“A War on Poor People”: Speaking Out Against Drug Criminalization (original) (raw)

Moses’ Life Mapped

Move the map around to see more points of interest and click on dots or regions to see some information from Moses’ interview.

The boundaries in the map below are meant to show general regions, not precise boundaries.

Map by Haverford Digital Scholarship.

Instructions for Navigating the interview:

The site presents Moses’ own words on the left. When reading through the interview click on the underlined text to reveal multimedia commentary and background information on the themes Moses discusses. Doing this will enable you to gain a broader sense of the history and context that would otherwise remain implicit in Moses’ descriptions.

A Change in North Philadelphia

Moses: So in the ’60s, there was a push, it happened a couple times, there was a push for Puerto Rican people to move off the island… They offered jobs in New York, in Chicago, and I want to say New Jersey. There was two migrations[of Puerto Rican people], one to Spring Garden and then one to North Philadelphia. Actually, one to Spring Garden, one to South Street, because Puerto Ricans used to live on South Street.

The following image is an airline map of the United States and Puerto Rico displaying the major principal flights in 1965 (An early wave of Puerto Rican migration). As Moses’ family history illustrates, many Puerto Rican migrants travelled up through Florida and settled in Northeastern cities like New York or Philadelphia

(Rumsey)

Then they were pushed out in the early ’80s, and they went to North Philadelphia…. …. all of South Street. It was black and Puerto Rican people.

Spring Gardens, a location mentioned by Moses as a place in Philadelphia where many Puerto Ricans lived. This photo was taken in 1972 and found in: PhillyHistory.org

Paul: When you say North Philly, you’re talking about Kensington?

Moses: Kensington and Fairhill.

Paul: I’m always wondering, is that where you were allowed to live?

Moses: Basically…. … that was what they could afford. I don’t know if you guys know much about Philadelphia’s history and segregation. Philadelphia’s always been super segregated, they would keep pockets of people like the Italians, they would keep them in South Philly….That time in Kensington, it was a little funny, because it was the mid ’80s like I said earlier, it was still Irish. Poor Irish and poor Polish still living in that area in Kensington. They were poor, but they were better off than the Puerto Ricans that had just moved into the neighborhood, because the Puerto Ricans were really, really poor when they moved into that section of the city…. … We used to run around the streets, play until the sun went down, lights came on.

But there was a little bit of tension there, because we were gentrifying the neighborhoods, and once the Polish and the Irish left, all the resources that were in the schools, the streets, everything dried up. Then you started seeing heroin coming to the neighborhood.

Paul : Is this like 1987, like heroin?

Moses: 1987. Before that, heroin was around, but people were in their houses. There weren’t needles on the streets. The most you’d find is like the caps to the syringes, and we knew not to touch them… Kids didn’t have to be afraid to go outside, could have fun, play until whenever. After heroin was introduced into the neighborhood, things got a little worse, but everybody still had jobs. Everybody still had their homes. The cops hadn’t yet started arresting people for being heroin users.

This graph reveals the policing changes Moses’ neighborhood has undergone by illustrating the disproportionately high incarceration rates of Northern Philadelphia. It supports his anecdotal testimony that policing of heroin use increased during the War on Drugs. Source: Pew Research Center

Back then, the neighborhood was pretty good. We had crime, there was drugs, but usually on the blocks we had about four or five houses through your family, all Puerto Rican neighborhoods. So there was about, I know on Somerset there was like six families that were on the block, but they were in multiple houses… … and everybody called each other cousin**,** because we all grew up on the same block.

Even then, this was like late ’80s going into the ’90s, there was drugs, everybody knew there was drugs, everybody knew who was using heroin, but those were your neighbors. So you saw them, “Hey, how are you doing?” You give them the respect, the greeting of the day with respect….. The community was pretty tightly knit until I left to the Army. I left in 1999 and came back to a different story… So 2013, I came back. In 2013, I couldn’t even believe what I was seeing, because things have gotten so bad in the 7th District, Fairhill and Kensington.

