Phil Lesh - Rolling Stone Australia (original) (raw)

July 2, 2020 12:27PM

The 50 Greatest Bassists of All Time

From funk masters to prog prodigies and beyond, we count down the players who have shaped our idea of the low-end theory

JONATHAN BERNSTEIN & DAVID BROWNE & JON DOLAN & BRENNA EHRLICH & DAVID FEAR & JON FREEMAN & ANDY GREENE & KORY GROW & ELIAS LEIGHT & ANGIE MARTOCCIO & JASON NEWMAN & ROB SHEFFIELD & HANK SHTEAMER & SIMON VOZICK-LEVINSON

We count down the 50 greatest bassists of all time, from string-popping virtuosos to steady session heroes.

Photographs used in illustration by AP/Shutterstock; Joseph Okpako/WireImage; Elaine Thompson/AP/Shutterstock

“The bass is the foundation,” session legend Carol Kaye once said, “and with the drummer you create the beat. Whatever you play puts a framework around the rest of the music.”

A great bass line, whether it’s Paul McCartney’s hypnotic “Come Together” riff, Bootsy Collins’ sly vamp from James Brown’s “Sex Machine,” or Tina Weymouth’s minimal throb on Talking Heads’ “Psycho Killer,” is like a mantra: It sounds like it could go on forever, and it only feels more profound the more you hear it. Guitarists, singers, and horn players tend to claim the flashiest moments in any given song, while drummers channel most of the kinetic energy, but what the bassist brings is something elemental — the part that loops endlessly in your head long after the music ends.

Bassists are often overlooked and undervalued, even within their own bands. “It wasn’t the number-one job,” McCartney once said, reflecting on the fateful moment when he took over the four-string after Stu Sutcliffe exited the Beatles. “Nobody wanted to play bass, they wanted to be up front.”

And yet the instrument has its own proud tradition in popular music, stretching from the mighty upright work of Jimmy Blanton in Duke Ellington’s orchestra and bebop pioneers like Oscar Pettiford to fellow jazz geniuses like Charles Mingus and Ron Carter; studio champs like Kaye and James Jamerson; rock warriors like Cream’s Jack Bruce and the Who’s John Entwistle; funk masters like Bootsy and Sly and the Family Stone’s Larry Graham; prog prodigies like Yes’ Chris Squire and Rush’s Geddy Lee; fusion gods like Stanley Clarke and Jaco Pastorius; and punk and postpunk masters like Weymouth and the Minutemen’s Mike Watt. The alternative era brought new heroes on the instrument, from Sonic Youth’s intuitive Kim Gordon to Primus’ outlandish Les Claypool, and more recently, a fresh crop of bass icons — including Esperanza Spalding and the ubiquitous Thundercat — have placed the low end at the center of their musical universes.

As with our 100 Greatest Drummers list, this rundown of the 50 greatest bassists of all time celebrates that entire spectrum. It’s emphatically not intended as a ranking of objective skill; nor does it assign any one set of criteria as a measure of greatness. Instead it’s an inventory of the bassists who have had the most direct and visible impact on creating, to borrow Kaye’s term, the very foundation of popular music — from rock to funk to country to R&B to disco to hip-hop, and beyond — during the past half-century or so. You’ll find obvious virtuosos here, but also musicians whose more minimal concept of their instrument’s role elevated everything that was going on around them.

“You grab it, slide around on it, and feel it with your hands,” Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Flea once said of his signature instrument. “You slap, pull, thump, pluck, and pop, and you get yourself into this hypnotic state, if you’re lucky, beyond thought, where you’re not thinking because you’re just a conduit for this rhythm, from wherever it comes from, from God to you and this instrument, through a cord and a speaker.”

Here we pay tribute to 50 musicians who have found that same exalted state via the bass, and changed the world in the process.

