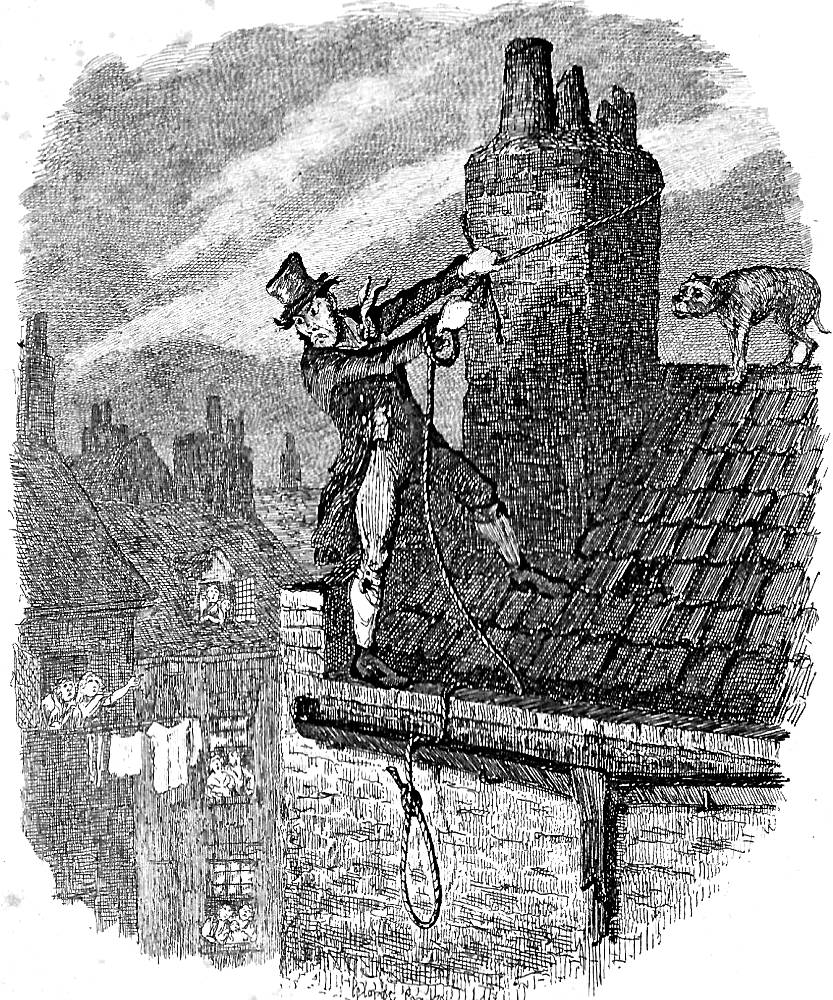

"The Death of Sikes" by Harry Furniss — thirty-first illustration for Dickens's "Adventures of Oliver Twist" (1910) (original) (raw)

Context of the Illustration

"The eyes again!" he cried in an unearthly screech.

Staggering as if struck by lightning, he lost his balance and tumbled over the parapet. The noose was on his neck. It ran up with his weight, tight as a bow-string, and swift as the arrow it speeds. He fell for five-and-thirty feet. There was a sudden jerk, a terrific convulsion of the limbs; and there he hung, with the open knife clenched in his stiffening hand.

The old chimney quivered with the shock, but stood it bravely. The murderer swung lifeless against the wall; and the boy, thrusting aside the dangling body which obscured his view, called to the people to come and take him out, for God's sake.

A dog, which had lain concealed till now, ran backwards and forwards on the parapet with a dismal howl, and collecting himself for a spring, jumped for the dead man's shoulders. Missing his aim, he fell into the ditch, turning completely over as he went; and striking his head against a stone, dashed out his brains. [Chapter 50, "The Pursuit and Escape," 393-94.]

Commentary: The Death of Sikes from Cruikshank to Furniss and Beyond

Dickens's original illustrator, George Cruikshank in Bentley's Miscellany provided a sensational rooftop scene to complement Sikes's accidentally hanging himself in the text in The Last Chance (Part 22, February 1839). The present lithograph is Furniss's response to that original engraving, and also to the James Mahoney wood-engraving for Chapter 50 in the third volume of theHousehold Edition,And creeping over the tiles, looked over the low parapet. In the present lithograph, a cartoon-like Bull's-Eye looks curiously down the length of taught rope, presumably at his master in his death throes. Cruikshank depicts the very moment before Sikes falls to his death, a victim of Nemesis or Poetic Justice, followed shortly by his faithful dog, the enforcer of his master's will. And so the tormentors of Oliver and Nancy's murderer are punished by Fate — or coincidence. The readers of theHousehold Edition find an illustration that anticipates both Sikes's fall and Bull's-Eye's disclosure before the fatal event.

