fossile Archives - ATLANTIS RISING THE RESEARCH REPORT (original) (raw)

A 3D model of a 407-million-year-old plant fossil has overturned thinking on the evolution of leaves. The research has also led to fresh insights about spectacular patterns found in plants.

Leaf arrangements in the earliest plants differ from most modern plants, overturning a long-held theory regarding the origins of a famous mathematical pattern found in nature, research shows.

The findings indicate that the arrangement of leaves into distinctive spirals, that are common in nature today, were not common in the most ancient land plants that first populated the earth’s surface.

Instead, the ancient plants were found to have another type of spiral. This negates a long held theory about the evolution of plant leaf spirals, indicating that they evolved down two separate evolutionary paths.

Whether it is the vast swirl of a hurricane or the intricate spirals of the DNA double-helix, spirals are common in nature and most can be described by the famous mathematical series the Fibonacci sequence.

Named after the Italian mathematician, Leonardo Fibonacci, this sequence forms the basis of many of nature’s most efficient and stunning patterns.

Spirals are common in plants, with Fibonacci spirals making up over 90% of the spirals. Sunflower heads, pinecones, pineapples and succulent houseplants all include these distinctive spirals in their flower petals, leaves or seeds.

Why Fibonacci spirals, also known as nature’s secret code, are so common in plants has perplexed scientists for centuries, but their evolutionary origin has been largely overlooked.

Based on their widespread distribution it has long been assumed that Fibonacci spirals were an ancient feature that evolved in the earliest land plants and became highly conserved in plants.

However, an international team led by the University of Edinburgh has overthrown this theory with the discovery of non-Fibonacci spirals in a 407-million-year old plant fossil.

Using digital reconstruction techniques the researchers produced the first 3D models of leafy shoots in the fossil clubmoss Asteroxylon mackiei – a member of the earliest group of leafy plants.

The exceptionally preserved fossil was found in the famous fossil site the Rhynie chert, a Scottish sedimentary deposit near the Aberdeenshire village of Rhynie.

The site contains evidence of some of the planet’s earliest ecosystems – when land plants first evolved and gradually started to cover the earth’s rocky surface making it habitable.

The findings revealed that leaves and reproductive structures in Asteroxylon mackiei, were most commonly arranged in non-Fibonacci spirals that are rare in plants today.

This transforms scientists understanding of Fibonacci spirals in land plants. It indicates that non-Fibonacci spirals were common in ancient clubmosses and that the evolution of leaf spirals diverged into two separate paths.

The leaves of ancient clubmosses had an entirely distinct evolutionary history to the other major groups of plants today such as ferns, conifers and flowering plants.

The team created the 3D model of Asteroxylon mackiei, which has been extinct for over 400 million years, by working with digital artist Matt Humpage, using digital rendering and 3D printing.

The research was published in the journal Science (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adg4014).

AR #100

Divine Proportions

by Patrick Marsolek

https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/1087828937

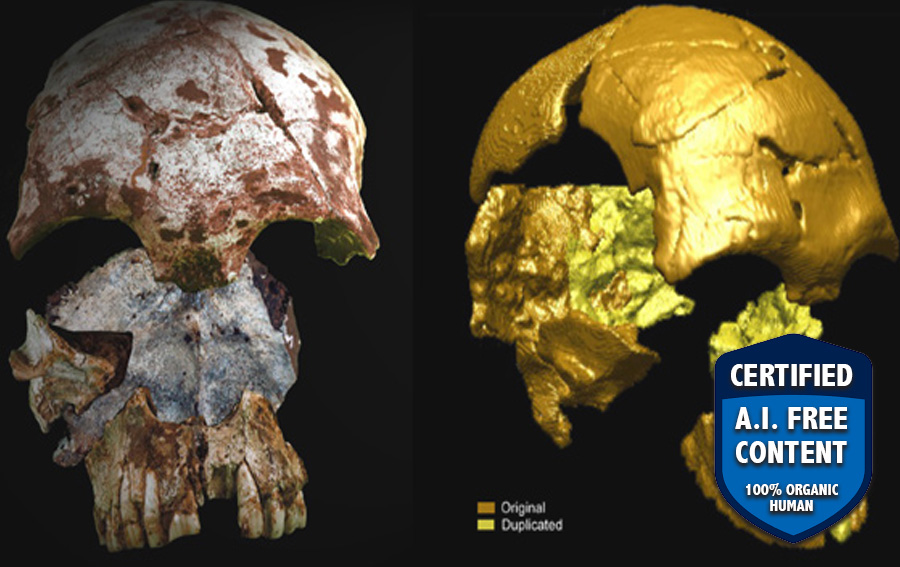

Fifteen years of archaeology in the Tam Pa Ling cave in northeastern Laos has yielded a reliable chronology of early human occupation of the site, scientists report in the journal Nature Communications. Excavations through the layers of sediments and bones that gradually washed into the cave and were left untouched for tens of thousands of years reveals that humans lived in the area for at least 70,000 years – and likely even longer. (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-38715-y)

“When we first started excavating the cave, we never expected to find humans in that region,” said University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign anthropology professor Laura Shackelford, who led the research with Fabrice Demeter, a professor of anthropology at the University of Copenhagen. “But beginning that first season when we started work there, we found our first modern humans. At the time, that made them the only early modern human fossils in the region.”

