Who gets to define what’s ‘racist?’ (original) (raw)

One key insight of the “discursive turn” in social research is how concepts are defined, and by whom, reveals a lot about power relations within a society or culture. These definitions are not just reflections of social dynamics, but can have important socio-political consequences downstream: they can help legitimize or delegitimize individuals, groups and their actions; they can render some things more easily comprehensible and others less so; they can push certain things outside the realm of polite discussion, and introduce new elements into the language game.

The term “racist” is no exception.

In the past, racism primarily denoted overt discrimination, bigotry, or racial animus. Incidents of this nature are far less common and far less accepted than they were in previous decades. Indeed, in contemporary U.S. society, one of the very worst charges that can be leveled against someone – especially a white person – is to accuse them of being racist.

On balance, both of these developments are great.

However, as a function of the increased social capital at stake when accusations of racism are made, and the diminishing opportunities to leverage that capital by “calling out” obvious cases of racism – the sphere of what counts as “racist” has been ever-expanding – to the point where it is now possible to qualify as “racist” on the basis of things like microaggressions and implicit attitudes.

One particularly unfortunate aspect of this concept creep – justified under the auspices of empowering people of color – is that relatively well-off, highly-educated, liberal whites tend to be among the most zealous in identifying and prosecuting these new forms of “racism.”

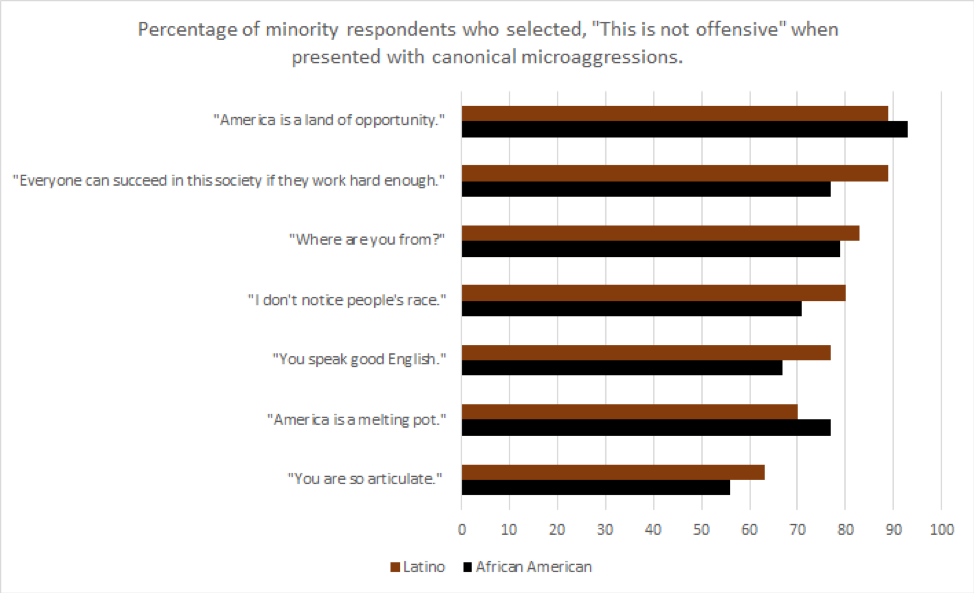

For instance, a recent Cato study presented Americans with a series of canonical microaggressions and asked whether or not they were offensive. Hispanic and black respondents overwhelmingly said they were not:

Yet, white college students and graduates were significantly more likely than the average black or Hispanic respondent to brand these statements as “offensive.” This effect was especially pronounced among white highly-educated respondents who identified with the left.

This pattern is hardly unique to the Cato study. For instance, a recent study by More in Common found that highly-educated, upper-SES white urbanites were far more supportive of “political correctness” and political revolution than minorities tend to be. Looking at GSS and ANES data, highly-educated whites tend to be more ‘woke’ on racial issuesthan the average black or Hispanic; they tend to perceive much more racism against minorities than most minorities, themselves, report experiencing; they express greater support for diversity than most blacks or Hispanics; they report more favorable attitudes towards people of racial/ ethnic ‘outgroups’ over their ‘ingroup’ – and are the only ethnic or racial group to exhibit such tendencies.