Bob Minkin/mediapunch/Shutterstock

In the same way that the Grateful Dead reconfigured how a rock band should sound — looser and jammier, incorporating equal parts jazz and country — Phil Lesh made us hear the bass in a new way. The Dead’s founding and longtime bassist grew up on experimental and classical music and played trumpet and violin in high school. He only took up his signature instrument when he was asked to join the Warlocks, the first version of the Dead. As a result, Lesh ignored standard walking-bass clichés: “I didn’t think that would be suitable for the music I would make with Jerry, just to do something somebody else had done,” he said in 2014. His idea — “play bass and lead at the same time,” his notes darting in and around the melody — became as recognizable a part of the Dead’s sound as Garcia’s guitar. His unconventional sound can be heard in studio recordings like “Truckin’,” “Shakedown Street,” and “Cumberland Blues,” the live version of “Scarlet Begonias” from the legendary Cornell 1977 show, and many live versions of “Eyes of the World” (start with 1975’s One From the Vault).

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

“On the bass, that’s my man, Ron Carter,” Q-Tip says proudly on the outro to A Tribe Called Quest’s super-funky Low End Theory track “Verses From the Abstract.” A milestone for the intersection of jazz and hip-hop, the track was just another day at the office for the great Ron Carter, who’s been turning up on history-making sessions for 60 years and counting. With more than 2,200 credits to his name as of fall 2015, he earned a Guinness World Record a year later for the most recorded bassist in jazz history. Beyond the raw numbers, the range of Carter’s CV is astounding, from anchoring the Sixties Miles Davis quintet that reshaped jazz on a molecular level to bringing an unshakable drive to classic Roberta Flack and Aretha Franklin sides, providing a plush rhythmic bed for bossa nova pioneer Antônio Carlos Jobim, and finding the swing in Bach. Whether in a low-key duo or buoyant big band, Carter always adds a touch of pure class. “I think Mr. Carter is one of the consummate listening musicians ever,” said collaborator and lifelong fan Pat Metheny in 2016. “He has played in literally thousands of unique settings and is always able to find something that brings out the best in his associates, while always remaining true to his own very strong sense of identity.”

