Spectres in the Seventh Month (original) (raw)

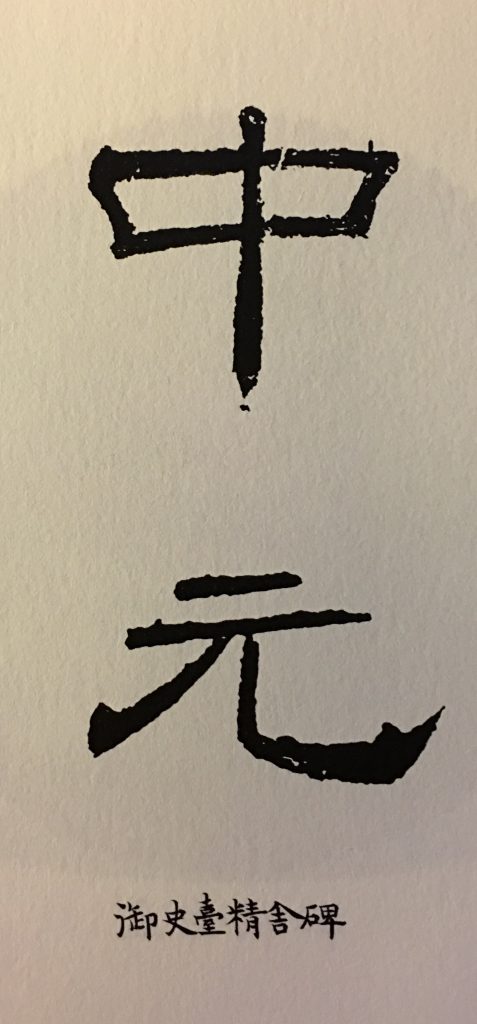

The Fifteenth Day of the Seventh Lunar Month 七月十五 is called variously Zhongyuan 中元節, Half Month 七月半 and Ullambana (उल्लम्बन; 盂蘭盆節, or simply 盂蘭節). It is a juncture during which elements of Taoist and Buddhist belief mix, both for the salve of the quick and the uplift of the dead.

This day is also popularly known as Ghost Festival 鬼節 for it marks the end of a two-week period during which the spirits of the departed, the recently dead, as well as ancestors, are freed by the King of Hell 閻羅王 who orders the opening of the Gates of the Nether World 鬼門關 so they can return to the realm of the living to receive succour and await further judgement.

The Seventh Month is also known as Ghost Month 鬼月, but it is particularly during the All Souls fortnight that the divide between the living and the dead is said to be more porous than usual. The living recall their loved ones, and make offerings to them to ease their existence in the afterlife, as well as propitiate the malign influences that are set abroad, so as to ward off evil.

***

Zhongyuan (Fifteenth Day of the Seventh Month), from calligraphy dated 724CE. Source: Stele of the Censor in the Temple 御史臺精舍碑, from 5 September 2017, Palace Museum Calendar 故宮日曆.

This is latest in our series of New Sinology Jottings 後漢學劄記. In it we commemorate the Festival of the Ghosts through an overview of literature, art, film and politics.

These Jottings are written in the spirit of New Sinology, encouraging an understanding of the Chinese world that does not artificially sequester an appreciation of culture, thought and religion from an understanding of politics, society and economics. It is a form of Sinology that has evolved during the present era of reinvented Chinese traditions; it is an approach that constantly recalls the diverse strains of history and culture that underpin the multiverse of China, a polyphonous world that the party-state of the People’s Republic attempts to dominate, silence, corral or eliminate.

New Sinology Jottings are not some kind of self-indulgent chinoiserie or post-imperial gewgaw. Their aim is not to provide readers with a light dusting of China literacy. Rather they take China past and China present seriously as they help readers appreciate, in a modest fashion, the skein of influences, ideas and traditions that continue to enliven the Chinese world. We hope also that these ruminations on China’s tradition of wen shi zhe 文史哲 (literature-history-thought) resonate with the reader’s understanding of other global cultures.

***

The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology is situated north of Wairarapa Moana, the lake after which the district is named. The Chinese name of the Academy is 白水書院, 白水, ‘white water’, being a translation of wairarapa, te Reo Maōri for ‘glistening waters’. In adopting this Chinese name we were mindful of the history of Baishui county in Shanxi province 陝西省白水縣. According to legend Baishui is the birthplace of Cang Jie 倉頡, a figure famous for having invented the Chinese writing system (倉頡造字). The advent of writing was said to have been such a momentous event — one that bought both weal and bane to the world — that ‘millet rained from the heavens and ghosts wailed at night’ 天雨粟 鬼夜哭.

