The Girl and the Faun: Eden Phillpotts, His Crime Fiction and His Strange Relationship with His Daughter Adelaide (original) (raw)

“No biography or autobiography is true, because no one in his senses tells the truth about himself….Whoever wants to know me can find me in my work.”

Article continues after advertisement

–Eden Phillpotts (quoted in Reverie, 1981, by his daughter Adelaide Ross)

“Mr. Phillpotts has always avoided personal publicity like the plague.”

—Plymouth Western Morning News, 6 April 1921

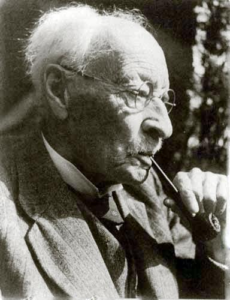

Novelist and playwright Henry Eden Phillpotts (1862-1960) once was famed, in both the United Kingdom and the United States, as the “Thomas Hardy of Dartmoor,” largely on the basis of his lengthy, critically-acclaimed “Dartmoor cycle” of novels like The Secret Woman (1905), The Thief of Virtue (1910), Widecombe Fair (1913) and Children of Men (1923). “If living characters, perfect plot construction, imaginative breadth of canvas and absolute truth to life are the primary qualities of great realistic fiction,” pronounced one dazzled American reviewer in 1910, “Mr. Phillpotts is one of the greatest novelists of our day.” Yet in our day Eden Phillpotts is by far best-known, among fans of vintage mystery, for having encouraged his young neighbor Agatha Miller, an aspiring author in the salubrious Devon seaside resort town of Torquay, to carry on with pursuing a writing career.

Article continues after advertisement

Upon reading the manuscript of Snow upon the Desert, her first novel (still unpublished), Eden Phillpotts sagely advised the nineteen-year-old Miss Miller, who had come to him at the urging of her mother: “You have a great feeling for dialogue. You should stick to gay, natural dialogue. Try and cut all moralizations out of your novels; you are much too fond of them, and nothing is more boring to read….leave your characters alone, so that they can speak for themselves.” Sending Miss Miller’s manuscript and letter on to his agent, Hughes Massie, Phillpotts delicately informed his supplicant: “He will criticize this for you and tell you what chances it has of being accepted. I am afraid it is not easy to get a first novel accepted, so you mustn’t be disappointed.”

Phillpotts also later perused “Being So Very Willful,” a short story (now lost) by Miss Miller. Of the story he commented most encouragingly, although he warned Miss Miller of the great dangers Life posed to Art, particularly for marriageable young women:

All is going exceedingly well with your work and should life so fall out for you that it has room for art and if you can face the uphill fight to take your place and win it, you have the gifts sufficient. I never prophesy; but I should judge that if you can write like this now you might go far. However life knocks the art out of a good many people and your environment in the time to come may substitute for the hard road of art a different one. The late Mrs. Cragie [Pearl Cragie, who wrote under the pen name John Oliver Hobbes] was about the only woman I know who stuck to hard work for love of it.

Years later, after she had become one of the world’s most successful fiction writers, Agatha Miller–now known to her vast reading public as Agatha Christie–retained great fondness for the elder author who had given her youthful writing promising words of praise. In 1932 Christie dedicated her widely admired Hercule Poirot detective novel Peril at End House, which is set at a fictionalized Torquay, to her onetime mentor, in gratitude “for his friendship and the encouragement he gave me many years ago.” When Eden Phillpotts died on December 29, 1960, at the venerable age of ninety-eight, Christie, then herself seventy years old, penned a short but affectionate newspaper tribute to him, singling out for praise his 1910 children’s novel The Flint Heart. (There is scarcely a fiction genre which Phillpotts left untouched during his eight decade writing career.) In her posthumously published Autobiography (1977), Christie again warmly praised Phillpotts, memorably recalling him as “an odd-looking man, with a face more like a faun’s than an ordinary human being’s.”

