Housing the future (original) (raw)

This is an article from the Architecture Australia archives and may use outdated formatting

REVIEW LAURA HARDING PHOTOGRAPHY BRETT BOARDMAN, JOHN GOLLINGS

Houses of the Future on the Sydney Opera House forecourt in October 2004. The houses are, from left to right: the Steel House, the Clay House, the Concrete House, the Timber House, the Glass House and the Cardboard House. Photograph John Gollings.

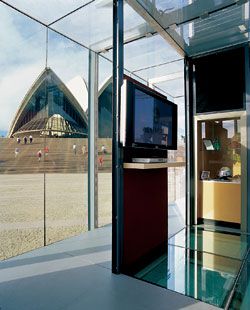

The lure of nanotechnology in the Glass House, by James Muir of the University of Technology, Sydney, in collaboration with Carl Masens, project manager, of the UTS Institute for Nanoscale Technology, and CSIRO, with Arup as sustainability consultant. Sponsored by G. James and Pilkington.

The finely resolved Steel House, by Sarah Bickford and Paul Lucas of Modabode, sponsored by Integrated Steel Solutions, a division of Stramit.

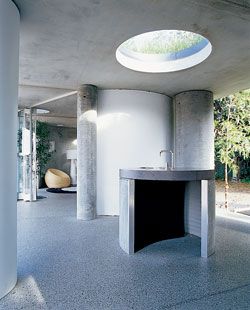

The robust lyricism of the Concrete House, by Peter Poulet and Michael Harvey of the NSW Government Architects Office, sponsored by the Cement and Concrete Association of Australia. Photographs by Brett Boardman.

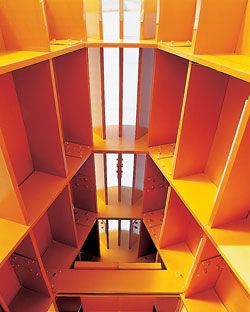

The Timber House, by Stephanie Smith and Ken McBryde of Innovarchi, with technology embedded in the building surface. Sponsored by the Timber Development Association.

The flexible components of the Clay House, by Tone Wheeler of Environa Studios, sponsored by the Clay Brick and Paver Association of Australia.

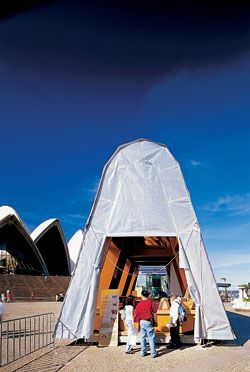

The tent-like Cardboard House, by Peter Stutchbury of Stutchbury and Pape Architects in association with the Ian Buchan Fell Housing Research Centre at the University of Sydney, and sponsored by Visy Specialities.

INVENTIVE AND CONFIDENT speculation about the future characterized the Modern era. Exploiting technological breakthroughs and an emergent consumerist culture, Modernist architects developed case study houses, exhibition pavilions and prototypes that promoted new possibilities for living and captured the public imagination. The optimism and conviction that underpinned this exploration feel strangely distant to us today. In the fleeting and unstable climate of the so-called “digital age” we are preoccupied with the present. The future is confined to the realm of the digital, where it can be explored with impunity – free of the rigours of the “real” and the demands and delight of direct physical engagement.

In this context, participation in the Houses of the Future exhibition must have been an incredibly daunting prospect. Practitioners were asked to experiment ambitiously and physically, constrained by a brief demanding portability and “futuristic” expression and limited by sponsorship arrangements to exploration with a single material. Accordingly, you won’t find a paradigmatic or definitive statement about the Future House among the six pavilions that comprise the exhibition, but rather a series of propositions that, with varying emphasis, examine the role of technology, tectonics, affordability, ecology and typology in contemporary housing.

The tectonic consequences of the convergence of architecture and new technologies is a dominant theme among the six. In rejecting the Modernist use of technology as an insulating mechanism to control, isolate and inure, the proposals wield technology in a manner that offers greater exposure to simple environmental processes, such as the collection and treatment of water and the harnessing of sunlight for energy. The tactile consequences of this shift are invigorating and comprise the most memorable elements of the exhibition.