The artist Xu Bing’s 徐冰 Ghosts Pounding the Wall 鬼打墙 reminds viewers of the ghosts wailing in the darkness, deprived of their easy manipulation of humanity by Cang Jie’s invention of writing. The title of the work — a collective rubbing made at the Great Wall outside Beijing in 1990 — refers to the folk idiom gui da qiang 鬼打牆: a wall 牆 built 打 by a ghost 鬼 to entrap travellers at night. These devilish devices so confounded travellers that no matter how hard people tried to escape they found themselves doomed to run in circles, caught forever in the invisible confines of the ghost’s wall. This is an appropriate analogy for our own meditation on Ghost Festival; it also captures the spirit of the nocturnal wailings of many of the writers and artists we introduce below. (On Xu Bing’s work, see Wu Hung, A Ghost Rebellion, Public Culture, 1994:6.)

Xu Bing’s Ghosts Pounding the Wall.

***

My thanks to John Minford for permission to quote material from his translation of Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio and his anthology of classical Chinese literature. Lois Conner kindly provided me with a photograph she made at the City of Ghosts, Fengdu 酆都, on the Yangtze River, and Gloria Davies suggested two excerpts from her book Lu Xun’s Revolution: writing in a time of violence. Annie Ren helped with Chapter 102 of The Story of the Stone and Callum Smith, the designer of the Heritage sites, set up the mini-anthology on ghosts. I am particularly grateful to Christopher Rea, whose work has previously featured in China Heritage (see 幽默: You Having a Laugh?), for acting as our guide to the spectral realm of China.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Fifteenth Day of the Seventh Month of the

Dingyou Year of the Rooster 2017

4 September 2017

丁酉雞年七月十五日中元鬼節

Pounding on a Tub and Singing 鼓盆而歌

Zhuangzi’s wife died. When Huizi went to convey his condolences, he found Zhuangzi sitting with his legs sprawled out, pounding on a tub and singing. ‘You lived with her, she brought up your children and grew old,’ said Hui Tzu. ‘It should be enough simply not to weep at her death. But pounding on a tub and singing — this is going too far, isn’t it?’ 莊子妻死,惠子吊之,莊子則方箕踞鼓盆而歌。惠子曰:與人居,長子老身,死不哭亦足矣,又鼓盆而歌,不亦甚乎。

Zhuangzi said, ‘You’re wrong. When she first died, do you think I didn’t grieve like anyone else? But I looked back to her beginning and the time before she was born. Not only the time before she was born, but the time before she had a body. Not only the time before she had a body, but the time before she had a spirit. In the midst of the jumble of wonder and mystery a change took place and she had a spirit. Another change and she had a body. Another change and she was born. Now there’s been another change and she’s dead. It’s just like the progression of the four seasons, spring, summer, fall, winter. 莊子曰:不然。是其始死也,我獨何能無概然。察其始而本無生,非徒無生也而本無形,非徒無形也而本無氣。雜乎芒芴之間,變而有氣,氣變而有形,形變而有生,今又變而之死,是相與為春秋冬夏四時行也。

‘Now she’s going to lie down peacefully in a vast room. If I were to follow after her bawling and sobbing, it would show that I don’t understand anything about fate. So I stopped.’ 人且偃然寢於巨室,而我噭噭然隨而哭之,自以為不通乎命,故止也。

***

In the following mini-anthology we include work from some of China’s most famous collections of ghost stories and strange tales, a comic episode from The Story of the Stone, reflections on death, ghosts and revenge by Lu Xun, samples of Cultural Revolution-era invective, a meditation on burnt offerings to the dead, two of the most powerful poems in Chinese on death and the afterlife, and a few observations on the Chinese Way of Death from a Beijing undertaker.

We also append a vocabulary list for those interested in how ghosts/ gui speak through Chinese.

— The Editor

People may treasure The Dream of the Red Chamber in their hearts, but they live in the world of The Water Margin; they might yearn for friendships like the Brotherhood of the Peach Garden in the Three Kingdoms, but they encounter the evil spirits and ghosts of Journey to the West. 人啊,長了顆紅樓夢的心,卻生活在水滸的世界,想交些三國里的桃園弟兄,卻總遇到些西遊記里的妖魔鬼怪。— popular saying

***

Contents

[To return to this Table of Contents from any of the following sections,

click on the ‘Back to Contents’ tab in the left-hand menu. _— Ed._]

- Weird Accounts 志怪

- Exorcism in the Garden 大觀園符水驅妖孽

- Sun Yat-sen’s Shades 革命尚未成功

- Lu Xun’s Ghosts 無常、女吊

- Mao Zedong’s Monsters and Demons 牛鬼蛇神

- Spooks in the Bamboo Grove 竹林魑魅魍魎

- Hong Kong Haunts 香港鬼打鬼

- Demons Demonise Demons 妖魔化妖魔

- P.K.’s Strange Tales 也斯聊齋

- Betwixt & Between 陰陽界

- Hymn to the Fallen 國殤

- Rhapsody for a Skeleton 髑髏賦

- A Wisp of Smoke 一溜煙兒

- Appendix I: Ghost Logorrhoea 鬼話連篇

- Appendix II: For the Dead Are Many 冤屈難伸

Fengdu 酆都, also known as the City of Ghosts 鬼城, on the Yangtze River. Photograph by Lois Conner.

