Remembering Grace Hopper – Communications of the ACM (original) (raw)

She had a habit of bucking convention and espoused the motto, “It's always easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.”

The second week of each December, Computer Science Education Week introduces K-12 students to computer science. This timing was chosen to commemorate the birthday of Grace Murray Hopper, December 9, 1906.

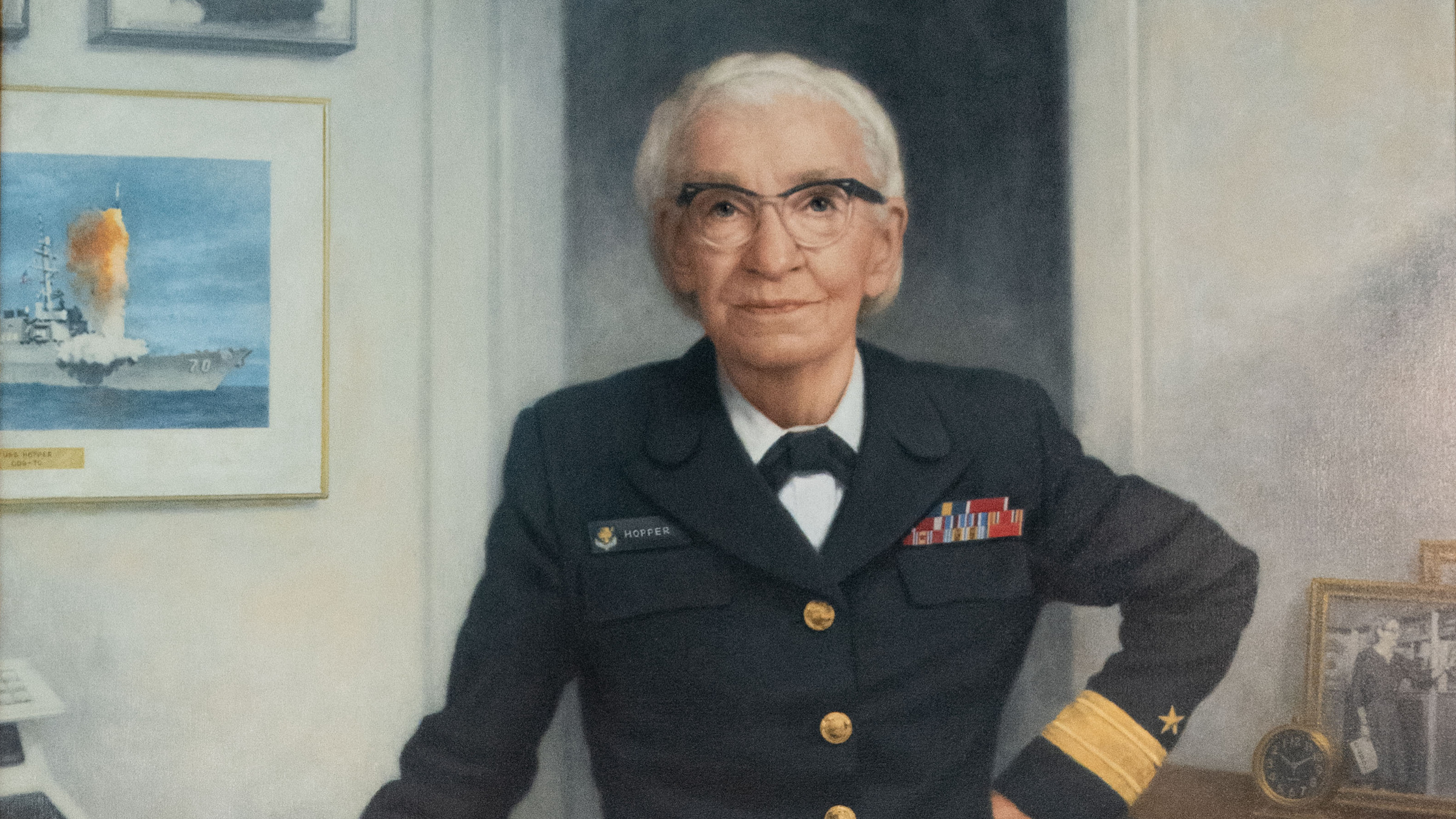

Rear Admiral Hopper is well known to the CS community for her many contributions to computing. For those who never saw her, I recommend her 1986 television appearance on ‘Late Night with David Letterman’ where her personality shines through. Her Wikipedia page provides a good overview of her many accomplishments; the books Grace Hopper and the Invention of the Information Age (MIT Press, 2009) by Kurt W. Beyer, and Grace Hopper: Admiral of the Cyber Sea (Naval Institute Press, 2004) by Kathleen Broome Williams, provide more in-depth studies.

Rear Admiral Hopper died in 1992, and not long ago, my wife and I decided to track down her grave site. She is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, which overlooks the Potomac River, just west of Washington DC. Within the cemetery are Arlington House (family home of Robert E. Lee), the John F. Kennedy Memorial, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, and many other memorials. The cemetery spans 639 acres (about 2.6 km2) and is home to over 400,000 grave sites; it is a somber place to visit.

