How Valve got passable VR running on a four-year-old graphics card (original) (raw)

Adaptive quality scaling automatically maximizes VR performance on any hardware.

That green box in the middle of this Aperture Science scene indicates it's running right in the middle of the adaptive performance curve. Credit: Alex Vlachos

That green box in the middle of this Aperture Science scene indicates it's running right in the middle of the adaptive performance curve. Credit: Alex Vlachos

Officially, Valve's SteamVR performance test seems to require a high-powered Nvidia GTX 970 graphics card or better for high-quality "VR ready" performance. At a GDC talk last week, though, Valve Graphics Programmer Alex Vlachos detailed how a number of adaptive quality programming tricks let him run Valve's impressive Aperture Science VR demo passably on a four-year-old Nvidia GTX 680.

That's especially impressive because VR graphics can often push even high-end graphics cards to their limits. In virtual reality, the graphics hardware has to push two separate views (one for each eye) at a rock-solid 90 frames per second to avoid a nauseating delay between head movement and the view shown on the display. That leaves the graphics card only 11.1 ms per frame to render what can be complex 3D scenes.

The VR environment also means the user can often move the first-person "camera" (i.e. their head) wherever they want, as fast as they want. Unlike a standard first-person engine, which usually displays the world only at standing or crouching height, a free-roaming VR engine needs to be potentially ready to display any object from any distance and any angle, rendering it quickly at a convincing level of detail. And a VR engine can't just slow to a crawl when scenes get crowded or complicated, either. Remember, dipping below 90 fps can be literally sickening.

In the past, VR engines have dealt with this problem using tricks like reprojection. If a complex scene meant a frame wasn't ready in time, the engine could run a quick transformation on the previous frame, reprojecting the old image to estimate what the scene might look like at a new head position and angle. That gives the engine some time to catch up with itself, but it's an imperfect solution that can lead to juddery images that look out-of-focus (especially if the trick is used frequently). Vlachos urged developers only to use this as "a last resort safety net" and not to rely on that technique unless the game is running on hardware well below the minimum specifications.

