Ishi, The Last Native American, Reminds The World Of What It Lost (original) (raw)

Published February 10, 2013

Updated February 1, 2024

Ishi emerged from the forests of California in 1911, nearly 40 years after the world thought his people had disappeared from the earth.

On Aug. 29, 1911, Ishi, the last of the Yahi, walked out of the California wilderness and into American culture.

On Aug. 29, 1911, Ishi, the last of the Yahi, walked out of the California wilderness and into American culture.

He emerged onto a scene that had mostly forgotten the Native Americans who once roamed the land. Thin from starvation and soot-smudged from the fires that had ravaged the nearby forest, he was a shocking sight to the inhabitants of Oroville.

They called him a “wild man” and took him into custody — not for foraging on private property, but because they hoped to protect him. At sea in a strange modern world, he seemed to them a danger to himself.

But there was not much left for Ishi to lose. The worst had already happened long ago — and it happened because of towns like Oroville.

The Price Of The California Gold Rush

Wikimedia CommonsA wooden gold sluice during the California Gold Rush.

On Jan. 24, 1848, James W. Marshall found gold in the water wheel at Sutter’s Mill, giving rise to the largest mass migration in modern history.

The gold rush brought approximately 300,000 people to the wilderness of California.

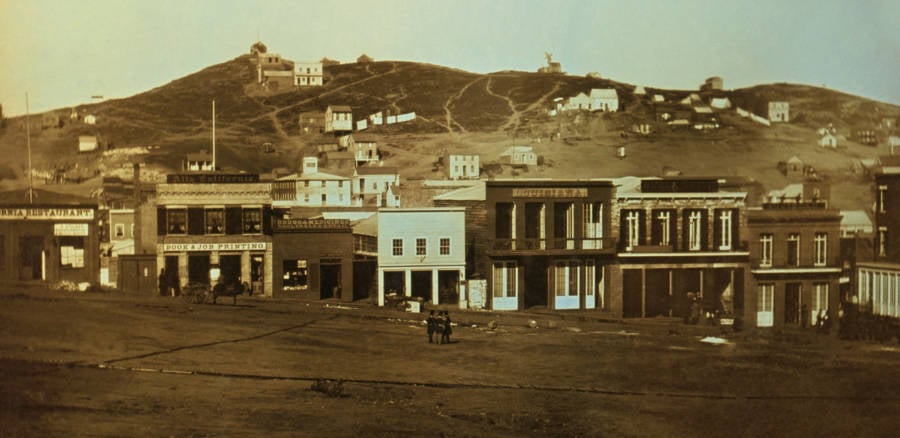

The population of San Francisco, a fledgling township in 1948, grew from 1,000 to 25,000 in two years. The supply ships that carried the growing city’s goods unloaded and sat abandoned in the harbor; their crews had fled to search the California hills for ore.

Wikimedia CommonsSan Francisco harbor, 1851.

But by 1850, the easy gold was gone, and miners had to search farther and farther afield. As they dug deep into remote countryside, they encountered Native Americans. Their activity began to disturb traditional Native American fishing and hunting grounds, scattering game and polluting water supplies.

Library of Congress via Wikimedia CommonsThe rapidly growing town of San Francisco in 1851.

The deer vanished, and the fish died. The newcomers brought diseases, like smallpox and measles, that were unfamiliar to Native American immune systems.

Sick, depleted, and starving, some tribes fought back. But they had few defenses against the settler’s guns. Attacks provoked counterattacks that decimated villages.

Relations grew worse, and new towns incentivized violent solutions: they set bounties on the natives, offering 50 cents for a scalp and five dollars for a head.

The rivers of California ran red with native blood.

Ishi Wasn’t His Name

Berkeley

Ishi was not the real name of the man who emerged from the woods of Oroville in 1911, but it was all he could offer the modern world.

Yahi custom dictates that introductions must always be performed by a third party; one may not speak his own name until another person has done so first.

All the people who might once have introduced Ishi were dead. So when asked his name, he said, “I have none, because there were no people to name me.”

