"'John Barsad,' the Spy" — Furniss's seventeenth illustration for "A Tale of Two Cities" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Complemented

It was remarkable; but, the taste of Saint Antoine seemed to be decidedly opposed to a rose on the head-dress of Madame Defarge. Two men had entered separately, and had been about to order drink, when, catching sight of that novelty, they faltered, made a pretence of looking about as if for some friend who was not there, and went away. Nor, of those who had been there when this visitor entered, was there one left. They had all dropped off. The spy had kept his eyes open, but had been able to detect no sign. They had lounged away in a poverty-stricken, purposeless, accidental manner, quite natural and unimpeachable.

"JOHN," thought madame, checking off her work as her fingers knitted, and her eyes looked at the stranger. "Stay long enough, and I shall knit "BARSAD" before you go."

"You have a husband, madame?"

"I have."

"Children?"

"No children."

"Business seems bad?"

"Business is very bad; the people are so poor."

"Ah, the unfortunate, miserable people! So oppressed, too — as you say."

"As you say," madame retorted, correcting him, and deftly knitting an extra something into his name that boded him no good. [Book Two, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Sixteen, "Still Knitting," 170]

Commentary

The illustration corresponds to two distinct passages: in the first, Madame Defarge records the description of the ancien regime spy assigned to Saint Antoine to flush out members of the Jacquerie; in the second, the spy enters the Defarges' wine-shop — in their curious customer Madame Defarge recognizes Barsad from the description leaked to her by the secret society's mole at police headquarters. Because the illustration has reference to two passages, editor J. A. Hammerton has not provided the usual explanatory quotation. Previously, in the crowded Old Bailey courtroom scene captured by Hablot Knight Browne in The Likeness, the government witnesses Roger Cly and John Barsad must be present (as is Jerry Cruncher, immediately behind Sydney Carton, centre), but Phiz has certainly not made his presence obvious. Consequently, in the original monthly sequence of illustrations, the reader had to wait until the September issue to see in The Wine-shop (see below) a realisation of this slippery, long-faced but otherwise undistinguished figure who sells his investigative talents to the government of the day. An informant inside the police office had alerted the Defarges of a newly appointed royalist spy, for whom he had provided the St. Antoine publicans with an accurate physical description:

"Good day, madame," said the new-comer.

"Good day, monsieur."

She said it aloud, but added to herself, as she resumed her knitting: "Hah! Good day, age about forty, height about five feet nine, black hair, generally rather handsome visage, complexion dark, eyes dark, thin, long and sallow face, aquiline nose but not straight, having a peculiar inclination towards the left cheek which imparts a sinister expression! Good day, one and all!" [169]

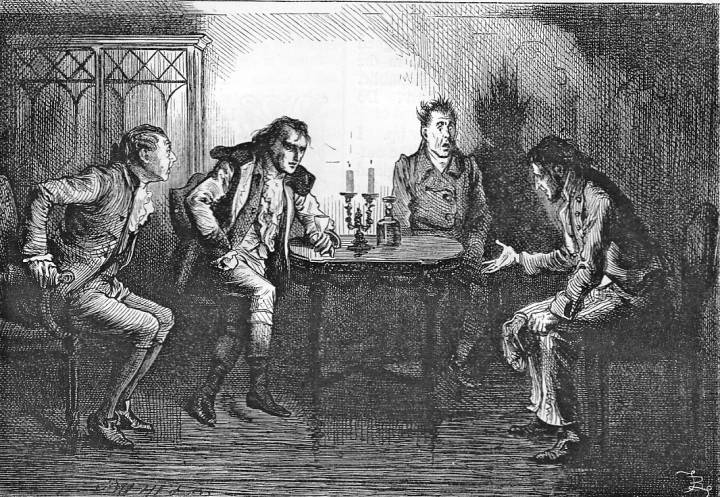

When we meet Barsad again in the original narrative-pictorial sequence, in The Double Recognition, his clothing is unchanged, despite the fact that he is now "The Sheep of the Prisons" (a specialist in gleaning information from prison-house conversations) for the Revolutionary regime. Furthermore, Phiz does not reveal his face, leaving him a shadowy figure whom Dickens uses to facilitate the escape of Charles Darnay from La Force.

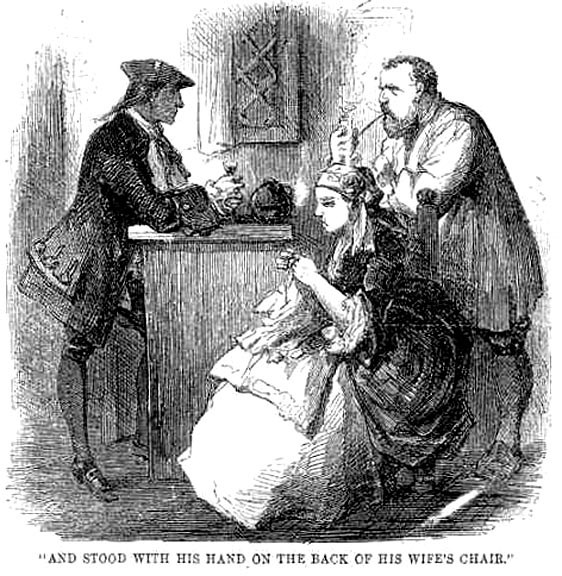

The fifteenth weekly instalment in Harper's, issued on the 13th of August 1859, features John McLenan's less animated and detailed realisation of the scene in the wine-shop, And stood with his hand on the back of his wife's chair for Book Two, Chapter 16, "Still Knitting." Again, the illustrator does not particularize the spy, who great talent is to blend in rather than stand out. Although McLenan probably had no recourse to Phiz's monthly illustrations, he has imagined the spy in much the same garb, although his stockings are dark rather than light, as in Phiz's illustration. McLenan, however, throws his figure into the shade, as if deliberately obscuring his facial features. The American serial artist throws the light available (presumably from the open door) upon the faces of the Defarges, and renders the spy's figure somewhat smaller in perspective.

