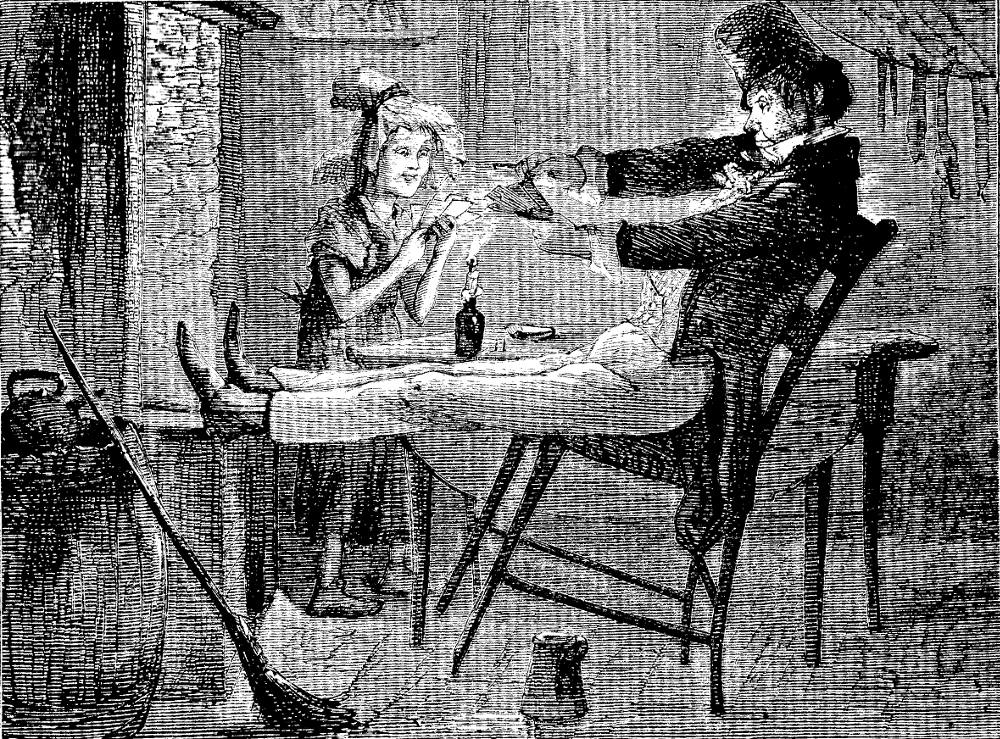

"The Marchioness" by "Phiz" — Extra Illustration for "The Old Curiosity Shop" (1848) (original) (raw)

Commentary: Workhouse Cinderella

"Now," said Mr. Swiveller, putting two sixpences into a saucer, and trimming the wretched candle, when the cards had been cut and dealt, ‘those are the stakes. If you win, you get ‘em all. If I win, I get ‘em. To make it seem more real and pleasant, I shall call you the Marchioness, do you hear?" [Chapter 57, 120]

Dickens introduces the Marchioness in Chapter 34, when she arrives at Dick's door to announce that, as the Brasses' new law clerk, it is his responsibility to show the vacant room to and stipulate the rental terms for a potential tenant. Dickens then has her reappear for a meagre supper administered by her shrewish employer, Sally Brass, in Chapter 37, which is the subject of Furniss's initial illustration of child-servant in the oversized milkmaid's bonnet and slippers, Dick Swiveller hears the Marchioness say "No". At this point, the seventy-two chapter novel is nearly half-over, and Furniss has completed two-thirds of his narrative-pictorial sequence. For Dickens, the Brasses' "small servant" seems to have been an afterthought, whom he introduced late in the action as necessary plot mechanism to reveal Quilp's plot to have Kit Nubbles sentenced to two years' transportation for a crime he did not commit, the theft of a five-pound note from the office of Sampson Brass. Subsequently, thanks to her habit of listening to her employers' conversations through the key-hole, she proves instrumental in securing Kit's release.

Commentary: The Real Marchioness: The Woman whom the Small Servant became

In "Phiz's Marchioness" (1966) Michael Steig argues that the 1848 extra-illustration of this fascinating character is not merely Phiz's re-thinking of "the small servant" as an attractive and sensitive young woman. Rather, he argues, the picture reflects Dickens's interpretation of a character he once considered making the illegitimate child of Daniel Quilp and Sally Brass.

For although the first two illustrations in which the Marchioness appears ("Mr. Brass at the Keyhole" (see below), Ch. 35, and "The Small Servant's Dinner" (see below), Ch. 36) show her clearly as a child, those depicting her after she and Dick become acquainted are oddly varied. In "The Marchioness at Cards" (Ch. 57, fig. I, see below) she has a small, childish body and an old woman's face; in her particular clothing she resembles nothing so much as a stereotyped figure of a witch. In the next relevant illustration, the one in which Dick awakes to find her moved into his rooms ("A Quiet Game of Cribbage", Ch. 64, fig. II), the Marchioness is dressed in the same outfit — tall milkmaid's bonnet, oversized slippers, and butcher's apron over her dress — but her neck and shoulders are bare, her face is much less haglike, and there is perhaps even a hint of a bosom. In the two other illustrations in which she appears ("The Marchioness in the Chaise", Ch. 65, fig. III; and "Delicacies for Mr. Swiveller", Ch. 66, fig. IV), the Marchioness's face looks more natural still. Descriptions must be somewhat subjective, but I think it is safe to say that Browne is trying to depict a face that is basically feminine, and definitely more than childish, but whose attractiveness has been marred by privation. In the first of this pair of engravings the Marchioness's face has a determined look that makes her seem a combination of child and woman; in the second, in which her expression is joyful, she appears decidedly adolescent [Steig, "The Marchioness," 144]

