"On the Marshes, by the Lime-kiln" — ninth wood-engraving by Marcus Stone (1862) (original) (raw)

Passages Illustrated: A Brooding Atmosphere for the Curtain of Chapters LII and LIII

My heart was deeply and most deservedly humbled as I mused over the fire for an hour or more. The striking of the clock aroused me, but not from my dejection or remorse, and I got up and had my coat fastened round my neck, and went out. I had previously sought in my pockets for the letter, that I might refer to it again; but I could not find it, and was uneasy to think that it must have been dropped in the straw of the coach. I knew very well, however, that the appointed place was the little sluice-house by the limekiln on the marshes, and the hour nine. Towards the marshes I now went straight, having no time to spare. [Chapter LII, 486]

It was a dark night, though the full moon rose as I left the enclosed lands, and passed out upon the marshes. Beyond their dark line there was a ribbon of clear sky, hardly broad enough to hold the red large moon. In a few minutes she had ascended out of that clear field, in among the piled mountains of cloud.

There was a melancholy wind, and the marshes were very dismal. A stranger would have found them insupportable, and even to me they were so oppressive that I hesitated, half inclined to go back. But I knew them well, and could have found my way on a far darker night, and had no excuse for returning, being there. So, having come there against my inclination, I went on against it.

The direction that I took was not that in which my old home lay, nor that in which we had pursued the convicts. My back was turned towards the distant Hulks as I walked on, and, though I could see the old lights away on the spits of sand, I saw them over my shoulder. I knew the limekiln as well as I knew the old Battery, but they were miles apart; so that, if a light had been burning at each point that night, there would have been a long strip of the blank horizon between the two bright specks.

At first, I had to shut some gates after me, and now and then to stand still while the cattle that were lying in the banked-up pathway arose and blundered down among the grass and reeds. But after a little while I seemed to have the whole flats to myself.

It was another half-hour before I drew near to the kiln. The lime was burning with a sluggish stifling smell, but the fires were made up and left, and no workmen were visible. Hard by was a small stone-quarry. It lay directly in my way, and had been worked that day, as I saw by the tools and barrows that were lying about.

Coming up again to the marsh level out of this excavation, — for the rude path lay through it, — I saw a light in the old sluice-house. I quickened my pace, and knocked at the door with my hand. Waiting for some reply, I looked about me, noticing how the sluice was abandoned and broken, and how the house — of wood with a tiled roof — would not be proof against the weather much longer, if it were so even now, and how the mud and ooze were coated with lime, and how the choking vapour of the kiln crept in a ghostly way towards me. Still there was no answer, and I knocked again. No answer still, and I tried the latch. [Chapter LIII, 487]

Commentary: Atmosphere rather than Action

On opening the outer door of our chambers with my key, I found a letter in the box, directed to me; a very dirty letter, though not ill-written. It had been delivered by hand (of course, since I left home), and its contents were these: —

“If you are not afraid to come to the old marshes to-night or to-morrow night at nine, and to come to the little sluice-house by the limekiln, you had better come. If you want information regarding your uncle Provis, you had much better come and tell no one, and lose no time. You must come alone. Bring this with you.” [Chapter LII]

In reacting to the mysterious note, Pip determines to keep the engagement. The upshot will be his being attacked, tied up, and menaced by the letter's author, none other than Dolge Orlick in the lonely sluice-house, dimly seen to the right of the traveller. Behind the ruinous building is the Thames. Since he had probably not seen any of John Mclenan's forty illustrations for the novel when it appeared serially in Harper's Weekly (24 November 1860 through 3 August 1861), Marcus Stone had no precedents for illustrating the novel. Had he been inclined to hunt up a copy of the American periodical, Stone might have been surprised to discover that his American counterpart had not responded to the sensational events of Chapter LIII. Stone's notion behind the dark plate illustration of the Marshes in the moonlight appears to have been to create a suitably mysterious introduction for the deadly encounter about to occur rather than to show, dramatise, or realise the confrontation between the aggrieved Orlick and his unwitting victim, trussed up and ready to be sacrificed upon the altar of the displaced journey's bruised ego. Other nineteenth-century illustrators have made the other choice.