He invited them to call him Ishi, which in his native Yahi meant simply “man.” From there, they pieced together the rest of his story.

The Death Of The Yahi

A recording of Ishi speaking, singing, and telling stories is held in the National Recording Registry, and his techniques in stone tool making are widely imitated by modern lithic tool manufactures.

When Ishi was born — sometime between 1860 and 1862 — the Yahi population of 400 was already in decline. The Yahi people had been some of the first affected by the influx of settlers, given their proximity to the mines.

Salmon, a vital part of the Yahi diet, disappeared from the streams. What starvation didn’t finish, Indian hunter Robert Anderson did. Two 1865 raids killed approximately 70 people — much of what remained of Ishi’s kin — and scattered the rest.

It was these raids that a young Ishi survived with his family. Separated from the rest of their people, the small group did their best to continue Yahi traditions. They built a small village on a cliff overlooking Deer Creek, and they kept to themselves.

It was that or death.

FlickrDeer Creek in California. 2017.

Elsewhere, the remaining 100 or so Yahi were being murdered systematically. An unknown number died on Aug. 6, 1866, in a dawn raid conducted by neighboring settlers.

Later that year, more Yahis were ambushed and killed in a ravine. Thirty-three more were tracked and killed in 1867, and another 30 were murdered in a cave by cowboys in 1871.

For 40 years, Ishi and his family hid, avoiding the world being built around them. But time took its toll. One by one, the Yahi died.

A scare when surveyors found their village scattered what was left: Ishi, his sister, his mother, and his uncle. Ishi returned home and reunited with his mother, but his uncle and sister were gone. When his mother died shortly after that, he was all alone.

