"Mr.Bumble and Mrs. Corney" by Charles Pears — second illustration for "The Adventures of Oliver Twist" (1912) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated: Mrs. Corney has "all the chinks" (as Shakespeare would say)

"The tea was made, and handed in silence. Mr. Bumble, having spread a handkerchief over his knees to prevent the crumbs from sullying the splendour of his shorts, began to eat and drink; varying these amusements, occasionally, by fetching a deep sigh; which, however, had no injurious effect upon his appetite, but, on the contrary, rather seemed to facilitate his operations in the tea and toast department.

"You have a cat, ma'am, I see," said Mr. Bumble, glancing at one who, in the centre of her family, was basking before the fire; "and kittens, too, I declare!"

"I am so fond of them, Mr. Bumble, you can't think," replied the matron. "They're so happy, so frolicsome, and _so_cheerful, that they are quite companions for me."

"Very nice animals, ma'am," replied Mr. Bumble, approvingly; "so very domestic."

"Oh, yes!" rejoined the matron with enthusiasm; "so fond of their home too, that it's quite a pleasure, I'm sure."

"Mrs. Corney, ma'am," said Mr. Bumble, slowly, and marking the time with his teaspoon, "I mean to say this, ma'am; that any cat, or kitten, that could live with you, ma'am, and not be fond of its home, must be a ass, ma'am." [Chapter 23, "Which contains the substance of a pleasant conversation between Mr. Bumble and a lady; and shews that even a beadle may be susceptible on some points," p. 128]

Commentary: A mature "romance" motivated by property considerations

Dickens regards Mrs. Corney and Mr. Bumble as irresponsible public servants who exploit positions of trust for personal gain. For Dickens poetic justice is ultimately served by placing the couple ass inmates into the workhouse they had once administered. They are justly punished for attempting to suppress the truth of Oliver's birth by secreting the locket that belonged to his mother. If one may make a modest criticism of Pears' amiable, middle-aged couple it is simply that they are too amiable, too attractive, albeit somewhat self-centred, as well they ought to be as agents of the 1834 New Poor Law. Moreover, those readers accustomed to the detailism of Cruikshank and Phiz must have taken issue with the lack of context for the figures as the bare wall, ornamented only with striped wallpaper, contains no portraits, and the furnishings of the parlour, indications of Mrs. Corney's affluence, are minimalised.