Among the Monsters

The character for gui 鬼, from an oracle bone found at the Ruins of Yin dating from the Shang period 商 · 殷墟甲骨文.

In 1979, the People’s Republic of China was recovering from the three decades of the Maoist era. The extremism of those years had increased with what I call the High Maoism that was initiated by the Anti-Rightist Movement of 1957. That purge followed in the wake of the Hundred Flowers Movement of the previous year during which Mao Zedong had encouraged critics of the Communist Party and its rule over China to speak out, avowedly to ‘help the party rectify its work style’. Thinking that he was defusing the kinds of social and cultural tensions that had riven countries of the Eastern Bloc under the control of the Soviet Union, Mao was taken aback by the mass outpouring of grievances: widespread and pointed criticisms of Party dictatorship, corruption, mismanagement and brutish intrusions in everyday life.

Following Mao’s death, or what he had called his journey to ‘meet Marx’, the Communist rulers of the country turned away from the political narrowness which they themselves had instituted to focus on economic growth and the creation of a more normal, sustainable society. The policies of Maoism were being undone, if not reversed. The dead were, for the main part, acknowledged as victims of cruel injustice 冤枉 and commemorated. As for the survivors, many who had suffered years of exile, imprisonment or political stigma were given leave to speak out. Among the most outspoken, and popular, was the journalist Liu Binyan 劉賓雁.

In late 1979, Liu published a work of reportage about a corrupt Party official in the northeast of the country. In it he depicted a China that everyone knew about but one that the carefully controlled state media had kept out of the public eye. It was a tale of Party privilege, insider trading, corruption on a grand scale and details about the buying and selling of favours among the secretive cabal of cadres that had made the lives of so many for so long such a misery. Liu called his work People or Monsters 人妖之間_,_ a title that could also be translated as Among the Monsters.

Yao 妖 is one of those terms for spirit, wraith or creature from the nether regions. Often paired with jing 精 as yaojing 妖精, it was used in the overtly sexist attacks on Mao’s wife Jiang Qing following her detention with other members of the Shanghai clique in October 1976. Renyao 人妖 is also a pejorative term for transgender men, used in Singapore for the ‘Lady Boys’ who were a feature of prurient tourist interest for many years; it is also used as the Chinese translation of the Thai word katoey กะเทย, members of the Third Gender.

In China, the language of ghosts, malign spirits, devils and a general purpose Other (see ‘A Ghostly Guide’ below), has been used both traditionally and in the modern era, to identify threats, to belittle, demean and lampoon social phenomena and individuals who are regarded as being either on the wrong side of history, or outside the mainstream, as determined by whomsoever happen to be the power holders at the time. The modern Devil’s Dictionary of political vituperation has its roots in anti-Manchu rhetoric dating from the late-Ming period, vocabulary that was enriched and reinforced during the mid-nineteenth-century Taiping War and again by racist propagandists in the late Qing.

China is haunted. Not long after Liu Binyan’s People or Monsters — a work that was soon denounced and for which Liu was forced to make a secret, abject self-criticism — Sun Jingxuan 孫靜軒 published ‘A Spectre Prowls Our Land’ 一個幽靈在中國大地遊蕩. Imitating the famous opening line of the Communist Manifesto, Sun’s poem launched an indictment not only of Mao Zedong and his dictatorial ways, but of the grave pall cast over the country by two millennia of autocratic tradition: ‘Ancient China!,‘ Sun wrote, ‘A loathsome spectre/ Prowls the desolation of your land…’

This spectre decrees death,

posthumous humiliation,

Or tolerates lives of vexatious vegetation.

You are, then, spectral slave and spectral subject,

Without the right to cry out in protest.

— Seeds of Fire: Chinese voices of conscience, 1986.

