"Mr. Pecksniff's Courtship" (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

"I am glad we met. I am very glad we met. I am able now to ease my bosom of a heavy load, and speak to you in confidence. Mary," said Mr. Pecksniff in his tenderest tones, indeed they were so very tender that he almost squeaked: "My soul! I love you!"

A fantastic thing, that maiden affectation! She made believe to shudder.

"I love you," said Mr Pecksniff, "my gentle life, with a devotion which is quite surprising, even to myself. I did suppose that the sensation was buried in the silent tomb of a lady, only second to you in qualities of the mind and form; but I find I am mistaken."

She tried to disengage her hand, but might as well have tried to free herself from the embrace of an affectionate boa-constrictor; if anything so wily may be brought into comparison with Pecksniff.

"Although I am a widower," said Mr Pecksniff, examining the rings upon her fingers, and tracing the course of one delicate blue vein with his fat thumb, "a widower with two daughters, still I am not encumbered, my love. One of them, as you know, is married. The other, by her own desire, but with a view, I will confess — why not? — to my altering my condition, is about to leave her father's house. I have a character, I hope. People are pleased to speak well of me, I think. My person and manner are not absolutely those of a monster, I trust. Ah! naughty Hand!" said Mr Pecksniff, apostrophizing the reluctant prize, "why did you take me prisoner? Go, go!"

He slapped the hand to punish it; but relenting, folded it in his waistcoat to comfort it again. [vol. 3, Chapter 30, "Proves That Changes May Be Rung in the Best-Regulated Families, and That Mr. Pecksniff was a Special Hand at a Triple-Bob-Major," pp. 99-100]

Commentary

In selecting his subjects for the four frontispieces for the four volumes in the American "Household Edition" of the early 1860s, Gilbert had merely to consider the original forty monthly illustrations by Dickens's graphic collaborator, Phiz, that is, Hablot Knight Browne. Among the incidents which occur within the scope of volume three (chapters 26 through 39), the farcical marriage proposal which the decidedly unromantic Seth Pecksniff makes to an obviously reluctant Mary Graham was an excellent choice for illustration because of its inherent physical conflict and ironic humour: that Pecksniff could ever love anybody but himself is patent nonsense, and that an intelligent young woman would find him desirable as a husband absurd. Moreover, the arboreal setting give the realist an opportunity to demonstrate his technical skill at depicting vegetation, the idyllic woodland setting serving to remind the reader of Mary's other lover, the devoted Martin, presently trapped in quite another sort of forest altogether.

However, Although he is successful at conveying both Mary's fashion sense, beauty, and reluctance, Gilbert does not rise to the comic possibilities that Dickens has offered him in Seth Pecksniff's sheer obtuseness. The persuasive voice and oily manner of the arch-hypocrite are inadequately presented in Gilbert's image of Pecksniff as a successful, well-dressed bourgeois of middle age. Although Gilbert's middle-aged professional man is self-assured, he is not funny, so that the reader delights more in the sheen of Mary's silk shawl than in Pecksniff's unconscious imitation of Satan accosting and attempting to seduce Eve in Paradise. Having achieved a satisfactory realisation of the glade in which Pecksniff encounters Mary, Gilbert has elaborated upon the text in terms of the figures' fashionable attire, but has almost entirely failed to realize the scene's verbal, physical, and character comedy. He does, however, set up expectations in the reader that Pecksniff's greed will induce him to pursue Mary romantically in hopes of ingratiating himself with Old Martin. The proleptic reading of the illustration does not include apprehensions about Mary's safety or the possibility of sexual violation, however, since to the reader already familiar with his character from volume one Pecksniff is hardly representative of the Victorian type known as the masher.

Whereas for chapter thirty-one, Phiz's twenty-fifth illustration (for the twelfth monthly instalment, December 1843), Mr. Pecksniff Discharges a Duty. . ., depicts the hypocritical Pecksniff discharging Tom Pinch with assumed hauteur and injured innocence, there is no plate in the original series which exploits the comic possibilities of showing Pecksniff in love — or, at least, his proposing to Mary. For such a scene, one must consult the Household Edition (1871-79) illustration for chapter thirty entitled (in an anticipation of French novel Marcel Proust, 1871-1922) Rustling among last year's leaves, whose scent woke memory of the past. . .; however, Fred Barnard does not specifically depict the meeting of Mary Graham and complacent, self-loving Pecksniff; rather, he satirically places a halo around the beaming, angelic countenance to expose his fatuousness. As is the case with Gilbert's 1863 illustration, Barnard frames the clerical-looking figure with copious shrubbery, but he does not suggest or imply Mary Graham's presence.

