Online Lesson: African Americans in the Spanish Civil War | The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives (original) (raw)

By: William Loren Katz,Fraser M. Ottanelli, Christopher Brooks

“Why I, a Negro, who have fought through these years for the rights of my people, am here in Spain today? Because if we crush Fascism here, [we] will build us a new society–a society of peace and plenty. There will be no color line, no jim-crow trains, no lynchings. That is why, my dear, I am here in Spain.”

– Canute Frankson to my dear friend, Albacete, Spain, July 6, 193

Before Spain

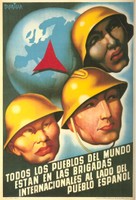

In a little-remembered prelude to World War II, a small group of African Americans, together with 40,000 men and women from 53 nations, traveled thousands of miles to defend the legally elected Spanish republican government against a military uprising backed by Fascist and Nazi dictators. Among these international volunteers were 2,800 idealistic men and women who left the United States to become “The Abraham Lincoln Brigade.” About ninety of these, including two women, were African Americans. They sailed from a land where discrimination was custom, segregation the law of the land, and lynchings were still common. What made more than seven-dozen African Americans sail to a distant land to fight world fascism?

Following World War I, large numbers of African Americans embraced radical ideologies. This new militancy among U.S. blacks was a response to decades of unrelenting, brutal oppression. In 1896 the Supreme Court ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson that segregation did not violate the Constitution. Conditions were slightly better in the North but patterns of racism and exploitation restricted African Americans to unskilled jobs and forced them to live in crowded neighborhoods.

After World War I, U.S. Blacks confronted once again the forces of white supremacy and a revitalized Ku Klux Klan. Yet the appearance of a Communist government in Russia in 1917 opened new vistas for African American militancy. After Lenin’s Communist party came to power in the Soviet Union and boldly proclaimed “the wretched of the earth” should rule the world, African American resistance took on new meaning. In Chicago, an African Blood Brotherhood led by Cyril Briggs talked of arming Black men for self-defense and called for unity with white workers to overthrow capitalism and imperialism. In 1924 Briggs led his followers into the U.S. Communist party.

Other African Americans also turned to the Communist party for inspiration and organizational support. The most significant African American Communist of this early era was World War I veteran Harry Haywood. During the 1920s Haywood headed for the Soviet Union. In 1928 at a Comintern conference he embraced a proposal that Blacks who lived in the sixty contiguous southern U.S. counties (where they accounted for a majority of the population) be entitled to self-determination including the right to secede from the United States. Such ideas became the basis of the Communist party’s organizing among southern Blacks during the 1930s. Haywood later served briefly as a commissar in the Lincoln Brigade.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s Black militants were increasingly drawn into the U.S. Communist party. With the slogan “Black and white unite and fight!” Communists took up issues affecting African Americans such as the struggle for self-determination in the South and resistance to lynchings and other forms of oppression. In Black neighborhoods Communists gained support when white “comrades” helped families evicted from their homes.

The event that solidified black support for the Communist party was the Scottsboro Case of 1932. Confronting an obvious example of racial injustice in Alabama, Communists provided legal assistance for nine young Black men falsely accused of raping two white women.

Other political struggles of the 1930s politicized African Americans who would later serve in Spain. For James Yates interracial unity against racism and economic exploitation became a reality during a march of unemployed workers in Chicago:

Suddenly I felt as one with these people, Black and white.

I was part of their hopes, their dreams, and they were part of mine.

And we were part of a larger world of marching poor people …

We were millions. We couldn’t lose. My throat swelled with pride.

