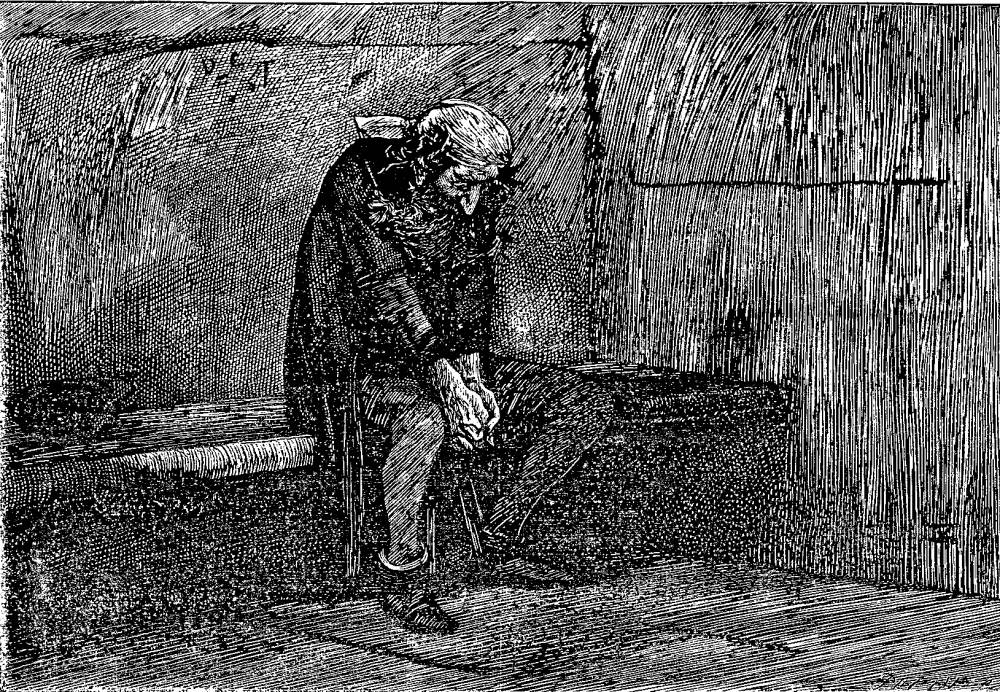

"Fagin in the Condemned Cell" by Harry Furniss — thirty-third illustration for Dickens's "The Adventures of Oliver Twist" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

He sat down on a stone bench opposite the door, which served for seat and bedstead; and casting his blood-shot eyes upon the ground, tried to collect his thoughts. After awhile, he began to remember a few disjointed fragments of what the judge had said: though it had seemed to him, at the time, that he could not hear a word. These gradually fell into their proper places, and by degrees suggested more: so that in a little time he had the whole, almost as it was delivered. To be hanged by the neck, till he was dead — that was the end. To be hanged by the neck till he was dead.

As it came on very dark, he began to think of all the men he had known who had died upon the scaffold; some of them through his means. They rose up, in such quick succession, that he could hardly count them. [Chapter 52, "Fagin's Last Night Alive," 409]

The Charles Dickens Library Edition’s Long Caption

He sat down on a stone bench opposite the door, which served for seat and bedstead; and casting his blood-shot eyes upon the ground, tried to collect his thoughts. [409]

Illustrations of Fagin, the most interesting character in Oliver Twist

Dickens's description of "Fagin's Last Night Alive" makes him seem all too human as he contemplates not only his own fate — "to be hanged by the neck until dead" the next morning in a public execution — but also the fates of previous occupants of his cell. In contrast, Furniss’s illustration, which depicts Fagin with glowing eyes, suggests that he is a caged beast or man possessed. Furniss had seen the twenty-eight illustrations by James Mahoney for the novel in the The Household Edition (1871) as well as the work of Dickens's original illustrator, George Cruikshank, but he rarely chose to follow their work except in Characters in the Story whose impressionistic sketches of = forty-five figures serve as a tribute to Cruikshank's illustrations. Although Fagin in the Condemned Cell (see below) does not appear on this summary title-page, Furniss has placed him prominently with his pickpocketing crew in the upper left-hand register of the ornamental border, and he also has him appear in a further six illustrations. In other words, Fagin appears in more than twenty percent of the narrative-pictorial sequence, or roughly in the same proportions (six out of the twenty-four engravings) in the original Cruikshank drawings made expressly at Dickens's behest.