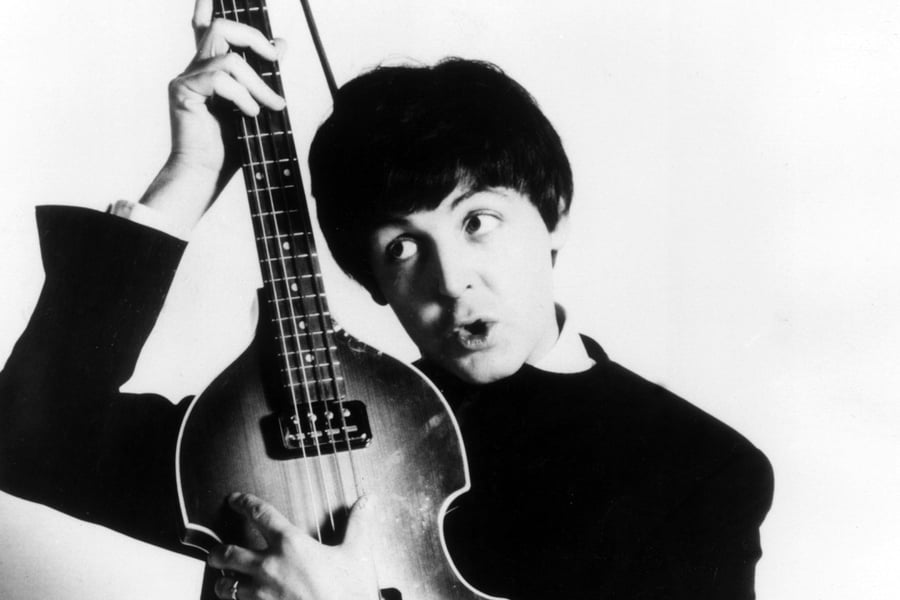

It’s hard to think of Paul McCartney as being underrated in any category. But for all the praise he’s earned as a singer, songwriter, and live performer, it’s quite possible he hasn’t gotten enough for his low-key low-end verve. He first took up the bass as a matter of necessity, after Stu Sutcliffe quit the Beatles in Hamburg in 1961. “There’s a theory that I maliciously worked Stu out of the group in order to get the prize chair of bass,” McCartney told biographer Barry Miles. “Forget it! Nobody wants to play bass, or nobody did in those days.” But he made the instrument his own, particularly as the Beatles’ studio adventures took off in the second half of the Sixties and he switched out his Hofner for a Rickenbacker. McCartney’s bass could be a cool, steady support, as on “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” and “Dear Prudence,” or a colorful lead character in its own right — see “Paperback Writer,” “Rain,” and “A Day in the Life,” all songs where his playing conveys the yearning for a freer or more exciting life behind everyday lyrics. His playful, melodic style in that era owed much to Motown’s James Jamerson, whom he’s often credited as his biggest influence on the instrument; after 1970, McCartney kept up with the times, grooving regally into the disco era with “Silly Love Songs” and “Goodnight Tonight.” And while his interest in the four-string has waned and waxed over the years, he’s never stopped inspiring generations of kids to see the expressive potential of a great bass line.

Ebet Roberts/Getty Images

“My name is John Francis Pastorius III, and I’m the greatest bass player in the world.” That was Jaco Pastorius’ opening line to Joe Zawinul when he met the Weather Report keyboardist backstage at a 1974 Miami show. Zawinul scoffed at the time, but he wasn’t laughing a few years later, once Pastorius had joined the group and helped turn them into bona fide fusion superstars. Jaco’s 1976 self-titled debut, where he played high-speed bebop with ease and dazzled with chiming harmonics, set a new standard for electric-bass virtuosity; joining Weather Report the same year, he thrilled audiences with his signature fretless sound and cocky flair, and forever banished the notion that bass was a background instrument. As flashy a player as he was, he was also a stellar collaborator: From the mid-Seventies through the Eighties — preceding his tragic death at age 35 — Pastorius’ revolutionary four-string approach was a perfect match for everyone from Pat Metheny to Jimmy Cliff, and especially Joni Mitchell’s increasingly adventurous songwriting on albums like Hejira. “[I]t was as if I dreamed him, because I didn’t have to give him any instruction,” Mitchell once said of Jaco. “I could just kind of cut him loose and stand back and celebrate his choices.”

Don Paulsen/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

As a member of Sly and the Family Stone, Larry Graham helped popularize the slap-bass technique with hits like “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” and “Dance to the Music.” He developed the unmissable, percussive approach — Graham calls it “thumpin’ and pluckin’” — while playing in a trio with his mother in San Francisco. When the drummer quit, “I would thump the strings with my thumb to make up for the bass drum, and pluck the strings with my fingers to make up for the backbeat snare drum,” Graham remembered. These lines erupted in Sly and the Family Stone songs, inverting the traditional roles of instruments in popular music and making an indelible impression on future icons like Prince, a friend and frequent collaborator of Graham’s who once called Graham “my teacher.” “If you listen to records from the Fifties, you’ll find that all the melodic information is mixed very loud … and the rhythmic information is mixed rather quietly,” Brian Eno explained in 1983. “From the time of Sly and the Family Stone’s Fresh album, there’s a flip over, where the rhythm instruments, particularly the bass drum and bass, suddenly become the important instruments in the mix.” Graham had a simple explanation for it all: Playing with that much force ensures that “the dancers just won’t hide.”

David Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images

Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker got much of the attention in Cream, but Jack Bruce gave the group the thrust to make them a true power trio. When Clapton would play his soaring blues licks and Baker explored jazzy new strata behind his drum kit, Bruce, also the group’s lead vocalist, kept the band together with heavy bass lines that always seemed to be moving. “Jack Bruce definitely opened my eyes as to what a bass player could do live,” Black Sabbath bassist Geezer Butler once said. “I went to see Cream mainly because of Clapton … and I was mesmerized at Jack Bruce’s playing. I didn’t know a bass player could do those things, filling in where the rhythm guitar would normally be.” Bruce played jittery, tumbling lines under the trio’s group vocals on “I Feel Free,” smart harmonies on “Sunshine of Your Love,” and basically his own riff under Clapton’s on “Strange Brew.” “He was a small guy, but his playing was monstrous,” Mountain guitarist Leslie West, who played with Bruce later, once said. “He made his bass bark, and everything he did was so melodic.”