Other illustrations for this chapter showing the Captor and the Captive

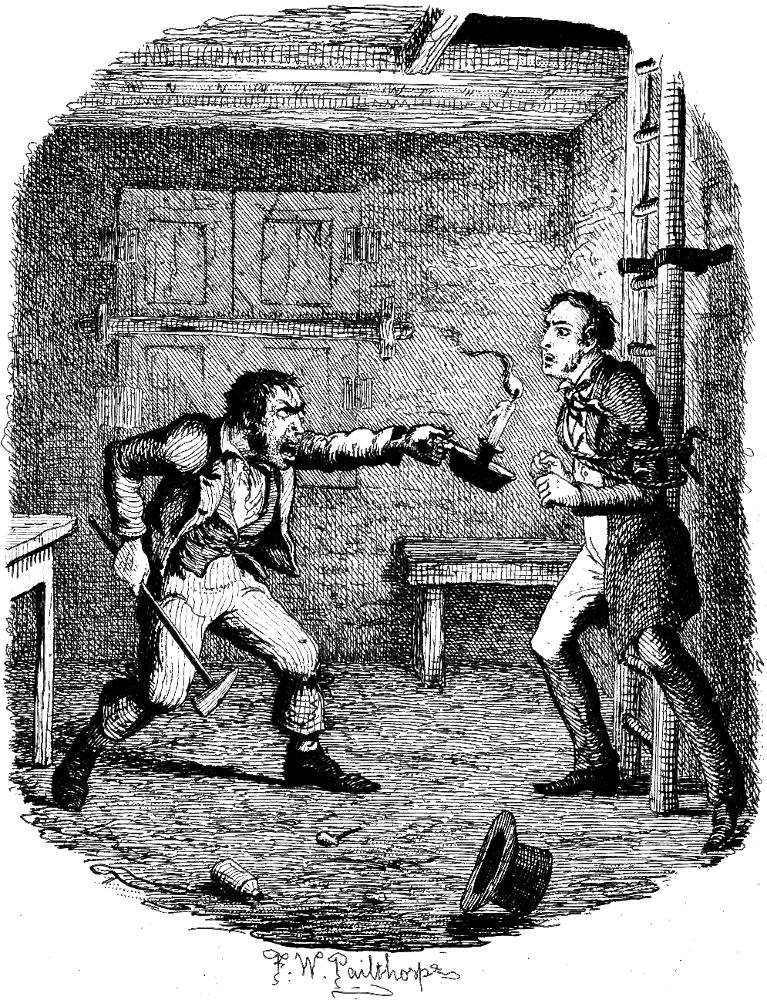

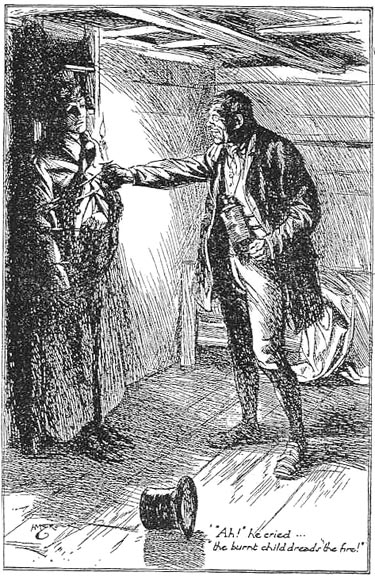

Left: Frederic W. Pailthorpe in the Robson & Kerslake edition creates a dramatic tension with raging Orlick's thrusting the candle into Pip's face in Old Orlick Means Murder (1885). Right: H. M. Brock in the Imperial Edition creates suspense with a cunning Orlick's calmly taunting his victim, in "Ah!" he cried . . . "the burnt child dreads the fire!"(1901).

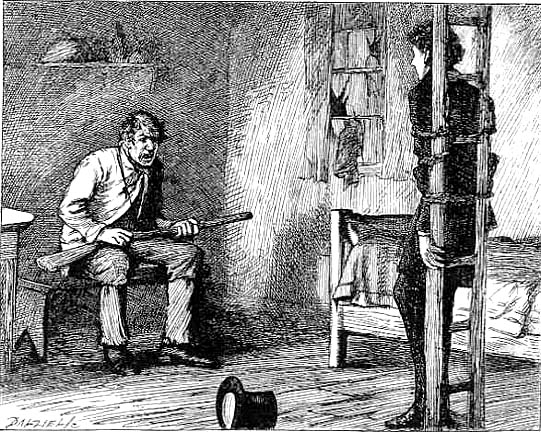

Whereas Harry Furniss in Pip in the Power of Dolge Orlick (1910) and Charles Green (1898) foreground Pip, trussed up on a ladder, the other 19th c. illustrators of the novel tend to focus on the sordid, lower-class Dickensian villain whose smouldering resentment has burst out like fire upon the powerless Pip. The Orlicks presented by Fraser (1876) and Pailthorpe (1885) do not seem intellectually equal to the task of ensnaring Pip, but the other representations are an interesting amalgam of cunning, ferocity, and intense rage.

