Improved Posture for Bigger Lifts and Better Exercise (original) (raw)

Many people — athletes or not — spend much of their days sitting at a desk, hunched over a computer for their jobs. Sitting all day like this might pay the bills, but it often comes at an additional cost: posture. Specifically, forward head and shoulder posture can put a lot of excess stress on the spine, causing discomfort. (1)

It may come as a surprise that even the slightest adjustments to the way you sit at your desk or the desk’s position can have huge benefits for your posture. For example, raising your desk to a 10-degree incline rather than remaining flat can decrease the maximal load on your cervical and thoracic spine by 35 percent and 95 percent, respectively. (2)

Poor posture can negatively impact an athlete’s performance in the gym in more ways than getting into proper positioning for compound movements. Any work-related task poses the risk of back pain when performed in non-ergonomic positions. (3)

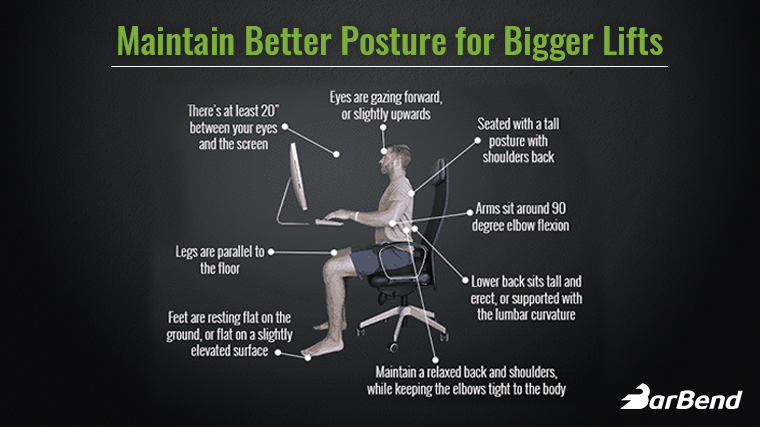

Not every company has the resources to offer employees stand-up desks to promote health, increasing short-term task engagement without hindering work performance. (4) So, if you find yourself in this difficult position (no pun intended), then consider the seated posture tips below to better your desk ergonomics.

Posture Tips for Desk Workers

The way we fixate our eyes can play a big part in our head’s position and posture. When a screen is lower than our line of vision, the head tends to crane forward to view it clearly, thereby arching the neck and applying pressure to the cervical spine. This can lead to neck pain and tight traps. Of course, those lingering effects can negatively impact an athlete’s performance in the gym.

Fortunately, this particular issue can be solved by altering the angle of the visual target (i.e., the screen). The body’s position will serve to complement the eye position. So change where the eye looks, and the posture will follow. (5)

Eye Gaze Path

Fixate your eyes on screens that sit in front of your eyes equal or slightly below the horizontal height. The goal is to decrease the time spent looking down in a forward, flexed neck posture. Ideally, making this correction will lead to a habitual change that can correct poor posture over time. (6)

Screen Distance and Brightness

Extending your arm is an easy way to gauge the appropriate distance between yourself and the computer screen. Twenty-five inches between your eyes and the target screen can help alleviate eyestrain.

Image via Shutterstock/GaudiLab

To reduce the inclination to lean forward, the screen should be adequately bright with ambient light. Closer viewing distances lead to greater eyestrain, particularly when looking at a screen for at least 60 minutes. (7) An tactic you can employ that has shown promising results combating eyestrain is known as the 20-20-20 rule. It requires looking at something 20 feet away from your screen for 20 seconds every 20 minutes. (8)

Chair Position & Joint Angles

Your chair should have a few adjustments to support joint angles that allow you to prevent compromising postures. For example, a chair should not be so high that it leaves your legs dangling. It also should not be so low that your hips are overly flexed. An adjustable chair can vary its height to prevent the hips from remaining in the same position for extended periods. Ideally, a neutral position is maintained during longer seated work periods — thighs sit parallel with the floor — as discomfort as shown to increase for upward and backward positions versus a neutral position (9)

Arm Rests, Chair Back

Your arm rests should support the arms and create a 90-degree angle at the elbow. If your chair doesn’t have arm rests, position the arms so they’re lying at the height of the desk and allow the shoulders to remain relaxed rather than rolled forward. This can help avoid the traps from tightening up, which can cause unwanted tension.

Stagger out times when you sit erect with a tall posture using no support. When using the back of the chair, sit all the way back in the seat and ensure the lumbar curvature is supported. For those curious, the posture is a matter of support rather than the chair itself. For example, spine curvature after 30 minutes is essentially the same across seating types, be it a desk chair, a box, a stability ball, etc. (10)

Support Your Needs

If you are someone who has to get up from your desk routinely, a stand-stool or other similar chair that sits at a naturally higher position is recommended. This can decrease the effort needed to stand from a compromised position (arched back, forward head). (11)

Kinesiology Taping for Posture

Another easy way to promote good posture is with the light use of kinesiology tape. The easiest way to tape the body for better posture is by placing one piece over the scapulas. Doing this will give the mind a stimulus to pull the scapulas back and maintain an upright chest throughout the day, promoting a healthier posture.

Sitting for extended periods of time is likely inevitable, especially for those working sedentary jobs. Fortunately, there are ways to combat the poor posture that sitting for long periods can cause.

The above tips are only a few ways you can work with equipment at your desk to support proper posture. The main takeaways are to raise your computer screen to be horizontal to your eye line or just slightly below, maintain a neutral position for the hips and arms, and keep your shoulders relaxed and back. Hopefully, this will prevent or alleviate any pain or tension in the back and help you lead more productive days at work.

References

- M L Langford. Poor posture subjects a worker’s body to muscle imbalance, nerve compression. 1994. Occupational Health and Safety. Sep;63(9):38-40, 42.

- M de Wall. The effect on sitting posture of a desk with a 10-degree inclination for reading and writing. 1991. Ergonomics. doi: 10.1080/00140139108967338.

- Janusz Nowotny. Body posture and syndromes of back pain. 2011. Ortopedia, Traumatologia, Rehabilitacja. doi: 10.5604/15093492.933788.

- Laura E. Finch, et al. Taking a Stand: The Effects of Standing Desks on Task Performance and Engagement. 2017. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080939.

- M B Villanueva, et al. Adjustments of posture and viewing parameters of the eye to changes in the screen height of the visual display terminal. 1996. Ergonomics.

- Leon M. Straker, et al. Computer Use and Habitual Spinal Posture in Australian Adolescents. 2007. Public Health Reports. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200511.

- Jennifer Long, et al. Viewing distance and eyestrain symptoms with prolonged viewing of smartphones. 2017. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12453.

- Swapndeep Singh Atwal, et al. Health Issues among Radiologists: Toll they Pay to their Profession. 2017. Journal of Clinical & Diagnostic Research. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/17023.9537.

- Rachita Verma, et al. Effect of seat positions on discomfort, muscle activation, pressure distribution and pedal force during cycling. 2016. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2016.02.003.

- J Robinson, et al. A comparative study of the stability ball vs. the desk chair in healthy young adults: sagittal curvature, sitting duration and usability. 2009. Scoliosis. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-4-S2-O33.

- U P Arborelius, et al. The effects of armrests and high seat heights on lower-limb joint load and muscular activity during sitting and rising. 1992. Ergonomics. doi: 10.1080/00140139208967399.

Featured image via Shutterstock/Marcin Balcerzak