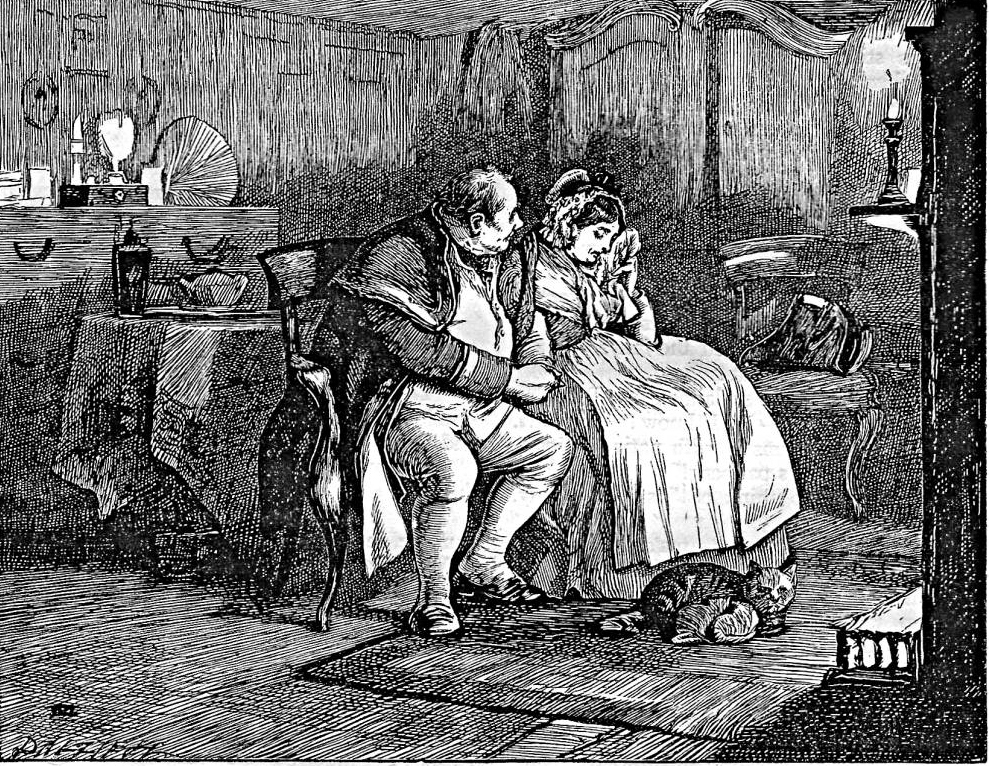

Although George Cruikshank seventy-four years earlier took obvious delight in depicting the budding romance of the middle-aged parish beadle and the workhouse matron, having already depicted the self-satisfied humbug inOliver Escapes Being Bound Apprentice to the Sweep (Part 2, March 1837), he does repeat the felicity. With an eye for the grotesque, Cruikshank must have found the notion of the courtship of Mrs. Corney by the arrogant, ridiculous Bumble irresistible, a scene which he echoed in the domestic romance of Charlotte and Noah Claypole,Mr. Claypole as he appeared when his master was out (Part 12, March 1838), in which Bumble plays a minor role, peering in at the window. Cruikshank in both instances undercuts the romance by the leering, smirking faces of the would-be lovers. The problem with Pears' reinterpretation is not with the properties, which are exactly as Dickens's text specifies — Pears has even positioned a bottle of port behind Bumble, on the chest of drawers. However, one does not receive the perspective of Mr. Bumble that Mrs. Corney is affluent, a good catch from a materialistic standpoint. Rather, Pears, with an eye for beauty, even in the middle-aged, makes her physically attractive and pleasant; clearly, as Bumble learns to his cost, she is neither compliant nor comfortable.

Cruikshank expands Dickens's description of the pair's mutually flirtatious behaviour by focussing on a mother cat and three kittens romping on the carpet, before the fire, their frisky behaviour an analogue for that of amorous Bumble and simpering Mrs. Corney. And, of course, the cats suggest the sexual dimension of the scene that the writer of the early Victorian period could not directly address, although Cruikshank's animated beadle does not seem especially "tender" in his appreciation of the widow. The bottles of freshly decanted port for the infirmary sit on Mrs. Corey's sideboard, but are not likely to be transferred to the sick ward. An astute touch is Cruikshank's suggesting Mrs. Corney's vanity by the portrait of her hanging above the sideboard — one might have expected a portrait of the long-deceased Mr. Corney. And perhaps a hint of the entrapment of Bumble in an unhappy marriage is given in the birdcage hanging from the ceiling, above the fireplace. Although other illustrators have given the cats a place of prominence, they must have seemed too sentimental a touch to Charles Pears, for they are not in evidence in his treatment of the tea-drinking scene in Mrs. Corney's well-appointed parlour — not nearly so lavishly furnished in Pears' plate.

Illustrators since Cruikshank have also enjoyed to varying degrees the opportunity for visual satire that the pompous Bumble presents. Sol Eytinge, Junior, in the 1867 Diamond Edition volume that Dickens himself may very well have perused on his second American reading tour, depicts Bumble in full uniform as he presents the comely widow with the bottle of port, although the dual study lacks the amorous overtones of the original Cruikshank plate. In contrast, Household Edition illustrator James Mahoney has realised the same parlour and mature figures, but has transformed the playful cats into tranquil felines dozing before the fire as Mr. Bumble prepares to propose to the widow, who is tearfully considering her single marital status. In Mahoney, sentiment has unfortunately replaced humour, as Bumble in this 1871 illustration seems genuinely concerned about the lachrymose widow (when in fact he has just scrutinized her silverware and china). However, whereas in 1910 Harry Furniss reinjected the humorous element and the playful cats in his visual satire of the corpulent agents of the Poor Law, Pears dismisses the satirical note almost entirely.

