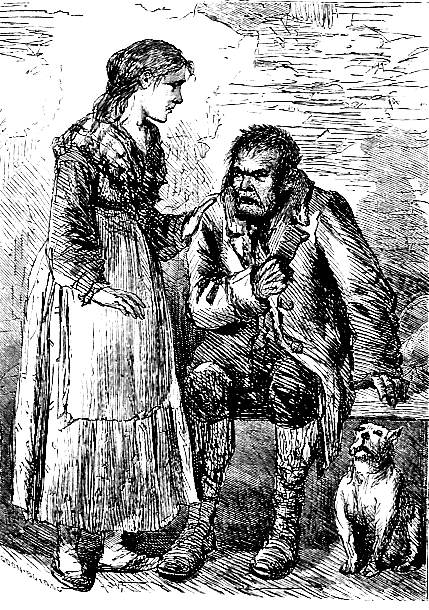

"Rose and Nancy" by Harry Furniss — twenty-fifth illustration for Dickens's "Adventures of Oliver Twist" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

"Your having interfered in this dear boy's behalf before," said Rose; "your coming here, at so great a risk, to tell me what you have heard; your manner, which convinces me of the truth of what you say; your evident contrition, and sense of shame; all lead me to believe that you might yet be reclaimed. Oh!" said the earnest girl, folding her hands as the tears coursed down her face, "do not turn a deaf ear to the entreaties of one of your own sex; the first — the first, I do believe, who ever appealed to you in the voice of pity and compassion. Do hear my words, and let me save you yet, for better things."

"Lady," cried the girl, sinking on her knees, "dear, sweet, angel lady, you are the first that ever blessed me with such words as these, and if I had heard them years ago, they might have turned me from a life of sin and sorrow; but it is too late, it is too late!"

"It is never too late," said Rose, "for penitence and atonement."

"It is," cried the girl, writhing in agony of her mind; "I cannot leave him now! I could not be his death." [Chapter 40, "A Strange Interview, which is a Sequel to the Last Chapter," 308]

Commentary: Dickens’s Theory of Melodrama and Nancy’s Moral Growth

Harry Furniss follows up the change in Nancy's character by depicting the emotional interview between the virtuous, upper-middle-class Rose and the girl of the streets. Treated with compassion, Nancy breaks down as she reports the Monks-Fagin plot against Oliver. The way Furniss constructs the scene in a way consistent with Dickens's own ideas about melodrama. Earlier in the novel, Dickens stipulates that an effective melodrama requires an alternation of dark, serious and lighter, comic scenes. Conversely, Cruikshank in the periodical sequence follows up the comic scene of Nancy's "hysterics" with yet another comic interlude, The Jew & Morris Both begin to understand each other, in which the devious Noah, having absconded with the contents of the Sowerberrys' shop till — and their maid, Charlotte — follows the Great North Road to London and falls in with Fagin. The master criminal just happens to be looking for a new associate utterly unknown to Nancy so that he can have her watched and followed. Furniss, on the other hand, follows up the comic scene of Nancy, Bill Sikes, and the gang with a highly emotional scene, as is consistent with Dickens's theory of "streaky bacon" scene construction:

It is the custom on the stage, in all good murderous melodramas, to present the tragic and the comic scenes, in as regular alternation, as the layers of red and white in a side of streaky well-cured bacon. The hero sinks upon his straw bed, weighed down by fetters and misfortunes; in the next scene, his faithful but unconscious squire regales the audience with a comic song. [Ch. 17, p. 120 in the 1910 edition]