Three Other Editions' Versions of the Orlick's Entrapment of Pip (1898-1898)

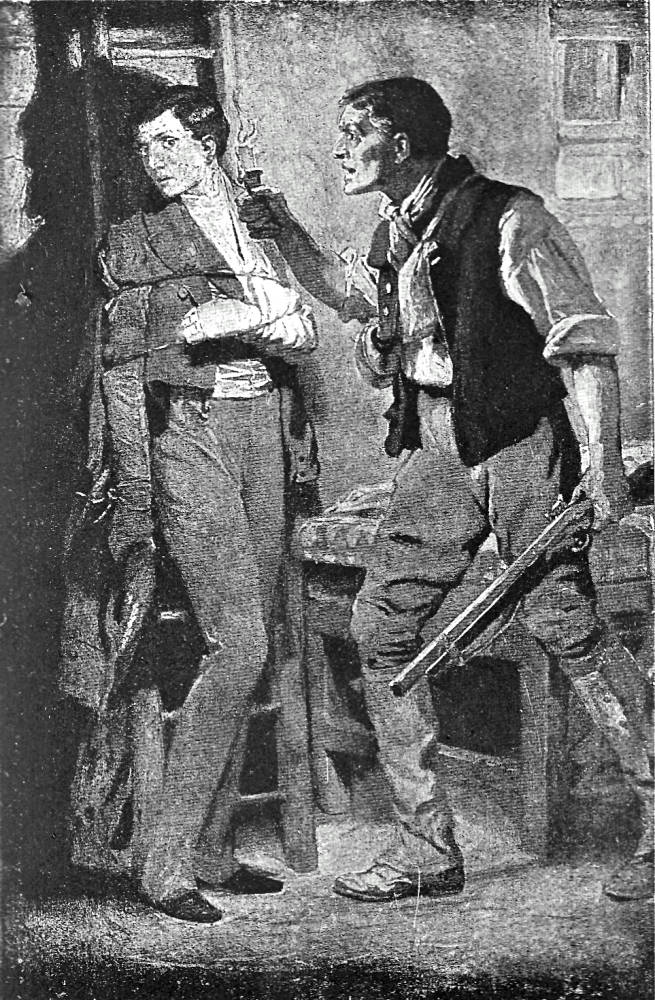

Left: A. A. Dixon's 1905 lithograph of Pip's entrapment by a younger Orlick: "Ah! the burnt child dreads the fire", in the Collins Clear-type Edition. Centre: F. A. Fraser describes the scene as if it were being enacted on stage: "Do you know this?" said he. in the Household Edition (1876). Right: Charles Green's lithograph of a younger Dolge Orlick's taunting the captured Pip: "Do you know this?" said he(1898).

Other Artists’ Illustrations for Dickens's Great Expectations

- Edward Ardizzone (2 plates selected)

- H. M. Brock (8 lithographs)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (2 lithographs from watercolours)

- Felix O. C. Darley (2 plates)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (8 wood engravings)

- John McLenan (40 wood engravings)

- F. A. Fraser in the Household Edition (1876) (30 wood-engravings)

- Frederic W. Pailthorpe (21 lithographs)

- Harry Furniss (28 plates)

- Charles Green (10 lithographs)

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Illustrations for Great Expectations in Harper's Weekly (1860-61) and in the Illustrated Library Edition (1862) — 'Reading by the Light of Illustration'." Dickens Studies Annual, Vol. 40 (2009): 113-169.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Vol. 9 (1859-1861).

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. All the Year Round. Vols. IV and V. 1 December 1860 through 3 August 1861.

Dickens, Charles. ("Boz."). Great Expectations. With thirty-four illustrations from original designs by John McLenan. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson (by agreement with Harper & Bros., New York), 1861.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Il. Marcus Stone. The Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1862. Rpt. in The Nonesuch Dickens, Great Expectations and Hard Times. London: Nonesuch, 1937; Overlook and Worth Presses, 2005.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities andGreat Expectations. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Volume 6 of the Household Edition. Il. F. A. Fraser. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. The Gadshill Edition. Il. Charles Green. London: Chapman and Hall, 1897-1908.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. "With 28 Original Plates by Harry Furniss." Volume 14 of the Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

McLenan, John, il. Charles Dickens's Great Expectations [the First American Edition]. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, Vols. IV: 740 through V: 495 (24 November 1860-3 August 1861). Rpt. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson, 1861.

Rosenberg, Edgar (ed.). "Launching Great Expectations." Charles Dickens's Great Expectations. New York: W. W. Norton, 1999. Pp. 389-423.

Stein, Robert A. "Dickens and Illustration." The Cambridge Companion to Charles Dickens. Ed. John O. Jordan. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2001. 167-188.

Watt, Alan S. "Why Wasn't Great ExpectationsIllustrated?" The Dickens Magazine Series 1, Issue 2. Haslemere, England: Euromed Communications, 2001: 8-9.

Waugh, Arthur. "Charles Dickens and His Illustrators." Retrospectus and Prospectus: The Nonesuch Dickens. London: Bloomsbury, 1937, rpt. 2003. Pp. 6-52.

Created 12 January 2014

Last modified 1 November 2021