Geronimo: The True Story Of The Feared Apache Warrior (original) (raw)

Fending off both the U.S. and Mexican armies on the American frontier, Geronimo led the Bedonkohe band of the Apache Native Americans before being captured and turned into a sideshow.

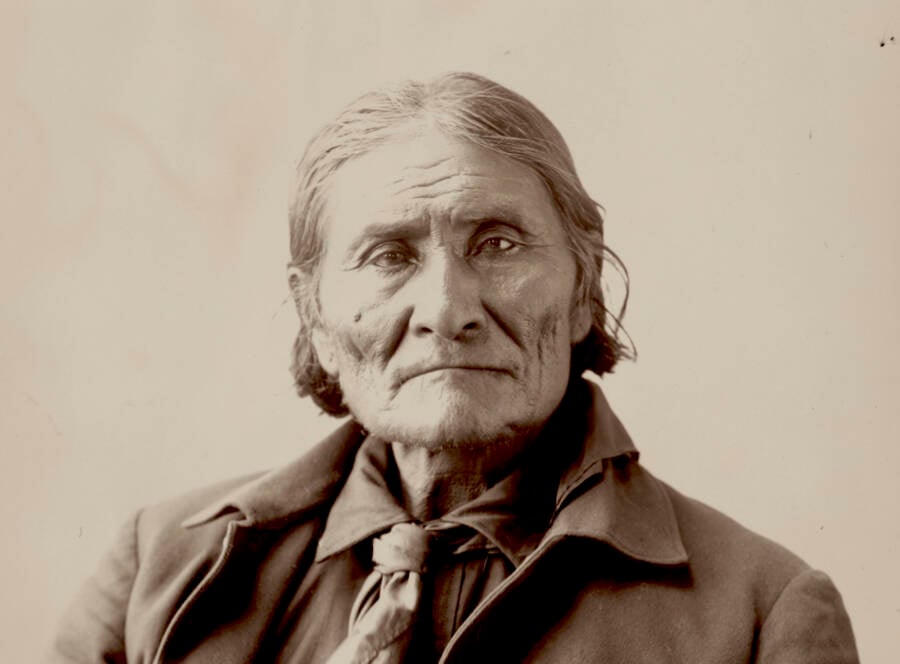

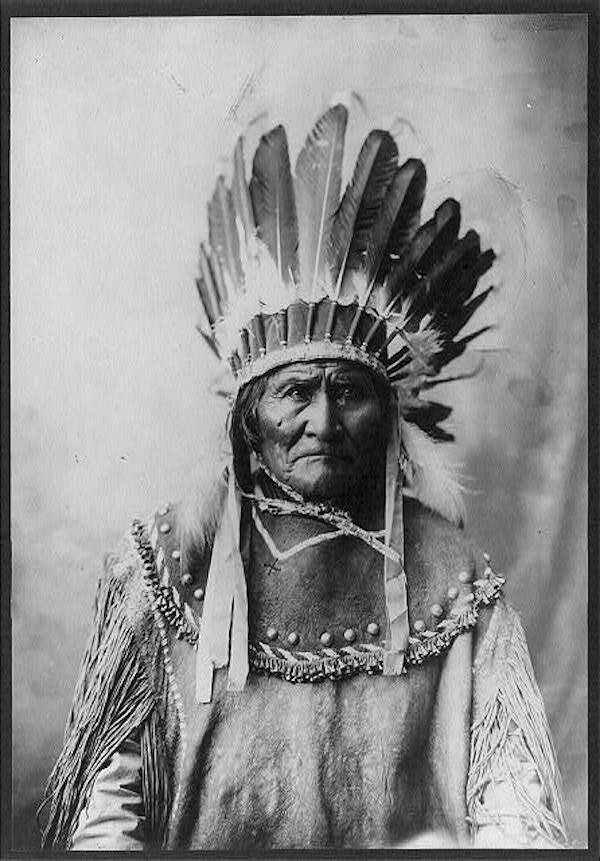

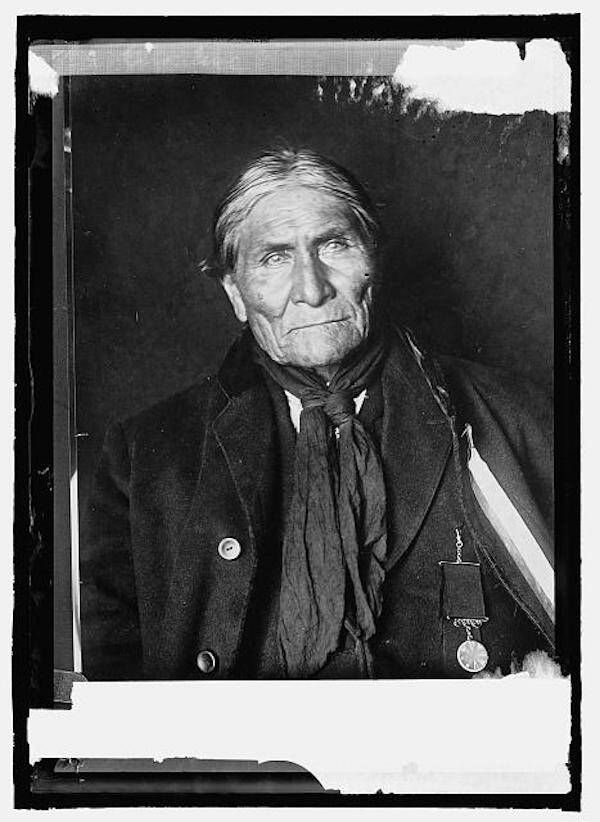

Library of CongressTo this day, the Apache military leader and medicine man Geronimo remains historic for his fearless stand against U.S. and Mexican forces in the 19th-century American West.

“Although I am old, I like to work and help my people as much as I am able.” Geronimo, the legendary Apache warrior, wrote these words near the end of his life, after 75 years of doing just that: helping his people.

Between 1851, when Mexican troops massacred his family, and 1886, when he was captured by the American forces that had been hunting him for years, Geronimo fought for his people time and time again. Beset by colonial powers on all sides, this fearless warrior and medicine man led the Apache through a period of brutal subjugation as they went from free-roaming southwestern tribespeople to prisoners of war.

For decades, Geronimo helped stave off a complete surrender of his people — until the Apache was overwhelmed, he was forced to surrender, and then turned into a sideshow exhibit by the American government.

This is the story of Geronimo and his heroic fight for freedom and dignity.

The Mythic Origins Of Geronimo Before He Led The Apache

Geronimo — whose given name was Goyaałé or Goyathlay, meaning “the one who yawns” — was born in No-Doyohn Canyon in June 1829. The canyon was then part of Mexico but is now near where Arizona and New Mexico meet.

Wikimedia CommonsGeronimo publicly said he no longer considered himself a Native American, and that white people were his brothers and sisters. How genuine this was remains unclear.