In his introduction to the Waverley edition of the novel in 1912, A. C. Benson observes that the novel's good people, the Maylies and Mr. Brownlow in particular, are "intolerably uninteresting," and that even the heroic Oliver for most of the story "is a mere guileless and stainless phantom" (xi).Even the brutal Sikes is more interesting, in his sheer will to survive, no matter what the costs to others. But, best of all is Fagin, a criminal mastermind who nevertheless seems to care about the boys in his charge, although he would never admit to the weakness of caring for anybody but himself. Like Nancy, Fagin has depth, so that it is not his badness that renders him attractive, but his relative complexity.

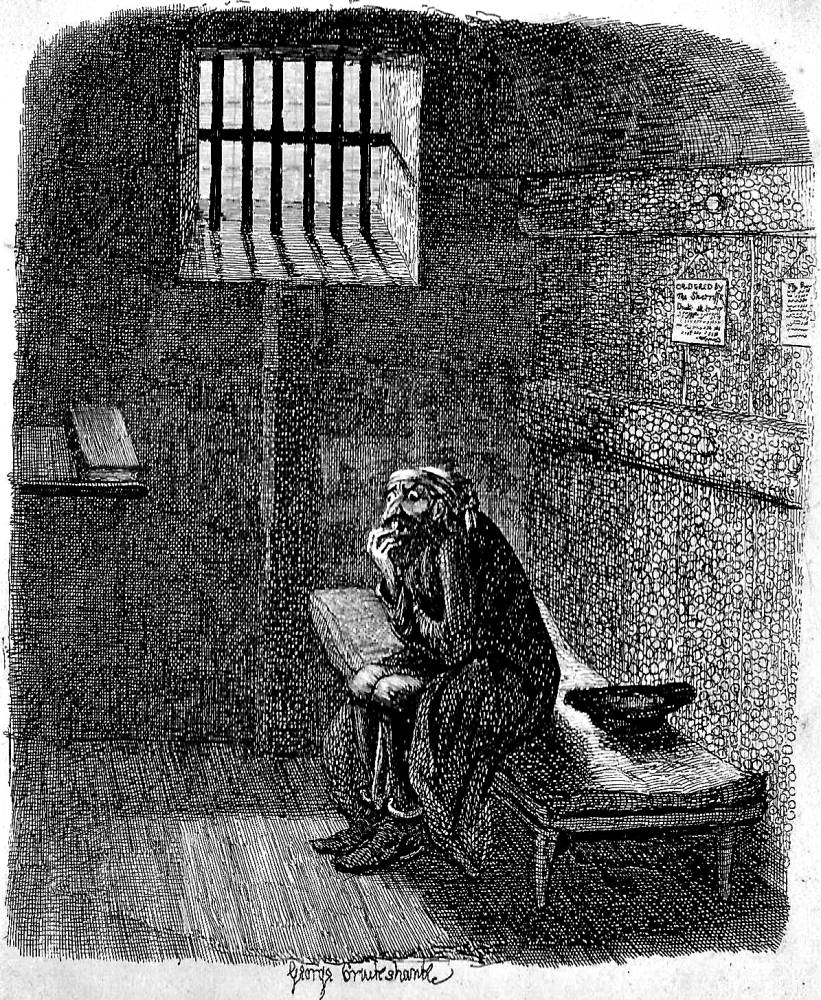

Our interest in Fagin rises to a crescendo in Chapter 52. Although other illustrators have shown the condemned Fagin awaitingexecution at Newgate, Cruikshank's treatment of both the prisoner and the physicalsetting remains the locus classicus because of the plate's conveying witheffective economy the starkness of the chamber and the psychological unravelling of theinmate. Aware that one of the sordid, lower-class villains — Sikes, or Fagin— would probably finish the novel in Newgate Prison, Cruikshank did multiple studies of bothcriminals in the condemned cell. Eventually, of course, once he had read the concluding chapters in manuscript, he learned that the solitary prisoner facing execution would be Fagin; however, he struggled to find exactly the right poseand facial expression to convey the internal conflict of the condemned man who, in Dickens's text, experiences a greatrange of reactions to his own impending death.