Certainly Eden Phillpotts was no ordinary human being. An extraordinarily prolific author (even more so than Agatha Christie), Phillpotts from his longtime fastness in Devon, where he relocated from London around 1890 (the year Agatha Christie was born), published, it is said, over 250 books, including almost 120 novels, about a third of which are works of crime, adventure and mystery fiction. Back in 1909 he had told Christie, concerning her novel Snow upon the Desert: “You have two plots here, rather than one, but that is a beginner’s fault; you soon won’t want to waste plots in such a spendfree way.”With ever so many books left to write, Phillpotts himself emphatically was not one to waste plots.

Eden Phillpotts’ last novel–entitled, appropriately enough, There Was an Old Man (it is not a mystery)–was published in 1959, just a year before the Old Man died. His final mystery novel, George and Georgina, appeared but seven years earlier in 1952, when the author had entered his ninetieth year. This was just over seven decades after the appearance of his first mystery adventure tale (and first published book of any sort), the Queen’s Quorum novella My Adventure in the Flying Scotsman, which Phillpotts published in 1888, when he was twenty-five years old. It appeared in book form the same year as did his contemporary Arthur Conan Doyle’s debut Sherlock Holmes adventure, A Study in Scarlet.

Article continues after advertisement

Phillpotts continued to publish occasional mystery-adventure novels over the next couple of decades, like his first published novel, The End of a Life (1891), along with A Tiger’s Cub (1895), The Golden Fetich (1903), The Sinews of War/Doubloons, (1906), The Statue, (1908), and The Three Knaves, (1912). (He co-authored Sinews and Statue with noted writer Arnold Bennett, doing the plotting himself while Bennet did the actual writing.) However, it was not until 1921, when he was nearly sixty years old, that Phillpotts published his first full dress detective novel, The Grey Room. This tale, which was much praised by critics, followed his former neighbor Agatha Christie’s epochal debut mystery, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, into print by less than six months, at the dawn of the Golden Age of detective fiction. Between The Grey Room and George and Georgina came nearly thirty additional crime and detective novels, including four published in the Twenties under an alliterative pseudonym, “Harrington Hext.”

During the 1920s Phillpotts, like his very slightly younger mainstream, mystery-dabbling novelist contemporary J. S. Fletcher, was deemed, particularly in the United States, one of the major English contributors to detective fiction, on the basis of the nine mystery novels and single book of crime and suspense stories which he produced during that decade. These were, under his own name, The Grey Room, The Red Redmaynes (1922), A Voice from the Dark (1925), Jig-Saw/The Marylebone Miser (1926), The Jury (1927) and his short story collection Peacock House (1926), along with the quartet of Harrington Hext crime novels: Number 87 (1922), The Thing at Their Heels (1923), Who Killed Cock Robin?/Who Killed Diana? (1924) and The Monster (1925).

Mystery writer S. S. Van Dine (pseudonym of hoity-toity critic and public intellectual Willard Huntington Wright), who as the creator of the painfully aesthetic sleuth Philo Vance was himself the bestselling and most highly praised author of crime fiction in the United States during the Twenties, numbered among the many admirers of Phillpotts’ crime writing in that decade (and of Hext’s, whom Van Dine correctly identified as Phillpotts). “Eden Phillpotts,” Van Dine emphatically declared, “has written some of the best detective stories in English.” Another extremely popular American Twenties mystery writer, Carolyn Wells, who was Phillpotts’ elder by a few months, pronounced: “Of all the detective stories I have ever read, I consider those by Eden Phillpotts the best and finest. His work seems to grow better with each book.” Author and New York Herald literary critic James Lauren Ford ranked Phillpotts as a detective novelist along with Arthur Conan Doyle, Wilkie Collins and the aforementioned J. S. Fletcher, the latter of whom, though like Phillpotts largely forgotten today, was the most popular “new” English mystery writer in the United States during the Jazz Age.