African Americans also perceived Italian imperialism as a threat to world peace. In 1935 Benito Mussolini, seeking a new Italian empire in Africa, launched an invasion of Ethiopia. African Americans in New York and Chicago organized a “Hands off Ethiopia” campaign. The African American poet and journalist Langston Hughes, who later served as a journalist during the Spanish Civil War, wrote “The Ballad of Ethiopia” that included these words:

All you colored peoples

Be a man at last

Say to Mussolini

No! You shall not pass

As fascist aggression stirred the African American community, Blacks and whites joined to collect relief supplies. Some trained for military action. In New York, where a thousand men drilled, Salaria Kea, a nurse at Harlem Hospital, collected funds for a 75-bed hospital for the Ethiopian front. W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson addressed a “Harlem League Against War and Fascism” rally and A. Philip Randolph linked the invasion to “the terrible repression of Black people in the United States.” An anti-fascist rally in Chicago organized by Communists Harry Haywood and Oliver Law was banned and the mayor sent 2,000 police to disperse a crowd of ten thousand.

African Americans were also becoming aware that Nazi racial views spelled death for the world’s people of color. “I had read Hitler’s book, knew about the Nuremberg laws,” recalled Vaughn Love, a volunteer from Harlem in New York City, “and I knew if the Jews weren’t going to be allowed to live, then certainly I knew the Negroes would not escape and that we would be at the top of the list. I also knew that the Negro community throughout the United States would be doing what I was doing if they had the chance.”

By May 1936 when Mussolini’s army had occupied Ethiopia, only two African Americans pilots are believed to have reached the front. But ten weeks later when Mussolini’s troops joined Franco’s assault in Spain, African Americans saw an opportunity to strike back. In Chicago, James Yates and his friend Alonzo Watson concluded “Ethiopia and Spain are our fight” and prepared to leave for Spain.

Many African Americans saw Franco’s military rebellion in Spain as an extension of Mussolini’s aggression against Africa and of the fight against Jim Crow and hard times in the United States. For Vaughn Love, “fascism is the enemy of all black aspirations” and he could not wait to “get to the front and kill these Fascists.” In Spain, Oliver Law told a journalist, “We came to wipe out the fascists; some of us must die doing that job. But we’ll do it here in Spain, maybe stopping fascism in the United States too, without a great battle there.”

Some Black recruits brought unusual skills to the fight against fascism. In 1937 when the United States only had five licensed African American pilots, two of them, James Peck and Paul Williams, volunteered to challenge the Fascists’ air mastery. In the United States they held commercial licenses but found their careers frustrated. In Spain they found action. Another African American, Dr. Arnold Donowa, a Harvard graduate and noted Harlem dental surgeon, brought his surgical skills. As head of the Medical Corps’ Oral Surgery Unit, he often operated without “a drop of Novocain” and “a lack of instruments and supplies needed for adequate jaw surgery. And frequently we had not even enough gauze and bandages to dress the wounds of the men.” Albert Chisholm, arrived in Spain from Washington where he had drawn political cartoons for the Northwest Enterprise, a Seattle African American newspaper. Chisholm gladly contributed his work to the International Brigade newsletter, Our Fight. Burt Jackson was a skilled mapmaker at Fifteenth Brigade headquarters.

The Spanish Civil War also stirred broad humanitarian concerns. Nurse Salaria Kea joined 70 other American women who volunteered to serve in Spain’s hospitals.

The War in Spain

In defiance of the U.S. State Department’s order “NOT VALID FOR SPAIN” stamped on passports, African Americans and their white comrades had to enter Spain illegally. They sailed to France pretending to be tourists and then crossed the border into Spain. After France closed the border to Spain in 1937, however, volunteers could reach Spain only by climbing the Pyrenees Mountains at night.

In Spain, the African American volunteers found life sharply different from what they had left in the United States. When the Lincolns marched, recalled Marion Noble, a white Detroit volunteer, “Spanish women showered the Black men with smiles and flowers.” “I never felt more like a man than in Spain,” reported Luchelle McDaniels. Years later Tom Page told James Yates:

“I remember how sometimes a whole town would turn out when they heard there was a Black man around. Spain was the firstplace that I ever felt like a free man. If someone didn’t like you, they told you to your face. It had nothing to do with the color of your skin.”