While the remains of modern Homo sapiens dating back roughly 197,000 years have been recovered in Israel, genetic studies suggest the main phase of early human migration out of Africa and into Asia occurred much later – around 50,000 years ago, Shackelford said. Her team’s earliest excavations in Tam Pa Ling found bone fragments from modern human remains dating to about 40,000 years ago. But as the excavations dug deeper, the age of sediments and animal remains found alongside human bones dated back much earlier.

In 2019, the team had excavated as far as they could in the cave, reaching bedrock about 23 feet (7 meters) below the surface. The excavations yielded dozens of animal bones and many fragments of human skeletal remains. The deepest human bone recovered – a partial tibia – was resting on bedrock near the bottom of the trench. Analyses of sediments taken not far above this bone indicate the soil was deposited there between 67,000 and 90,000 years ago.

The excavation of Tam Pa Ling cave involved digging a 23-foot (7-meter) trench from the surface of the cave to bedrock while painstakingly collecting and documenting the soils, animal bones and human bones discovered there.

“The entire section of the trench goes from about 30,000 years ago to 80,000 to 100,000 years ago,” Shackelford said. “Flood season after flood season, the sediments and bones washed into the cave and were deposited. They’ve been sitting there ever since.”

AR #110

Exploring Indonesia’s Bada Valley

by David Hatcher Childress

New observations and excavations in South African caves have found that Homo naledi, an early human ancestor, intentionally buried their dead and made crosshatch engravings in the cave walls nearby, 100,000 years before humans, almost 300,000 years ago (https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.06.01.543135v1).

Fossils of Homo naledi were first discovered in these caves 10 years ago. The new findings,, are now the earliest evidence of mortuary and meaning-making behaviors in human ancestors. Until now, scholars believed that the mental capacity behind complex cultural behaviors like burial and mark-making required a larger brain, like those of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. And yet, Homo naledi’s brain was only about one-third the size of humans’.

“It’s not how big your brain is, it’s how you use it and what it’s structured for,” says Hawks, an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison who has helped lead the Homo naledi team since the beginning.

Not only did H. naledi have a smaller brain, but the species also had a smaller frame than their human cousins. Based on the skeletons they have excavated, archaeologists estimate the average H. naledi individual weighed less than 90 pounds and stood under 5 feet tall. That would make navigating the narrow, cramped passageways of the Rising Star Cave System where their remains have been found easy for H. naledi. But for human archaeologists and researchers, the cave site is a challenging environment to study and excavate.

The chambers where the burials and crosshatch markings were found are in the Dinaledi subsystem of the cave, about 50 meters from the main entrance where archaeologists shimmy in. The team found two burial sites, one near the entrance to the subsystem and another further back in another chamber. While limestone does erode and crack over time, Hawks says that those natural patterns tend to be easily recognized by their complex “elephant skin” texture. Instead, the artificial engravings are a few bold lines on a mostly flat surface, made of multiple striations that appear to have been made with a tool.

For Hawks, the most convincing line in the panel occurs near a spot in the limestone that has a natural waved texture due to older algae fossils in the walls. The lines making up these parts of the engravings are irregular and appear to have been gone over again and again, as if their creator were persistently trying to etch the markings in as they were diverted by the bumpy texture on the wall.

“That’s not natural,” Hawks says. “That, to me, is really convincing that somebody was making these, and where the rock gets uneven, they had more difficulty controlling and keeping the mark in the same line.”

he Archaic period.

AR #131

Tiny Prehistoric Brains Make Big Trouble for Science

Fossilized fragments of a skeleton, hidden within a rock the size of a grapefruit, have helped upend one of the longest-standing assumptions about the origins of modern birds.

Researchers Researchers from the University of Cambridge and the Natuurhistorisch Museum Maastricht have found evidence that one of the key skull features that characterizes 99% of modern birds – a mobile beak – evolved before the mass extinction event that killed all large dinosaurs, 66 million years ago (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-05445-y).

This finding also suggests, say the scientists, that the skulls of ostriches, emus and their relatives evolved ‘backwards’, reverting to a more primitive condition after modern birds arose.