Ishi, The Last “Wild” Native American

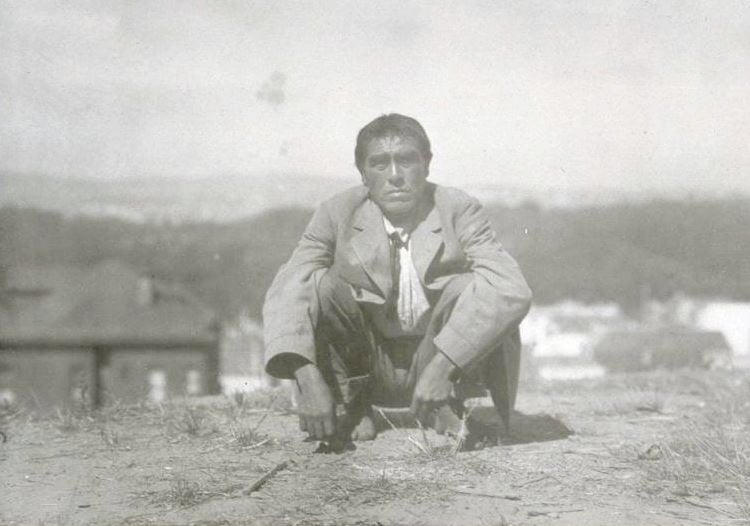

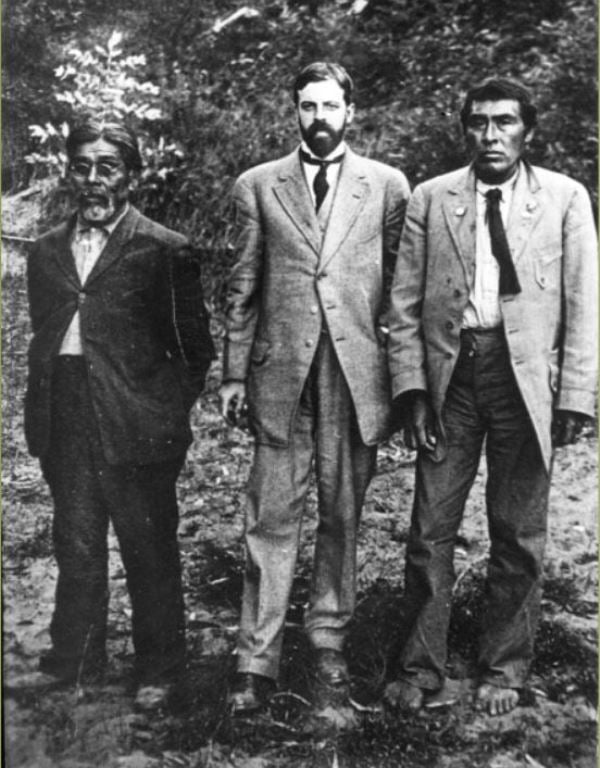

After starvation drove him into the modern world, Ishi’s new home was the Oroville jail. It was there that Alfred L. Kroeber and T. T. Waterman, professors at the University of California, Berkeley, found him.

They took him back to Berkeley, where Ishi in time told them his story. In the last five years of his life, he worked as a research assistant, reconstructing the Yahi culture for posterity, describing family units, naming patterns, and the ceremonies he knew.

It wasn’t a complete picture — Ishi, after all, had been born in his people’s final years, and many traditions had already been lost.

But he did preserve much of his language, and he passed his traditions on to his friends. He taught Saxton Pope, a professor at the medical school, how to make Yahi bows and arrows. They often left the city to hunt together.