Among other things, Phillpotts contributed to the fabulist “room-that-kills” and “locked room” mystery subgenres with The Grey Room and Jig-Saw and the serial killer and jury deliberation subgenres with The Red Redmaynes and The Thing at their Heels and The Jury. Jig-Saw anticipates modern crime fiction in its startlingly amoral conclusion, while The Monster deals with child murder and psychopathy. Additionally Phillpotts contributed one of the finest twists of the period in Who Killed Cock Robin?, a book much lauded by critics of the day, who also praised Phillpotts’ ability, in this and other of his crime novels, to bolster the mystery structure with the values of the mainstream novel (credibility of characterization and intellectual/philosophical merit), while retaining the requisite formal puzzle elements. As one impressed reviewer put it at the time, Phillpotts’ crime fiction possessed, atypically for the genre, “qualities of psychological understanding, of interpretation of character and motive, together with an admirable force, fineness and spirit in the narrative style.”

Between 1928 and 1930, the years of his first wife’s death and his remarriage, Phillpotts produced no crime fiction, but after that he soon picked up the pace with a vengeance. In the 1980s academics and devout mystery fans Jacques Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor included Phillpotts’ 1931 detective novel Found Drowned in their 100 Classics of Crime Fiction series, while the author’s grimly realistic Book of Avis crime trilogy, consisting of Bred in the Bone (1932), Witch’s Cauldron (1933) and A Shadow Passes (1933), is, to my mind, his most important overall contribution to the mystery genre. The charming miniature Mr. Digweed and Mr. Lumb (1933), and the brooding Gothic mystery Lycanthrope: The Mystery of Sir William Wolf (1937), deserve mention as well, along with the dual 1935 crime novels The Wife of Elias and Physician, Heal Thyself/The Anniversary Murder. Yet on the whole it must be admitted that Phillpotts’ reputation as a crime writer, while still deemed quite high in many critical quarters, generally began receding in the Thirties, even as crime fiction began making up more and more of his output as a writer. (By my count, Phillpotts between 1931 and 1944 produced nineteen mystery novels, about half of the novels he published in this period.)

As newer, more modern talents triumphantly marched onto and occupied the field of fictional crime and detection during the Depression years (e.g., Christie herself, along with, for example, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh, John Dickson Carr, Nicholas Blake, Michael Innes, Ellery Queen, Mignon Eberhart and Dashiell Hammett) and other mystery modes developed (manners, hard-boiled, madcap, couples), Phillpotts’ stately prose more and more came to seem unpardonably old-fashioned and redolent of wordier narratives from the Victorian era: long-winded and digressive, ponderous and platitudinous. Too often he failed to heed the advice he gave Agatha Christie about not moralizing in writing. Representative of others of his/her type, one American reviewer tellingly complained of Phillpotts’ Lycanthrope that, while it had “found favor among English readers…it…will not stir up much enthusiasm on this side of the Atlantic, where Americans like their stories studded with more comedy.”

By the Forties influential New York Times crime fiction critic Anthony Boucher, himself an able mystery writer, apparently felt perfectly comfortable with openly deriding in print Phillpotts’ skills as a murder monger. In a review of the elder author’s very late effort They Were Seven (1944), published when he had reached the advanced age of eighty-two, Boucher bluntly asseverated of the Old Man of Mystery: “His characters are wooden, his dialogue unspeakable, his books are endless and actionless and his plots are stupidly unfair….the Emperor has no clothes on.” Of Phillpotts’ slightly earlier Flower of the Gods (1943), Boucher sarcastically warned: “A doctor’s prescription should be required for this powerful soporific.” In similar fashion a notice of the author’s mystery Ghostwater (1941) in the Lexington Herald was scathingly headlined “Eden Phillpotts Reaches New Heights in Plot Dullness.”

Another, anonymous American reviewer remarked more judiciously of Phillpotts’ Awake, Deborah! (1941) that the novel, “in contrast with the more generally popular murder mystery…is handled with a sort of detachment which is likely to prove annoying to customers who like to be drawn into the spirit of events. Because of the absence of animation, the book develops little tenseness….Notwithstanding, the plot is excellent.” Yet another anonymous American reviewer similarly chimed in bemusedly of Awake, Deborah!: “The real mystery in this Eden Phillpotts mystery story is how Eden Phillpotts, with his leisurely style and incredibly stilted language, yet manages to hold the reader’s attention to the end….It sounds impossible, but as a matter of fact it is enthralling.”

