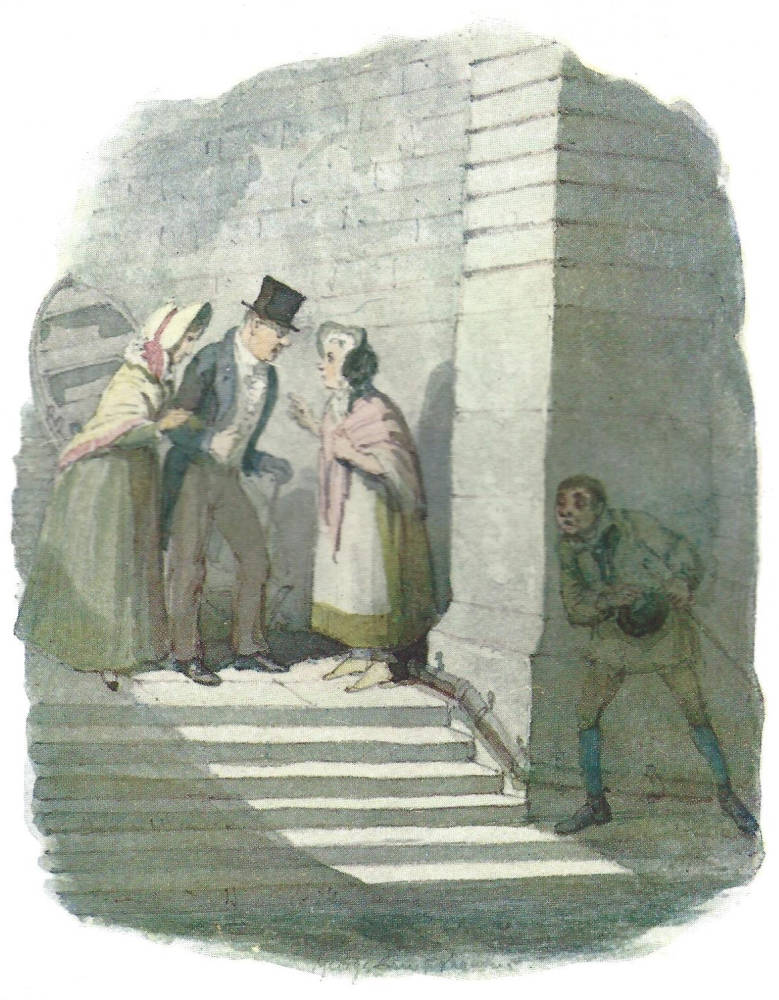

"The Meeting under London Bridge" by Harry Furniss — twenty-eighth illustration for Dickens's "Adventures of Oliver Twist" (1910) (original) (raw)

"You put yourself beyond its pale," said the gentleman. "The past has been a dreary waste with you, of youthful energies mis-spent, and such priceless treasures lavished, as the Creator bestows but once and never grants again, but, for the future, you may hope. I do not say that it is in our power to offer you peace of heart and mind, for that must come as you seek it; but a quiet asylum, either in England, or, if you fear to remain here, in some foreign country, it is not only within the compass of our ability but our most anxious wish to secure you. Before the dawn of morning, before this river wakes to the first glimpse of day-light, you shall be placed as entirely beyond the reach of your former associates, and leave as utter an absence of all trace behind you, as if you were to disappear from the earth this moment. Come! I would not have you go back to exchange one word with any old companion, or take one look at any old haunt, or breathe the very air which is pestilence and death to you. Quit them all, while there is time and opportunity!"

"She will be persuaded now," cried the young lady. "She hesitates, I am sure."

"I fear not, my dear," said the gentleman.

"No sir, I do not," replied the girl, after a short struggle. "I am chained to my old life. I loathe and hate it now, but I cannot leave it. I must have gone too far to turn back, — and yet I don’t know, for if you had spoken to me so, some time ago, I should have laughed it off. But," she said, looking hastily round, "this fear comes over me again. I must go home."

"Home!" repeated the young lady, with great stress upon the word.

"Home, lady," rejoined the girl. "To such a home as I have raised for myself with the work of my whole life. Let us part. I shall be watched or seen. Go! Go! If I have done you any service all I ask is, that you leave me, and let me go my way alone."

"It is useless," said the gentleman, with a sigh. "We compromise her safety, perhaps, by staying here. We may have detained her longer than she expected already."

"Yes, yes," urged the girl. "You have."

"What," cried the young lady, "can be the end of this poor creature’s life!"

"What!" repeated the girl. "Look before you, lady. Look at that dark water. How many times do you read of such as I who spring into the tide, and leave no living thing, to care for, or bewail them. It may be years hence, or it may be only months, but I shall come to that at last."