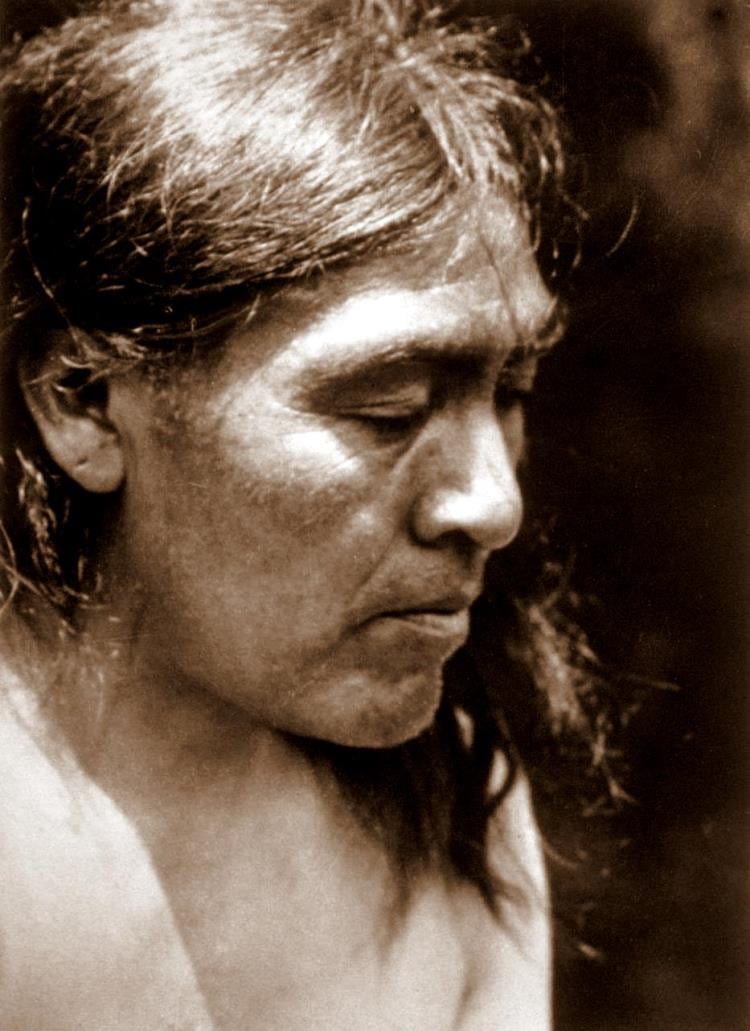

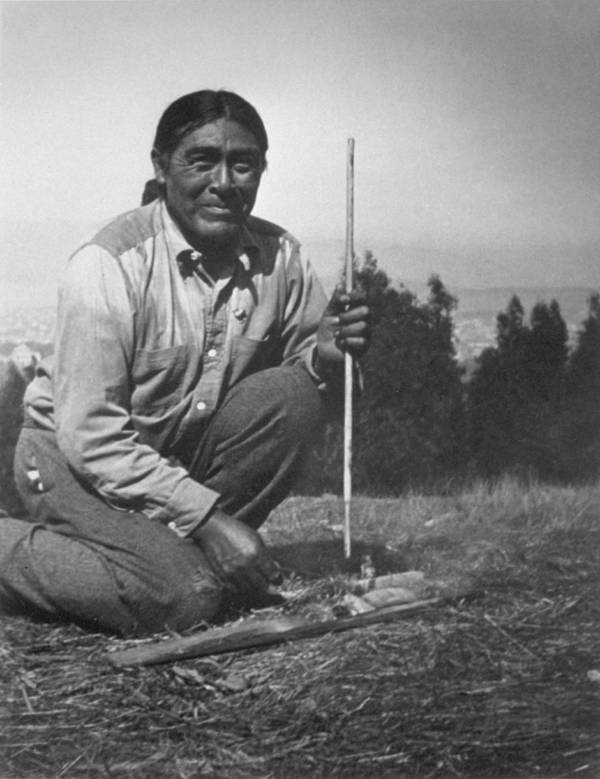

Wikimedia CommonsA photograph of Ishi taken by Saxton T. Pope. 1914.

Sadly, Ishi had no immunity to the diseases of European-American civilization and was often ill. In 1916, he contracted tuberculosis and died not long after.

His friends attempted to give him a traditional burial, but they were too late to prevent an autopsy. They did the best they could to salvage things: his body was cremated as tradition dictated. But his brain was preserved in a deerskin-wrapped Pueblo Indian pottery jar that ended up at the Smithsonian Institution.

A better resolution came about in 2000. New studies began to suggest that while in their decline, the Yahi people had intermarried with tribes that had previously been enemies.

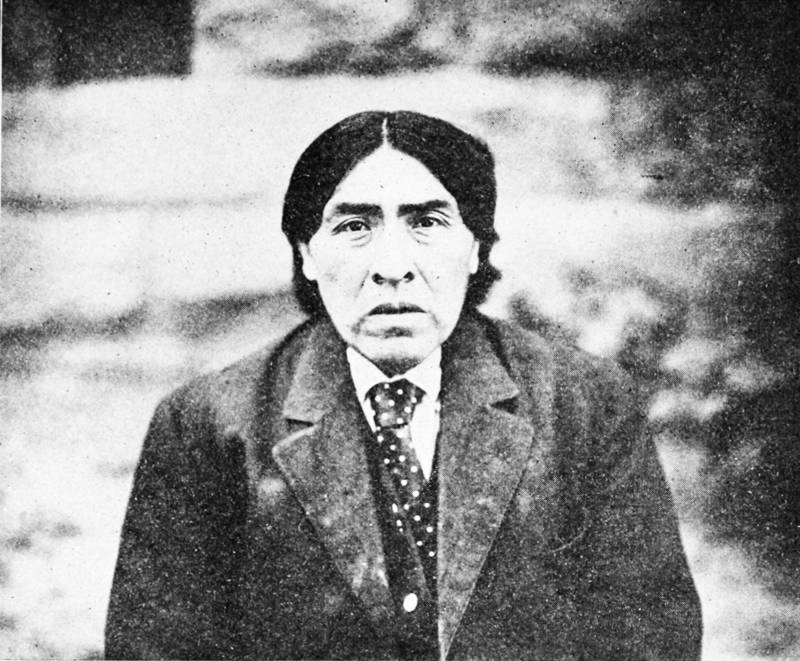

T.T. Waterman/Wikimedia CommonsIshi in 1915.

If true, this meant Ishi’s heritage might still live on in descendants of the Redding Rancheria and the Pit River tribes — something the Smithsonian recognized in 2000 when Ishi’s remains were repatriated there.

In death, Ishi is surrounded by his kin — a thought that gives comfort at the close of a heartbreaking story of loss and isolation.

Did Ishi’s story leave you with questions? Fill in the gaps by reading about the legacy of Native American genocide or view this stunning gallery of Native American masks from the early 20th century.