Even in the fast-moving Forties, Phillpotts’ mysteries continued to have unapologetic advocates, such as noted Midwestern author August Derleth, a man who like Phillpotts was a prolific dabbler in myriad literary genres, including horror and mystery. In his notice of Flower of the Gods in the Madison, Wisconsin Capital Times, Derleth dubbed Phillpotts “one of the most skilled stylists in the mystery field, as well as the author of some classic detective novels like The Red Redmaynes.” Derleth deemed Flower of the Gods “Class A mystery reading, a book no literate fan will want to miss,” adding enthusiastically of the author: “His mysteries are consistently good and well-written.”

Aforementioned Phillpotts fan Carolyn Wells began corresponding with the author a few years before her death in 1942 and was greatly delighted when he dedicated his detective novel Monkshood to her, complete with a poem paying tribute to her own skills as a mystery writer: “Madam, you’ve led us through some shady places/And sounded wickedness of high degree/Yet added your incomparable graces/To charm the heart of ever mystery.” Wells divulged to newspapers in 1939 that she “was so much excited” on receipt of [_Monkshood_] that she “sat up until 5 a.m. reading it.”

For his part hugely popular Westerns writer Louis L’Amour, no stranger to action in fiction, in his notice of Awake, Deborah! in his book review column in the Oklahoma City Daily Oklahoman avowed that for a quarter century “Eden Phillpotts…has been turning out lively stuff, and always with a difference. This novel is no exception.” In The Rotarian another prominent author (and mystery writer), Vincent Starrett, in his review of Flower observed: “One of the best of the old masters still living is Eden Phillpotts, an important novelist in several fields….His latest puzzle, Flower of the Gods, is told in the familiar Phillpotts manner, which is leisurely, informative, and almost excessively literate….This is a crowded, old-fashioned story and sometimes, it may be admitted, it is slow going, but as a change from, say, Queen and Hammett, it can be recommended to readers of an older school.”

Britons, of course, generally took less issue with “dullness” in their mysteries than sensation-addled Americans. (As Raymond Chandler famously backhandedly pointed out, the British made the best dull detective writers in the world.) A reviewer for the Torquay Herald Express went further than most with his/her unbounded praise for Phillpotts (perhaps unsurprisingly, given the author’s status as a local literary lion), avowing of Awake, Deborah!: “The story keeps the reader palpitating with excitement. Readers of Phillpotts’ books who may imagine that the author revels only in old-fashioned Devon stories are pleasantly disillusioned….It is an enthralling book.”

During the eighty years from that point up to the present day, however, it is fair to say that Phillpotts’ reputation, both as a “serious” mainstream writer and author of crime fiction, has drastically waned, particularly after his passing in 1960. Yet in my opinion as a longtime aficionado of vintage mystery, the time is overdue for at least a modest reassessment and revival of the author’s crime fiction.

*******

Surely a major obstacle to reviving Phillpotts’ writing, however, emanates from the faun-like man himself, to allude to Agatha Christie’s discerning description of him. This obstacle is centered, like the life of the mythical faun, upon the author’s physical expression of sexual lust. In 1892, when he was thirty years old, Phillpotts—a striking-looking man with rufous hair, cat’s eyes, a noble nose and a luxuriant mustache that Hercule Poirot might well have envied—wed the slightly younger Emily Topham, daughter of a prosperous Cheshire farmer. (The Topham family was historically connected with the famed Lancashire Tudor manor house Speke Hall.) Emily bore her husband two children: a son, Henry Eden (1895-1976), named for his father, and a daughter, Mary Adelaide Eden (1896-1993), named for her father and his mother.

