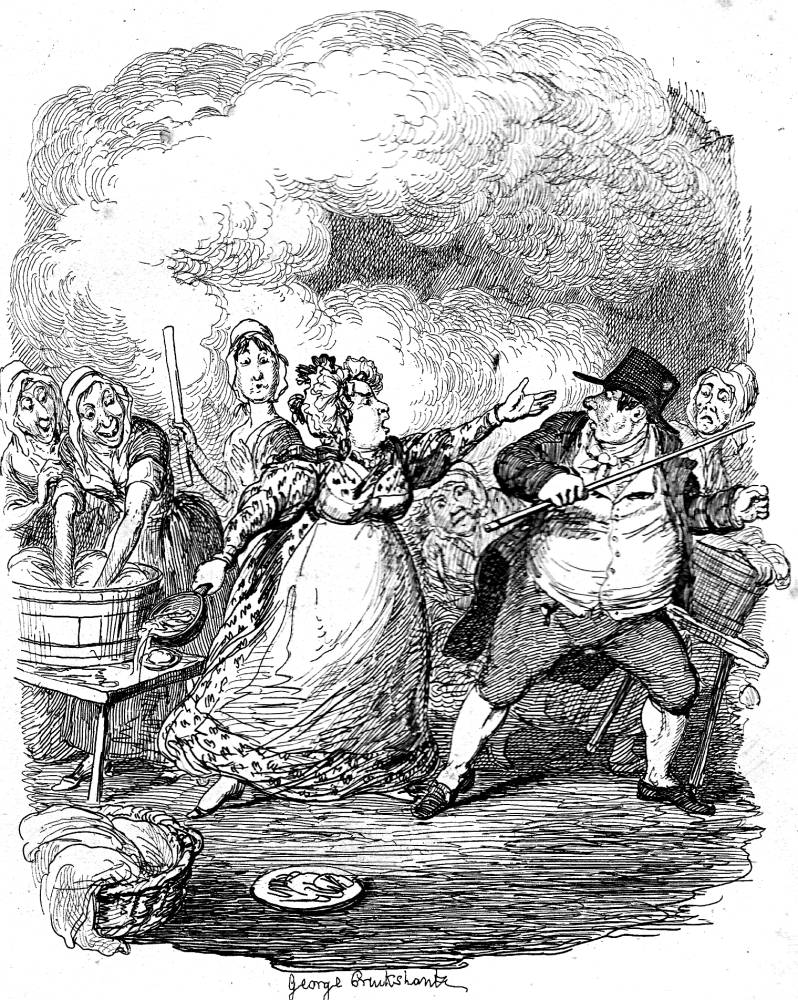

"Mrs. Bumble turns Mr. Bumble out" by Harry Furniss — twenty-second illustration for Dickens's "Adventures of Oliver Twist" (1910) (original) (raw)

Context of the Illustration

"My dear," said Mr. Bumble, "I didn’t know you were here."

"Didn't know I was here!" repeated Mrs. Bumble. "What do you do here?"

"I thought they were talking rather too much to be doing their work properly, my dear," replied Mr. Bumble: glancing distractedly at a couple of old women at the wash-tub, who were comparing notes of admiration at the workhouse-master's humility.

"You thought — they were talking too much?" said Mrs. Bumble. "What business is it of yours?"

"Why, my dear —" urged Mr. Bumble submissively.

"What business is it of yours?" demanded Mrs. Bumble, again.

"It's very true, you're matron here, my dear," submitted Mr. Bumble; "but I thought you mightn't be in the way just then."

"I’ll tell you what, Mr. Bumble," returned his lady. "We don't want any of your interference. You're a great deal too fond of poking your nose into things that don't concern you, making everybody in the house laugh, the moment your back is turned, and making yourself look like a fool every hour in the day.

"Be off; come!"

Mr. Bumble, seeing with excruciating feelings, the delight of the two old paupers, who were tittering together most rapturously, hesitated for an instant. Mrs. Bumble, whose patience brooked no delay, caught up a bowl of soap-suds, and motioning him towards the door, ordered him instantly to depart, on pain of receiving the contents upon his portly person.

What could Mr. Bumble do? He looked dejectedly round, and slunk away; and, as he reached the door, the titterings of the paupers broke into a shrill chuckle of irrepressible delight. It wanted but this. He was degraded in their eyes; he had lost caste and station before the very paupers; he had fallen from all the height and pomp of beadleship, to the lowest depth of the most snubbed hen-peckery. [Chapter 37, "In Which the Reader May Perceive a Contrast Not Uncommon in Matrimonial Cases," 274-275: wording of the original caption for this illustration emphasized]

Commentary: Neither LOved, Honoured, or Obeyed

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's "Mrs. Corney and Mr. Bumble". Right: George Cruikshank's original serial illustration "Mr. Bumble degraded in the eyes of the Paupers" (1838).