A Country Haunted

The ghosts and spectres of the past preyed on the minds of China’s leading thinkers, writers and politicians throughout the twentieth century, as they continue to do so now in the twenty-first century. Some of the earliest fiction that appeared in the New Culture Movement (1917-1927) as part of the push for vernacular literature featured ghosts. As Christopher Rea notes:

In scholarly circles it has already become something of a cliché to say that modern Chinese literature is haunted. But Lu Xun’s most famous literary creation [_The True Story of Ah Q_] is a living ghost in multiple senses. Ah Q is an inhabitant of the Tutelary God Temple, the abode of spirits, and his appellation Quei is a homonym for gui. A dead man walking, Ah Q stands for buried cultural norms. As a fictional creation, he possesses zombielike immortality as a spectre that haunts those who would seek to vanquish Ah Q-ism once and for all.

— Christopher Rea, The Age of Irreverence:

A New History of Laughter in China, 2015, p.103.

***

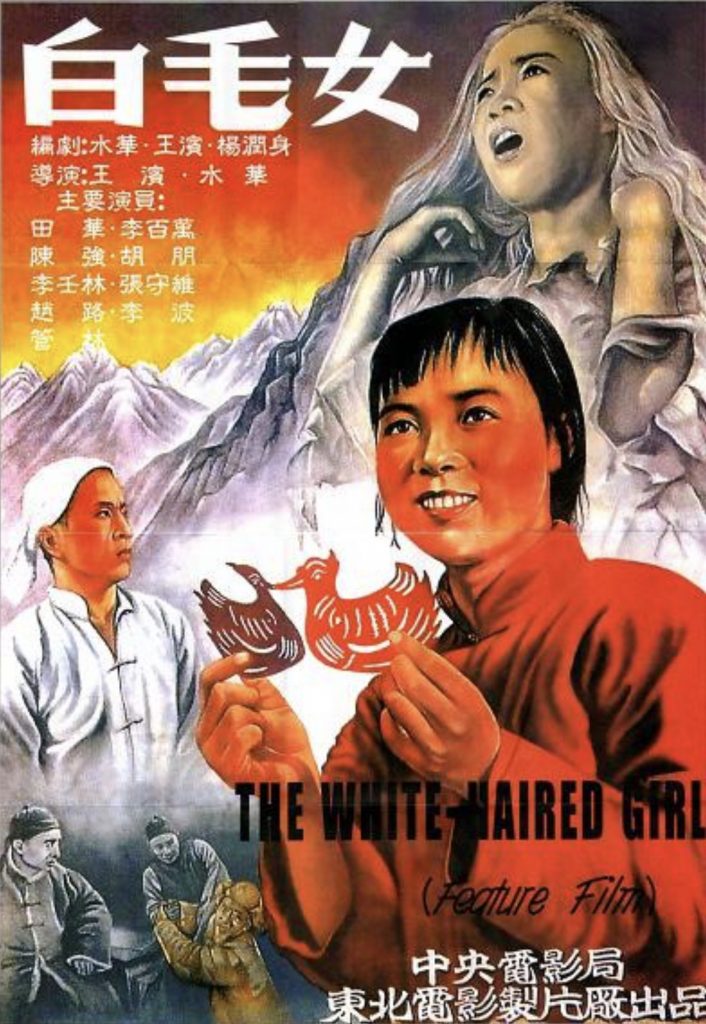

The Old Society forced People to become Ghosts;

the New Society transforms Ghosts into Human Beings

舊社會把人變成鬼,

新社會把鬼變成人。

This is one of the most famous lines in the old Communist opera The White-haired Girl 白毛女, which is still a set piece in China’s red cultural repertoire today. The grotesque irony of the sentiment expressed here, however, is lost on none. After all, the misconceived policies pursued by the People’s Government during the Maoist era from 1949 to 1979 resulted in industrial-scale state murder, something that left in its wake more ghosts than all the revolutionary wars previously fought in the name of creating a modern Chinese utopia.

Poster for the 1950 screen adaptation of The White-haired Girl.

As New China evolved in the 1950s, the Communist Party created what for all intents and purposes is a vast ghostly necropolis in the heart of its capital. Tiananmen Square was conceived of not only as a Chinese Red Square, a venue for mass demonstrations and the display of party-state might, but also as hallowed ground for the countless war dead, people’s heroes and revolutionary martyrs who are commemorated by the obelisk that pierces its centre. The friezes around the base of the obelisk depict the anonymous, stylised ghosts of revolutions past. In 1977, this symbolic necropolis was added to by construction of a mausoleum to house Mao Zedong’s embalmed corpse and his spirit still officiates over the square, his portrait hanging on Tiananmen Gate like that of an ancestor. The buildings flanking the Square itself mimic those just to the north — the museum to the Chinese revolution on the east shadows the dynastic-era Ancestral Temple 太廟 (renamed the Worker’s Cultural Palace), while the Great Hall of the People is paired with the Altar of Grain and State 社稷壇, now Sun Yat-sen Park.