The latter progeny—Adelaide as she was known—grew up to be an able fiction writer in her own right and lived nearly as long as her very long-lived father, passing away at the age of ninety-seven amid the era of Bill Clinton and John Major. During his life Eden Phillpotts additionally was rather prominent as a playwright and in the Twenties, at the height of his playwriting success, he urged his daughter to collaborate with him. His hit rustic comedy The Farmer’s Wife, drawn from his 1913 Dartmoor novel Widecombe Fair, enjoyed over 1300 performances on the London stage between1924 and 1928 (making it the most performed London play in the twentieth century until the advent of Agatha Christie’s The Mousetrap); earned more than 300,000 pounds (about eighteen million pounds/twenty-one million dollars today); helped give rise to the careers of actors Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson and Cedric Hardwicke; and was adapted as a film by Alfred Hitchcock in 1928. In addition to writing her own solo work, Adelaide eventually collaborated with her famous father on several plays, the best-known of which is the comedy Yellow Sands, Phillpotts’ second most successful stage work.

There were darker leaves in this seemingly sunny Phillpotts family album, however, for it appears that Eden Phillpotts, his writing genius notwithstanding, possessed many of the less attractive traits of the Victorian patriarch of iconoclastic fiction and film, being heartlessly domineering, piously puritanical and revoltingly hypocritical at the same time. By his daughter’s own later recollection, Phillpotts cruelly blighted much of her life in its most tender and susceptible bud.

In 1976, shortly after the death of her elder brother Henry, the late English professor James Dayananda (1936-2019) interviewed Adelaide for a book he was writing about her father, Eden Phillpotts: Selected Letters, later published by University Press of America in 1984. In the book Dayananda writes that Adelaide Phillpotts “remained unmarried until the age of 55….In 1951 she married Nicholas Ross, an American from Boston settled in Britain, much against the wish of her father. Eden Phillpotts cut her off, and never met her again after her marriage, despite several attempts of Adelaide at reconciliation….The letters…throw some light on the ups and downs of the relationship between Eden and Adelaide Phillpotts.”

In her 1976 interview with Professor Dayananda, Adelaide Phillpotts shockingly declared that her father had sexually abused her as a child (as far back as when she was six or seven) and that until 1929 he kept up with her, off and on, an intimate relationship, elaborated by her, as quoted by Dayananda, as “fondling, kissing, intercourse (not penetration).” (What we would call outercourse today.) Perhaps not coincidentally, the year 1929 was a year after the death of Phillpotts’ first wife Emily from cancer and when Phillpotts, approaching seventy years of age, wed his second wife, a thirty-nine year old cousin named Lucy Robina Joyce Webb, daughter of an Exeter surgeon who resided at the city’s now-famed Tudor House. Robina Webb Phillpotts was merely six years older than her stepdaughter. Adelaide also claims that throughout his life her father was obsessively jealous of her relationships with other men and that he never spoke to her again when in 1951 she finally did marry, in defiance of his vehemently expressed will.

This is, of course, a disturbing bunch of revelations, to say the least, like something out of the darkest pages of a modern crime novel, perhaps one by Julian Symons, whose 1978 mystery The Blackheath Poisonings is as scabrous a portrayal of hypocritical Victorian sexual misdeeds as one could get. (Fittingly, Symons in his idiosyncratic history of crime writing, Bloody Murder, brutally dismisses Phillpotts as the author of “among the most ridiculous [mysteries] of the time.”) But how persuasive are Adelaide’s allegations?

Certainly some of the letters from Eden Phillpotts to Adelaide that are included in Professor Dayananda’s collection, in which he invariably addresses her by such endearments as “My precious love,” “My dearest love,” “My sweet love,” etc., are suggestive (even if there is no “smoking gun,” so to speak):

“Today I had hoped to welcome my precious girl and have my arms around her again.” (1914, when Adelaide was eighteen)

“But I am exceedingly thankful you did what you have done [breaking off an understanding with a man; see below] for it would be destructive to your art to tangle yourself in an engagement to be married at present and I should deplore it exceedingly. Plenty of time for that.” (1917, when Adelaide was twenty-one)