"Do not speak thus, pray," returned the young lady, sobbing. [Chapter 46, "The Appointment Kept," 357-58; the words of the original caption have been emphasized]

The Charles Dickens Library Edition’s Long Caption

"Look before you, lady. Look at that dark water. How many times do you read of such as I who spring into the tide, and leave no living thing, to care for, or bewail them. [358]

The Clandestine Meeting in Illustrations and Dramatic Adaptations

Dickens's original illustrator, George Cruikshank in the December 1838 number of Bentley's Miscellany provided a dramatic scene in which Noah Claypole, Fagin's agent, overhears some of the clandestine conversation between Nancy, Mr. Brownlow, and Rose Maylie about Monks' plotting against Oliver. Furniss's impressionistic revision of Cruikshank’s engraving places Noah behind rather than in front of the figures under New London Bridge. To heighten the suspense of the secret rendezvous, the 1868 stage adaptation at the Lyceum substituted Bill Sikes and Fagin for Noah in this critical scene, which served as the basis for the theatre's promotional poster, which alludes to Franklin Dyall as Sikes, and Mary Merrall as Nancy, implying that Nancy's murder rather than the death of Sikes and the arrest of Fagin is the adaptation's climax. The new, wider bridge designed by John Rennie to accommodate increased traffic was itself torn down in 1968. (New London Bridge, carefully reproduced in the stage set as the poster, is now thousands of miles from England as "Nancy's Steps" from the Surrey side, like the rest of the bridge since 1973 been in Lake Havasu City, Arizona, transported and reassembled stone by stone.)

In the celebrated 1838 illustration, Cruikshank depicts the moment when, having tracked Nancy across the East End, Noah overhears Sikes's mistress disclosing the plans laid by Fagin and Monks to ensure that Oliver will never come into his inheritance. In Furniss's sequence this serious scene follows the comic interlude in which, again with Noah as witness to the proceedings, the Artful Dodger is arraigned for petty larceny in the Magistrate's court — The Artful Dodger before the Magistrates (Chapter 43). In the third volume of the Household Edition, James Mahoney in 1871 had taken a different approach by showing a disguised Noah shadowing Nancy across London Bridge rather than actually overhearing the conversation on the stairs.

Above: Mahoney's 1871 engraving of Noah's trailing Nancy to New London Bridge, fitfully lit by gas lamps, "When she was about the same distance in advance as she had been before, he slipped quietly down.".

Thus, Mahoney builds suspense throughWhen she was about the same distance in advance as she had been before, he slipped quietly down (see below), focussing on the foregrounded spy in disguise, and positioning Nancy in the distance on the bridge deck (rear), and thereby avoiding the scene already realized by Cruikshank.

In Furniss's illustration, the caption points to a later moment in the interview when, fearing detection, Nancy determines to return to the brutal burglar who frequently abuses her. Again, Rose is shocked at Nancy's predicament, but Mr. Brownlow tries to make the privileged young woman from the suburbs understand that Nancy as a girl of streets has few options. Thus, the caption in Furniss's illustration points towards Nancy's terrible fate at the hands of Bill Sikes, and even foreshadows the destruction of the entire gang. Here, a curious Noah peers around a pillar on the river side (rear) to observe the meeting, the illustrator signalling Nancy's agitation by depicting her dress almost in motion, while Rose's dress is perfectly still. Goggle-eyed, Noah carries the carter's whip that Mahoney gave him in the 1871 illustration. The arches of the bridge now dominate the scene, and one has little sense of the landing-stairs as Furniss has moved in, as it were, for a closeup. Rose remonstrates with Nancy, perhaps naively hoping that she can persuade the girl not to return to Sikes; Nancy, clearly alarmed, gathers her shawl about her and turns, as if making for the stairs.

Although Dickens is highly specific in his description of the setting for the clandestine meeting — "The steps to which the girl had pointed, were those which, on the Surrey bank, and on the same side of the bridge as Saint Saviour's Church, form a landing-stairs from the river — and even alludes to an architectural element in the new bridge's design as Noah, eavesdropping, has "his back to the pilaster," there is nothing in particular in Cruikshank's depiction that would suggest New London Bridge specifically. However, subtly includes the unicorn boss (foreground). This "new" structure, built in 1831 and inaugurated with much fanfare on 1 August of that year, replaced a 600-year-old medieval structure (dating from 1209) that was literally "falling down." Since the new bridge would have been familiar to Dickens's original serial readers, this setting must have brought the story into the lives of the book's readers, making the subsequent events (the murder of Nancy, the pursuit of Sikes, and the execution of Fagin) insistently real. Thus, this is one of those magic points in the narrative when the fabular city of ballad, the modern Babylon and Dick Whittington's metropolis of opportunity, becomes the actual City of London in the 1830s, and the story a documentary of the criminal underworld at the reader's doorstep: As Michael Slater points out, “The London in which the action takes place is both the actual city of the 1830s — with all the respectable areas left out — and a dark and sinister labyrinth perpetually shrouded in night. The way Dickens describes Oliver's nocturnal entry into the city, escorted by the Artful Dodger, exemplifies this perfectly” (56):

