Women's Voices from the Starry Family Correspondence - UM Clements Library (original) (raw)

As one of the Clements Library’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) interns, I was tasked with conserving and providing descriptions of manuscript collections that feature historically underrepresented perspectives and subject matter. The collections selected for the DEI projects were high priorities because of their need for conservation and for descriptive cataloging. As a result of the manuscripts’ damaged states, many were unreadable and inaccessible to researchers, students, and faculty.

One of the three collections I worked on was the correspondence of James H. Starry and his family. The James H. Starry Family Correspondence is a collection of 36 items, 35 of which are letters, containing personal accounts and discussions about local happenings, marriages, and religion between James H. Starry and his various friends and relatives. In many of the letters, James wrote from Charlestown, Virginia (now West Virginia) where he lived with his parents, and in others he wrote from Clarksville, Ohio, where he lived with his wife. James worked as a farmer; his brother, John, worked as a physician; and his brother, Joseph, was a sheriff, jailer, and landowner. Among the less common topics discussed in the letters are women petitioning for divorce, men and women discussing the activities of slaves, and temperance and drinking. Particularly notable are candid writings about and between women.

For me, it was incredibly fascinating to hear the women’s voices through their own writing, for it provided an at times unfiltered glimpse at some of their ideas, perspectives, and experiences during specifics moments in time. The narratives of women vary from discussions of marriage and motherhood to remarks on abuse and violence, making this collection particularly valuable for the study of women and gender relations.

The Starry family correspondence has four prominent female writers: Caroline, James’s cousin in Shepherdstown, Virginia; Sally, James’s sister in Charlestown, Virginia; Nancy, James’s wife in Clarksville, Ohio; and Anna Kelly, James’s mother-in-law in Clarksville, Ohio. Each woman had a distinct writing style and relationship to James. Caroline was the most confident and forward in her writing. She was comical, witty, intelligent, and biting, utilizing phrases such as “choke me black” and referring to her cousin’s fatness as “that kind of sweet potatoe.”

Sally corresponded regularly with her brother James and frequently acted as a mediator between him and their mother. She often relayed information and attempted to bribe him (literally, with money) into writing more frequently. Despite her apparent youth, she appeared to have a relatively elevated command of the English language.

Nancy, James’s wife, had a lower level of literacy and her letters contain many phonetic spelling variations. Consequently, Nancy’s letters are especially valuable for the way they reflect her spoken language and dialect. The relationship of Nancy and James varied from concerned and loving to manipulative and abusive. During the 1840s, James spent much of his time living with his parents and siblings in Virginia while his wife and children lived in Clarksville, Ohio. James was seven or eight years older than Nancy and often treated her in a condescending and child-like fashion. He frequently criticized her parenting, despite being an absent father himself, and often told her how much she should love him. Reading their letters over 170 years later, I had a difficult time reconciling their brief moments of love and flirtation with James’s manipulation and neglect. On rare occasions, Nancy would directly express her frustrations with James’s unfulfilled promises to return home. On April 24, 1848, for example, after Nancy expressed her continued frustration and disappointment with James, she wrote “I doant want you to disappoin me again or when you doe com home I will pound you.”

Perhaps the most interesting exchange between James and a female writer occurred when his mother-in-law Anna Kelly (or, Kelley) sent him an update on January 30, 1848. The letter begins very typically, as Anna informed him of recent local news, and apologized for her grammatical mistakes. Before she concluded her letter, she included a troubling story in which an older local man took a young girl to a tavern to room for the night, seemingly against her will. Anna wrote:

“old solsbery has bin cuting up he has took up with a girl that he raised but tha have got the old chap and are going to try him for his good be havier he took the girl and started of with hur and went to butlervill and stoped at the tavern and caled for a room that had low beads in and told the lanlord that he had a young womin with him and that she was very timed and would like to have hur in the same room with him the lanlords gerls lighted hur to bed then she told the girls that she wanted the key to lock the room her self then old sol went up to bed the lanlords gerls looked in at the key hole and saw hem in bed with hur tha went down and told their father that tha was in bed to gether the old man went up and told them to leav his house tha got up and went to the mouth of the fork it was a bout ten oclock.”

|

|---|

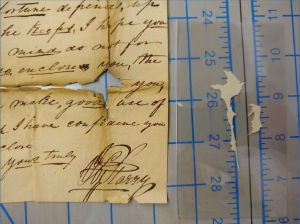

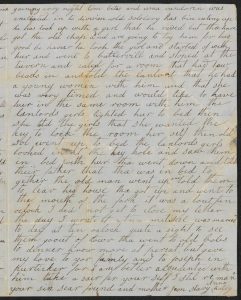

| Anna Kelly’s letter to her son-in-law James H. Starry, January 30, 1848, in which she relates news about “old solsbery” and a young woman at a tavern in Butlerville, Ohio. |

While it is empowering to see the tavern keeper’s young daughters advocating for the poor girl trapped in the room with this older man, it is disheartening to think of what may have happened to her before or after they left the Tavern. Furthermore, it is unfortunate that we do not have any more information or historical records that would be able to provide even a cursory look at the life of this woman.

The Starry family correspondence suggests the resilience and strength of young mothers, witty cousins, and loyal sisters, and also the manner in which women stuck together in order to help one another. These women’s letters highlight their everyday and unglamorous struggles in the rural America of the 1850s during a time when they relied primarily on each other for encouragement, support, and appreciation. The conservation work and finding aid description resulting from my DEI internship will allow faculty, students, and other scholars to discover, access, and utilize the Starry correspondence for their research.

– Ella Horwedel

Student Intern