In the Diamond Edition of 1867, Sol Eytinge, Junior, depicts each character just once, so that Martin and Mark appear together as a team, and Pecksniff appears with his daughters Charity and Mercyrather than with Mary Graham, whom Eytinge pairs instead but quite plausibly with Old Martin, for whom she is both nurse and companion, in Old Martin and Mary. Appropriate to both the period and her social background, she wears more modest and less expensive clothing than Gilbert's harrassed heroine, but shares her intellectual gaze.

Since The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit was a nineteen-month serialisation, a sprawling narrative with a large cast of humorous characters, it was not especially well suited to Gilbert's sober and realistic style. However, with its caricatures directed at the exposure of hypocrisy on two continents and in two societies, it was the ideal vehicle for the comic genius and Expressionistic style of Dickens's last great Victorian illustrator, Harry Furniss. His studies of Seth Pecksniff in particular reveal the hyperbolic character's fatuous and self-aggrandizing nature, whether he is posturing before the crowd at the laying of the foundation stone in chapter thirty-five, asserting his leadership of the Chuzzlewits in chapter four, dismissing Tom Pinch in chapter thirty-one, or introducing his daughters to the recently arrived Young Martin in chapter five; in total, Furniss depicts the pious fraud seven times in twenty-nine illustrations in the Charles Dickens Library Edition. His most impressionistic and least detailed representation is Mr. Pecksniff Makes Lovein chapter thirty. The sheer energy of Furniss's pen communicates a power beyond what mere detail alone can communicate, so that Mary's discomfort amounting distaste effectively complements the leering, jowled visage of Pecksniff, who gazes upon her diminutive figure like a boa-constrictor upon its prey. To reinforce Dickens's description of Pecksniff as such a snake, her agitated skirt and shawl and the tree branches above her, in their sinuous movements suggest her entrapment by just such a creature.

In Gilbert's third frontispiece for the 1863 American edition of the novel, one has less sense of the comic possibilities in the almost photographic image of Pecksniff improbably "making love" and proposing to Mary than one receives in Furniss's handling of precisely the same subject.

Relevant Serial Edition (1843), Diamond Edition (1867), Household Edition (1873), and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910) Illustrations