“I was not surprised after your first mention of that Jew and his politeness to hear he wanted you. The damned swine saw you were alone. You must not go to a hotel in future where that sort of vermin harbours for he might have been wickeder than he was and have planned to compromise you in some way.” (1929, when Adelaide was thirty-two)

In these letters Phillpotts sounds alternatively cloying, possessive and controlling. In the last of them, composed as the din from the Twenties still roared, the author arguably sounds more like a jealous lover than a sternly loving Victorian papa, especially when one considers that his daughter had long ago entered the marriageable age. However, we have more than the words of Professor Dayananda and Eden Phillpotts to turn to in this matter: there are those of the putative victim herself, Adelaide, as set down in her 1981 memoir, Reverie, published when Adelaide was eighty-five years old.

*******

In Reverie Adelaide Ross, as she was then known, paints a poignant portrait of a woman whose life was, to a great extent, controlled and cruelly circumscribed by a tyrannical, egoistical parent who seemingly expected all others within his household (but particularly her) meekly to submit to his will as a self-professed Great Man of Letters, whose own needs and desires must necessarily come first. (In the Census of 1911 Phillpotts grandly designated his profession as just this: man of letters.) Yet at the same time, indicative of the complexity of human nature, Adelaide is greatly admiring of her parent and sadly regretful of the fact that he ended all contact with her when, well into her middle age, she made a marriage of which he disapproved.

In Reverie Adelaide Ross, as she was then known, paints a poignant portrait of a woman whose life was, to a great extent, controlled and cruelly circumscribed by a tyrannical, egoistical parent…

Eden Phillpotts, having been one of three boys born in India into a family of clerics and colonial civil servants (he was a great nephew of the long-serving and famously tendentious Henry Phillpotts, Bishop of Exeter and nephew of William Phillpotts, Archdeacon of Cornwall), was originally intended for the Church himself. However, at the age of thirteen Phillpotts, enrolled in school in Plymouth, Devon and already a determined agnostic and rationalist who bridled at attending “services three times every Sunday,” balked at the righteous expectations of his elders. As Adelaide enviously put it in Reverie: “My father, even as a child, flashed into their midst like a changeling….To have defied even his pathetic [widowed] mother whom he much loved, my father must have possessed a good deal of moral courage and strength of character, and perhaps the dawning consciousness of his genius, for in those days few children were free to express their wishes.” Years later Phillpotts defied the Lord Chamberlain when in 1912, on the recommendation of the Examiner of Plays, he decreed that the writer must delete and alter from his stage adaptation of his novel The Secret Woman several offending lines (such as “I saw the two of them thicken into one”), even though this defiance meant that the play could not be commercially performed in the country. Among those signing a petition in support of Phillpotts’ stance was Arthur Conan Doyle. Would that Phillpotts, recalling his own experiences, have allowed his daughter such freedom of expression within his own domain.

In the 1890s Phillpotts, after having spent much of the 1880s clerking with an insurance firm in London and fruitlessly dreaming of an actor’s life on the stage, established an independent life for himself as a creative writer at his home Eltham in Torquay. The author had fallen in love with Devon as a schoolboy and determined one day to return there; it is said that he never visited London again after 1910, despite the fact that he had a series of hit plays performed there. At Eltham House Phillpotts’ household consisted of himself, his wife and his son and daughter, along with the children’s devoted nanny, Lilla Hilliard Brewitt, nicknamed “Nan,” and a quartet of domestics composed of a cook, parlourmaid, housemaid and tweeny. Of Nan, Adelaide recalls fondly in Reverie that “her assets” were “infinite good nature, strong sense of the amusing and the ridiculous, ready laughter and inexhaustible patience, besides willingness uncomplainingly to put up with a dwarf salary. She was much closer to us than our parents, whom we saw only intermittently.”