Before the Bedonkohe leader led the Apaches to defend their homeland against the encroaching United States, Geronimo was a mere child born into the harsh realities of the 19th century. The fourth of eight children, he helped his parents work their two acres of land, planting beans, corn, melons, and pumpkins.

Since the man himself has transcended the confinements of fact, his origin story bends toward myth. According to legend, after he hunted and killed his first animal, he swallowed its heart raw for good luck.

But his good fortune was spotty. His father died early on, and Geronimo’s mother chose to remain unmarried and live with her son.

In 1846, when he was 17, Geronimo became a warrior. “This would be glorious,” he later wrote in his autobiography. “I hoped soon to serve my people in battle. I had long desired to fight with our warriors.”

Another plus was that he was now able to marry Alope, his longtime lover. Immediately after he was granted warrior privileges, Geronimo went to Alope’s father and asked if she could be his wife. Her father granted the marriage, as long as Geronimo gave him “many” ponies.

Geronimo “made no reply, but in a few days appeared before his wigwam with the herd of ponies and took with me Alope. This was all the marriage ceremony necessary in our tribe.” They went on to have three children.

Wikimedia CommonsGeronimo was a naturally gifted hunter. It is said that he ate the heart of his first kill in a symbolic gesture to protect himself from those who might hunt him.

But threats to their survival constantly loomed.

The Bedonkohe, which were part of the Chiricahua band of the Apache, could rely on nobody but themselves, and frequently raided nearby indigenous and Mexican villages. The government, of course, was not amused by this group of marauders disturbing the peace; in the mid-1840s, the government of Chihuahua, Mexico put out an official bounty on Apache scalps.