Using CT scanning techniques, the Cambridge team identified bones from the palate, or the roof of the mouth, of a new species of large ancient bird, which they named Janavis finalidens. It lived at the very end of the Age of Dinosaurs and was one of the last toothed birds to ever live. The arrangement of its palate bones shows that this ‘dino-bird’ had a mobile, dexterous beak, almost indistinguishable from that of most modern birds.

For more than a century, it had been assumed that the mechanism enabling a mobile beak evolved after the extinction of the dinosaurs. However, the new discovery, reported in the journal Nature, suggests that our understanding of how the modern bird skull came to be needs to be re-evaluated.

Each of the roughly 11,000 species of birds on Earth today is classified into one of two over-arching groups, based on the arrangement of their palate bones. Ostriches, emus and their relatives are classified into the palaeognath, or ‘ancient jaw’ group, meaning that, like humans, their palate bones are fused together into a solid mass.

All other groups of birds are classified into the neognath, or ‘modern jaw’ group, meaning that their palate bones are connected by a mobile joint. This makes their beaks much more dexterous, helpful for nest-building, grooming, food-gathering, and defence.

The two groups were originally classified by Thomas Huxley, the British biologist known as ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ for his vocal support of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. In 1867, he divided all living birds into either the ‘ancient’ or ‘modern’ jaw groups. Huxley’s assumption was that the ‘ancient’ jaw configuration was the original condition for modern birds, with the ‘modern’ jaw arising later.

“This assumption has been taken as a given ever since,” said Dr Daniel Field from Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences, the paper’s senior author. “The main reason this assumption has lasted is that we haven’t had any well-preserved fossil bird palates from the period when modern birds originated.”

The fossil, Janavis, was found in a limestone quarry near the Belgian-Dutch border in the 1990s and was first studied in 2002. It dates from 66.7 million years ago, during the last days of the dinosaurs. Since the fossil is encased in rock, scientists at the time could only base their descriptions on what they could see from the outside. They described the bits of bone sticking out from the rock as fragments of skull and shoulder bones, and put the unremarkable-looking fossil back in storage.

https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/the-last-toothed-bird

AR #128

Akhenaten, the Bird King

by Jonathon Perrin

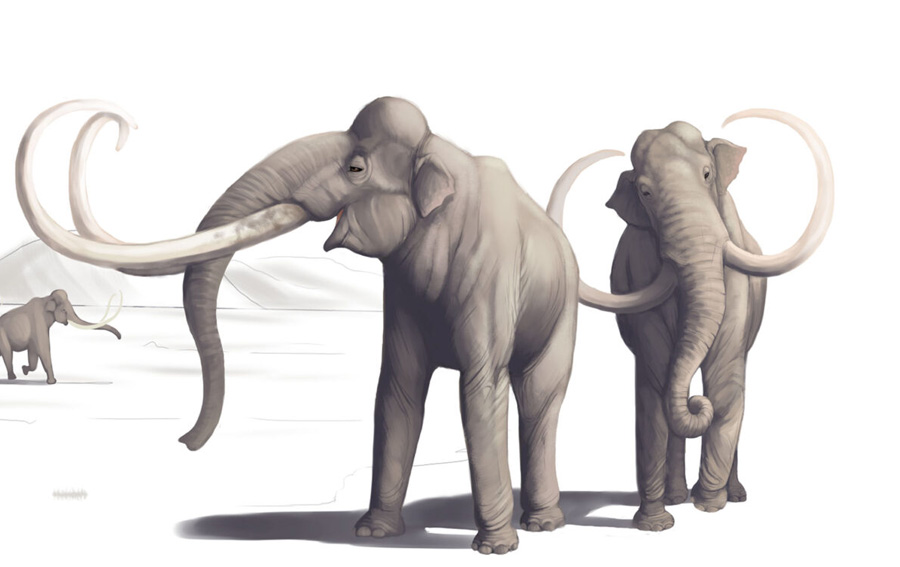

About 37,000 years ago, a mother mammoth and her calf met their end at the hands of human beings.

Bones from the butchering site record how humans shaped pieces of their long bones into disposable blades to break down their carcasses, and rendered their fat over a fire. But a key detail sets this site apart from others from this era. It’s in New Mexico – a place where most archaeological evidence does not place humans until tens of thousands of years later.

A recent study led by scientists with The University of Texas at Austin finds that the site offers some of the most conclusive evidence for humans settling in North America much earlier than conventionally thought.

The researchers revealed a wealth of evidence rarely found in one place. It includes fossils with blunt-force fractures, bone flake knives with worn edges, and signs of controlled fire. And thanks to carbon dating analysis on collagen extracted from the mammoth bones, the site also comes with a settled age of 36,250 to 38,900 years old, making it among the oldest known sites left behind by ancient humans in North America.