Steig draws our attention to a number of embedded details in the 1840 steel-engraving (particularly the trunk, the medicine-bottle, and the playing cards) to support his contention that this is not a version of Mrs. Richard Swiveller, but a fresh representation of the Marchioness as she develops in the novel over the course of a year:

On her face is an open expression quite different from the haunted, ravaged look of the original illustrations. One's first thought is that this must be the Marchioness after she has gone to school and married Dick;but the details belie this impression, for she sits on a chestmarked "D. Swiveller His Chest", and holds several playing cards in her lap, while two medicine bottles are visible inthe background. These details indicate that this is an illustration of that part of the novel in which the Marchioness nurses Dick through his illness and plays cribbage with herself to while away the time. (It corresponds to "A Quiet Game of Cribbage", in which, perhaps coincidentally the Marchioness looks most feminine.) There is no ambiguity here: the Marchioness is explicitly nubile, andyet, according to the setting, is "small servant" and not polished nineteen-year-old. Phiz has compensated for the uncertainty of his early illustrations with the directness ofthis one. Indeed, he overcompensates by eliminating allsigns (except the untidy hair and the oversized slippers) ofthe Marchioness's privation, and to that extent he distortsDickens. But the illustration as a whole may be taken to represent part of the artists's imaginative experiencing of Dickens's creation, a part which is given only fleeting and hesitant expression in the original engravings. [145]

Six Illustrations in the Original 1840 Serial Depicting the Marchioness

- Mr. Brass at the Keyhole (Chapter XXXV)

- The Small Servant's Dinner (Chapter XXXVI)

- The Marchioness playing Cards (Chapter LVII)

- A Quiet Game at Cribbage(Chapter LXIIV)

- The Marchioness in the Chaise(Chapter LXV)

- Delicacies for Mr. Swiveller(Chapter LXVI)

Relevant illustrations from other editions, 1867-1924

Right: Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s dual character study of one of Dickens's oddest couples, Dick Swiveller and The Marchioness (1867).

Thomas Green chose to end his length series of illustrations for the American Household Edition of the novel with the married life of the Swivellers, depicting the formerly androgynous Small Servant as the charming young woman Sophronia: Upon every anniversary Mr. Chuckster came to dinner(1872).

Charles Green's less whimsical Household Edition illustration focuses on Dick's response to seeing the Marchioness at his bedside in The Marchioness jumped up quickly, and clapped her hands (1876), and the cribbage board is not evident.

Left: Clayton J. Clarke's amusing caricature of the dirty-faced, preternaturally old workhouse child in the Player's Cigarette card series: The Marchioness (Card No. 28, 1910). Right: Harry Furniss's study of the Marchioness inserted into Chapter 47, well before she quits the Brasses to nurse Dick. Furniss depicts her as a pensive waif in The Marchioness (1910), a Cinderella with a disreputable broom, a pail, and a water-jug.

Left: A watercolour version in which Kyd emphasizes her Eliza Doolittle, adolescent features in The Marchioness, dating from 1910. Right: Harrold Copping's realisation of the same scene in Character Sketches from Dickens (1924).

Related Resources Including Other Illustrated Editions

- The Old Curiosity ShopIllustrated: A Team Effort by "The Clock Works" (1841)

- Cattermole's Illustrations of The Old Curiosity Shop.

- Frontispieces to the three-volume edition of Dickens's The Old Curiosity Shop, illustrated by Felix Octavius Carr Darley in the James G. Gregory (New York) Household Edition (1861-71)

- The Old Curiosity Shop by Sol Eytinge, Jr., in the Boston Diamond Edition (1867)

- The Old Curiosity Shop by Thomas Worth in the American Household Edition (1874)

- The Old Curiosity Shop by Charles Green in the British Household Edition (1876)

- The Old Curiosity Shopby W. H. C. Groome in the Collins' Clear-Type Press Edition (1900)

- The Old Curiosity Shop by Harry Furniss in the British Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (13 lithographs from watercolours)

- Harold Copping (2 plates selected)

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Old Curiosity Shop in Master Humphrey's Clock. Illustrated by Phiz, George Cattermole, Samuel Williams, and Daniel Maclise. 3 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1841. Rpt., 1849 by Bradbury and Evans (3 vols. in 2).

Steig, Michael. "Phiz's Marchioness." Dickens Studies. 2, 3: (September 1966): 141-46.

_______. Chapter 3. "From Caricature to Progress: Master Humphrey's Clock to Martin Chuzzlewit." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 53-85.

Created 5 July 2002

Last modified 11 September 2020