Recruits from the United States were assigned to the English-speaking Fifteenth Brigade that also included British, Canadian, and Irish units, and Spanish-speaking Latin Americans. Linking Spain’s struggle to their own history, U.S. volunteers called their units the Lincoln and Washington battalions and named the artillery and machine-gun companies after abolitionist Frederick Douglass and anti-slavery martyr John Brown.

From infantry privates to officers, the Lincoln Brigade was the first fully integrated U.S. army. Moreover, Communists in leadership positions, such as Steve Nelson, resolved that African Americans would have an opportunity to prove their capacities and leadership abilities. College student Oscar Hunter became the Political Commissar of Hospitals. “How long do you think it might take me to get up to such a position in the United States?” he asked a Black U.S. journalist who answered “not in the next one hundred years.” “I can rise according to my worth, not my color,” noted Oliver Law.

In the unit’s first battle at Pingarr Hill in the Jarama Valley the fledgling Lincoln Brigade faced a baptism of fire without air cover or artillery support. Here Alonzo Watson was the first African American killed in Spain. But 23-year old machine-gunner Walter Garland was twice wounded, commended for bravery and was promoted to lieutenant together with Oliver Law.

Other African Americans also demonstrated raw courage and unusual battlefield skills. Fellow soldiers described Doug Roach as a man with “infectious enthusiasm” who “could carry a heavy machine gun over the hills of Brunete when others were too exhausted to walk.” Luchelle McDaniels, or “El Fantastico,” could hurl grenades long distances with either hand. Lt. Walter Garland trained Milton Wolff, the last Lincoln Brigade commander, who recalled:

“Whatever I learned about the Maxim machine gun he taught me. But more important . . . he instilled in me the conviction that we could go out there and take on the whole bloody professional fascist armies and kick the shit out of ’em.”

Spain had a strong impact on African American volunteers. Salaria Kea discovered “divisions of race, creed and nationality lost significance when they met a united effort to make Spain the tomb of Fascism… I saw my fate, the fate of the Negro race, was inseparably tied up with their fate…” Of the many tragedies she “shared with the Spanish people,” Salaria Kea remembered most vividly the fascist bombings of children’s colonies near Barcelona and an attack on her field hospital:

“I heard screams coming from every direction. I saw people I had never seen before; many moving dirt and shovels, others were using their hands. Some were running with pieces of bodies in their arms. I was in shock. . . . Many of the patients had been killed. Newly wounded patients were being brought in. We began to work on them. Soon we ran out of sterile supplies.”

In March 1938 a hospital bombing left Kea buried for hours. “I was dug out from under six feet of rocks, shells and earth. The resulting [back] injury left me unfit for further hospital service. I was furloughed home.” In the U.S. Kea “traveled through the country to secure medical supplies and food so desperately needed by the people in Spain. This I did until Spain fell to Franco.”

Other African Americans were deeply moved by their experiences. Pat Battle, a quiet medical student at Howard University, told James Yates about the fascist destruction he had seen in Madrid of schools, libraries and educational institutions. He concluded: “The fascists tear down that which it has taken people years to build.”

Oliver Law stood out in Spain for his soldierly background and military bearing. Early in 1937 (the year General Colin Powell was born) Law’s prowess earned him many battlefield promotions. After he was put in charge of his machine-gun company, Lincoln Brigade commander Marty Hourihan recommended Law for officers’ school, and he was headed for leadership.

When the position of Lincoln Brigade Commander became available, Captain Law was chosen. Steve Nelson, who had worked with Law in Chicago and served on the committee of three that picked him, stated “he had the most experience and was best suited for the job.” He was, Nelson emphasized, “the most acquainted with military procedures on the staff at the moment … he was well liked by his men … When soldiers were asked who might become an officer — ours was a very democratic army — his name always came up. It was spoken of him that he was calm under fire, dignified, respectful of his men and always given to thoughtful consideration of initiatives and military missions.”