“What we’ve got is amazing,” said lead author Timothy Rowe, a paleontologist and a professor in the UT Jackson School of Geosciences. “It’s not a charismatic site with a beautiful skeleton laid out on its side. It’s all busted up. But that’s what the story is.”

The findings were published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

Rowe does not usually research mammoths or humans. He got involved because the bones showed up in his backyard, literally. A neighbor spotted a tusk weathering from a hillslope on Rowe’s New Mexico property in 2013. When Rowe went to investigate, he found a bashed-in mammoth skull and other bones that looked deliberately broken. It appeared to be a butchering site. But suspected early human sites are shrouded in uncertainty. It can be notoriously difficult to determine what was shaped by nature versus human hands.

This uncertainty has led to debate in the anthropological community about when humans first arrived in North America. The Clovis culture, which dates to 16,000 years ago, left behind elaborate stone-wrought tools. But at older sites where stone tools are absent, the evidence gets more subjective, said retired Texas State University Professor Mike Collins, who was not involved with this paper and who oversaw research at Gault, a well-known archaeological site near Austin with an abundance of Clovis and pre-Clovis artifacts.

Although the mammoth site lacks clearly associated stone tools, Rowe and his co-authors discovered an array of supporting evidence by putting samples from the site through scientific analyses in the lab.

Based on genetic evidence from Indigenous populations in South and Central America and artifacts from other archaeological sites, some scientists have proposed that North America had at least two founding populations: the Clovis and a pre-Clovis society with a different genetic lineage.

The researchers suggest that New Mexico site, with its age and bone tools instead of elaborate stone technology, may lend support to this theory. Collins said the study adds to a growing body of evidence for pre-Clovis societies in North America while providing a toolkit that can help others find evidence that may have been otherwise overlooked.

The research was funded by the Jackson School, the National Science Foundation, and the W.J.J. Gordon Foundation.

AR #108

Calico, California and the Early Man Dispute

by Michael Cremo

Fossils of small plesiosaurs, long-necked marine reptiles from the age of dinosaurs, have been found in a 100-million year old river system that is now Morocco’s Sahara Desert. This discovery suggests some species of plesiosaur, traditionally thought to be sea creatures, may have lived in freshwater.

Plesiosaurs, first found in 1823 by fossil hunter Mary Anning, were prehistoric reptiles with small heads, long necks, and four long flippers. They inspired reconstructions of the Loch Ness Monster, but unlike the monster of Loch Ness, plesiosaurs were marine animals – or were widely thought to be.

Now, scientists from the University of Bath and University of Portsmouth in the UK, and Université Hassan II in Morocco, have reported small plesiosaurs from a Cretaceous-aged river in Africa, in the journal Cretaceous Research.

The fossils include bones and teeth from three-meter long adults and an arm bone from a 1.5 meter long baby. They hint that these creatures routinely lived and fed in freshwater, alongside frogs, crocodiles, turtles, fish, and the huge aquatic dinosaur Spinosaurus.

These fossils suggest the plesiosaurs were adapted to tolerate freshwater, possibly even spending their lives there, like today’s river dolphins.

“It’s scrappy stuff, but isolated bones actually tell us a lot about ancient ecosystems and animals in them. They’re so much more common than skeletons, they give you more information to work with” said Dr. Nick Longrich, corresponding author on the paper.

“The bones and teeth were found scattered and in different localities, not as a skeleton. So each bone and each tooth is a different animal. We have over a dozen animals in this collection.”

Whilst bones provide information on where animals died, the teeth are interesting because they were lost while the animal was alive – so they show where the animals lived.

What’s more, the teeth show heavy wear, like those fish-eating dinosaur Spinosaurus found in the same beds.

The scientists say that implies the plesiosaurs were eating the same food- chipping their teeth on the armored fish that lived in the river. This hints they spent a lot of time in the river, rather than being occasional visitors.

While marine animals like whales and dolphins wander up rivers, either to feed or because they’re lost, the number of plesiosaur fossils in the river suggest that’s unlikely.

A more likely possibility is that the plesiosaurs were able to tolerate fresh and salt water, like some whales, such as the beluga whale.

It’s even possible that the plesiosaurs were permanent residents of the river, like modern river dolphins. The plesiosaurs’ small size would have let them hunt in shallow rivers, and the fossils show an incredibly rich fish fauna.

Dr Longrich said: “We don’t really know why the plesiosaurs are in freshwater.

“It’s a bit controversial, but who’s to say that because we paleontologists have always called them ‘marine reptiles’, they had to live in the sea? Lots of marine lineages invaded freshwater.”