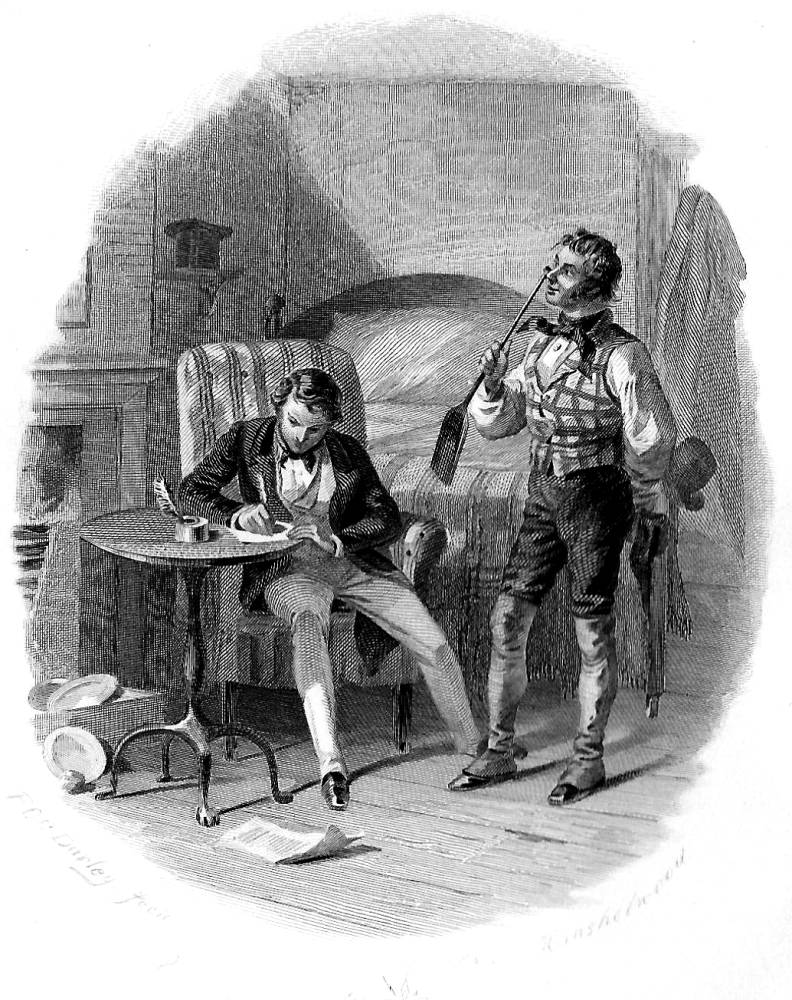

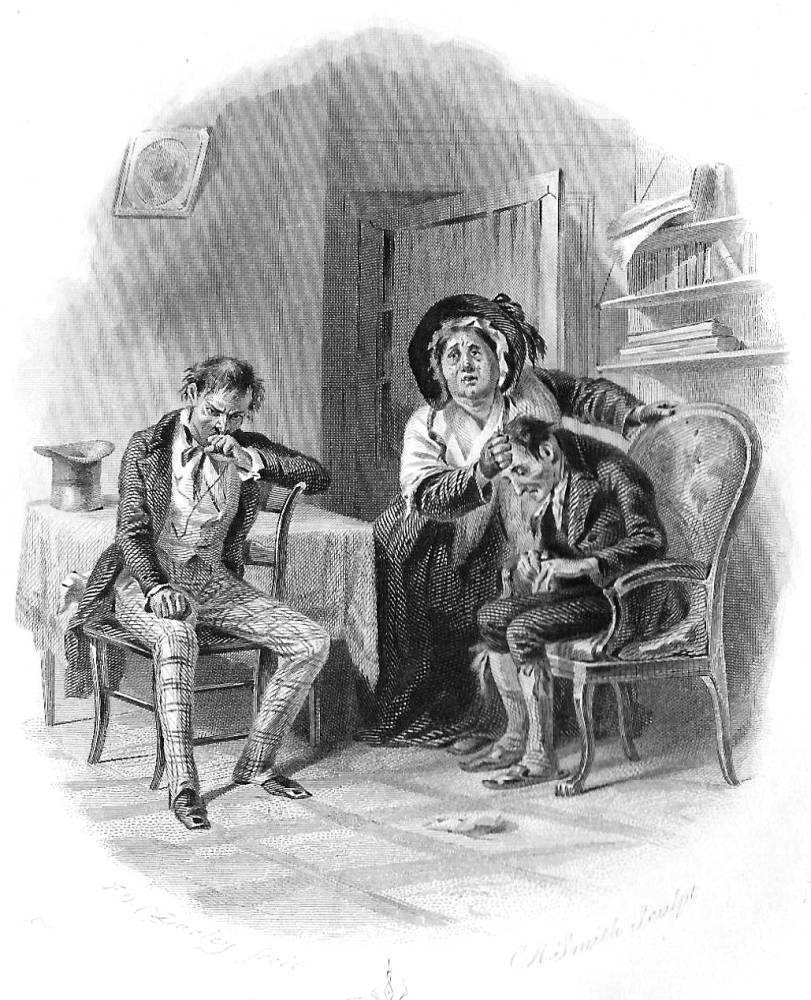

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's "Mr. Pecksniff Discharges a Duty Which He Owes Society" (February 1843). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s "Old Martin and Mary" (1867).

Later Editions. Left: Fred Barnard's "Rustling among last year's leaves, whose scent woke memory of the past, the placid Pecksniff strolled" (1872). Right: Harry Furniss's "Mr. Pecksniff Makes Love" (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Relevant Illustrations from the Other Frontispieces by Darley, 1863

Left: F. O. C. Darley's photogravure frontispiece for volume one representing the meeting of the novel's two greatest humbugs, the hypocritical architect, Seth Pecksniff, and the Chuzzlewit hanger-on and disgraced military officer, Montague Tigg, And was straightway let down stairs. Centre: Darley's frontispiece for volume two, "Jolly sort of lodgings," said Mark — Ch. 13. Right: Darley's photogravure for the frontispiece of volume four, <spanclass="tcartwork">"The creeter's head's so hot" said Mrs. Gamp. </spanclass="tcartwork">

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Il. Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

Dickens, Charles. Martin Chuzzlewit. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Il. F. O. C. Gilbert and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1863. Vol. 2 of 4.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Il. Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872. Vol. 2.

Dickens, Charles. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Il. Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

Last modified 13 March 2014