If you captured and killed an Apache warrior, you’d get $200 — equivalent to several thousands of today’s dollars.

Mexican Forces Kill Geronimo’s Family — And He Seeks Vengeance

In the summer of 1858, Geronimo changed. The mild-mannered, peaceful man turned into a warrior hellbent on revenge.

It all happened when his tribe journeyed to a Mexican town called Kaskiyeh. While the men would go into town during the day to trade with the locals, the women and children would stay at the camp while a few men stood guard.

But one day when the traders returned, everyone — including Geronimo’s wife, mother, and children — had been brutally murdered. Villagers told them that Mexican troops from a nearby town had done the killing.

Wikimedia CommonsFrom left to right: Geronimo, Yanozha (his brother-in-law), Chappo (his son by his second wife), and Fun (Yanozha’s half brother). 1886.

Seeing his entire family slain in cold blood left Geronimo with a hatred of Mexicans that he never overcame.

“I was never again contented in our quiet home,” he wrote. “I had vowed vengeance upon the Mexican troopers who had wronged me, and whenever I…saw anything to remind me of former happy days my heart would ache for revenge upon Mexico.”

The death of his family and subsequent lust for retribution set Geronimo on a path of battle and bloodshed. And a visit by a disembodied voice fueled his fire.

Geronimo, The Fearless Warrior

The Apache leader was in deep mourning when he heard a voice assuaging his concerns about the dangers of retribution. By his own account, he was comforted and told the enemy’s weapons wouldn’t touch him — that he’d be safe, should he seek out revenge.

“No gun can ever kill you,” the voice told him. “I will take the bullets from the guns of the Mexicans, so they will have nothing but powder. And I will guide your arrows.”

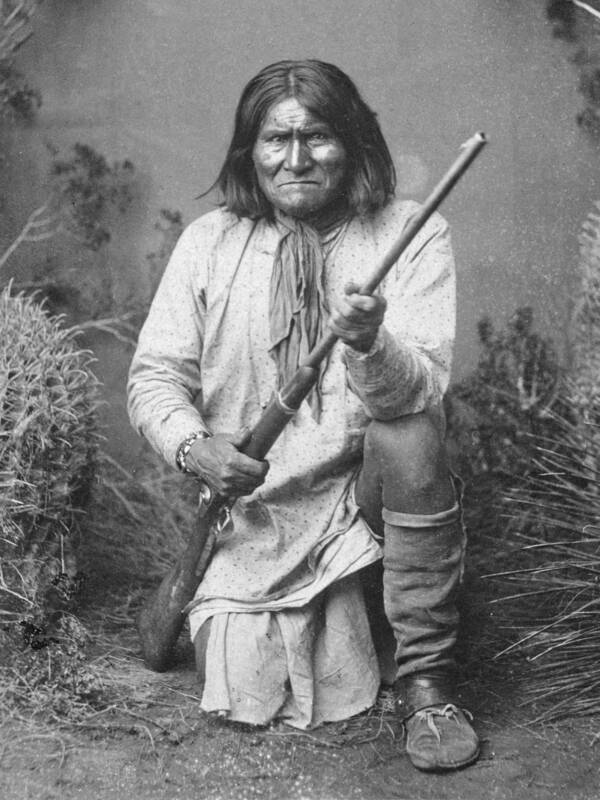

Library of CongressGeronimo vowed to seek revenge on Mexicans after a group of soldiers killed his wife, mother, and children during a raid.

And sure enough, the Apache found himself virtually unharmed in his next skirmish with Mexican soldiers.

Accounts of him in battle lauded his bravery and fierce fighting style. He didn’t know how to fire a gun, and so he ran toward his enemy in a zig-zag pattern, avoiding their bullets, until he got close enough to stab them with his knife.

He frightened his Mexican enemies so much that they began yelling “Geronimo.” Some believe they were screaming the Spanish word for Jerome — and that they were pleading for help from St. Jerome to escape Geronimo’s fury.

The monicker stuck — as did the man’s renewed passion for warring without abandon. This combination of anger, fearlessness, and skill made Geronimo one of the most esteemed fighters of the Apache — one the Americans would soon come to know as well.

