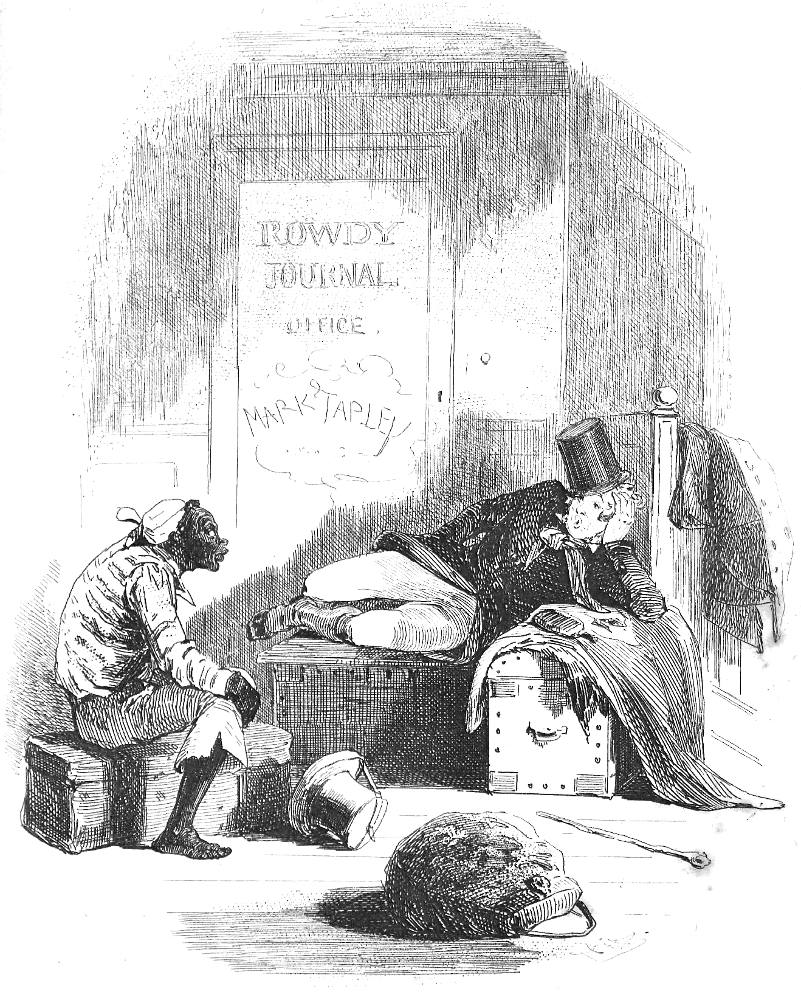

"Black and White" [An Incident in the Negro Car] by Marcus Stone for “American Notes” (1866) (original) (raw)

Passage Realised

This singular kind of coaching terminates at Fredericksburgh, whence there is a railway to Richmond. The tract of country through which it takes its course was once productive; but the soil has been exhausted by the system of employing a great amount of slave labour in forcing crops, without strengthening the land: and it is now little better than a sandy desert overgrown with trees. Dreary and uninteresting as its aspect is, I was glad to the heart to find anything on which one of the curses of this horrible institution has fallen; and had greater pleasure in contemplating the withered ground, than the richest and most thriving cultivation in the same place could possibly have afforded me.

In this district, as in all others where slavery sits brooding, (I have frequently heard this admitted, even by those who are its warmest advocates:) there is an air of ruin and decay abroad, which is inseparable from the system. The barns and outhouses are mouldering away; the sheds are patched and half roofless; the log cabins (built in Virginia with external chimneys made of clay or wood) are squalid in the last degree. There is no look of decent comfort anywhere. The miserable stations by the railway side, the great wild wood-yards, whence the engine is supplied with fuel; the negro children rolling on the ground before the cabin doors, with dogs and pigs; the biped beasts of burden slinking past: gloom and dejection are upon them all.

In the negro car belonging to the train in which we made this journey, were a mother and her children who had just been purchased; the husband and father being left behind with their old owner. The children cried the whole way, and the mother was misery's picture. The champion of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness, who had bought them, rode in the same train; and, every time we stopped, got down to see that they were safe. The black in Sinbad's Travels with one eye in the middle of his forehead which shone like a burning coal, was nature's aristocrat compared with this white gentleman. [Ch IX, "A Night Steamer on the Potomac River. Virginia Road, and a Black Driver. Richmond. Baltimore. The Harrisburg Mail, and a Glimpse of the City. A Canal Boat," 155-56]

Commentary: Dickens's Personal Observations of American Slavery

As Michael Slater explains in Charles Dickens (2009),

When it came to dealing with the unavoidable topic of slavery, which the manuscript of American Notes shows [Dickens] had originally fiercely broached in the first chapter set on American soil, the one dealing with Boston, he was disadvantaged by having spent such a short time in the South. In lieu, therefore, of incorporating into the narrative of his journey any first-hand 'sketch' of a scene in the slave states, or any account of the actual institution of slavery, Dickens deals with the subject in a chapter appended, as it were, to the narrative. This chapter is more of an anthology than anything else, consisting as it mainly does of advertisements for runaway slaves copied out by Dickens from an anti-slavery pamphlet by an abolitionist called Theodore Weld. These advertisements document the extreme brutality of the treatment experienced by such slaves, followed by a dozen extracts from Southern newspapers, supplied to Dickens by his publishers. . . . [Michael Slater, 200-201]

In fact, as Slater notes, Dickens found his single direct experience of slavery so "hateful" (185) that he abruptly changed his itinerary and, instead of going south to Charleston, travelled two thousand miles west to see the Looking Glass Prairie outside St. Louis, Missouri. He did, however, visit a tobacco factory staffed by slaves, as well as an actual slave-owner's plantation en route to Baltimore, Maryland.

