"'My dear Captain Ravender,' says he. . . . " by E. G. Dalziel —

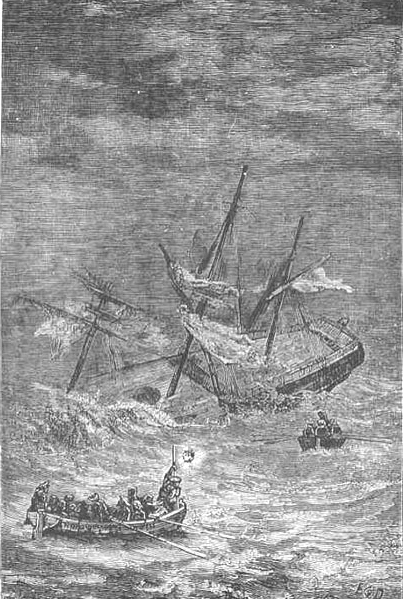

illustration for "The Wreck," Chapter 1 in The Wreck of 'The Golden Mary' in "Christmas Stories" (1856) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

It is, personally, neither Smithick, nor Watersby, that I here mention, nor was I ever acquainted with any man of either of those names, nor do I think that there has been any one of either of those names in that Liverpool House for years back. But, it is in reality the House itself that I refer to; and a wiser merchant or a truer gentleman never stepped.

"My dear Captain Ravender," says he. "Of all the men on earth, I wanted to see you most. I was on my way to you."

"Well!" says I. "That looks as if you were to see me, don't it?" With that I put my arm in his, and we walked on towards the Royal Exchange, and when we got there, walked up and down at the back of it where the Clock-Tower is. We walked an hour and more, for he had much to say to me. He had a scheme for chartering a new ship of their own to take out cargo to the diggers and emigrants in California, and to buy and bring back gold. Into the particulars of that scheme I will not enter, and I have no right to enter. All I say of it is, that it was a very original one, a very fine one, a very sound one, and a very lucrative one beyond doubt.

He imparted it to me as freely as if I had been a part of himself. After doing so, he made me the handsomest sharing offer that ever was made to me, boy or man & mdash; or I believe to any other captain in the Merchant Navy — and he took this round turn to finish with . . . .["The Wreck," p. 30]

Commentary

Dalziel, perhaps not wanting to telegraph too much of the plot of the framed tale, has chosen one of the 1856 Christmas number's less consequential moments inThe Wreck of 'The Golden Mary', Being the Captain's Account of the Loss of the Ship, and the Mate's Account of the Great Deliverance of her People in an Open Boat at Sea. Here, the Liverpool merchant quite by chance meets Merchant Navy Captain William George Ravender in front of a marine chandler's shop in Leadenhall Street, London. There is little in Dalziel's characterization that suggests that either figure is that of a sea-faring man, so that the nature of the discussion and Ravender's background are both communicated through the contents of the display in the store window behind him.

The artist for the 1868 Illustrated Library Edition, E. G. Dalziel, chose a moment more consonant with the temper of the opening chapter, the only part that Dickens himself wrote. Charles Dickens, in the throes of writing the nineteen-month serial novelLittle Dorrit and readying the melodrama The Frozen Deep for production in his Tavistock House home theatre, was more than usually busy in the autumn of 1856, the time of the year when he customarily created his annual Christmas story for his weekly journal, for whereas the culmination of his autumn activities was usually the "Extra Christmas" number, here it would be a play upon which he had been collaborating with Collins and in which he would star as the self-sacrificing Richard Wardour:

Dickens's current preoccupations were many: he was more than half-way through writing Little Dorrit, running Household Words (whose new year's volume was due out the next day [i. e., 3 January 1857], featuring the first number of Wilkie Collins's The Dead Secret), overseeing building works at his newly-acquired house at Gad's Hill, dealing with the management of the drainage and gas supply to Miss Coutts's refuge for homeless women atUrania Cottage in West London, and rehearsing and overseeing the preparations — costumes, props, sets, music, invitations and seating arrangements for the many guests clamoring to attend — for his production of at Tavistock House, just poised for its dress-rehearsal [on 5 January 1857]. [Richardson, 183-184]

In consequence of his being so pressed for time that fall, Dickens unfortunately left the illustrators of the volume editions of Christmas Stories, who restricted themselves to realising only those portions of the framed stories which Dickens himself wrote, less scope than for the other seasonal offerings. This framed story for the "Extra Christmas" number of 1856, then, was largely the product of Dickens's journalistic collaborators, notably the upcoming novelist and Dickens protegé Wilkie Collins, who provided most of John Steadiman's testamentary document (signalled by the heading "All that follows, was written by John Steadiman, Chief Mate") in "The Wreck," as well as the seventh and final part, "The Deliverance." Young newcomer Percy Fitzgerald (1834-1925) contributed "The Armourer's Story" and "The Supercargo's Story," Harriet Parr (publishing under the pseudonym "Holm Lee") "Poor Dick's Story," Adelaide Anne Procter "The Old Seaman's Story," and the Reverend James White "The Scotch Boy's Story." Unfortunately the various volume editions of Christmas Storiesdo not contain anything other than Dickens's and Collins's work, so that later readers have little sense of the original publication context, and must have wondered how the survivors of the wreck were finally rescue — rescued they must be, or the loquacious Captain would not be able to provide his account.