The Apache War Against Mexican And American Troops

The California Gold Rush brought an intense influx of Americans to the west. From the late 1840s to the 1860s, hundreds of thousands migrated to California and neighboring regions to try their luck mining gold, silver, and copper. Many settled in New Mexico — on Apache lands, including those of Geronimo and his fellow Apache leader Cochise.

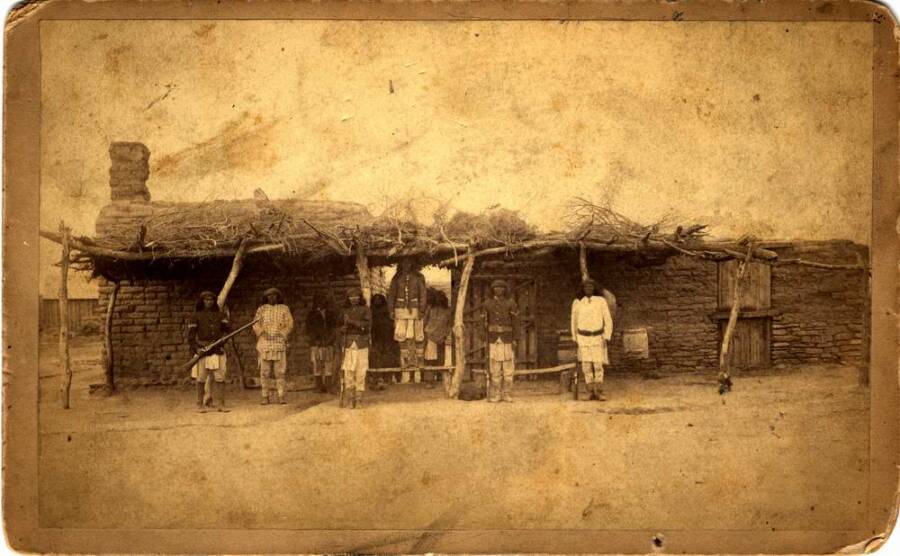

Wikimedia CommonsThe guard house at the San Carlos Reservation in 1880.

When war between settlers and the native populations reached a fever pitch, the U.S. Army imposed laws to protect the newly arrived. The federal government declared that all Native Americans living in Arizona and southwest New Mexico must be relocated to Arizona’s San Carlos Reservation in the 1870s. The reservation, known as “Hell’s 40 Acres,” was arid and treeless. It was an Apache prison.

Geronimo was a free man, even when the American government told him he was barely the latter. He didn’t follow their orders, nor did he respect their imposition on his autonomy. And so he and Juh, another Apache leader, took two-thirds of the Chiricahua with them to the Ojo Caliente Reservation in New Mexico instead of marching into San Carlos as instructed.

But again, Geronimo’s luck soon ran out. His Apache scouts betrayed him, telling him that a visit by John Clum, an American agent at San Carlos, was a mere peace meeting. Instead, Clum captured Geronimo and his people and took them to San Carlos, where they were put in shackles. Clum hoped the U.S. government would put them to death.

Library of CongressGeronimo at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York in 1901.

In a dark parallel to Columbus’ conquest of America, many prisoners in San Carlos were exposed to diseases like smallpox. While they were certainly fed, inmates subsisted on starvation rations. Conditions were so bleak that it didn’t take long for Geronimo to orchestrate an escape.

In 1878, he and his friends fled into the mountains.

The Surrender And Imprisonment Of Geronimo

Outraged at the wit and gall of Geronimo and his escape, U.S. Brig. Gen. Nelson A. Miles grabbed 5,000 soldiers — a quarter of the Army — and hunted the escapee and his 17 Apache brethren through the Rocky and Sierra Madre Mountains.

When inevitable surrender (or death) loomed, Geronimo displayed a sense of character that has long since defined his legacy. After being chased for hundreds of miles, the military caught up with the Apache band, and Geronimo offered to turn himself in — if they allowed his men to stay together.

“I will quit the warpath and live at peace hereafter,” he said.