Furniss seems to have based his illustration upon a steel engraving by Dickens's original illustrator, George Cruikshank, that appeared in the July 1838 Bentley's Miscellany — Mr. Bumble degraded in the eyes of the Paupers (see above). Two months after their marriage, Bumble is chagrined to discover that the former Mrs. Corney is not prepared to follow his commands meekly, and that he is husband in name only, with no authority whatsoever over his wife. The scene of the contretemps is the feminine sphere of her workplace, the laundry-room of the parish workhouse, and the amused spectators of the uneven combat are the pauper women who are the Matron's subordinates and supporters. Stripped of parochial authority and now plain "Mr." Bumble, he finds himself neither, loved, honoured, or obeyed by his wife, who has suddenly become self-assertive and even obstinate. Dickens regards the temporary romance of workhouse matron Mrs. Corney and parish beadle Mr. Bumble not merely as ridiculous, but as setting the stage for their nemesis, just as the clandestine affair between the Sowerberrys' maid, Charlotte, and the charity boy apprentice Noah Claypole will shortly develop into mutual torment and antipathy that justly rewards them for their ill-treatment of Oliver. Thus, the scene of Bumble's inevitable humiliation in Furniss is doubly amusing as it occurs before an audience of workhouse crones, from whose perspective the reader views Bumble's hasty retreat as Mrs. Bumble douses him. Like Cruikshank's illustration, this Furniss lithograph depicts Mrs. Bumble's utilising the women in the workhouse to get the better of her new husband, who cowers before her, and then retreats expeditiously in this marital farce, stage left.

It is informative to consider the adjustments that Furniss has made to Cruikshank's Mr. Bumble degraded in the eyes of the Paupers. Furniss's choosing to revise the Cruikshank orginal was indeed daring as the 1838 would seem to be a triumph of the earlier artist's visual satire. The five cartoon-like washerwomen of the original become three disembodied heads in the diaphonous backdrop and two emaciated but fully shown spectators whose perception of their social "superiors" is, implies Furniss, normative.

In the 1838 steel engraving, Cruikshank makes husband and wife in the centre the largest figures and the twin focal points of the comic scene: already Mrs. Bumble is forcing her astonished husband towards the right margin (in which Furniss locates a door), much to amusement of the gaunt laundresses (left). This is no longer the demure, tea-drinking matron of Cruikshank's earlier Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney taking tea, in which she was very much to the left of centre in a private setting while her suitor dominated the composition, leaning in rather than, as in this later illustration, turning away; here, in a scene played out before her institutional charges, the matron seems to have grown in size and stature, having exchanged her diminutive teacup for a large saucepan. In her workplace identity, she is no longer a prim Victorian widow; rather, in her office she fills the scene, becoming a vessel of war (with billowing sail) or figurehead who commands rather than demures — a veritable virago. Whereas the tea-drinking scene occurs in the confines of a domestic space defined by the furnishing and bric-a-brac typical of a nineteenth-century parlour, Cruikshank and Furniss present no background details to establish the size or nature of the laundry room in the workhouse, so that the figures of the Bumbles stand out against the vapour and suds which obscure the upper register of both the 1838 and 1910 illustrations.

The expectations of the formerly haughty Bumble regarding the obedience of his wife, the former Mrs. Corney, two months after their marriage are dashed by her face-saving ploy in front of her female charges at the workhouse, for such refuges for the destitute, infirm, and unemployed practiced gender segregation, even to the point of dividing families. (Although the underlying intention of workhouse guardians was simply to prevent procreation among the poor, the vast majority of inmates were elderly and infirm.) The incident is not a mere comeuppance for the beadle in that it marks a shift in his erstwhile alliance with the matron of the workhouse. Retreating from his wife's sphere of influence, which the presence of numerous laundry women defines as an Amazonian space, to the masculine sanctuary of a nearby public house, Bumble is approached by a well-dressed, enigmatic stranger who is looking for information about Oliver's mother. Thus, the contest of wills between the formerly self-confident husband and formerly unassertive wife sets up the plot-oriented scene involving Monks and the secret of Oliver's birth in Harry Furniss's sequence.

Furniss in The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910) revisits the comedic scene so deftly handled by Cruikshank, undoubtedly enjoying the opportunity to show the exploiters falling out. In the Furniss treatment, the retreating Bumble is derived from Cruikshank's highly theatrical composition. Whereas James Mahoneyin the Household Edition has deliberately selected for illustration scenes involving Mrs. Corney and Mr. Bumble that relate them only to the plot and do not indulge in his predecessor's penchant for visual satire and character comedy, Harry Furniss again pays homage to the original scene selected by Dickens and Cruikshank for the serial. Indeed, Furniss has borrowed the costumes, juxtapositions, properties, poses, and expressions of Cruikshank's couple, but in a Baroque manner has altered the perspective so that the pauper women, the delighted audience of the momentary domestic comedy, are no longer stage right, but in fact are downstage, so that Furniss's viewer surveys the routing of former beadle (no longer habited as such) from behind the angular, ill-fed women and their washtubs. As in the earlier illustration, clouds of steam (suggestive of Mrs. Bumble's frothing ill-temper) envelop the upper register, but in Furniss's treatment Bumble is only partially visible as he is already abandoning the field of battle to the fairer sex, even as his wife pours the suds on him. He begins by criticizing female unruliness, buts ends engulfed in soap suds, symbol of domestic labour. Thus, Furniss's energetic realisation completes the action begun in Cruikshank's. Furniss expands the role of the female audience, foregrounding the normative observers and relegating the battling principals to the rear of the arena of conflict, the wash-house.

Bibliography

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1838; rpt. with revisions 1846.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

_____.The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. I (1820-1839).

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. I, Book 2, Chapter 3.

Herr, Joelle. "Oliver Twist." Charles Dickens: The Complete Novels in One Sitting. Philadelphia and London: Running Press, 2012, 34-46.

Jordan, John O. "The Purloined Hankerchief." Chapter 3, "A Critical Selection." Readings on Charles Dickens "Oliver Twist.". Greenhaven Press Literary Companion to British Literature. Originally in Dickens Studies Annual, 1989. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven, 2001, 167-83.

Kyd (Clayton J. Clarke). Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Pailthorpe, Frderick W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Vann, J. Don. "Oliver Twist." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985, 62-63.

Created 25 February 2015

Last modified 15 February 2020