People were getting killed every day, there was the encampments had just started up. But what I had noticed, in the beginning I was like, “I don’t understand why these people can’t get their lives together, just like anybody else in Philadelphia. What is going on that they’re not? They must not be doing something right to help themselves.” Until I found out that it was a lack of resources. There’s a lack of resources starting from the schools that the kids go to, to when they’re adults. The only resources they have is maybe welfare, being on welfare, and they’re sent into a program where they learn to be … Nurses assistant or medical assistant, or something that’s very menial that doesn’t push education. Like, “This is your job, it’s a good job. Deal with it.” So people are suffering from that as well in North Philadelphia.

Poverty in Philadelphia is widespread, but affects Northern Philadelphians at a disproportionate rate. In much of North Philadelphia, the poverty rate is over 45 percent, “while in most of the city’s residential zip codes, it is over 20 percent” (“The State of Philadelphians Living in Poverty, 2019.”).

Paul: What is the relationship to the way people treat drug use generally?

Moses: In the neighborhoods, I think it’s mainly that people forgot how to treat each other, number one. Number two, it’s a lack of resources. Because the way I look at it is like this, you have these kids out running around in the streets and stuff like that, usually their parents aren’t home. Or you have one parent that’s home, but it’s not for real, because they’re working a job or two, so the kids are doing whatever they want. Acting crazy, breaking things, beating up people, treating people wrong, because there’s nobody there to say, “Hey, don’t do that.”

It’s a breakdown in the family structure, a breakdown in the schools, and in just the lack of resources. In North Philadelphia, this is me speaking honestly, North Philadelphia the problem is that the leadership in North Philadelphia is about making money and not about the citizens.

The thing is that I love Philadelphia and I love the people from my neighborhood… People in North Philadelphia are always surviving. They have to survive, they have to survive the winters, because sometimes they don’t have heat. They have to survive the summers, because they don’t have air conditioning. They also have to survive the summers, because there’s a lot of shootings. There are so many things that put the brakes on people’s lives in North Philadelphia, you wouldn’t even believe it just if you actually really saw what’s going on for people in North Philadelphia.

You’re just getting a glimpse, you’re getting what’s on top. When you get to the root of it, it’s really, really systemic and it’s ingrained to them. People in North Philadelphia don’t believe that they can do more, that they deserve more. It’s like, “This is life. This is what it is.” Getting back to your question about the kids, how do I teach my kids differently? I tell them that there’s more, like go to college, study. I’m always on them about education. To me, then working, it’s not a big deal right now because they’re kids and they need education so that they can have generational wealth. That’s what I’m trying to give my kids right now. I want to get things so I can have land, so I can go, “Here, this is for you. This is for your sons when you have them, or your daughters.”

But we never had that. There was no wealth to be passed on from my grandparents, there was no wealth to be passed on from my parents. Right now, I’m trying to build something to pass onto my kids. That’s what, people in Philadelphia are all going through the same thing. There’s no generational wealth.

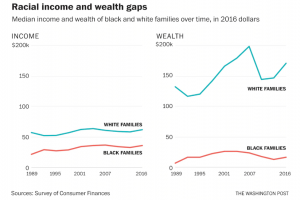

This image depicts the racial disparity in income across time, relating to Moses’ discussion of generational wealth. Source: The Washington Post

People smoked crack, but it wasn’t like … People smoked crack, but back in those days it was different. People that were using drugs were people in your family that lived on your block, so nobody was like, “Get out of here.”… … Most of these people were in North Philadelphia, they’re from the neighborhood. 98% of the people, they did a survey to see if people were from Philadelphia or they were from Bucks County. 98% of the people out there were from Philadelphia.

You can’t get drugs out there.

But the one thing is, those people, they’re from the neighborhoods. The ones that you see running around intense sometimes, maybe some of them aren’t, but most of the people that are out there using drugs have houses in Fairhill. So they’re just going to run back to their house. The ones that have lost their houses are sleeping under the street, I assume maybe some people that are coming from somewhere else are probably out there too. But most of those people are from Philadelphia. Maybe not from North Philadelphia, but they’re from Philadelphia.