You have to learn to adapt

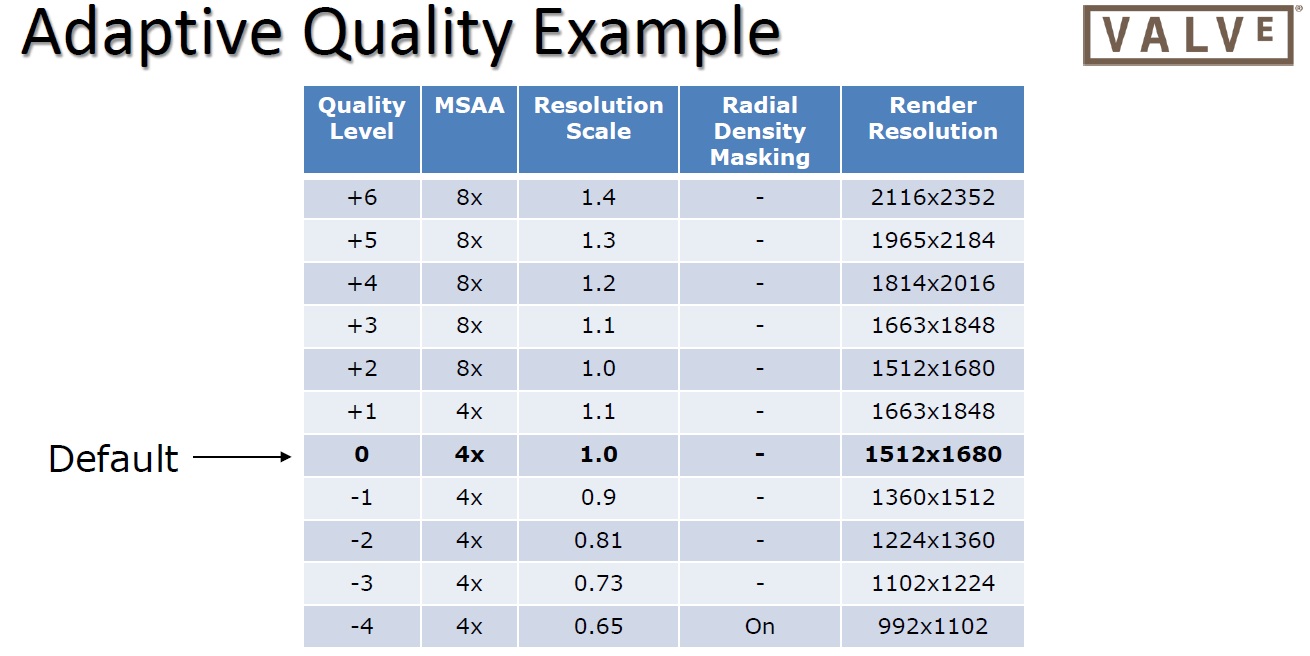

By traveling up and down this scale automatically as needed, a VR engine can maximize GPU usage while maintaining a solid 90 frames per second.

By traveling up and down this scale automatically as needed, a VR engine can maximize GPU usage while maintaining a solid 90 frames per second. Credit: Alex Vlachos

A better solution, as Vlachos laid out in detail in his GDC talk, is adaptive quality adjustment. This basically means that the system monitors the processing time for each rendered frame and immediately lowers or raises the quality of the rendering based on how much headroom is available for that scene.

If the user is looking at a relatively plain and detail-free wall, for instance, the engine can temporarily jack up the image quality to take advantage of all the extra available processing time. When looking at the complicated innards of an Aperture robot, though, the engine would need to quickly dial back the quality to maintain that 90 frames-per-second performance. The goal is to use 70 to 90 percent of the GPU's power at all times while always pushing out frames in that tight 11.1 ms window (though Vlachos says operating within 10 ms is better to leave some GPU resources for the rest of the system).

Certain graphical features can't really be comfortably altered using this adaptive method; the user would probably notice if specular reflections or shadows suddenly popped on and off as they moved around in VR. But the engine can comfortably scale its rendering resolution and viewport size slowly up and down without any jarring effects. The level of detail in edge-smoothing features like multisample anti-aliasing (MSAA) can also be tweaked on the fly relatively easily.