Pears and Mahoney versus Cruikshank: Realism versus Caricature

In what ways, then, is Pears' reinterpretation of or an improvement over the parallel illustrations of Cruikshank and Mahoney? Pears conveys a sense of the couple of hypocrites, depicting them as enjoying their tea and (supposedly) each other's company, even as the materialistic beadle casts an envious glance at Mrs. Corney's furnishings. Pears depicts them real people rather than as Cruikshankian caricatures. Although he includes such indications of comfortable affluence as the padded chairs, the tea service, and the lace-topped chest-of-drawers, Pears does not clutter the composition with the bric-a-brac to which early Victorian taste usually ran in such a room for entertaining, the front parlour. His figures are intelligible as he conveys by their postures and expressions both their characters and relationships, while he uses their clothing to imply their social status. Moreover, there is not a trace of that all too Victorian failing, sentimentality, which dominates Mahoney's otherwise realistic treatment of the beadle and his future wife. In other words, Pears' revision of the tea-drinking scene is completely consistent with the changing tastes and attitudes of the fin de siecle, even if the dual study fails to convey much about Dickens's criticism of their egotism, veniality, and hypocrisy.

Illustrations from the original serial publication and later editions (1867-1910)

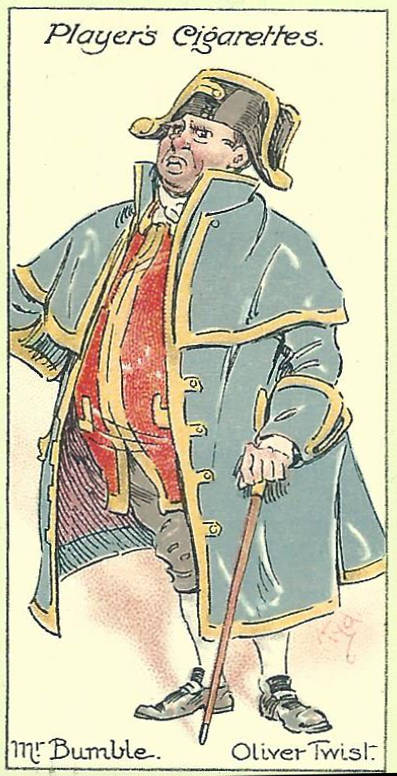

Left: George Cruikshank's Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney taking tea. Centre: Sol Eytinge, Junior's Mrs. Corney and Mr. Bumble. Right: Kyd's extra illustration (1889) Mr. Bumble.

Left: Kyd's Player's cigarette card no. 3, Mr. Bumble (1910). Centre: Harry Furniss's Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney from the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910). Right: F. W. Pailthorpe's study of Mr. Bumble's dancing a jig as he contemplates controlling all of Mrs. Corney's property by marrying her: Inexplicable conduct of Mr. Bumble when Mrs. Corney left the room (1886).

Above: James Mahoney's 1871 wood-engraving of the fatuous beadle consoling the tearful matron of the workhouse, "Don't sigh, Mrs. Corney."

Related Material

- Depictions of Bumble, the Parish Beadle from Oliver Twist, and other Beadles

- Some Discussions of Oliver Twist

- Oliver Twist as a Triple-Decker

- Oliver untainted by evil

- Like Martin Chuzzlewit, it agitates for social reform

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Clarke, J. Clayton. The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London: Raphael Tuck, 1890.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House and Graham Storey. The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1965. Volume One (1820-29).

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. Illustrated by James Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 3.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Intro. by A. C. Benson. Works of Charles Dickens. The CentenaryEdition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Edited by B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Kyd. Characters of Charles Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Pailthorpe, Frederic W. (Illustrator). Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist. London: Robson & Kerslake, 1886. Set No. 118 (coloured) of 200 sets of proof impressions.

Created 21 March 2015

last updated 1 December 2021