Cruikshank's treatment of the subject of the condemned criminal awaiting execution has, of course, become iconic, influencing numerous later artists' depictions of such situations, and perhaps even influencing illustrators of Great Expectations in the scene in which Magwitch dies in prison after killing Compeyson on the Thames, although, as illustrator John McLenan notes, Magwitch does not die alone and unfriended in The placid look at the white ceiling came back, and passed away, and his head dropped quietly on his breast in Harper's Weekly 5 (27 July 1861): 447. While the 1861 shows Magwitch at peace, facing death with his "dear boy" beside him, the key word in the passage realized in the Mahoney plate is "— alone" (200).

Mahoney's study of a felon awaiting execution, Fagin in the Condemned Cell (1871).

Although the 1870s Household Editionillustrator James Mahoney depicts Fagin in his last hours, his treatment of his subject clearly subsumes the slightly more caricaturistic treatment of Cruikshank. Having depicted Fagin with his open cash-box at the very beginning of his sequence of character studies, Sol Eytinge had no opportunity to revisit the character, and, perhaps as a consequence of Cruikshank's memorable plate, no inclination to attempt to outdo Dickens's original illustrator. Mahoney, on the other hand, obviously felt that he could recreate the highly dramatic moment in a more realistic manner in the Newgate cell as He sat down on a stone bench opposite the door(see below) pays homage to Cruikshank's original conception, but eliminates the theatrical properties and gestures to focus on Fagin's tortured inner state. Like Mahoney, Furniss includes neither the bars (seen only in a teeth-like shadow cast onto the floor, lower left) or bible and table from the Cruikshank plate, and dispenses with the two embedded, hand-written notes above the prisoner. The only ornamentation in Furniss's lithograph is the figure of the prisoner himself, in the whirling motion of his clothing contrasting his complete stillness. There is neither table, nor Bible, nor window: the focus is entirely on the manacled criminal contemplating his own imminent death — and glaring out of the frame, at the reader.

Whereas Cruikshank provides visual continuity by dressing Fagin in much the same clothing throughout, and consistently emphasizes his bulging eyes, here he is neither in motion or in company; he becomes in his isolation a pitiable figure worthy of some compassion. After all, although a career criminal and receiver of stolen goods, Fagin is hardly guilty of violent crimes so that, unlike Sikes, the death of Fagin seems disproportionate to his actions. In fact, only his inciting Sikes to murder Nancy can excuse Fain's sentence, which otherwise would be transportation, the fate that has attended the other members of his pickpocketing crew. Mahoney seems to have avoided depicting Sikes and other gang members in the illustrations for these later chapters, depicting a fugitive and embayed Bill Sikes without either signature white hat or canine companion in the rooftop scene, And creeping over the tiles, looked over the low parapet, putting this scene of the criminal mastermind facing execution on the morrow as the final plate and climax of his series of twenty-eight, his bandaged head and shrunken posture rendering him pitiable, if not completely sympathetic. One feels no such compassion for the condemned felon with the defiant, smouldering expression in the Furniss illustration. The shading of the figure and strong lines delineating his clothing and beard suggest a pent-up energy. As he stares at the reader, Furniss's Fagin is an enigma, for neither remorse nor reflection is immediately apparent. He is utterly alone as he dominates the confined space surrounding him, without associates and subordinates, or even furniture and a bible. His eyes shining "with a terrible light," Fagin in the Furniss illustration is both a haunted and a haunting presence, drawn with neither sentiment nor humour, but with savage intensity suggestive of a caged animal.