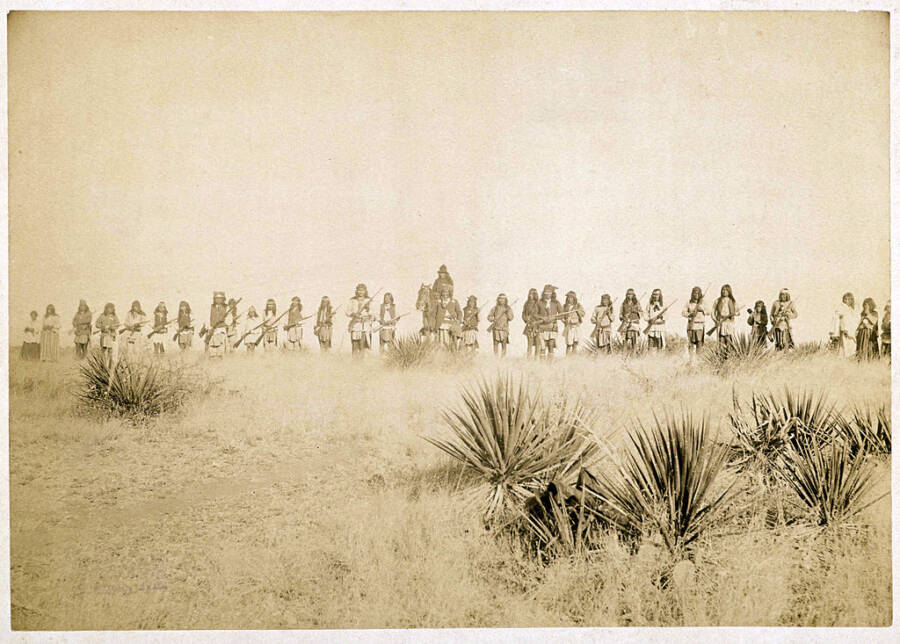

Wikimedia CommonsThe last photograph of Geronimo and his Apache as free men. C.S. Fly took this photo right before they surrendered to Gen. Crook in the Sierra Madre Mountains. March 27, 1886.

He kept his word, as the rest of his life was comprised of non-violent captivity which produced no further bloodshed on his part — just shameless exploitation. Before that, unfortunately, more loss and tragedy had to befall his loved ones.

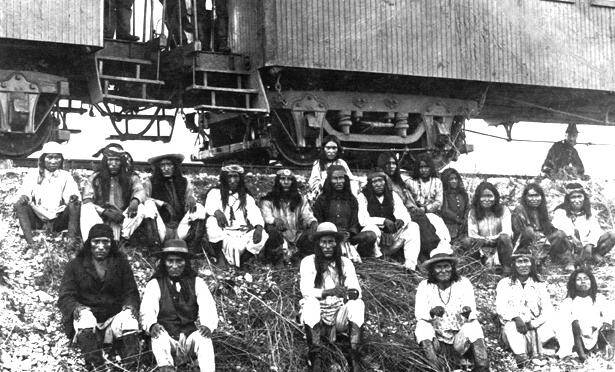

Twenty-seven Apaches were stuffed into train cars on Sept. 8, 1886, and taken to Pensacola, Florida. Geronimo was condemned to saw logs. Many of them died of tuberculosis on the way. The next year, the malnourished captives were transported to the Mount Vernon Barracks in Alabama.

It was here that Geronimo — unhealthy, underfed, spiritually challenged — made the inconceivably difficult decision of letting his new, pregnant wife Ih-tedda and their daughter Lenna leave for New Mexico. In Apache culture, this was the equivalent of getting a divorce. It was the last time he ever saw them.

In 1894, Geronimo and 341 other Chiricahua prisoners of war were transported to an American military base in Fort Sill, Oklahoma. He was eager to move; he envisioned his people would all have a “farm, cattle, and cool water” at their disposal there.

“I do not consider that I am an Indian anymore,” he told the American soldiers. “I am a white man and [would] like to go around and see different places. I consider that all white men are my brothers and that all white women are my sisters — that is what I want to say.”

But the government wouldn’t let them assimilate. Instead, the Apache remained political prisoners. The government gave them each cattle, hogs, chickens, and turkeys, but they didn’t know what to do with the hogs, so they didn’t keep them. When they sold their cattle and crops, the government would keep some of the money they earned and put it into an “Apache Fund,” from which the Apaches apparently didn’t reap any benefits.

“If there is an Apache Fund,” Geronimo wrote, “it should some day be turned over to the Indians, or at least they should have an account of it, for it is their earnings.”

Wikimedia CommonsGeronimo (third from the right) and his Apache, during a stop on the Southern Pacific Railway near Nueces River, Texas. 1886.