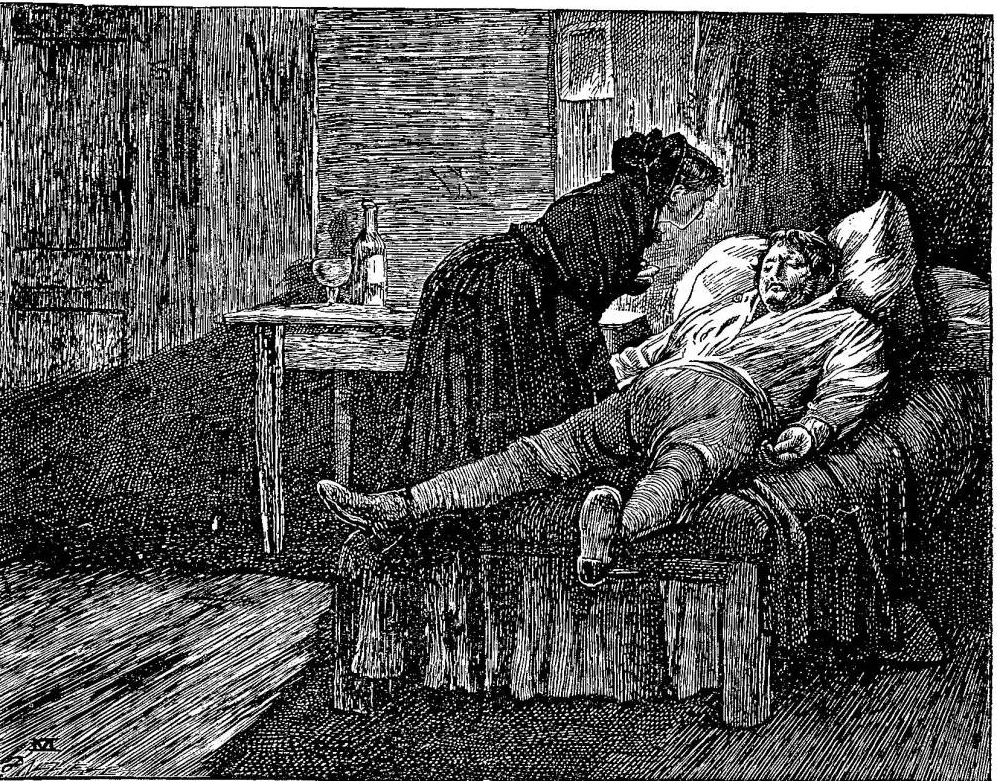

In Furniss's sequence, the serious scene follows the comic interlude; however, both comic and serious illustrations signal the change in Nancy's character that is necessary to advance the plot of her informing on Fagin and Monks, and of her subsequently being murdered by Sikes (at Fagin's instigation) as a police informant, which in fact, as the Furniss scene underscores, she is not. Other illustrators have shown Nancy's moral growth in less emotional scenes. For example, James Mahoney created , Then, stooping softly over the bed, she kissed the robber's lips (see below).Mahoney's treatment of the scene does not make clear, however, that Nancy has, in fact, drugged Sikes to ensure that she can keep her appointment with Rose Maylie at her West End hotel without fear of being followed or interrogated afterwards — an anxious journey that F. W. Pailthorpe describes in his 1886 hand-tinted engraving "Has it long gone the half-hour?" (see below), which provides a much more sympathetic Nancy, fearful that she is being trailed by the gang. However, the Mahoney illustration does underscore the anomaly in Nancy's character, expressed in the text accompanying Furniss's, that Nancy believes she can remain true to Sikes even as she seeks to defend Oliver.

In Furniss's illustration, Rose seems shocked at Nancy's breaking down as she grapples with a powerful ethical conflict, namely how to remain true to her brute of a husband while defending Oliver and ensuring the downfall of "Monks" by informing Mr. Brownlow and Rose Maylie of the plot to drag the boy into the criminal underworld. Thus ennobled by her intent, Nancy speaks the emotionally heightened, grammatically correct language of melodrama rather than the dialect of the streets. Furniss lends her a convincing, entreating, contrite, and even desperate posture as shehides her tearful face from a respectably dressed woman of about her own age. Furniss has lightly sketched in the background to make the contrasting figures stand out: Rose, of the affluent suburbs, stands, but must support herself on a chair, as she looks down in pity and sympathy upon this wayward but reformed young man of the criminal classes. The hotel room bespeaks tasteful and leisured living, with padded furniture, draperies, a painting, bric-a-brac on the mantle, and a fireplace screen. The inward, pained look on Rose's face may well reflect her own inner turmoil as the mystery surrounding her birth has led her to reject her adopted brother, Harry, as a suitor since such a questionablealliance would likely damage his political career. The gulf between herself at seventeen and Nancy (apparently of much the same age) may not be so great, after all, she may be considering, despite their most obvious difference, that of dress, the signifier of their respective classes.