As Tony Lunch notes, Dickens had already employed Newgate as a setting in "A Visit to Newgate," the last of the "Scenes" section of Sketches by Boz, an essay especially written for the first collected edition of 1836. Dickens therein evokes the probable thoughts and feelings of three actual condemned prisoners: Robert Swan, convicted of armed robbery and subsequently reprieved, and two homosexuals, John Smith and John Pratt, who were hanged on the prison grounds on 27 November 1835. In novels after Oliver Twist, Dickens returned to Newgate, but only once to visit an inmate under sentence of death, Abel Magwitch in Great Expectations; however, whereas Fagin suffers execution, Magwitch cheats the system by succumbing to his injuries. "The Central Criminal Court — known as the Old Bailey — now cover the site of Newgate Prison" (Lynch 137), occupying Ludgate Hill.

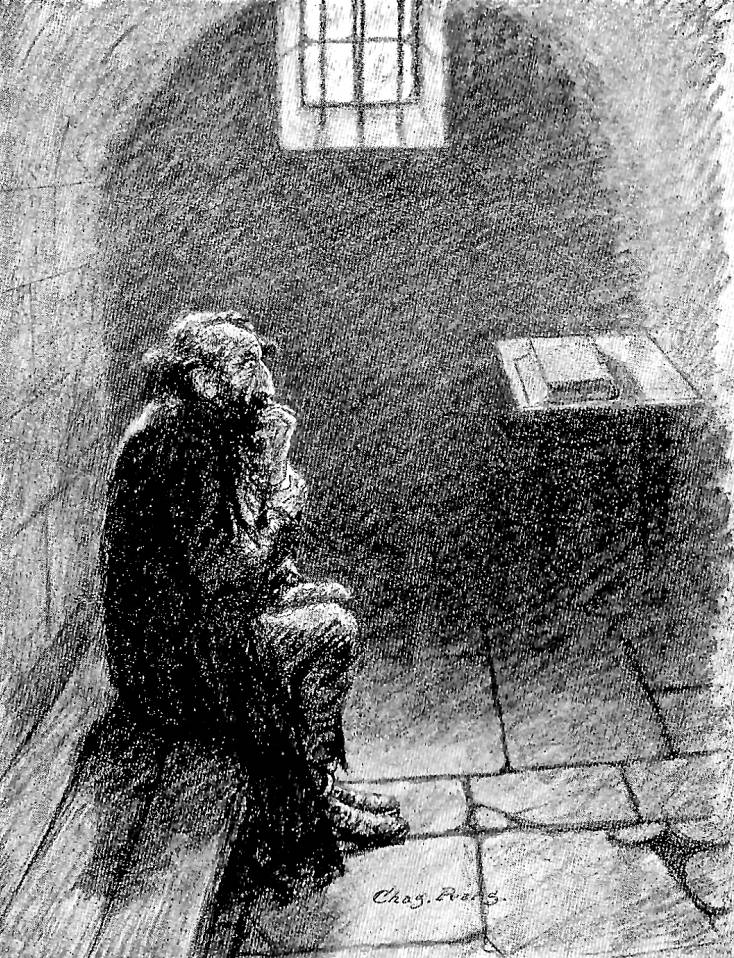

Left: Cruikshank's initial depiction of Fagin in Newgate, Fagin in the Condemned Cell (1838). Centre: Cruikshank's 1846 thumbnail of Fagin in prison, detail from the wrapper. Right: Charles Pears' Fagin (1912).