Marcus Stone's Experience of the 1842 Travelogue

Born in 1840, Marcus Stone would not have been on hand to welcome the Dickenses home and hear first-hand of the writer's American experiences. However, with growing appreciation in the 1850s he would have read Dickens's writings of the 1840s, including the Christmas Book which his father illustrated in part, The Haunted Man(1848). As he began to receive commissions from Chapman and Hall after his father's death in 1859, Marcus would have discussed the texts upon which he was to work, including Great Expectations and American Notes, with Dickens in preparation for completing the wood-engravings for the Illustrated Library Edition. Thus, the illustrator would likely have been aware of the significance of the incident that Dickens witnessed in the Negro railroad car, for it was the author's only emotional engagement with the most negative aspects of slavery, and, along with the copyright controversy, did much to sour him on this Republic of the imagination. One wonders whether the entitling of this particular illustration was a collaborative effort as the issue of American slavery and particularly its place among the causes of the American Civil War would have been constantly in the press ("black and white") through Marcus Stone's formative years. For Dickens the book must have existed largely as an artefact of the 1842 American tour, but for Marcus it would have had a continuous relevance, and would have taken on new meaning when he received the illustrator's commission.

Dickens and Slavery on the 1842 American Tour

My heart is lightened as if a great load had been taken from it when I think that we are turning our backs on this accursed and detested system. I really don't think that I could have born it any longer (I, 410). Dickens to Forster, 21 March 1842, regarding Great Britain's having abolished slavery in its own dominions nine years earlier. [Cited in Adrian, 317]

The indignation of thirty-year-old Dickens, tourist and celebrity in ante-bellum America, is all too evident in his sarcasm about a matter that to Southerners seemed clear-cut, and was deeply entrenched in the economics of the plantation: slavery. By "black and white," Dickens's narrator may imply "a matter of good and evil" in which the Black mother, bereft of her husband, virtuously struggles to protect her children, and her vile White owner oggles her. Dickens communicated a similar abhorrence of the institution of slavery the following year in the American chapters of Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-44). Siding with the Abolitionists, Dickens employs sharp satire and withering sarcasm in defence of the American Negro, a life-long prisoner in a Republic in which, supposedly, all people were created equal, and are entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Although Marcus Stone as a child knew Dickens in the 1840s when his father Frank served as an illustrator for the Christmas Books, undoubtedly the great writer had communicated to his young illustrator for the Illustrated Library Edition his horror of slavery, and his great relief that the United States had at last outlawed the iniquitous practice in the midst of its Civil War.

The illustrator has made the slave-owner a troll, with gnarled features, and the mother, dressed very much in the middle-class, European fashion, protective of her children. The image therefore complements the economic blight of slavery upon the Virginia countryside by focussing on the relationship between the slave-owner and his property, a woman worthy of the reader's sympathy by virtue of the privation she is currently suffering and the lifetime's exploitation she is about to endure.

Some of his English friends, like Macready, who thought the book mean-spirited, wished that he had never written it. To his New England friends, the Dickensian combination of humor, severity, and idealism were admirably and effectively used to denounce slavery and materialism. To radical abolitionists, the main targets were well chosen, the tone appropriately condemnatory though in sufficiently serious. [Kaplan 152]

Stone's Illustrated Library Composition (1866)

One may complain of young Stone's illustration that in extending the text he has shown what Dickens could not possibly have seen from the outside of the railway carriage, for the illustrator has imagined the melodramatic plight of a wife and a mother without a protector or witnesses to her becoming the subject of a lustful owner's appropriating gaze. As a reminder of the economic arguments in favour of slavery in the United States up to President Lincoln's signing the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the illustrator has the mother sitting on a bale of cotton in the Negro car. The prosaic realism of the signage, the bale, and the woman's dress contrast the melodramatic pose as the mother tries to protect her children, and foil the grotesque caricature of a slave-owner whom Dickens has likened to one of the monsters from his childhood reading, The Voyages of Sinbad, the one-eyed cannibalistic giant of the third voyage in The Arabian Nights, which he had read in Cooke's fine-print Pocket Library series.

Relevant Illustrations, 1843-1872

Left: Hablot Knight Browne's depiction of an alderly former slave, Cicero, outside the offices of a New York paper, Mr. Tapley succeeds in finding a jolly subject for contemplation (Chapter 16, July 1843). Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s cartoon-like treatment of a Negro wagon-driver as a species of Black minstrel, The Black Driver (1867). Eytinge offers no interpretation of slavery or the American Negro in the novel. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: Fred Barnard's realisation of the Martin's meeting Cicero, "You're the pleasantest fellow I have seen yet," said Martin, clapping him on the back, "And give me a better appetite than bitters" (Household Edition, 1872).

References

Adrian, Arthur A. "Dickens on American Slavery: A Carlylean Slant." PMLA. 67.4 (June, 1952): 315-29.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. American Notes for General Circulation and Pictures from Italy in Works. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall: 1866, rpt. 1874.

_____. American Notes and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Bros., 1877.

_____. American Notes and Pictures from Italy. With eighteen illustrations by A. B. Frost and Gordon Thomson. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1844.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, with 59 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition, volume 2. London: Chapman and Hall, 1872.

_____. Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 7.

_____. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Kaplan, Fred. Chpter 5: "The Emperor of Cheerfulness (1842-1844)." Dickens: A Biography.New York: William Morrow, 1988. Pp.122-160.

Slater, Michael. Chapter 8: "America brought to book, 1842." Charles Dickens.New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009. Pp.175-206.

Last modified 8 January 2019