Jasper Dailey/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Cutting her teeth in Fifties jazz clubs and breaking out as a studio guitarist for hitmakers like Sam Cooke, Kaye went on to become the most recorded bassist of all time — with more than 10,000 tracks under her belt. From the sunny swing of the Beach Boys’ 1965 track “Help Me, Rhonda” to Richie Valens’ now-classic 1958 version of “La Bamba” to Frank and Nancy Sinatra’s romantic 1967 rendition of “Somethin’ Stupid,” Kaye’s fingerprints are all over the history of modern pop. And that’s not even including her myriad movie and TV show themes — she gave the title songs for everything from Batman to Mission Impossible their uniquely groovy backbone. “I was a guitar player, and I thought, ‘God, that’s kind of a simple bass line,’” she told For Bass Players Only of the intuition that helped guide her playing. “I thought the bass could be moving around more and the music would sound better.” Her star collaborators evidently agreed. “He would keep my bass sound way up in the mixes,” she said of Brian Wilson in 2011. “On a song like ‘California Girls,’ at times you can hardly hear anything else. He just liked my sound and the way I moved around the fretboard.”

Fin Costello/Redferns/Getty Images

Bootsy Collins — or “Bootzilla,” “Casper the Friendly Ghost,” or “The World’s Only Rhinestone Rock Star Doll, Baba,” depending on the song — redefined soul and funk bass playing in the Seventies and, by proxy, rap and pop in the Eighties and Nineties. Collins joined James Brown’s backing group, the J.B.’s, in 1970 and immediately latched on to Soul Brother No. 1’s concept of “The One,” hitting the first beat of a musical measure as hard as possible and filling the rest of it with funkiness. Later, he stretched out that concept into a trippy wonderland when he joined George Clinton’s cabal, playing mushy, wah-wah bass in Parliament and Funkadelic before becoming a solo star, fronting his own Rubber Band, wearing star-shaped sunglasses, playing a star-shaped bass, and singing cartoonish love songs with comic-book enthusiasm. You can hear his influence in practically every bass player to come since, from the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Flea to the records Dr. Dre liberally sampled to create the G-Funk sound. “Bootsy came along and all he added … was the emphasis on the one,” George Clinton once said. “You could add that to ‘The ABC’s,’ and it would be funk in two seconds. And from then on, everything we did was funky for real, no matter how pop we tried to be.”

Dezo Hoffman/Shutterstock

The Who’s John Entwistle had a lot of nicknames, including the Ox, due to his imposing build and endless appetites, and the Quiet One, because of his stoic demeanor. But the most apt was one Thunderfingers, a name bestowed upon him because every time he played a note on the bass it sounded like a vicious storm coming over the horizon. It was a style he developed to be heard while playing on the same stage as flamboyant showboats Keith Moon and Pete Townshend, but he brought a remarkable fluidity and grace to his role that was unlike anything anyone had ever heard before. Simply put, he treated the bass like a lead instrument and made it stand out as much as any guitar. And his chunky solo on “My Generation” inspired countless teenagers to pick up the bass, though emulating his playing was a near-impossible task. “Entwistle was arguably the greatest rock bassist of them all,” said Rush’s Geddy Lee, “daring to take the role and sound of the bass guitar and push it out of the murky depths while strutting those amazing chops.”