Cruikshank second and later conception of the incarcerated Fagin position him prominently at the centre bottom of the 1846 monthly wrapper contemplating his own death and — like Shakespeare's Richard the Third — the deaths of those who previously occupied the same cell, including some whose arrests he engineered. Beside him on the stone bench is his hat, seen in Cruikshank's earlier representations of Fagin. This representation appears to have influenced Mahoney's conception of the scene, for, although darkness is now beginning to engulf the cell, all is otherwise much the same as in the wrapper's vignette, including the hat on the bench, left, nearly lost in the darkness — and Mahoney does not show the barred window. The heavily shacked Fagin, however, is far more introspective and withdrawn in Mahoney's realisation. In neither the 1846 vignette nor the 1871 Household Edition study is there a Bible in the cell, nor even a table, as if Fagin is without even these simple objects for contemplation, and cannot avail himself of religious consolation, should he experience a last-minute spirituality. Since only after the moment captioned do the "Venerable men of his own persuasion . . . come to pray beside him" (200), the book is not likely a Hebrew Bible left by the rabbis whom Fagin subsequently dismisses "with curses." Furniss's version of this same scene, focussing on the glowing eyes of the prisoner, already "a snared beast" (412, Charles Dickens Library Edition), offers only minimal details of the cell: the shadow of the bars and the end of the stone bench. The condemned man is trussed up like a turkey, manacled at wrists and ankles, as in the Mahoney illustration. Although Charles Pears' figure (Waverley Edition, 1915) is likewise manacled, in the pencil drawing one is struck by Fagin's calm introspection — and his balding head, implying both age and thoughtfulness. No such touches of regret or even humanity occur in Furniss's rendition.

None of these illustrators, however, has deviated from the theme of the cheerless, minimally furnished cell that is the scene of the prisoner's last night as a living being. In contrast, historical pictures show the "Upper Condemned Cell" at Newgate, as in the Thomson painting of the preparations for the 1824 execution of forger Henry Fauntleroy, a partner in the bank Marsh, Sibbald and Co., as much larger and better lit. Even Luker'sThe Condemned Cell (1891) shows the cell as at least twice as wide, with two barred windows. However, a rare photograph dating from the 1890s shows a cell remarkably like Fagin's, although dating (apparently) from after the reforms of 1858, which occurred as a result of the political agitation of Elizabeth Fry:

It was in 1858 that the interior of Newgate Prison was re-built, on the single-cell system. Near the window of the cell shown above are the water-tank and basin; and in the right-hand corner is the bedding, neatly rolled up; on the shelf are the prisoner's Bible, prayer-book, plate, and mug, while in the foreground are his stool and the corner of the table. [http://www.peterberthoud.co.uk/2012/05/inside-newgate-prison/\]

Some 1,169prisoners met their deaths on the grounds of Newgate, one of the most celebrated inmates being Ikey Solomon (1787-1850), upon whom Dickens may have based the character of Fagin — although Solomon, a transported felon, died in prison in Hobart, Tasmania, and not in Newgate. Although as a result of thepublic campaign waged by such progressives as Charles Dickens, public executions on thegrounds were discontinued after 26 May 1868, private executions continued to be carried outon a gallows inside the prison walls. Closed in 1902, Newgate Prison was demolished in 1904. The Central Criminal Court (also known as "The Old Bailey" after the street on which it stands) now stands upon its site.

Bibliography

Benson, A. C. "Introduction" to Charles Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated byCharles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912. Pp. v-xiv.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980, 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1838; rpt. with revisions 1846.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 22 vols. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871. Vol. I.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. III.

_____. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The Waverley Edition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

_____.The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Graham Storey, Kathleen Tillotson, and Angus Eassone. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. I (1820-1839).

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. I, Book 2, Chapter 3.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Luker, W., Jr. "Newgate — The Condemned Cell," in W. J. Loftie,London City — Its History, Streets, Traffice, Buildings, People, 1891. http://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow/1859map/newgate\_prison\_a10.html

Lynch, Tony. "Newgate Prison, London." Dickens's England: An A-Z Tour of the Real and Imagined Locations. London: Batsford, 2012. Pp. 137-138.

McLenan, John, illustrator. "The placid look at the white ceiling came back, and passed away, and his head dropped quietly on his breast." Charles Dickens'sGreat Expectations. Harper's Weekly5: 27 July 1861: 447.

Kyd (Clayton J. Clarke). Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Pailthorpe, Frderick W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Vann, J. Don. "Oliver Twist." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985, 62-63.

Created 29 December 2014

Last modified 15 February 2020