Law’s friends in the Brigade included his two white runners, Jerry Weinberg, and Harry Fisher, both from New York City. Fisher has provided vivid recollections of Law as Brigade commander. As Law led his men at Brunete in July 1937, Fisher has written, “What I remember is the great joy on Oliver Law’s face as he saw the fascists running. After a while, with the men exhausted and far in front of the tanks, Law feared that we would fall into a trap, and ordered the men to slow down.”

Subsequently, Law took command of the Brunete offensive and was killed while leading an attack against the fascist lines on “Mosquito Ridge.”

Meanwhile on the U.S. home front the African American community gave full support to the Lincoln brigade’s anti-fascist commitment. Wartime opinion polls found that two-thirds of the American public supported the Republic, although most citizens also feared that direct U.S. intervention would endanger world peace. Committees to Support Spanish Democracy formed in Harlem, and national figures such as Lena Horne, W.C. Handy, and Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. played prominent roles in fund-raising efforts.

Famous African Americans toured the war zone. Langston Hughes’ dispatches from the trenches, his revolutionary poetry, and his speeches reflected a growing commitment to what he and others saw as the determination of the world’s common people to achieve liberation, self-determination and democracy. In Spain Langston Hughes cultivated a friendship with the poet Edwin Rolfe, editor of the Volunteer for Liberty. At a meeting in London to raise funds for the Spanish republic, actor and singer Paul Robeson announced his support of the cause in Spain. An artist, he said, “must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery.” Robeson and his wife Eslanda subsequently visited Spain and toured the front to sing for the antifascist troops.

Despite the efforts of the Spanish people and of the International volunteers, the Republic fell to Franco’s forces in March 1939. As Ernest Hemingway began to work on his epic about Spain, For Whom The Bell Tolls, he paused to write an elegy for the American dead.

After Spain

African American veterans returned from Spain arm in arm with their white comrades. Photographs of the time show men who had fought together in battle standing together again aboard the ships that brought them home.

As the Lincolns disembarked in New York, well-wishers greeted them with kisses, hugs and shouts. But they landed in a homeland that did not honor their courage against fascism and racism. FBI agents who James Yates thought “would have been more comfortable with the fascists we had been fighting in Spain,” detained the veterans and took their passports. Then New York City reality set in. After registering Yates’ white comrades, a clerk at the Grand Hotel on Broadway told him “No vacancy.” “The pain went as deeply as a bullet could have done. I had the dizzy feeling I was back in the trenches again. But this was another front. I was home.” Yates and his comrades left for a more hospitable hotel.

Though Black veterans had returned to what Yates called “another kind of warfare,” like the others, he said, “I had grown tougher.” During World War II Yates served in a segregated U.S. Army Signal Corp unit, but because of his service in Spain, he was pulled out when his unit was shipped overseas. Veterans such as Crawford Morgan and Joe Taylor battled Jim Crow rules in the Army that assigned African Americans to what Taylor called “nasty jobs.”

During the war Rev. Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. proposed that at least one U.S. Army unit be modeled on the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. But this did not come to pass and for Black veterans of Spain a segregated army meant new battles. In 1942 sailor Luchell McDaniels in Durban, South Africa, led fellow sailors in a sit-down protest at Woolworth’s segregated lunch counter, then integrated a movie theater, and finally led a sailors’ march through Durban streets demanding treatment as “human beings.” He returned to carry his anti-racist message to white audiences in his home state of Mississippi.

During World War II Walter Garland lectured to white officers about the battle of Brunete and also helped invent an improved machine-gun site. But when a white MP used the phrase “black bastard” Garland fought back and was arrested. As chief instructor of a segregated quartermaster unit Vaughn Love introduced political lectures designed to stir the pride of Black soldiers, but when his unit went overseas he faced continued racist treatment that led to violent confrontations with white soldiers.