Nancy in Illustrations from the Original 1837-38 Serial Publication and Later Editions

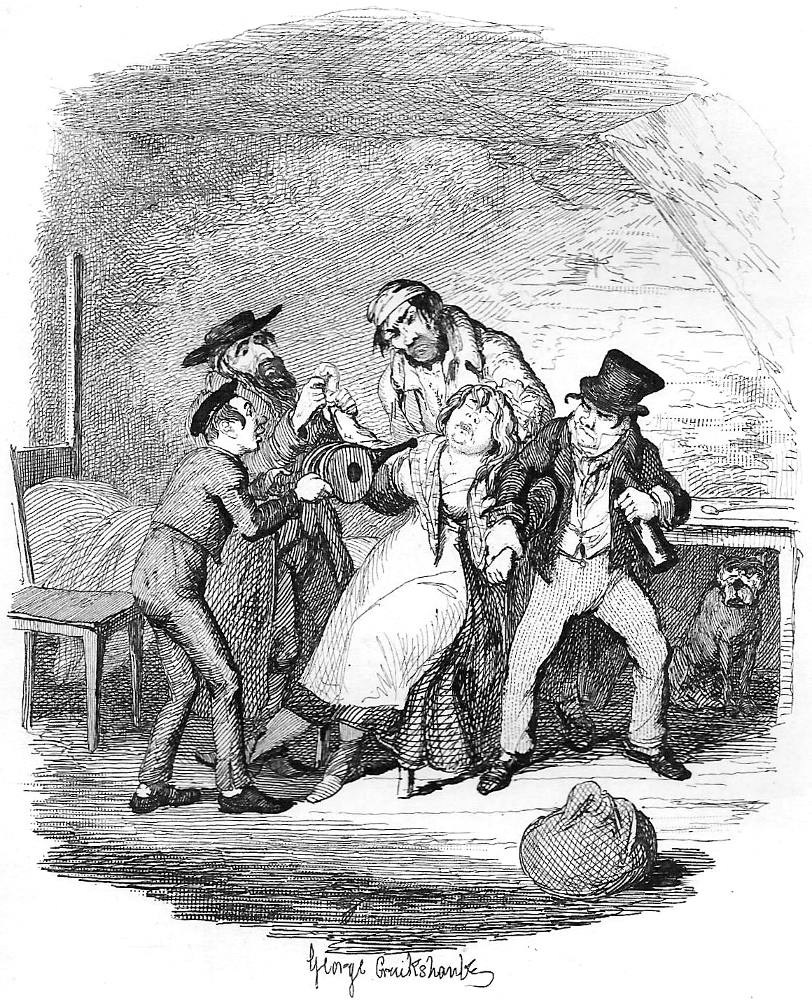

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's Bill Sikes and Nancy (1867). Centre: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's Sikes, Nancy, and Oliver Twist (1888). Right: George Cruikshank's illustration Mr. Fagin and his pupils recovering Nancy (Part 18, October 1838).

Left: F. W. Pailthorpe's "Has it long gone the half-hour?" (1886). Centre: Charles Pears' pencil study, Nancy. Right: Kyd's original watercolour study of a rough-and-ready woman of the streets rather than a reformed prostitute, Nancy (c. 1900). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Above: Mahoney's 1871 engraving of Nancy ministering to Sikes, whom she has just drugged so that she keep a rendez-vous with Rose: Then, stooping softly over the bed, she kissed the robber's lips.

Bibliography

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1838; rpt. with revisions 1846.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

_____.The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. I (1820-1839).

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. I, Book 2, Chapter 3.

Jordan, John O. "The Purloined Hankerchief." Chapter 3, "A Critical Selection." Readings on Charles Dickens "Oliver Twist.". Greenhaven Press Literary Companion to British Literature. Originally in Dickens Studies Annual, 1989. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven, 2001, 167-83.

Kyd (Clayton J. Clarke). Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

McMaster, Juliet. "The Evil Triumvirate." Chapter 3, "A Critical Selection." Readings on Charles Dickens "Oliver Twist". Greenhaven Press Literary Companion to British Literature. Originally in Dickens Studies Annual, 1989. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven, 2001, 184-96.

Pailthorpe, Frderick W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Vann, J. Don. "Oliver Twist." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985, 62-63.

Created 5 March 2015

Last modified 18 February 2020