The shades of the dead stretch over the history of the People’s Republic. The cultural historian Wang Yi 王毅 has argued that Mao was not only mindful of the spirits of the past, but also the ghosts and spirits surrounding him and the Chinese revolutionary cause. In the late 1950s, he was particularly concerned that people feared ghosts, real and imaginary, so much so that he instructed that a book titled Stories About Not Being Afraid of Ghosts 不怕鬼的故事 be produced (see ‘Song Dingbo Sells a Ghost’ in Searching for Spirits 搜神記). Wang goes on to argue, quoting the Chairman’s late 1950s speeches and comments, that the ideas motivating Mao’s attacks on ghosts and demons led to the further dehumanisation of his enemies, a process that would have dire consequences in the 1960s.

Mao was right to be obsessed, for he and his fellow Party leaders, pursued deadly policies that unleashed some of the darkest aspects of human nature, while in the process causing incalculable human suffering. Attacks on imperialists as ghosts, on the Tibetan rebels as devils, on the Taiwan separatists as ghouls were added to by Mao’s denunciation of traditional culture, including popular theatre works based on tales of ghosts 鬼戲. Then, in the 1960s, he and his theoreticians, including such figures as Zhang Chunqiao 張春橋 and Chen Boda 陳伯達, would identify remnant bourgeois elements in both the wider society and the Party itself as ‘Ox Spirits and Snake Demons’ 牛鬼蛇神. The creatures had to be uncovered, denounced and obliterated (see Mao Zedong’s Monsters and Demons 牛鬼蛇神).

The Cultural Revolution was unleashed to destroy Demons and Monsters, while in the process wiping out what were called The Four Olds. It was a national ruction that furthered the wrongs of the past and served only to lead to greater human misery. China remains haunted by the ghosts of the Maoist years, and works like Yang Jisheng’s Tombstone and Lao Gui’s Bloody Sunset are part of a library of histories and memoirs that reflect only in part the story of the three decades in which Mao and the Communist Party unleashed the forces of hell.

…Haunting the World

The kinds of haunting experienced in China, both in the twentieth century, and today, are hardly unique to that country. Nations, societies, ethnic groups and peoples struggle constantly with the legacies of the past. Political power-holders, those with a public voice, as well as religious groups, sects and associations of all kinds, not to mention individuals, can, when dealing with the shades of history, make things harder to discern by muddying the waters; a way ahead becomes thereby more difficult to navigate.

In this the second decade of the twenty-first century the party-state of China is only one political environment that is bedevilled by its legacies, by those things that it is prepared to acknowledge and use to its benefit, as well as by what it chooses to ignore or wilfully silence. There is an acknowledged wave of authoritarianism sweeping through Europe, the Middle East, Asia and the Americas. Post-communist revanchism has become a commonplace in countries like Poland, Hungary and Russia; Turkey’s autocrat uses religious belief and the ballot box to shore up his illiberal democracy, as do fundamentalist leaders in India. The Zeitgeist, literally ‘The Spirit of the Time’, is one crowded with unquiet ghosts. It is a spirit that calls to mind ghastly visions of the 1930s and other dark times. As the novelist John le Carré recently noted: ‘these are absolutely comparable signs of the rise of fascism and it’s contagious, it’s infectious. Fascism is up and running in Poland and Hungary. There’s an encouragement about.’

Le Carré also notes that in the United States Donald Trump’s use of ‘fake’ undermines the credibility of everything — the news, politics, opinion and the law. This has global ramifications. Today the spectre that Sun Jingxuan wrote about in the early 1980s casts a pall over the world. The China Dream 中國夢, the China Formula 中國方案, the China Way 中國道路 — or more simply put: globalised state capitalism married to harsh one-party rule — can now have a fearsome impact. The unrequited spirits of China’s past haunt us all, and it is alarming to realise that those wraiths find fellowship wherever they go.

New Ghosts

On June Fourth 1989, the vast public space of Tiananmen Square became a different kind of symbolic graveyard, one for the aspirations of many who sought a society that enjoyed greater freedom, openness and democracy than that allowed by the Communists since 1949. We previously commemorated that date in the essay The Gate of Darkness on 4 June 2017, quoting a poem by the Hong Kong writer Xi Xi:

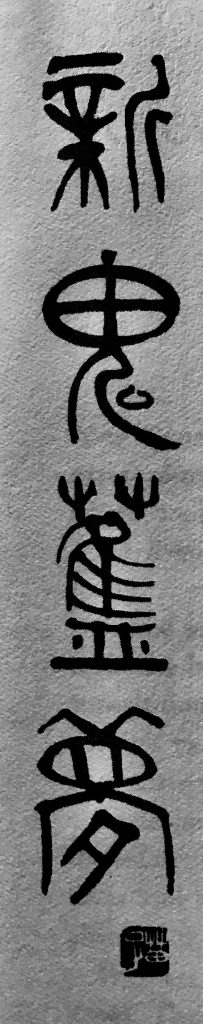

‘New Ghosts, Old Dreams’ 新鬼舊夢 in the hand of Huang Miaozi 黃苗子.