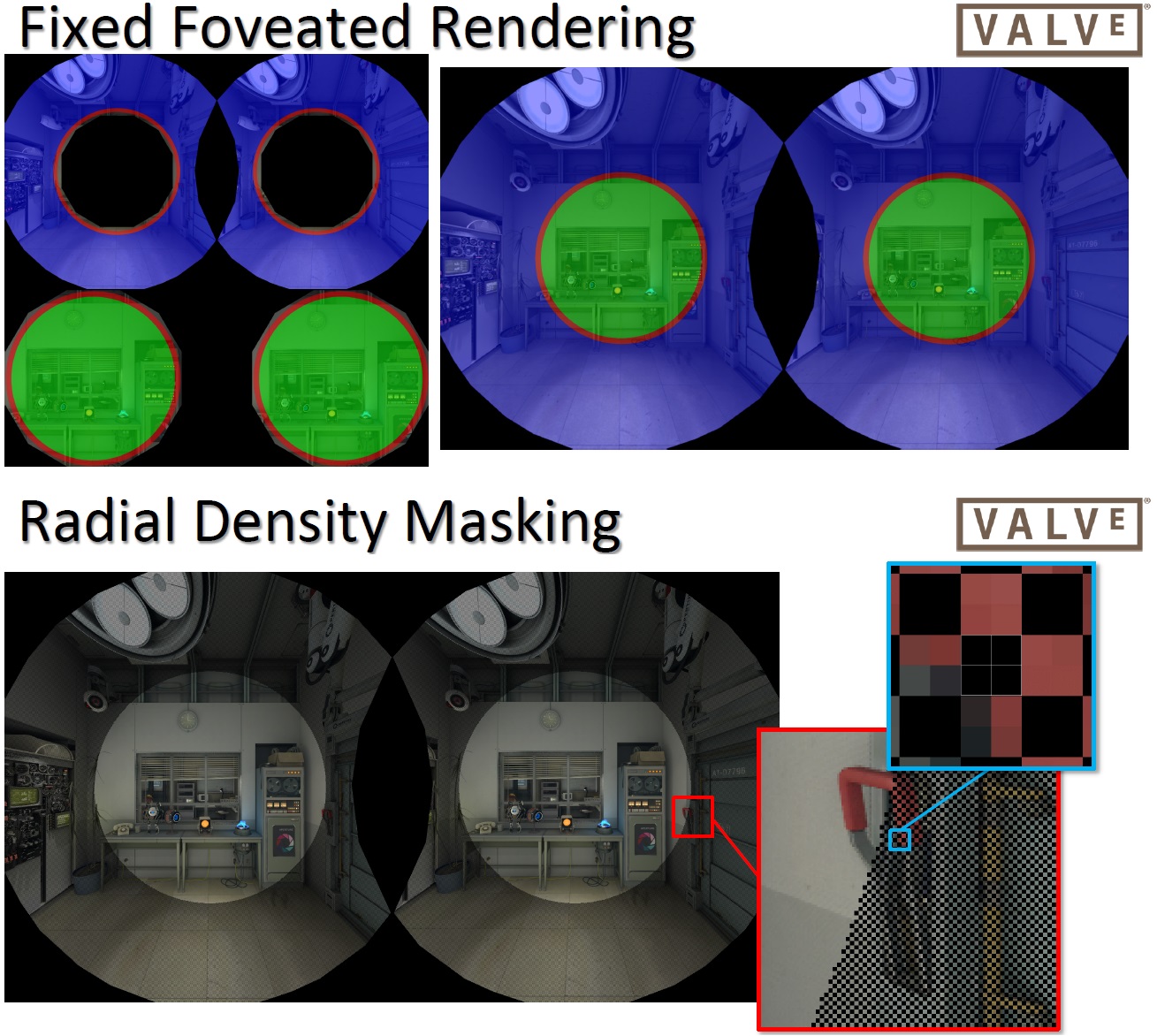

Graphical explanation of two methods that can improve processing time for VR scenes.

Graphical explanation of two methods that can improve processing time for VR scenes. Credit: Alex Vlachos

At the very far edges of the performance curve, the engine can even pull off some VR-specific graphics tricks to ensure rendered frames are ready on time. Using fixed foveated rendering, for instance, the engine can lower the apparent resolution in a ring around the edge of each eye's circular VR view. Radial density masking similarly skips rendering alternating pixels near the edge of the player's vision, filling them in based on their neighbors instead. These tricks save a lot of processing time—enough for a 10- to 25-percent performance improvement on their own, Vlachos said—while also mirroring our eyes' natural tendency to see objects in more detail near the center of our vision.

Lowering the VR bar

With all this in mind, Vlachos was able to set a number of stair-step quality levels for Valve's Aperture Science demo. At the high end (achievable reliably only on a top-of-the-line GTX 980Ti card), the demo can run at 140 percent of the default resolution and at enhanced 8x MSAA. At the low end, the resolution drops to 65 percent of the default, MSAA scales back to 4x, and Radial Density Masking is turned on.

With those changes, a demo that was originally designed for a GTX 970 can run with a consistent frame rate on a four-year-old GTX 680 (even if details like text are hard to read at the heavily reduced resolutions required). While that doesn't mean Vlachos is comfortable recommending such old hardware as the new "minimum spec" for SteamVR, providing room for such a harsh test gives artists more room to manage the trade-offs between highly detailed in-game objects and lower rendering resolutions. It also automatically improves how good VR games can look on high-end hardware without the need to spend time writing new shader code or drawing new art assets.

Rather than hoarding this adaptive quality scaling for its own Source 2 engine, Valve will be making it available as a free Unity Engine rendering plug-in in the next few weeks. The hope is that the indie studios making many of the first VR games will be able to make those games look and perform better instantly without much additional work. Technical details aside, it's nice to see Valve doing this kind of low-level work to make sure virtual reality games perform as well as possible right out of the gate.

Kyle Orland has been the Senior Gaming Editor at Ars Technica since 2012, writing primarily about the business, tech, and culture behind video games. He has journalism and computer science degrees from University of Maryland. He once wrote a whole book about Minesweeper.