How the War On Drugs Impacted Moses’ Family:

Moses’ First Experience with the Drug Epidemic

Moses: ….it was about 1988, 1989, my mom’s aunt, we went to see her, she lived two houses down from my grandmother, it’s my grandmother’s sister, she’s sweating profusely and she told my mom that she was going to die. She’s like, “Maybe I’m going to die tonight.” She didn’t want to go to the hospital, because she was afraid she was going to get arrested, and she had a son that had down syndrome. But she had shot up and I don’t know if it was a bad batch of heroin, later on that night she died. She died and my mom told me the next day. But that was my first experience with the drug epidemic. It hit our family hard, it hit both sides of my family.

The First Time Moses Saw a Relative Using Drugs

Moses: About the first time I ever saw anybody using was my Uncle Harold, he was shooting up heroin in my grandma’s basement after his wife left him for heroin, because he was using heroin. But I didn’t understand, I was about six years old.

Yeah, I was six or seven. I looked into the basement where we used to live, I was being a nosy little kid, I looked into the basement and I saw him put the needle in his arm. My grandma just so happen to come out at the same time from the house and asked if I saw my Uncle Harold. So me trying to protect my Uncle Harold, because I knew he was doing something that in my mind he wasn’t supposed to do, I told my grandma, “He’s downstairs putting a bandaid on his arm.” So my grandma freaked out, she’s like, “What?” Because I didn’t know, I was a little kid. So she goes down there, tears into him, he’s “I’m sorry. I got this disease.” … He was just saying, to Puerto Ricans, everything’s a disease… So he says, “I have a disease. I’m sick.” But this was prior to anybody saying drug addiction is a disease. In our family, growing up in an Afro-Puerto Rican family, we took care of our family members that were on drugs.

From Uncle Tadeo to His Grandson: Cross Generational Deaths

Moses: So just like my Uncle Tadeo just died. In fact, I’ve got a story to tell you about his grandson, to show you how this is generational, the impact. My Uncle Tadeo, a couple years ago, he was killed by one of my cousins in Florida. He was a heroin addict since he was 15 years old, he died when he was 42.

When he lived here in Philadelphia, at 15 he started using heroin. His kids in turn, his kids don’t use drugs, stay away from drugs, they still live in the same neighborhood as they did when their father was alive and they were born, on Swanson and Somerset. Last week, his grandson was killed…. … Kid was 18 years old and he suffered from generational, I call it generational trauma, because of the things that were happening in their neighborhood. Now there’s a bunch of other little kids left behind, my little cousin that just died, they range from the age of 16 all the way down to seven. Now all these kids are traumatized by the death of this older cousin…

But my Uncle Tadeo didn’t have any resources as a kid, he didn’t have any resources as an adult. The resource he had was getting put in jail and them making him go cold turkey, and he would come right back out and be good for about two weeks, and then get right back into the loop… … Incarcerated on and off from the time he was 15 until he died, he was 32.

Paul: Did he ever go to rehab?

Moses: He did. Funny story, my Uncle Marco… he has a rehab [center].

But he [Marco] was a heroin addict and he was a coke dealer. Someone set him up, shot him 38 times, he survived, turned his life around. Opened up a drug rehab, but it was faith based, so he had a lot of people that are forced to change while they were there. But then would leave and they would end up back in the same place two years down the road. My Uncle Tadeo went through my uncle’s drug rehab, and he was in and out of it until he died. So I’m not too big on faith based drug rehabs, because they don’t base it around mental health, they base it around faith.

….And I saw the world, came back, so my whole view on the world is totally different. I try to get these kids to see that, but when you’re stuck in a bubble … with Plato in the cave, that’s the type of life they live. They’re looking at a wall, that’s all they see, so they don’t know what’s behind them. So to me, it really hurt me because it was generational. His grandfather was killed, his father was a drug dealer, and he gets killed. It hurt me to the core, because I’m looking at this kid and he’s just a year older than my son. I’m telling my son, “Your cousin got killed.” My son’s looking at me like, “What are you talking about? What do you mean he got killed?”

This infographic depicts the Cycle of Disadvantage and shows the factors influencing the generational trauma Moses discusses. Source: “Breaking the Cycle of Disadvantage.”