The Concrete House by Peter Poulet and Michael Harvey exploits a material much maligned by non-architects to form a dwelling characterized by robust lyricism. Precast concrete pipes and tanks are sandwiched between pristine Miesian platforms to enclose circular pockets of space where the arcing movement of sunlight and shadow plays on interior surfaces. A carpet of grasses and sedges whimsically caps the roof plane and treats collected grey water for reuse.

Stutchbury and Pape and Col James’s Cardboard House is similarly evocative. In contrast to Shigeru Ban’s densely columned paper tube structures, this house proposes a cardboard portal structure with interlocking members. Constrained by cardboard’s tensile limitations, the enclosing walls incline to form an intimate tent-like interior with a tiny sleeping loft tucked into its upper bracing members. Wrapped in a protective raincoat, the house is infused with filtered light from above – or generously opened to its surroundings through large pivoting flaps along its northern face.

Distracted by the tantalizing promise of its technology, James Muir and Carl Masens’ Glass House prioritizes the unfettered presentation of prototypical “smart materials” over an investigation of a broader architectural agenda. This leaves the Glass House relying on the invisible atom-scaled processes of nanotechnology for its allure and renders the spatial and tectonic qualities of the house disappointingly prosaic.

More ambitious is the Timber House by Innovarchi. Conceived as a warped timber landscape, this house embeds its technology directly into the building surface. The rationale is that prohibitively expensive technological elements become more economical when they take on multiple functions – generate power, act as cladding/skylights and become an integral part of the architectural language. Unfortunately, the constructional logic of the building failed to match the sophistication of this thinking and the warped surface relied on a painstakingly traditional layering of framing, membranes, battens, insulation and cladding that saw the project remain unfinished at its Sydney debut. The ambitious experimentation of the Timber House stands in stark contrast to Modabode’s Steel House, which is a finely resolved but less challenging exposition of generally accepted environmental and construction principles – a pragmatic and affordable housing option that can be realized now.

The major shortcoming of the exhibition is one mirrored in our existing housing stock – the irresistible appeal of the freestanding dwelling as the predominant housing typology. Declining land and resource availability demand that we address the failures of our existing housing types and learn how to live in greater proximity. This requires an assessment of the relationship between “public” and “private” spaces both within and between our dwellings. Most of the Future Houses rely on Modernist distinctions of served and servant spaces to structure their functions – concentrating bathing and sleeping in enclosed interior modules and unequivocally opening other spaces and functions in the houses to their surroundings and to each other. The Timber House is more extreme – locating its shared areas in the protected heart of the house and pushing private functions to its exposed edges. Such diagrams rely on an unpopulated buffer of private landscaped area surrounding the dwelling to function adequately – a luxury that will simply not be available to most houses in the future.

The Clay House by Environa Studios astutely explores these issues through the typology of a zero-lot courtyard house. A light-filled “solarium” or indoor/outdoor space defines the heart of the house and is edged by Terracade modules in configurations that accommodate households of varying size and composition. This house offers a flexible and complex set of spatial relationships between its component parts within the bounds of shared enclosing walls. The ability to aggregate individual dwelling units provides the project with an urban structure and a mechanism for relating the domestic to the scale of the public realm.

This typological rigour, and the evocative tactility of the environmental responses pursued in the better of the pavilion proposals, are salient points to draw from the works. Despite the difficulties and limitations, the exhibition has provided a rare opportunity to test architectural ideas physically in a forum unfettered by the mindless ubiquity of market expectation and has reaffirmed the value of experimentation over determinism in the development of our future housing choices.

LAURA HARDING WORKS WITH THE SYDNEY-BASED PRACTICE HILL THALIS ARCHITECTURE + URBAN PROJECTS. HOUSES OF THE FUTURE WAS ALSO DISPLAYED AT THE MELBOURNE DOCKLANDS UNTIL 5 DECEMBER 2004, AND IS NOW AT SYDNEY OLYMPIC PARK FOR THE REST OF 2005.