31, "Involves a Critical Position," facing p. 225, by the time that the reader has encountered the illustration the reader knows that Oliver will make a full recovery, for on p. 225 in Chapter 31 "Mssrs. Blathers and Duff, attended by the native [i. e., local] constable" (225) are interrogating Oliver, as in the 1838 Cruikshank illustration, so that in the original Dickens's satire of the ineptitude of the Bow Street Runners (the pre-Scotland Yard London police force founded by magistrate Henry Fielding) foils the sweet sentimentality of the Oliver's receiving appropriate care from the Maylies and their servants. Furniss underscores the facial similarities between Rose Maylie and Oliver, both of whom he has deliberately drawn in profile. The fourth figure in the scene, just behind the physician, is Mrs. Maylie, an elderly, upper-middle-class lady with a look of deep concern which reveals that she, too, is a female Samaritan figure like Mr. Brownlow's housekeeper, Mrs. Bedwin, earlier in the story. In contrast, Furniss's contemporary, J. Clayton Clarke depicts only the stronger, more threatening, or more amusing characters and scenes, even as contemporary comic artist F. W. Pailthorpe in his 1886 sequence had avoided this tender moment entirely, dwelling instead upon the fashionable lock-picker Toby Crackit. As we shall shortly see, Furniss is also using the tranquil scene of the boy asleep and watched by kindly figures as a contrast to the scene in which Fagin and Monks critically observe Oliver asleep one afternoon.

Illustrations from Editions of Oliver Twist, 1837-1910

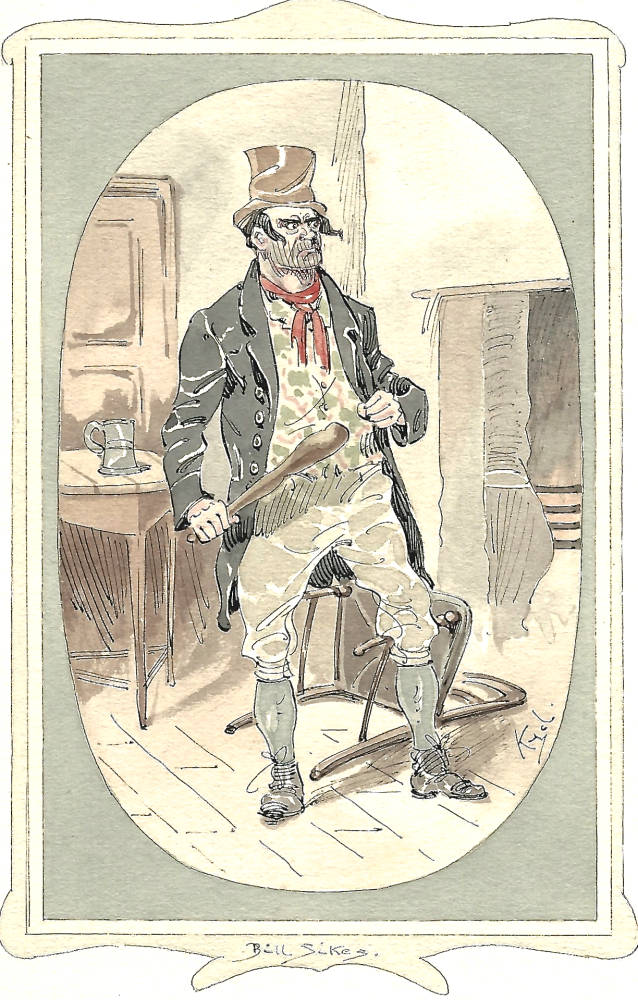

Left: Cruikshank's Oliver waited on by the Bow Street Runners (Part 14, May 1838). Centre: Kyd's depiction of the violent Bill Sikes. Right: Pailthorpe's Mr. Crackit's 'good natur' (1886).

Above: Mahoney's 1871 engraving of Oliver's tranquil life at the Maylies', When it became quite dark, and they returned home, the young lady would sit down to the piano, and play some pleasant air.

Bibliography

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1838; rpt. with revisions 1846.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

_____.The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. I (1820-1839).

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. I, Book 2, Chapter 3.

Jordan, John O. "The Purloined Hankerchief." Chapter 3, "A Critical Selection." Readings on Charles Dickens "Oliver Twist.". Greenhaven Press Literary Companion to British Literature. Originally in Dickens Studies Annual, 1989. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven, 2001, 167-83.

Kyd (Clayton J. Clarke). Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Pailthorpe, Frderick W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Vann, J. Don. "Oliver Twist." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985, 62-63.

Created 23 February 2015

Last modified 15 February 2020