So it hurts me because it’s my blood, but it also hurts me because it’s just a kid that didn’t get a chance to live. He had no chance at anything in the condition that he was in. When I say condition, I mean like his stance in the world or in society, he just didn’t stand a chance.

The School System’s Role in the Death of Moses’ Nephew

Moses discusses how schooling in neighborhoods that are highly segregated and have a relatively high rate of drug use Philadelphia contributes to an achievement gap both in school and later in life. This is further backed up in an article by Tegan Murphy which states, “…there are several issues today that keep the achievement gap in place… [m]odern day segregation in schools is one of these issues.” (Murphy)

Read more here: Understanding the Achievement Gap

Moses: …my nephew. He died, I don’t know if he was selling drugs, I think they were fighting over turf.

My kids, in fact, my kids just met this cousin[Moses’ nephew]like maybe a month ago, so they were pretty distraught about it. The way I feel, I’m hurt, because he was a kid. He just turned 18, had his whole life ahead of him, but at the same time, I feel like he was set up to fail. He was set up to fail. The schools that he went to, below any standard that you can imagine.

The school, on every corner of the school there’s pockets of drug dealers. All around the school there’s people using. They can’t use in their homes, because most of them are homeless. So they go into this neighborhood, this is right off of Cambria, they go into this neighborhood and there’s people there high on the corners, high on the streets, and the kids are going to school. But a lot of these people there is their family members. But the schools, they’re not where they need to be. To me, the schools in particular, if the schools are not doing well, the neighborhood’s not going to do well.

This affected them to the point where the only thing they know and the only thing they see is what’s in front of them. I’m just giving you the psychology of it all. What they see and what they have is all they’re going to ever have, so they’re going to fight for what they have tooth and nail, even if it means that they’re going to die. I didn’t even think about prohibition and what my cousin was fighting for that got him killed. But think about the way it hurt me, the reason it hurt me is because I knew that there was no other choice for him. A lot of these kids, there is no other choice for them.

Moses’ Father Joining the Police Force

Moses: So this one sergeant working in narcotics got into a fight with my father, my father was pretty new to the [police] force, he was on the force a year or two. Got into a fight with my father, they pulled them apart, the guy gets loose and beats up my mom. My mom, mind you, had a mouth full of braces. The next day, she had the whole inside of her mouth was cut open, she had bruises on her face, bruises all over her body. So two narcotics’ officers come to my house, tell my father, “We want to push this under the rug, what can we do? Because the sergeant was going to retire in a year, we don’t want to mess up his career.”

He was like, “No. We’re going to press charges.” So the narcotics’ officers put drugs in my dad’s car. Set him up. He almost won the case, but because he was broke and he’s black and he became poor, never got a job again. My father has been without work, legitimate work since 1996.

Ruined his life. I went to become a police officer a few years back, and my father’s information popped up… … I was like, “That’s my dad.” They were like, “You’ve got to go talk to this guy.” I had to go talk to Internal Affairs.

Paul: What happened?

Moses: I didn’t become a cop. But that’s the way it works. That’s another thing I want to fix.

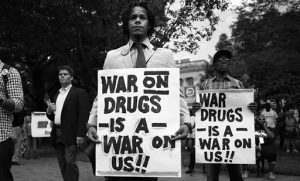

Paul: …if we get back to the war on drugs, what is the war on drugs?

Moses: A war on poor people. To me, that’s what it is. It’s a war on poor people. Because think about it, when a person that’s affluent is using drugs, Charlie Sheen for instance, did they put Charlie Sheen in jail? So our poor people that are literally using drugs, their drugs that they bought with their money in their homes or wherever, why are they getting pushed into prison? They’re demonized.

I remember thinking back in the Clinton years, I’m not that old, but I’m 38, but back in the Clinton years I was a teenager, and I remember Hillary Clinton talking about superpredators and how they needed to make them heal. That’s when the war on drugs got really extreme, and a lot of people started going to jail for petty reasons. They . . . you had three strikes, it’s a war, but mainly a war on people of color that are poor. I’d like to fight against that too.