“The Torquay of Agatha’s youth,” writes Agatha Christie biographer Laura Thompson, “was configurative, complete; an elegant land of its own with its crescents and terraces, its huge pale villas shrouded amid trees and hills, its rituals and structures and distant wildness. It was a watering place, gently restorative, the kind of town at which people arrived carrying letters of introduction….The resident families were of Agatha’s own class: middle, tending towards upper. The homogeneity was precious. Around her, all was protection and stasis.”

So, seemingly, it was with Adelaide Phillpotts. Despite her father’s freethinking on matters of religion and renown as the chronicler of the common folk of Dartmoor, Adelaide’s upbringing, like Agatha’s, was strictly bound by class considerations. “Nan was evidently not considered good enough to eat with the family but too good to eat with the maids,” Adelaide sardonically observed, “and had to eat her meals alone in a small room between the fore and aft quarters of the house, where she typed, made and mended clothes, and, if she had a moment to spare, practiced her wood-carving. In all the years she lived with us she never had one meal with the family; and Mother never called her by her Christian name.” When she went to church with her mother (Father did not attend services) and two little girls smiled upon her, Adelaide asked Emily whether she could be friends with them and was told freezingly: “Their parents keep a shop in town.” The two families’ respective wives and mothers did not call upon each other and leave cards, Nan later had to explain to a perplexed Adelaide.

Immediate neighbors of the Phillpotts household—ladies who did call and leave cards—when Adelaide was in her adolescence, were the spinster Ormerod sisters, Helen Jane and Gertrude Edith, who resided at St. Mary’s with a cook and housemaid, and the widowed Clarissa Miller, living on private means, and her daughter Agatha, who resided at Ashfield with a cook and parlourmaid. The Misses Omerod hailed originally from Elm Royd, a grey Georgian house in the town of Brighouse, Yorkshire.They had moved south to Devon after the death in 1879 of their father, Thomas Theodore Ormerod, a big wheel in Brighouse as a cotton and silk mill owner, wine and spirits merchant, and Superintendent of the Bridge End Congregational Church.(Apparently the congregants did not object to the wine and spirits.) Adelaide recalled the Ormerods as “little old sisters, devoted to children, served by two still older retainers who wore long back dresses and white aprons.[In fact they were not a great deal older than Adelaide’s father.]I was taken there to tea….[After the Great War they kept] a fox terrier, turned vegetarian and half-starved themselves.They story went that on her deathbed Miss Helen murmured over and over again ‘Roast beef and Yorkshire pudding!Roast beef and Yorkshire pudding!’Miss Gertrude died soon afterwards….”(Indeed, they passed away, respectively, in 1926 and 1928.)

As for the Millers, in the early years of the twentieth century Adelaide accompanied by Nan attended a local dancing class (her shy, diffident brother Henry refused to go with them), where the shining star in attendance was this dazzling young neighbor:

[She was] a flaxen-haired beauty of twelve called Agatha….wearing a blue silk accordion-pleated dress, who danced better than anyone else and was prettier. She lived near us but we did not see much of her until she grew up. One side of the saloon held a large mirror and on my sixth birthday I recollect standing in front of it and noticing my face for the first time. Then I caught sight of Agatha’s reflection: she was a thousand times nicer and cleverer than me.

Adelaide may have held herself in little esteem, especially in comparison with pretty and outgoing Agatha Miller, but there was someone who at this same time came to admire her intensely, with the adoration of a lover: her own father. In the early pages of Reverie Adalaide dutifully recalls her father’s innocent doings—“Father published two or three books every year…as the family prospered my parents spent longer abroad in France and Italy….Father’s avocation was gardening….People from all over the world came to see Father’s garden….”—before calmly dropping this bombshell into her narrative:

I had a mania for caterpillars, moths and butterflies and began to scribble rhymes about them, which Nan made me copy out and give to father for his forty-first birthday. His delight was astonishing. He went through each line and amended it. From that moment he encouraged me to write.