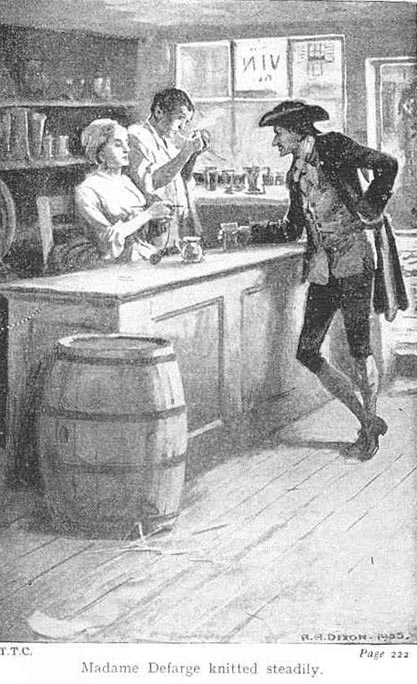

In the September 1859 illustration by Phiz, The Wine-shop (see below), Phiz has also placed the emphasis on the knitting Madame Defarge, whereas McLenan's scene has a divided focus since the caption points to Defarge as the principal figure whereas the Barnard wood-engraving, dropped into the text of the Household Edition volume of 1874 has situated Madame Defarge at its centre. However, Barnard in his version of The Wine-shop seems far more interested in the three "Jacques" opposite the placid proprietess, who has laid her knitting aside to pick her teeth as she listens intently to the trio. Barnard depicts Madame Defarge on a number of occasions, but his parallel wood-engraving, Saint Antoine, does not represent Madame Defarge in the context of her business; moreover, Barnard does not reveal the figure of Barsad, bearded and in a greatcoat of the latest style, until very late in his sequence, Here Mr. Lorry became aware, from where he sat, of a most remarkable goblin shadow on the wall (see below), the illustration for Book Three, Chapter 8 — the twentieth large-scale wood-engraving in his sequence of twenty-five. Again, Barnard has chosen to place the spy in the shadows, but has naturalised him, making him a plausible presence: here is the man who knows how the system operates, Barnard implies.

Furniss's Barsad, like Phiz's, is dressed as a solid bourgeois of the period, in respectable black and unremarkable clothing. But whereas Phiz's figure is unremarkable, except, perhaps, for a rather long nose and nutcracker physiognomy, Furniss's much more realistic study conveys something of the subject's personality and attitude. Here is a confident observer of the human play who is somewhat cynical about his values and allegiances. Although Furniss does not present the Anglo-French spy Solomon Pross (alias "John Barsad") in the context of the wine-shop, he particularizes the chameleon-like agent of whatever political faction is in power. His Barsad has a knowing, almost supercilious look, as if he is taking the reader-viewer into his confidence. This is one of the few Furniss images in volume 13 not accompanied by any sort of explanatory quotation, other than that the artist and editor suggest that his name, appearing in quotation marks, is an assumed rather than a birth-name, and therefore an apellation not to be given much credence. Only much later, of course, will his sister reveal Barsad's true identity, but Furniss has opted not to attempt to provide a version of Phiz's The Double Recognition. Furniss's spy appears without any informing background or other characters, as if the illustrator is implying the spy's adaptability. This is, in fact, Barsad's only appearance in Furniss's narrative-pictorial sequence; however, the knowing spy's regarding the viewer with such scrutiny and attitude renders this sole appearance memorable. Barsad here emerges from the shadows momentarily, but he is, according to the accompanying text, being scrutinized in every particular, including the "sinister expression" (169) that Dickens mentions, and a certain swagger implied by the placement of his hands. As in his second appearance in Phiz's original illustrations, we do not see Barsad "straight on," but from the back.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities(1859) — the last Dickens's novel "Phiz" Illustrated

- Costume Notes on A Tale of Two Cities

- List of Plates by Phiz for the 1859 Monthly Instalments

- John McLenan's Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Eight Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (1874)

- A. A. Dixon's Illustrations for the Collins Pocket Edition of A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

Relevant Illustrations from earlier editions, 1859, 1867, 1874, and 1905.

Left: John McLenan's version of Phiz's illustration of Barsad in the wine-shop, And stood with his hand on the back of his wife's chair. Right: Phiz's "The Wine-shop" (September 1859).

Left: Fred Barnard's "Here Mr. Lorry became aware, from where he sat, of a most remarkable goblin shadow on the wall" (1874). Right: Dixon's wine-shop proprietors coolly assess the government spy in Madame DeFarge knitted steadily (1905). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1988.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974. IX (1859-61).

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. All the Year Round. 30 April through 26 November 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. 7 May through 3 December 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities andGreat Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Mengel, Ewald. "The Poisoned Fountain: Dickens's Use of a Traditional Symbol in A Tale of Two Cities." Dickensian, 80/1 (Spring 1984): 26-32.

Sanders, Andrew. A Companion to "A Tale of Two Cities." London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

Created 26 November 2013

Last modified 9 January 2020