Media Misconception of the “Badlands”

Crew 2: I would add to that too, there’s a zoning narrative that people surround about it, “Oh, it’s just the Badlands, the bad people, bad land, bad everything.” And how does that count …

Moses: In my reality, the Badlands, first off, people say Badlands, but they don’t really know what Badlands means. Badlands is the name of the area, because the land was bad and the houses were sinking.

The Badlands, if you go to the Boulevard, that’s actually where the Badlands is. There’s a whole set of billboards, but there’s no houses, because all the houses started sinking into the ground because of water, and they called it the Badlands and it just caught.

The media did it, so number one, the prices in the neighborhood for the houses dropped. The resources for all the schools dropped. The people stopped putting money into North Philadelphia, and once they started taking those resources, more people used drugs. You started having more people kill each other.

Screenshot taken by @Rittsqu and featured by an article in The Philadelphia Inquirer. It shows the area Google Maps labeled as “Philadelphia Badlands” in 2019.

Encampments

Paul: You can get lots of people, but they’re just like from Christian Street. People are like, “They’re not from the neighborhood.” It’s like, “They’re just from two miles away.”

Moses: The thing too, because it’s so close to the L, people come and get drugs and they jump right back on the L and they go home. So the numbers that we’re seeing aren’t the real numbers. We’re seeing a small percentage of the people that are actually addicted. I’ve seen everything.

Paul: … I saw an interaction out on the street here with somebody who was talking about how he went and did some video projects up there when they were moving out the encampment. Somebody came by, she was like a restaurant owner from Frankford Avenue, and she was just like, “Why would you do that? Those people are just trouble.” She honestly had no idea why anybody would support that idea. I’m just wondering what your thoughts and reaction is about all of that.

Moses : About people …

Paul : Like the encampment, the moving of the encampment, all of that.

This image, taken beside the Kensington Avenue underpass, shows one of the encampments in Kensington

(Jeffrey Stockbridge for The New York Times)

Moses : Me personally, I believe if the city’s going to move people out of the encampments, they have to have somewhere to take them. If you don’t have a shelter to put them in, if you don’t a warm bed for them, leave them alone. They’re not bothering anybody, they’re doing their little thing, they’re in a neighborhood. They’re not bothering anybody in the neighborhood. I know some people in the neighborhoods were complaining about people using the bathroom out on the streets and stuff like that, but if that’s the case, the city can put out porta potties and clean them up. There’s money for that. They can put out porta potties, they can put out things like hand sanitizer, things like that.

Moses: The reason they’re moving these encampments is because they want to make money. They’re trying to gentrify that part of the city. That’s the only reason Quinones is trying to move them. It’s sad, because they need help. But they don’t really have a solution, they just keep making problems. I’m talking about City Council, not the people. City Council doesn’t want to come up with a solution. Just, “Get them out of there. They’re going to move somewhere else. Get them out of there, and they’re going to move somewhere else.”

Harm Reduction:

**Harm Reduction**– any program, organization, or action which attempts to mitigate the negative side-effects of drug usage. This can include housing programs, safe injection sites, or diversion programs.

**Pre-Arrest Diversion**– refers to city programs where people can avoid getting convicted of drug-related crimes. This often involves demonstrating enrollment in rehabilitation programs.