Credit: Joel C. Adams

To locate the grave of an individual, the cemetery maintains a find-a-grave app. Entering ‘Grace Hopper’ into this app reveals that she is buried in section 59, grave 973.

The cemetery also provides a map to help visitors navigate the space; if you park near the main entrance, proceed down Memorial Drive through the main gates, turn left on Eisenhower Drive, proceed about ¼ mile, and section 59 will be on your left. Each gravestone has its section and grave numbers on the back; a short search led us to stone number 973 in section 59.

Credit: Joel C. Adams

Hopper’s life is a story of overcoming obstacles. A gifted woman in a predominately male field, she was the first woman to earn a Ph.D. in mathematics from Yale in 1934. Afterwards, she taught mathematics at Vassar (where she had earned her bachelor’s degree) until the U.S. entered World War II. Being from a Navy family, she tried to join the Navy but at age 34, she was rejected as too old. She turned to the Naval Reserve; joining it required her to acquire a special waiver because her weight (105 pounds, ~47 kg) was well below the Navy’s 120 pound minimum. She graduated from midshipman’s school first in her class, earning her commission as a lieutenant.

The Navy assigned her to the Bureau of Ships Computation Project at Harvard to program its Mark I computer, also known as the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator. As one of the first computers, it had no documentation, so she wrote “A Manual of Operation for the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator,” which was perhaps the first computer programming manual. She or someone from her team once fixed the malfunctioning Mark I by discovering and removing a moth from its relays; the person taped the moth in the Mark I’s logbook, and noted “First actual case of bug being found”; Hopper subsequently popularized the term ‘debugging’ for fixing computer issues.

After the war, Lt. Hopper continued in the Naval Reserve, and in 1949, moved from Harvard to the Eckart-Mauchly Computer Corp. to help develop their UNIVAC computers, which had to be programmed by writing machine-level codes. She and statistician Max Woodbury developed the program that let UNIVAC correctly predict Eisenhower’s upset win surprisingly early in the 1952 presidential election.

Realizing the limitations of machine-level programming, Lt. Hopper proposed the development of a more user-friendly programming language using English words, but was told this couldn’t be done. Undeterred, she spent the early 1950s devising the MATH-MATIC and FLOW-MATIC languages, and developing ‘compilers’ to translate programs written in them into the machine’s language. In the 1960s, her ideas ultimately led to the development of the COmmon Business-Oriented Language (COBOL), a language that let programmers write human-readable instructions like ‘Add overtime to pay.’

Programs written in such ‘high level’ programming languages were portable between different computers, but this portability was threatened when companies began creating proprietary language dialects. To ensure portability, Hopper spearheaded the effort to create programming language standards and tests, a task that is today performed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

In 1966, Hopper was 60; she retired from the Naval Reserve with the rank of commander, but was recalled to duty in 1967 to direct the Navy’s Programming Languages Group. She retired again in 1971 but was again recalled to duty in 1972. At the time, centralized mainframe computers were the dominant computing paradigm, but she recognized the strategic potential of networks of minicomputers and began advocating to decentralize the Department of Defense’s computing systems. In 1970, she reached the mandatory retirement age of 64, but continued to serve by special Congressional approval. She was promoted to captain in 1973 and to commodore in 1983, a rank that was renamed rear admiral in 1985, making her one of the few female admirals. In 1986, Admiral Hopper retired from the Navy for the last time at age 79 as its oldest active duty commissioned officer.

But she wasn’t finished yet: that same year, Digital Equipment Corp. (DEC) hired her as a consulting engineer, a position she held until her death. This role included serving on technical committees, representing DEC at industry functions, and being a good-will ambassador. The role suited her well because she was a gifted speaker, able to communicate equally well with technologists, military officers, business people, young people, and the general public. She lectured widely about the history of computing, her career, and the need to build user-friendly systems. She loved teaching, and frequently remarked that her greatest accomplishment was the number of young people she had trained over the years.

In addition to her military promotions, Rear Admiral Hopper received many awards and honors during her lifetime, including the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, Navy Meritorious Service Medal, the Legion of Merit, the National Medal of Technology, 40 honorary degrees from universities world-wide, and numerous other honors.

Grace Murray Hopper spent much of her life battling the “We’ve always done it this way” mindset. To remind herself to think outside the box, she kept a ‘backwards clock’ on her wall whose numerals and clockwork ran counter-clockwise. She had a habit of bucking convention and espoused the motto, “It’s always easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.”

If you visit Washington D.C., I encourage you to visit the final resting place of this remarkable person, remember her many accomplishments, and celebrate her legacy.

Joel C. Adams is an emeritus professor of computer science at Calvin University.

Submit an Article to CACM

CACM welcomes unsolicited submissions on topics of relevance and value to the computing community.

You Just Read