We hear the sound

Of your weeping.

Mother, I beg you

Not to look for us again in the square,

The wasteland, where

Crushed tents, banners, command posts,

Public address stations

Strew the ground.

Teachers, students, friends

Are all gone.

The acrid smoke of gunfire

Fades as

Thousands of lives

Turn to ash. …

We hear the sound

Of your weeping.

We fell together,

Together we rise,

Joining once more our parted hands,

Holding our torches even higher.

A wound gapes

On one man’s chest;

A tank tread

Furrows one man’s brow.

But these wounds lie

On the body’s husk;

We are beautiful beyond compare.

Nothing can hurt us now.

We will share

The city’s splendour

With the stone beasts —

They, on their columns,

We, on the People’s Monument —

Calling

Across the square.

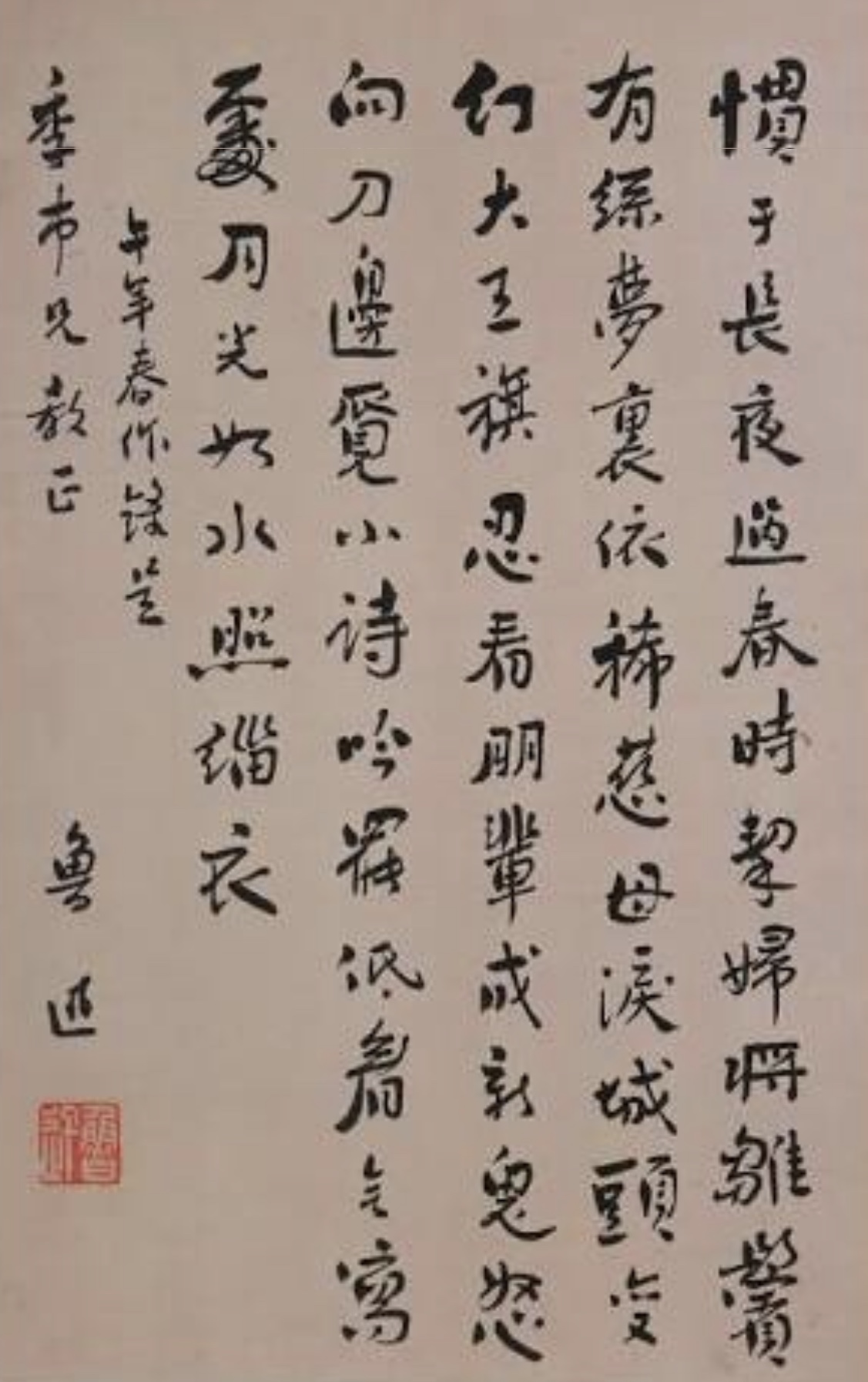

Xi Xi’s poem first appeared in New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese rebel voices, a book conceived by John Minford with me as a sequel to our 1986 Seeds of Fire: Chinese voices of conscience. We were responding to the events of 1989, and we took our title from a famous poem by Lu Xun, composed after he heard of the execution of five young writers in 1931. He mourned those killed as ‘new ghosts’:

I can but stand by,

looking on as friends become new ghosts,

I seek an angry poem

from among the swords.

Lu Xun’s 1931 poem, ‘Untitled’ 無題.

Illness forced John to set aside work on New Ghosts, Old Dreams, but Linda Jaivin joined me to work on the book, which was published in 1992.

In China Heritage we frequently return to the collections Trees on the Mountain, Seeds of Fire, New Ghosts, Old Dreams, Shades of Mao, as well as the translations made over the years by John Minford and others. These are not mere spectres, or just the ghosts of ideas, people or hopes. They are works that contain part of the heritage that we continue to promote and to which we will, through our present endeavours, add over time. In various ways we dwell on this accumulated legacy and savour it still in these virtual pages.

***

In November 2015, a revived stage version of White-haired Girl, under the artistic direction of China’s First Lady, the songstress Peng Liyuan 彭麗媛, began a season with a première in the old communist base city of Yan’an, Shaanxi province, seventy years after its first performance in 1945. Under Xi Jinping the People’s Republic continues the Maoist heritage by turning those who dare to oppose it into new ghosts.

A Ghostly Guide

The literary historian, humour specialist and translator Christopher Rea adroitly guides us into China’s world of spectres. As he notes:

Like the English word ghost, gui 鬼refers to the spirit (or spirits) of the deceased, which may assume various forms and be malicious or benign. Chinese ghosts haunt the human realm because of some unresolved grievance, withdrawing to the netherworld (or being elevated to heaven) only after they find justice. Like ghosts in other folklores, they inhabit a liminal space in both existential and psychological-emotional senses. As paranormal beings, ghosts are simultaneously present and absent; as symbols, they represent human memory and longing.

Encounters between ghosts and humans is the subject of a vast literature of the fantastic, including the famous Qing dynasty literati story collections Strange Tales from the Liao Studio 聊齋誌異 (ca. late seventeenth to the early eighteenth century [translated by John Minford as Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio) and What Confucius Didn’t Talk About 子不語 (1788). In these stories, ghosts appear in various guises, from seductive and vitality-sucking fox fairies to vengeful wraiths and bumbling dupes. Though supernatural and often frightening, gui are as fallible as human beings and, being bereft of life, ultimately more pitiable. What Confucius Didn’t Talk About, complied by the poet and scholar-official Yuan Mei 袁枚, takes its title from the Confucian injunction against concerning oneself with anything but the social, ethical, and moral problems of the mortal realm: ‘Respect ghosts and divinities, but keep them at a distance’ 敬鬼神而遠之.

As Rea comments on the usage of the term ‘ghost/ devil’:

Gui also has a long history as a popular curse. A first century CE dictionary notes that gui has a yin (female) aura that is ‘harmful and goes against the public good.’ While it has signified that which is foreign or distant, literary historian Judith Zeitlin observes that ‘over the centuries it acquired an array of extended meanings, including “cunning” (in the sense of both crafty and well crafted); “covert,” “stealthy”; “unfathomable,” “mysterious”; and “nonsensical.” ’

The 1800s saw the beginning of a cultural shift from interest in ghosts as supernatural phenomena to their usefulness as a political symbol. When Which Classic? 何典 was written at the turn of the nineteenth century, gui was already in widespread use both in China and abroad to brand people as ‘non-Chinese”, marking them as people of unfamiliar cultural practices, if not ‘beyond the pale of civilization.’ A few decades later, China was dealt a crushing blow to its self-esteem by the ‘foreign devils’ (yang guizi 洋鬼子) who routed Qing forces during the Opium Wars of 1839-42 and 1856-60. The foreign trade in opium led to the appearance of the ‘opium fiend’ (yangui 煙鬼), an object of lament, revilement, and fascination in literary and pictorial representations of China. By the 1870s, when Which Classic? was first published, Chinese society also had ‘fake foreign devils’ (jia yangguizi 假洋鬼子) — Chinese seen to be mimicking foreigners in their dress, speech, and behaviour. By 1921, Lu Xun mocked the widespread and indiscriminate use of the curse ‘fake foreign devil’ by putting it in the mouth of Ah Q.