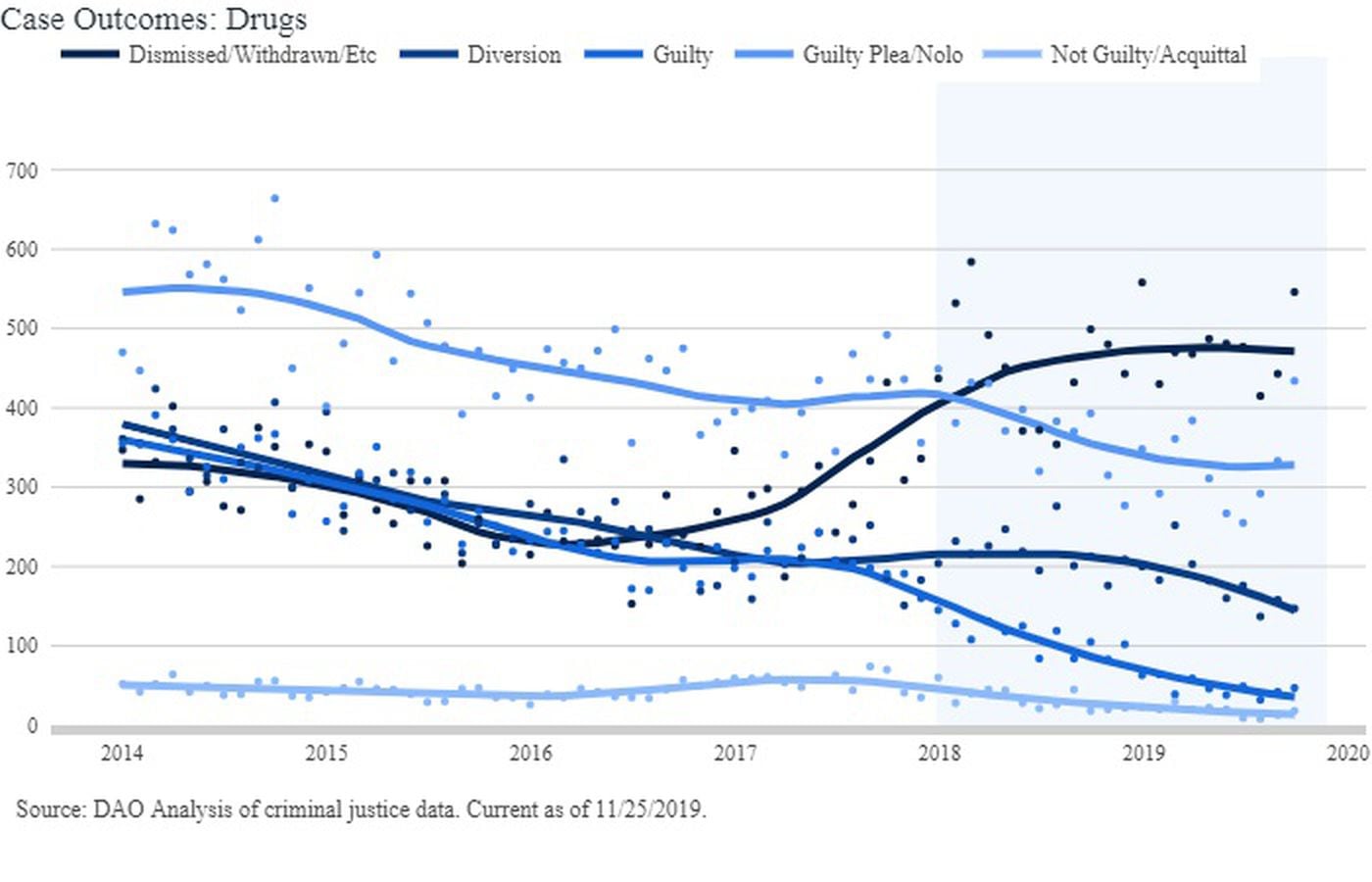

Image: Contains rates of conviction for drug-related cases in the city of Philadelphia. Recent years have seen an increase in the cases dismissed or withdrawn and a decrease in charges that ended with a guilty conviction (Melamed).

Paul : That’s a position that we face in terms of… … deprivation that exists in the schools and in the jobs and the opportunities, mass incarceration, and now they want to be, now they want a lighter approach to drug users and they want to do harm reduction, they want to open up an overdose prevention site. Which seems good, but it doesn’t get to the problem. What are your feelings, what are your specific feelings, and then the feelings of people in your world?

Moses: I’m for harm reduction, I’m completely for harm reduction. My family, immediate family and most of my family is for harm reduction. The ones that understand what harm reduction is, a lot of people have a misconception. They don’t understand harm reduction. People aren’t dumb… …but they’re not always highly educated. So when you talk to them with really big words and they don’t understand it, and the first thing they say is, “You just want to let them do drugs. That’s all you want to do.”