Journalists visited the permanently detained Apache, and, fascinated by his legend, frequently asked if they could see the blanket he had made from 100 scalps of his victims. He disappointed all of those who inquired, as that story was merely propaganda to skew the public discourse against Native Americans. All he wanted, and asked for, was to let his Apache brothers and sisters return to the Southwest.

“We are vanishing from the earth,” he said. “The Apaches and their homes each [were] created for the other by Usen [the Apache life-giver] himself. When they are taken away from these homes they sicken and die. How long will it be until it is said, there are no Apaches?”

American Exploitation Of Indigenous People

Geronimo quickly became a celebrity of the Apache Wars, as Anglo-Americans saw Natives like him as nothing more than a savage or a shackled ape — something to make money off of. His involuntary career as an item on display began in 1898 when he made an appearance at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exhibition in Omaha, Nebraska. In 1904, he appeared at the World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri.

He apparently had no qualms about securing a portion of that lucrative celebrity pie for himself — even if the fairs advertised him as “The Worst Indian That Ever Lived.” It was, after all, him that people were paying to see.

“I sold my photographs for twenty-five cents, and was allowed to keep ten cents of this for myself,” he wrote. “I also wrote my name for ten, fifteen, or twenty-five cents, as the case might be, and kept all of that money. I often made as much as two dollars a day, and when I returned I had plenty of money — more than I had ever owned before.”

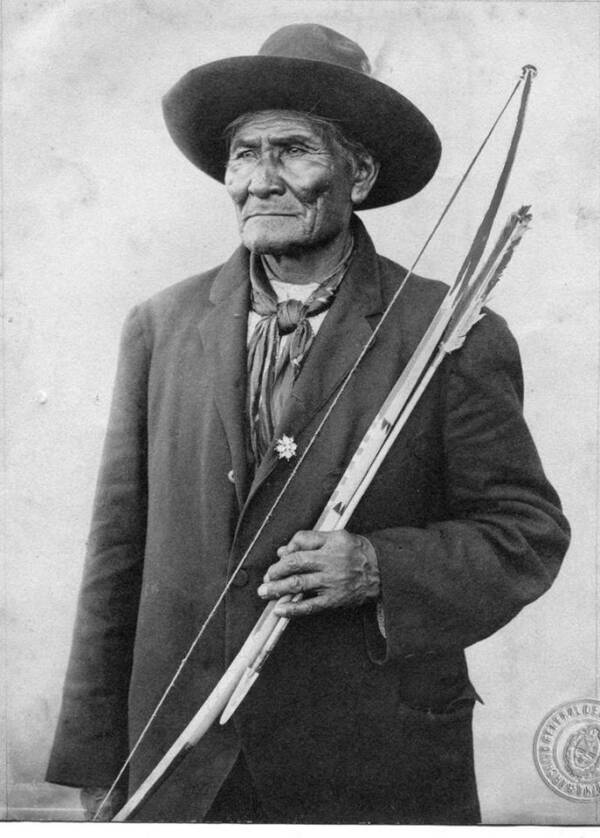

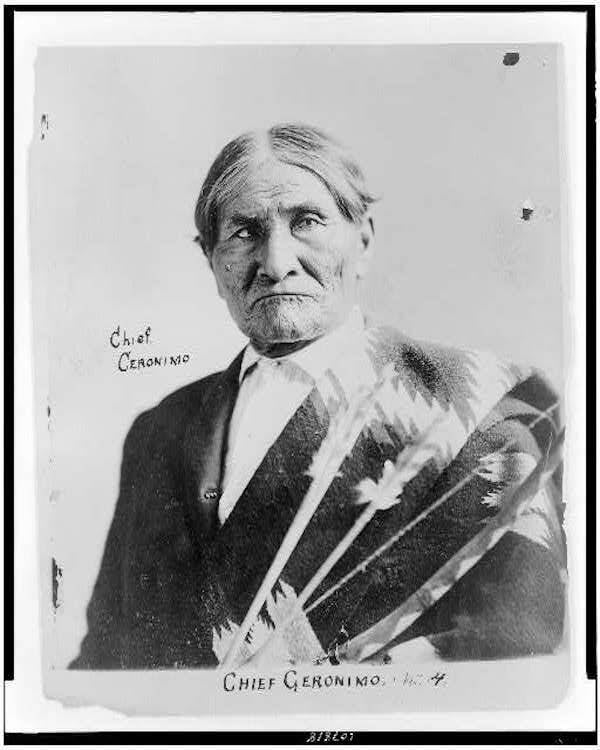

Library of CongressGeronimo made money by selling signed photographs like this. But despite what the photo says, he was never a chief.

