Hanko - 99% Invisible (original) (raw)

The Tokyo rail and metro systems make up one of the largest rapid transit networks in the world. More than 14 billion people walk through its turnstiles every year. That’s about 40 million rides every single day. On a typical morning during rush hour, commuters stand cheek to jowl in cramped train cars.

But last year, at the start of the COVID epidemic, after the Japanese government declared a state of emergency, the trains emptied out. Most, but not all. At the height of the pandemic, many people still found themselves commuting on a daily basis, and not just in the metro, and not just to one place.

Many of these people had to take the risk because they needed documents to be stamped with hanko. Hanko, sometimes called insho, are the carved stamp seals that people in Japan often use in place of signatures. Hanko seals are made from materials ranging from plastic to jade and are about the size of a tube of lipstick.

Photo by Angie from Sawara, Chiba-ken, Japan

The end of each hanko is etched with its owner’s name, usually in the kanji pictorial characters used in Japanese writing. This carved end is then dipped in red cinnabar paste and impressed on a document as a form of identification. Hanko seals work like signatures, only Instead of signing on a dotted line, you impress your hanko in a small circle to prove your identity. But unlike a signature, which you can make with any old pen or touch screen, in Japan you need to have your own personal hanko with you whenever you stamp something, and you have to stamp it in person.

Photo by maletgs (CC BY SA 2.0)

There is also not just one kind of hanko. You might have one cheap hanko you carry in your bag every day, and another fancy one stored in a safe deposit box that you might only use once or twice in your life. There’s also just something undeniably cool about the act of impressing a hanko onto a document. But even most Japanese have gotten to the point where they are fed up with the whole hanko system. So how did Japan get here? Two decades into the 21st century, why do the Japanese still need to use this ancient, analog thing?

The History of Hanko

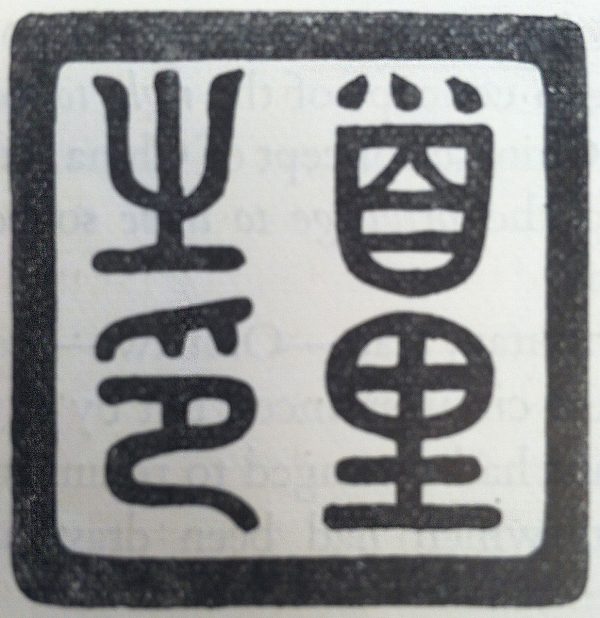

Hanko didn’t use to be everywhere in Japan. In fact, they weren’t even originally Japanese. “The earliest seal is known to have gone from China to Japan… apparently, it was given by the Chinese emperor of the time and that dates to … the year 57 A.D.” explains Philip Hu, curator of Asian art at the St Louis Art Museum and an expert in East Asian seals. Hu says the earliest hanko were status symbols used by the likes of emperors, court officials, and samurai. They were made of materials like soapstone and jade and were engraved using seal script, a form of calligraphic writing. But they were not the kind of thing you saw every day.

Seal of the Ryuku Kingdom. Photo by George Kerr.

Most ordinary people in Japan only had given names – or what in the west might be called first names. If you did have a surname, it was usually shared with your entire community. Only members of the feudal aristocracy had the kind of specific family names that you might put on a hanko. And starting in the 1600s, Japan’s shogun rulers imposed a policy of strict international isolation, cutting Japan off from the rest of the world and effectively preserving this feudal system. So even as late as the 19th century, most people in Japan didn’t really use seals, or need them.

“Onko Azuma no hana” Flowers of Edo in Old Times “Shogun-ke Fukiage ni oite Kuji jocho no zu” Shogun hearing a lawsuit at Fukiage (of Edo Castle). Toyohara Chikanobu (1838-1912)

But in 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry arrived in Japan, demanding that the country open up trade with the rest of the world. The arrival of Perry‘s fleet kicked off a period known as the Meiji restoration in which Japan transformed itself into a modern, industrialized nation-state. The old feudal system of the shogunate was done away with, and replaced with a centralized state bureaucracy which proceeded to change almost everything about how society was structured.

Commodore Matthew Perry

In order to do any of that effectively, the new bureaucratic regime needed to make one additional change. Everyone in Japan would have to choose surnames. Before the Meiji restoration, most people in Japan didn’t have family names. Or they might share a name with their entire community. But the new state bureaucracy needed a better way to keep track of who was who, so in 1875, a law was passed requiring every citizen to register a surname. But it wasn’t enough that everyone have their own unique(ish) name. In this new modern Japan, everyone now also needed their own hanko. Suddenly, hanko went from rarefied status symbols to something that almost everyone had, because they had to. And soon, seal manufacturing became its own major industry.