Salaria Kea enlisted in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps and this time her experience was highly valued by superiors. Jerry Weinberg, who had tried to rescue Oliver Law at Brunete, won a Distinguished Flying Cross for bombing raids over enemy Romania, was once shot down but escaped from a Turkish prison to Egypt and died over Germany.

In 1945 Sergeant Edward Carter, Jr. was decorated for his extraordinary courage when he single-handedly fought off a German squad and returned with two prisoners despite eight shrapnel and bullet wounds. But Carter’s outspoken views on the mistreatment of African American soldiers in the U.S. army and his appearance at a rally sponsored by a group that had attracted the attention of the FBI, sealed his future. In 1949 he was denied the right to re-enlist in the Army, not given an explanation or a hearing, and placed under Army surveillance until his death in 1963. His service in the Lincoln Brigade was among the principal reasons his status changed from decorated hero to pariah.

Carter and his family never ceased their campaign to clear his name. In 1997 President Bill Clinton posthumously awarded Carter the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroism in Germany half a century before. Two years later President Clinton publicly apologized to his family for the way Army Intelligence scapegoated a patriot and national hero.

After Spain many Lincoln veterans, white and black, returned to fight for human rights in the United States. Many became supporters of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. or the Black Power movement. Luchelle McDaniels led a protest march in Sacramento, California, to demand sidewalks in Black neighborhoods.

James Yates and other Lincoln veterans also faced persecution during the McCarthy era. Yates reported, “I was harassed by the FBI and rejected for every job for which I applied.” He finally had to set up his own TV repair shop. The FBI accumulated extensive files on many veterans including Walter Garland. Crawford Morgan and others were questioned by Congressional committees about their service in Spain and their struggle against segregation and discrimination. Finally, Ramon Durem used poetry to express his dissent from Cold War culture.

From 1964 to 1968 Yates served as president of the Greenwich Village-Chelsea chapter of the NAACP that sent tons of food and clothing to civil rights activists in his birth state of Mississippi. White veterans pitched in as well. In Pittsburgh in 1949 Steve Nelson lived in a Black neighborhood and with his wife and two children took part in marches that successfully desegregated a swimming pool. In 1964 Abe Osheroff worked with African Americans to rebuild a Community Center in Mississippi. His car was dynamited and he had to carry a .38 pistol and a shotgun. “I had gone abroad, so to speak, to fight in a foreign war,” he said. In 1966 Lincoln nurse Ruth Davidow volunteered to teach medical care procedures for African Americans in Mississippi. Three years later she served the medical needs of Native Americans who occupied Alcatraz, and often was the only white person the occupiers allowed on the island.

Vaughn Love saw the “fighters for South African freedom” as part of his “battle against racism and fascism.” The Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade became one of the first organizations to send medical aid to the African National Congress, to demand Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, and to support a South Africa free of racial oppression.

African Americans who fought against fascism in Spain and in World War II did not automatically embrace the civil rights leadership’s policy of nonviolence. Their experience led them to think that entrenched bigotry would not bow to nonviolence preached by religious leaders. Vaughn Love stayed away from nonviolent protests “because I would probably have gotten into trouble . . . I would not have turned the other cheek.”

The rise of the “Black Power” movement attracted Black veterans such as Harry Haywood who saw it vindicating his earlier revolutionary writing. He talked about the African American masses “taking political power into their own hands.” But more agreed with Vaughn Love who said, “You must try to get into the mainstream of America, for this is where we belong. Where is the black power when you don’t have a job” He urged others to “work within the system and with people who are going in your direction.”

The African Americans of the Lincoln Brigade never ceased their fight against fascism. They carried it into World War II and then into the long struggle for human rights back home and in the world.

Curriculum Materials

There are two curriculum guides for African Americans in the Lincoln Brigade lesson. The first plan includes an assignment where students will write two articles (news article, letter to the editor, editorial commentary, or comic) for their group’s newspaper. The second plan culminates in the production of an illustrated slide show presentation or web page.