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

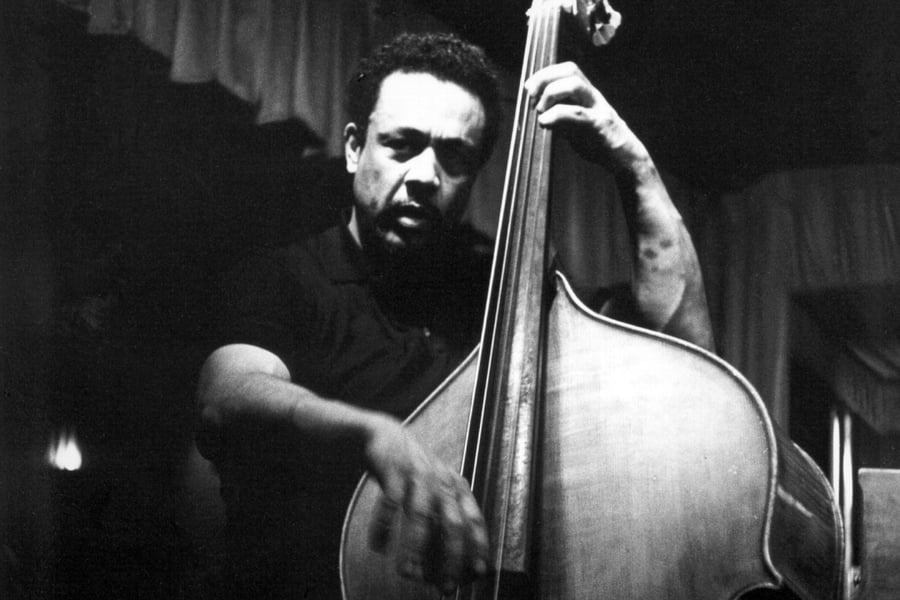

Charles Mingus was so much more than a bass player — composer, conceptualist, classically trained cellist, social critic — that it’s sometimes easy to forget how much of a force he was on his instrument. But at the heart of his lush, kaleidoscopic pieces was a relentless rhythmic drive that flowed from his fingers through the strings and directly into his bands, making it sound as though the soloists were jumping on a giant trampoline. Listen to him chugging away on classic compositions like “II B.S.” and “Better Get Hit in Your Soul,” aligning with drummer and musical soulmate Dannie Richmond, and you’ll get a sense of the strength and grace of his playing, the way he could make a walking line sound both hulking and nimble. Mingus’ career spanned multiple eras of jazz, and his command on the instrument made stylistic divisions seem irrelevant: That’s why he sounds equally at home swinging with Lionel Hampton’s big band in the late Forties (on his own “Mingus Fingers”), jamming with fellow bebop royalty in the Fifties (on the famed Jazz at Massey Hall album, which featured bass parts overdubbed in the studio by the famously exacting Mingus), and carrying on a lively, percussive conversation with his musical idol Duke Ellington in the Sixties (on the immortal Money Jungle). Though he was known mainly for his contribution to jazz, he was never bound by it, as shown by his collaboration with Joni Mitchell and his influence on Sixties rock greats like Jack Bruce and Charlie Watts. Throughout his life, Mingus constantly spoke out against those would tried to limit or underestimate his artistry. Commenting on the unfairness of jazz critics’ polls, he once said, “I don’t want none of them damn polls. I know what kind of bass player I am.”

James Jamerson anchored the Motown rhythm section, expanding the possibilities for bass players with hit after hit after hit, all while remaining mostly anonymous, because session players were rarely credited on Sixties Motown recordings. “James Jamerson became my hero,” Paul McCartney once said, “although I didn’t actually know his name until quite recently.” When Jamerson started his career, the bass was largely seen as a utilitarian support instrument; most players stuck to “stagnant two beat, root-fifth patterns and post–’Under the Boardwalk’ clichéd bass lines,” according to Standing in the Shadows of Motown: The Life and Music of Legendary Bassist James Jamerson. Jamerson helped revolutionize the field, jolting his parts with extra syncopation, additional chords that added melodic depth and complexity, and tonal choices that evoked gospel harmony. His list of contributions to iconic records is impossible to sum up quickly, but his key Motown recordings include the Temptations’ “My Girl,” which surely has one of the most recognizable, instantly gratifying bass parts in all of pop; Gladys Knight’s “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” where he plays a suave, bubbly counter to the jittery piano; and Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” which finds Jamerson at his hyper-melodic best. “James went a step beyond what bassists normally do,” explained Bob Babbitt, who also played bass on several What’s Going On tracks. “At first he took chances and let himself go, and then it just became natural for him, and in the process he changed the course of bass playing.”