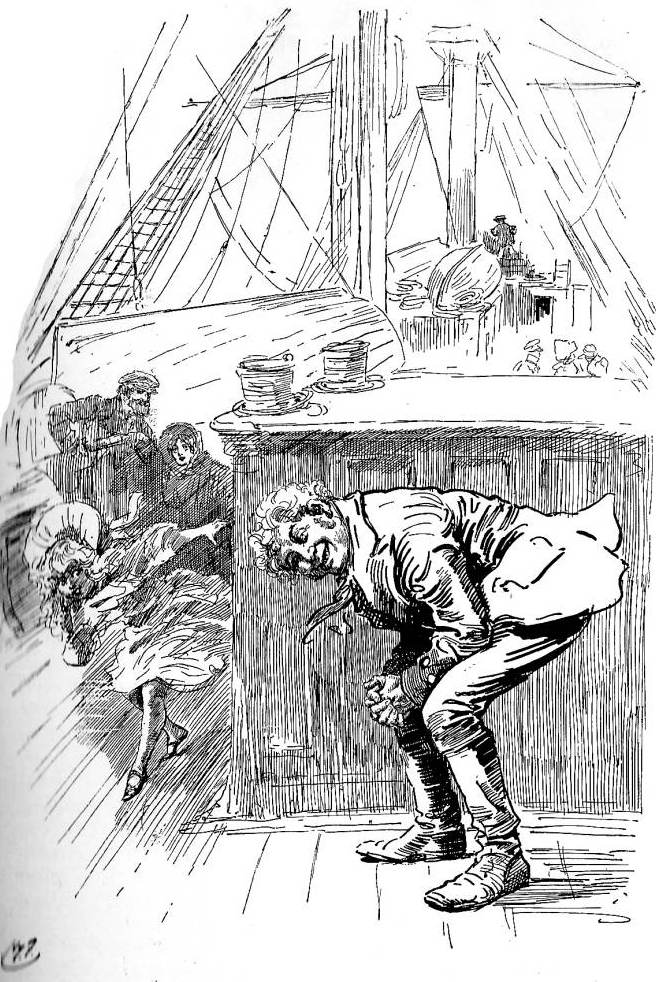

In the Illustrated Library Edition (1868) Edward Dalziel depicted high seas and the imperilled ship, whereas Furniss's impressionistic rendering of the comic and touching scene between the First Mate (John Steadiman) and Golden Lucy on deck is highly dynamic as vivacious child plays hide-and-seek and a jovial Steadiman deliberately looks the wrong way as others on deck enjoy the fun. The Household Edition's realisation, in contrast, involves a Liverpool shipping magnate's hiring Captain Ravender to navigate the treacherous seas that lie between England and the goldfields of California. Dalziel's somewhat prosaic meeting of the merchant and the sea captain for the Household Edition volume is not satisfying in that it contributes far less to the reader's understanding of the text than Furniss's 1910 picture or even Dalziel's own 1868 illustration of the wreck. The pair meet by chance in front of a marine store shop in Leadenhall Street, London; the realisation is neither especially imaginative nor particularly engaging, and the two middle-class figures (despite a difference in height) look so alike that one cannot really determine which is the loquacious mariner and which the maritime capitalist. In this instance, Dalziel's backdrop is of greater visual interest than his foreground.

Relevant Illustrated Library (1868) and Charles Dickens Library Edition (1877) Illustrations

Left : E. G. Dalziel's "The Wreck of the 'Golden Mary'". Right: Harry Furniss's 1910 illustration "The Golden Lucy." [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books and The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 10.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller and Additional Christmas Stories. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Junior. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All The Year Round". Illustrated by Townley Green, Charles Green, Fred Walker, F. A. Fraser, Harry French, E. G. Dalziel, and J. Mahony. The Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1868, rpt. in the Centenary Edition of Chapman & Hall and Charles Scribner's Sons (1911). 2 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Stories from "Household Words" and "All the Year Round". Illustrated by E. G. Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller, Hard Times, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Il. C. S. Reinhart and Luke Fildes. The Household Edition. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller. Illustrated by E. G. Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Richardson, Ruth. "Death & The Lady: Miss Coutts, Mr. Dickens & The Dead House Committee." Dickens Quarterly, vol. 30, No. 3 (Sept., 2013): 177-197.

Scenes and characters from the works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gordon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition.". New York: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Copy in the Robarts Library, University of Toronto.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. "Christmas Stories." The Oxford Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 100-101.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and The Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Last modified 21 April 2014