They crossed from the Angel into St. John's Road; struck down the small street which terminates at Sadler's Wells Theatre; through Exmouth Street and Coppice Row; down the little court by the side of the workhouse; across the classic ground w.ich once bore the name of Hockley-in-the-Hole; thence into Little Saffron Hill; and so into Saffron Hill the Great: along which the Dodger scudded at a rapid pace, directing Oliver to follow close at his heels. [Chapter 8]

This sentence creates the feeling “of the hapless Oliver's being drawn deeper and deeper into a dangerous maze” (56). Nonetheless, the specificity of Dickens's description of "The Meeting" in Chapter 46 reminds the thoughtful reader that this is not the historical city of Sir Walter Scott's Jeanie Deans in The Heart of Midlothian (1818) or of Henry Fielding's Tom Jones (1749), the destination at the end of the Great North Road in pre-nineteenth-century picaresque fiction, but the real London of the present, a city whose vice and crime and grinding poverty the thoughtful reader cannot dismiss as the fictional construct of an imaginative, moralising journalist and social activist.

Illustrations from the original 1837-38 serial publication and later editions

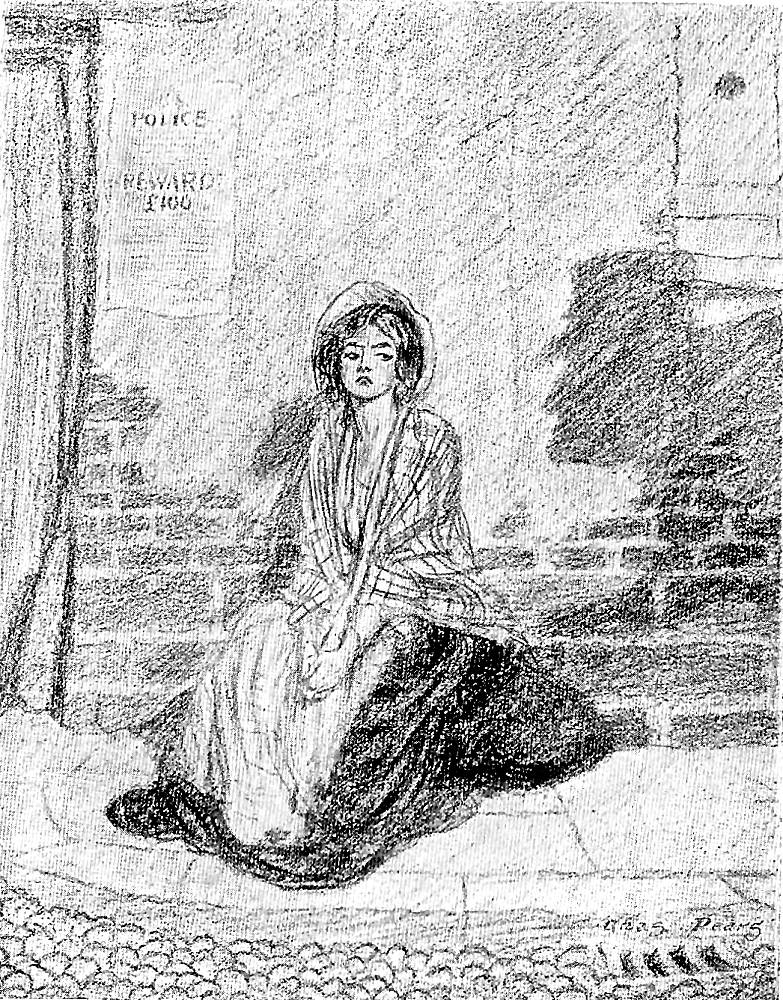

Left: Cruikshank's illustration The Meeting(Part 20, December 1838). Centre: F. W. Pailthorpe's "Has it long gone the half-hour?" (1886). Right: Charles Pears' pencil study, Nancy.

Bibliography

Bolton, H. Philip. "Oliver Twist." Dickens Dramatized. Boston and London: G. K. Hall, 1987, 104-53.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1838; rpt. with revisions 1846.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

_____.The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. I (1820-1839).

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. I, Book 2, Chapter 3.

Kyd (Clayton J. Clarke). Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Pailthorpe, Frederic W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Slater, Michael. "Fictional Modes in Oliver Twist. Rpt. in Readings on Charles Dickens "Oliver Twist". Literary Companion to British Literature. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven, 2001. Pp. 53-61. Originally published in the Dickensian, May, 1974.

Vann, J. Don. "Oliver Twist." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985, 62-63.

Created 5 March 2015

Last modified 1 March 2020