When referring to an actual ghost, gui usually denotes an Other, a deceased stranger rather than deceased kin. As an epithet, however, gui implies familiarity. Just as parents might affectionately refer to their children as ‘little devils’ (xiaogui 小鬼), people who apply the term gui to others (be they Chinese or non-Chinese) peg them to what historian Adam McKeown calls a ‘habitual stereotype.’ A ‘little devil’ is persistently mischievous, a ‘foreign devil’ is always culturally distant, a ‘drunk devil’ 醉鬼 is perpetually alcoholic, and a ‘wretched devil’ 窮鬼 is forever impoverished. Whether used as a term of revilement or endearment, gui denotes a way of being or set of behaviours that is predictable.

— Christopher Rea, The Age of Irreverence:

A New History of Laughter in China, 2015, pp.88-89,

with slight modification and the addition of Chinese characters.

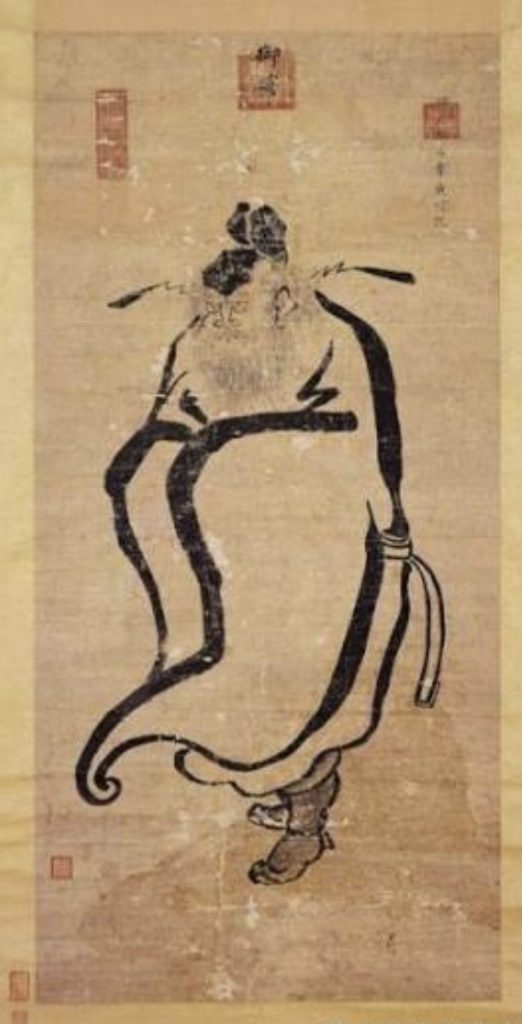

Zhong Kui 鍾馗, the devil-chaser, said to have been painted by Shizu 世祖, the Shunzhi emperor 順治, 愛新覺羅·福臨 in 1665. Source: Taipei National Museum.

In the following mini-anthology we include work from some of China’s most famous collections of ghost stories and strange tales, a comic episode from The Story of the Stone, reflections on death, ghosts and revenge by Lu Xun, samples of Cultural Revolution-era invective, a meditation on burnt offerings to the dead, two of the most powerful poems in Chinese on death and the afterlife, and a few observations on the Chinese Way of Death from a Beijing undertaker.

We also append a vocabulary list for those interested in how ghosts/ gui speak through Chinese.

— The Editor

Spectres in the Seventh Month

Contents

[To return to this Table of Contents from any of the following sections,

click on the ‘Back to Contents’ tab in the left-hand menu. _— Ed._]

- Weird Accounts 志怪

- Exorcism in the Garden 大觀園符水驅妖孽

- Sun Yat-sen’s Shades 革命尚未成功

- Lu Xun’s Ghosts 無常、女吊

- Mao Zedong’s Monsters and Demons 牛鬼蛇神

- Spooks in the Bamboo Grove 竹林魑魅魍魎

- Hong Kong Haunts 香港鬼打鬼

- Demons Demonise Demons 妖魔化妖魔

- P.K.’s Strange Tales 也斯聊齋

- Betwixt & Between 陰陽界

- Hymn to the Fallen 國殤

- Rhapsody for a Skeleton 髑髏賦

- A Wisp of Smoke 一溜煙兒

- Appendix I: Ghost Logorrhoea 鬼話連篇

- Appendix II: For the Dead Are Many 冤屈難伸

My day is done. I go because I must:

Silence will be my way of saying so.

— from Clive James, ‘Quiet Passenger’