Eventually, there came to be three different types of hanko, depending on the context. There was the regular, everyday hanko called a mitome-in; the ginkgo-in, which was used for banking; and the jitsu-in which in English means a person’s “actual seal” or their “real seal.” Jitsu-in were not used very frequently, but instead reserved for the most important kinds of documents in a person’s life. It was kind of like having a social security number, if your social security number could only be written down in one place, and had immense sentimental value.

A Traditional Practice for a Modern Era

In time, almost every element of government, business, and social life was systematized and put onto paper, usually stamped with one of these three hanko, but Hanko would come to play an even more visible role in Japanese life in the 20th century thanks to a business practice called nemawashi.

Nemawashi can be thought of as a consensus-building procedure. It means laying the groundwork for any big decision by lobbying and consulting with everyone involved prior to moving forward—meaning if you have an idea, you first have to approach those concerned, one by one, discuss your plan, and get buy-in from each of them individually. Hanko comes in because as you move through the company, from the lowest ranks to the highest, once someone understands and agrees with your idea, they impress their hanko on the document to show their consent.

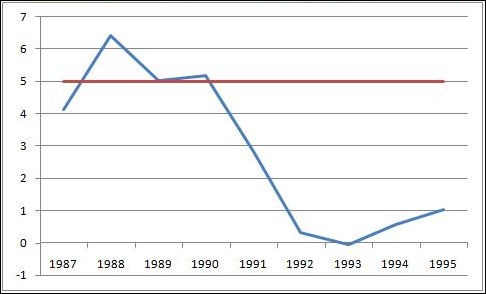

For a long time, nemawashi was simply how business worked in Japan. It was a culture of consensus, in which everyone at a company took on risks and rewards together — and it was often credited with Japan’s incredible economic growth in the mid 20th century. As nemawashi’s most visible symbol, the use of hanko went unquestioned, but that would start to change in the 1990s.

Hanko Meets The Internet

From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, Japan experienced a severe recession. That widespread anxiety had a profound effect on the practice of nemawashi, because it had been easy enough to stamp your approval on a business plan during the boom years when most plans worked. But once the economy spiraled, the risks of stamping your hanko on something multiplied, and workers at Japanese firms were increasingly hesitant to move forward on any plan at all. As a result, many companies got stuck in bureaucratic quagmires.

And if that wasn’t bad enough, this all happened at the same time that the internet was taking off, and a tradition requiring people to stamp paper documents using special seals to be physically carried on their person at all times wasn’t exactly internet-friendly.

If anything, the hanko has shackled Japan to the old paper system. Needing to physically stamp things disincentivizes people from ever digitizing documents since it’s only a matter of time until you’d have to print any given document back out just so it can be stamped.

When things like PDFs and digital signatures first appeared in the 1990s, many people in Japan expected that a “digital transformation” was just around the corner, but it never really happened. And, ironically, that’s in part because of the slowness of nemawashi and the hanko system. If you want your company or institution to stop using hanko, your first have to make sure everyone signs off on the new model … with a hanko.

The End of an Era?

Lately, it seems as if the cultural tide may have finally turned. Some large Japanese corporations have been quietly retiring their hanko in recent years. Younger generations of Japanese people who have no memory of the pre-internet boom years are using hanko less.

And now the same state bureaucracy that created the modern hanko system might have no choice but to kill it.

When COVID first hit, there was a sense that Japan would be spared the worst of it, and could keep doing business as usual. But that didn’t last long. Instead, the pandemic finally did what years of bureaucratic stagnation could not. Stories of hanko procedures forcing people to brave train cars in the middle of a lockdown have finally spurred the government to act. In May 2021, the administration of Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga enacted a set of laws establishing a new agency to speed up the process of digitization, and many believe the government move is a watershed moment.

Still, there have been some who want to hold onto the old ways. They worry that an end to hanko also marks an end to the country’s culture of consensus and shared responsibility in favor of a more western model based on individual accomplishment. One regional assembly has officially opposed the government’s move to phase out hanko, and a group of lawmakers in the national parliament recently formed a coalition to preserve them, kinda like a “Seal Appreciation Caucus”.

Farewell

On the edge of the entertainment and shopping area of Shinjuku in western Tokyo, there is a small Buddhist temple dedicated to Bishamonten, one of the seven lucky gods of Japanese folklore. This past October, a priest knelt by the temple’s altar, rang a bowl bell, and chanted a sutra behind a plastic face shield. He was performing a memorial service for a batch of about fifty hanko, brought to the temple by a group of nearby office workers.

It’s not uncommon for inanimate objects to receive funeral rites in Japan. They’re a way to bid farewell and commemorate items that have served their purpose and are no longer needed, like scissors, sewing needles, and… hanko. In fact, October 1st is Seal Day, when hanko shops throughout the country hold memorial services for old retired seals. But at the temple in Shinjuku, there was a distinct sense that this funeral was different, and that this time, it wasn’t only these individual hanko to which Japan was saying goodbye.