How can this phenomenon be explained?

One approach might be to argue that relatively well-off and highly-educated liberal whites — by virtue of their college education and higher rates of consumption of ‘woke’ content in the media, online, etc. — simply understand the reality and dynamics of racism better than the average black or Hispanic. I would strongly advise against anyone taking a stand on that hill.

What is more plausible is that many whites, in their eagerness to present themselves as advocates for people of color and the cause of antiracism, neglect to actually listen to ordinary black or brown folk about what they find offensive, or what their racial priorities are.

White elites —who play an outsized role in defining racism in academia, the media, and the broader culture — instead seem to define ‘racism’ in ways that are congenial to their own preferences and priorities. Rather than actually dismantling white supremacy or meaningfully empowering people of color, efforts often seem to be oriented towards consolidating social and cultural capital in the hands of the ‘good’ whites. Charges of “racism,” for instance, are primarily deployed against the political opponents of upwardly-mobile, highly-educated progressive white people. Even to the point of branding prominent black or brown dissenters as race-traitors (despite the reality that, on average, blacks and Hispanics tend to be significantly more socially conservative and religious than whites).

The politicized nature of these accusations is not lost on their intended targets. The blowback against a perceived overuse of “racism” charges seems to have significantly contributed to the rise of Donald Trump and other demagogic figures in the U.S. and Western Europe. It is primarily marginalized and vulnerable populations who tend to suffer when such figures come into power (upwardly mobile highly-educated whites, regardless of their political leanings, are still doing just fine). Indeed, evidence is growing that many fashionable formulations of “racism” (and antiracist activism) may be directly pernicious for people of color.

For instance, a recent metanalysis on microaggressions found little empirical substantiation for the harm claims advanced in the literature. Yet there is abundant research demonstrating harm caused by heightened perceptions of racism, discrimination, racialized violence, and racial inequality. There are very well-established and highly-adverse impacts on the psychological (and even physical) well-being of people of color when they perceive more racism, racial inequality, and discrimination. That is, we have not (yet) been able to empirically verify that microaggressions are typically harmful, nor have we been able to effectively measure the extent of that harm. (Again, the vast majority of blacks and Hispanics find even the paradigm cases to be inoffensive). However, we have ample reason to believe that sensitizing people to better perceive and to take greater offense at these “slights” actually would cause harm.

Similar problems emerge with respect to other popular approaches: training on ‘multiculturalism’ seems to reinforce race-essentialism among those who go through it; teaching whites about racial privilege seems to do little to change attitudes or behaviors towards African Americans — it merely increases resentment against lower-SES whites. Metanalysis after metanalysis fails to find strong empirical links between “implicitly racist” attitudes and actual racist behaviors “in the world.” It seems as though the primary effect of such training, among those who go through it, is higher levels of racial resentment. Yet entire industries have cropped up to help people understand and fight their implicit racial biases.

Why?

The short answer is that these approaches — despite being demonstrably ineffective (or even counter-productive) — are relatively easy to execute. They allow institutions, and social elites, to gesture that they are “on board” with antiracism and “doing something” about racialized inequality without actually making major changes to the way they do business. Yet, as Cyrus Mehri aptly put it, “When you keep choosing the options on the menu that don’t create change, you’re purposely not creating change. It’s part of the intentional discrimination.”

We must transform how antiracism work is carried out. An important first step is to actually listen to people of color about their priorities and concerns, rather than selectively elevating (often non-representative) spokespeople who say what educated white liberals want to hear. History the U.S. and abroad is replete with examples of grievous harm caused by well-intentioned technocrats and ideologues when they fail to sufficiently consult and collaborate with the populations whose interests they are ostensibly seeking to advance. Antiracist campaigns are no exception.

Musa al-Gharbi is a Sociologist at Columbia University.