Regardless of Geronimo’s new disposition — or perhaps, partly because of it — his business savvy was appreciated even after he died. Bruce Shakelford, who appraised Geronimo’s belongings when he passed, was stunned at Geronimo’s foresight in terms of branding and customer appeal.

“I’ve seen his signature on little drums, on signed cabinet card photographs of himself,” he said. “I mean, this guy was early marketing personified. This guy was a celebrity. And he was the main celebrity. He had killed white folks and staked them over ant beds. He was a bad guy… He sold artifacts, and they didn’t necessarily have anything to do with the Apache. People would bring him things he could sell, and they knew they could get more money for it with his signature, so they made a deal.”

The Last Days Of Geronimo And The Legacy That Endures

Geronimo hoped to convince President Theodore Roosevelt to let him and the Apaches return home to the Southwest. He had even converted to the Dutch Reformed Church — Roosevelt’s church — in 1903 to get on his good side. And though he did attend the president’s second inauguration in 1905, and met with the president afterward, he was denied the request.

Through an interpreter, Roosevelt told Geronimo that he had a “bad heart.” “You killed many of my people; you burned villages,” he said. “[You] were not good Indians.”

Library of CongressGeronimo pleaded with President Roosevelt to let the remaining Apache return home to the southwest. His request was denied.

Still, Geronimo dedicated his autobiography to Roosevelt, hoping he’d read it and come to understand the Apache side of the decades-long conflict.

“I want to go back to my old home before I die,” Geronimo told a reporter in 1908. “Tired of fight and want to rest. Want to go back to the mountains again. I asked the Great White Father [President Roosevelt] to allow me to go back, but he said no.”

By this point, Geronimo had yet another wife (the Apache were polygamous), Zi-yeh. Dissuaded by Roosevelt’s rejection of returning home, Geronimo spent the time gambling, partaking in shooting contests, and betting on horse races. Zi-yeh died of tuberculosis, leading Geronimo to take care of the household.

He washed dishes and swept the floor, cleaned the house, and took care of his extended family. Geronimo was reportedly so visibly devoted to his daughter Eva, who was born in 1889, that one visitor remarked, “Nobody could be kinder to a child than he was to her.”

Library of CongressGeronimo pictured at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904.

It was around 1908 that Geronimo’s age began to notably affect his day-to-day life. He grew weaker and his mind began to wander. He started forgetting things. His road to the great beyond began on Feb. 11, 1909, when he sold some bows and arrows in Lawton, Oklahoma.

Geronimo spent his earnings on whiskey. That night, he rode drunk and accidentally fell off his horse and landed in a creek. Only the following morning was he discovered. He was alive and well, except for the pneumonia that had already begun to set in.

His final wishes were that his children be sent to Fort Sill so they could be beside him when he transitioned. It’s unclear who exactly got these directions wrong, but that request was sent via letter, rather than a telegram. Geronimo died on Feb. 17, 1909, before his kids arrived. He was 79 years old.

What remains of one of history’s most incredible Native American warriors today is an inspiring albeit tragic story of a man who stood up for himself and his people against great odds. Geronimo protected his community whenever he could, and did everything for his family. Despite his best efforts, he was robbed of those he loved, and treated like an animal once everything was lost.

To this day, countless people visit the gravestone of Geronimo, adorned with a soaring eagle, and imagine the courage it must have taken to defy the burgeoning American empire as it was roaring into power.

After reading this biography of Geronimo, learn the story of Squanto. Then, explore the American frontier in 48 historic photos and check out these stunning Native American masks of the early 20th century.

History Uncovered Podcast Episode 52: The Most Astonishing Native American Warriors To Ever Live From iconic figures like Geronimo to lesser-known leaders like Red Cloud, meet the most astonishing Native American warriors in history.

History Uncovered Podcast Episode 52: The Most Astonishing Native American Warriors To Ever Live From iconic figures like Geronimo to lesser-known leaders like Red Cloud, meet the most astonishing Native American warriors in history.