So to me, in order to break it down, you’ve got to just break it down to them in layman’s terms. I feel that harm reduction is necessary, because it’s going to save lives. It’s going to save families. It’s going to bring awareness. For people that don’t understand that and if you don’t expand from that, they’re going to think that it’s just about people shooting up, it’s just a place where people are going to shoot up and kids are going to see they’re shooting up, they’re going to think it’s okay. Not understanding that they have a disease, a disease of addiction, and it just so happens that they may shoot up heroin. That’s their addiction, so we need to help them not hurt themselves. Because it’s harm reduction, we’ve got to help them.

Paul: When we’re talking about tax dollars, people need to be educated. I can’t see it totally. What are your views of some of the hypocrisy of our state? How do you come to harm reduction, even though there are so many things?

Moses : The things that made me want to work with harm reduction and why I believe in harm reduction is because my family members. The ones that didn’t get the chance to have a place to go where they would have resources, like you can talk to a counselor or take a shower. At our house, they weren’t allowed to take a shower. I wish that there was something like this for my uncles, because two of them would be alive right now. I had a girlfriend a few years ago… …who died of an OD, she was addicted to prescription pills and she died. So that’s it. To me, it’s so close to me that I can’t see why I wouldn’t want to help people that were suffering.

This graph displays the role of Benzodiazepines (like Xanax) in overdose deaths, emphasizes Moses’ message that “pills” can be as deadly as opioids. Source: Whelan

When I got out, they had me on the same opioids, I didn’t even know I was addicted to Xanax, I was addicted to pills, had no clue until they took me off medication. When they took me off medication, I started having withdrawals and that’s when I knew I couldn’t take … Even to this day I don’t take, the most I take is Tylenol, because to me, I’m afraid that I’m going to get addicted again and given our family’s history, I don’t want to go to anything that’s strong to feel better.

How to Help

Moses: The people that are saying, “Why are we helping?” Again, it’s a lack of information or education on their part. Or a lack of a connection. Because if it was one of their people, the first thing they would say is, “Why don’t you help my son or my daughter? My daughter OD’d and nobody helped them.” Until it touches some people, they don’t care about it. That’s the reality. But everybody else, it’s just a lack of education pretty much.

Donate or Volunteer:

- Philadelphia Resilience Project:

- South Kensington Community Partners:

- Pathways to Housing:

- Creative Resilience Collective:

- Prevention Point:

- Safehouse Philly:

- Esperanza:

- Hace:

Everyday Suggestions for Combating Stigma and False Narratives:

This chart derived from the Office of National Drug Control Policy displays words that can be used to substitute stigmatizing language. Source: Elkins

- Be Informed

- “Stigmatizing attitudes against mental patients are more prevalent among less educated and more competitive groups.” (Davidson)

- Remember people are people, and that empathy for those who are suffering “should not be conditional” (Shihipar).

- Avoid Stigmatizing Language

- Have Conversations

- Listen to Lived Experiences

- Be aware that there’s always more to the story then what’s written on the page

Acknowledgements

Moses: For sharing his story and lived experiences.

Project Advisor Dr. Sebastiàn Ramírez: For working closely with us and advising us at every stage of our project

Professor João Biehl: For granting us the tools and theoretical frameworks to think critically about health from the perspective of the individual and the institution

Onur Gunay, Ipsita Dey, and Nikhil Pandhi – For your dedication to ensuring this course continued smoothly and for providing us with amazing feedback on our critical reflections throughout the semester and helping us to improve our interaction with scholarly sources in Anthropology

Service Focus Faculty Adviser Dr. Yi-Ching Ong: For guiding us through a year of reflection, mindfulness, and service.

Senior Educational Technologist Ben Johnston: For being a WordPress Wizard, helping us with the technical organization of the site, and allowing us to use his Annotation word press theme.

Dr. Jeff Himpele: For aiding with the visualization of this project and lending his photos.

Our Community Partner The Creative Resilience Collective: For giving us the opportunity to aid in their mission of combating stigma and working towards a more equitable future

Readers: Thank you for taking the time to read our webpage. We hope this has impressed upon you the importance of decriminalization as well as the potent impact the drug crisis has on many lives in North Philadelphia.