Thinking to avoid detection and capture, Sikes hopes to throw the authorities off the scent by returning to the vicinity of the crime scene, hoping to lay low for a few days in fellow-burglar Toby Crackit's iron-shuttered safe-house on Jacob's Island (only truly an island in those days when the tide was in) before slipping across the Channel to start a new life in France. In Dickens's England, Tony Lynch notes that the modern tourist, searching the London grid, will be hard pressed to find revenants of Jacob's Island, a byword for vice, crime, and deplorable sanitation in Dickens's time. As Tony Lynch has explained, “Jacob's Island once lay a mile to the east of London Bridge on the south side of the River Thames. The area has long since been 'improved away' and now forms that part of Bermondsley bounded by Mill Street, Jacob Street and George Row. In the 1830s the island — so named because it was cut off at high tide by a stretch of water known as Folly Ditch — was a maze of narrow, muddy alleyways between grim tenement buildings” (122). The squalid slum retained something of its original character even at the turn of the century with its wooden, two-storey houses assembled from material left over from wharf construction and ship-building. In the 1830s it rivalled Field Lane as a centre of vice and crime — and is therefore the logical locale for Toby Crackit's safe-house and Sikes's demise. Mahoney's illustration features the roof and parapet, but not that one of the many chimneys of the houses at Jacob's Island that proves instrumental in Sikes's accidental hanging. Whether he realised it or not, in focussing on the figure of Sikes Mahoney was actually addressing a series of objections that Dickens had posed to Cruikshank regarding making the escape scene the subject of an illustration for the forthcoming Bentley triple-decker: "I find on writing it, that the scene of Sikes's escape will not do for illustration. It is so very complicated, with such a multitude of figures, such violent action, and torch-light to boot, that a small plate could not take in the slightest idea of it" ("?6 October 1838," Letters, I, 440).

Whereas Furniss in his 1910 lithographic series offers three illustrations depicting the sensational events in the final days of the Hogarthian blackguard — the dark plate The Death of Nancy, the humorous taproom scene at The Eight Bells, The Flight of Bill Sikes, and this peculiar rendition of Sikes's hanging in which Sikes himself is not in the frame at all, The Death of Sikes, the 1871 volume by the Household Edition illustrator James Mahoney depicts Sikes's studying his pursuers from the roof top of the Toby Crackit's hideout on Jacob's Island rookery in And creeping over the tiles, looked over the low parapet (see below). In contrast, Dickens's chief American illustrator, Sol Eytinge, Junior, offers a portrait of the dissolute burglar and his bedraggled doxy in Chapter 39, but has no illustrations inserted into the chapters in which Sikes murders Nancy, flees, and in a sensational scene worthy of dramatist Dion Boucicault falls to his death in a final bid to cheat the law. F. W. Pailthorpe (1886) effectively dramatizes how the gang respond to Sikes's crime with the recently arrived Charley Bates's denunciation of him at the safe-house, "Don't come near me, You monster!" (see below). Furniss's approach is more oblique, and requires more imaginative engagement of the reader.

The dark blotch on the wall of the safe-house may represent the shadow cast by Sikes's lifeless body. That something upon which readers' imaginations must work lies outside the lower left frame is signalled by Bull's-Eye's gaze and the downward pointing gestures of the denizens of Jacob's Island at their windows, a detail borrowed from the Cruikshank original. Opposite the proleptic illustration, ten pages before the passage realised, Furniss's readers would have seen the description of the people watching the drama unfolding on the rooftop opposite:

In such a neighborhood, beyond Dockhead in the Borough of Southwark, stands Jacob’s Island, surrounded by a muddy ditch, six or eight feet deep and fifteen or twenty wide when the tide is in, once called Mill Pond, but known in the days of this story as Folly Ditch. It is a creek or inlet from the Thames, and can always be filled at high water by opening the sluices at the Lead Mills from which it took its old name. At such times, a stranger, looking from one of the wooden bridges thrown across it at Mill Lane, will see the inhabitants of the houses on either side lowering from their back doors and windows, buckets, pails, domestic utensils of all kinds, in which to haul the water up; and when his eye is turned from these operations to the houses themselves, his utmost astonishment will be excited by the scene before him. Crazy wooden galleries common to the backs of half a dozen houses, with holes from which to look upon the slime beneath; windows, broken and patched, with poles thrust out, on which to dry the linen that is never there; rooms so small, so filthy, so confined, that the air would seem too tainted even for the dirt and squalor which they shelter; wooden chambers thrusting themselves out above the mud, and threatening to fall into it — as some have done; dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations; every repulsive lineament of poverty, every loathsome indication of filth, rot, and garbage; all these ornament the banks of Folly Ditch. [384]

In Furniss's illustration which calls for imaginative recreation of the moment of Sikes's death, the artist has provided a wilderness of blackened chimneys, blotched and cracking walls, and spectators at their windows, sashes thrown up. Thus, the picture of the moments after the murder relies for its complete decoding on the material on the facing page which establishes the particulars of the unsavoury setting, Sikes's last resort, hardly the haunt of a dashing highwayman of the John Gay variety; in his ending as in his life, Bill Sikes has proven to be no Captain Macheath from the 1726 ballad opera. There is no romance on Sikes's gloomy road.

Illustrations from the original 1837-38 serial publication and later editions

Left: Cruikshank's The Last Chance (1839). Centre: from Cruikshank's 1846 serial wrapper,Sikes's death, detail from the lower-right corner. Right: F. W. Pailthorpe's 1886 illustration of Charley Bates's denunciation of Sikes, "Don't come near me, You monster!".

Above: Mahoney's 1871 engraving of the moments immediately before Sikes' death, And creeping over the tiles, looked over the low parapet.

Bibliography

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1838; rpt. with revisions 1846.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

_____.The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. I (1820-1839).

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. I, Book 2, Chapter 3.

Kyd. Characters of Charles Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Lynch, Tony. "Jacob's Island, London." Dickens's England: An A-Z Tour of the Real and Imagined Locations. London: Batsford, 2012. Pp. 122.

Pailthorpe, Frderick W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Vann, J. Don. "Oliver Twist." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985, 62-63.

Created 13 March 2015

Last modified 1 March 2020