He had begun deeply to love me. I think he looked on me as an extension of himself, for he would take me into his bed and fondle me, compare my limbs with his and say ‘Look! Your hands and feet are just like small editions of me. You’re so like me. And you’re going to be a writer too.’ He kissed me all over and said: ‘You must never marry.” At six or seven that meant nothing to me, yet I did not forget those words, which all though my youth and afterwards were repeated. I loved him too, but only as a father, and for fear of hurting him I let him do whatever he liked.

Adelaide used to find relief from her father’s hard-pressed endearments and his quarrels with her mother by wandering about in her father’s famed Devon garden: “For me it was heaven itself. From adult conflicts in the house, when voices were raised in anger and jarring words broke forth, Henry escaped to the Tower Room to paint, I to the garden to play with my invisible ‘family’ who never quarreled, to that Arcadia of colours, forms, fragrance and wild creatures….”

In 1902 Adelaide and her brother Henry were first sent to school by their parents. Henry, observes Adelaide, “withdrawn and sensitive, whose world revolved around his painting, was a ready victim for bullying. But our parents, who had found him stubborn and difficult, were determined that he should be disciplined and brought up like other boys until he fitted in the conventional mold.” For the rest of his days (he died in his eighty-first year), Henry, who physically resembled his father but seemed utterly, though not without talent, to lack his father’s will and spirit, appears to have led a sad, lonely life, dabbling at his daubs but unable to discipline himself and deeming his life a worthless failure. Beginning at the turn of the century, Phillpotts famously published a charming series of “Human Boy” short stories about public schoolboys, collected in five volumes and The Complete Human Boy omnibus (1930), but the author evidently never could comprehend how to manage his own son. At school Adelaide, on the other hand, prospered and promptly fell deliriously “in love” with another girl named Nelly, “my first experience of that troubling state, at seven as delicious as at seventy-seven.”

Although she was periodically subjected to her father’s unwanted caresses, Adelaide was kept ignorant of the subject of sex itself and only learned of its many strange and sometimes wonderful manifestations in her early twenties by stealthily consulting books in her absent brother Henry’s tower room, which in his absence she used as a study: “[L]ooking through his bookcase, concealed at the back, I found some French paperbacks he must have bought in Paris, and Kraft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis, which he probably purloined from Uncle Mac’s [Herbert Macdonald Phillpotts] medical books. What a remarkable world was revealed!…I had no idea how varied sex could be….”

Adelaide hoped one day herself to enjoy a meaningful procreative sexual married life with a man. She recalled that when, having wed a certain handsome “Colonel Christie of the air force,” her pretty neighbor Agatha Miller returned home to her mother’s house Ashfield “to have her baby…two days after the birth [on August 5, 1919] I called to see her and hold little Rosalind. The infant’s body gave mine such an indescribable thrill that I told myself: ‘You must have as many of these as possible.’” Despite this desire, wistfully reiterated throughout Reverie, Adelaide did not marry until she was well into middle age and never would she bear any babies.

Adelaide had good reason to refrain from speaking of these things to her parents, staying on the sly, for throughout her teens and into her adulthood Eden and Emily attempted to keep her swaddled in cotton wool, as it were, where sexual matters were concerned (at least with other men besides her father). When in 1912, while she, a young lady of sixteen, was “strolling up and down Oakhill Road, reading Shelley, my supreme Comforter,” she recalled:

An old man came along, smiled and said ‘May I kiss you, my dear?’ I disliked kissing, except in daydreams, but the aged fellow seemed so pathetic that I offered my cheek and hastily withdrew, hoping he would not follow. So little did this unimportant meeting signify that I jokingly mentioned it at the luncheon table, while the maids handed round potatoes and greens. (Father ate cabbage twice every day.) An uneasy silence fell until they had left the room. Then father burst out: “How could you let that old lecher touch you? Have you not been told over and over again never to speak to strangers?” and unable to contain himself he stormed out of the room. (Lecher—a new word. I must look it up.) “But he was only a doddery old man,” I said to mother, and she replied: “They’re the worst! Didn’t you realize he was mentally undressing you?” That did jolt me. Whatever did she mean? She explained and added: “You might have caught syphilis.” (Another new word!) “What’s that?” I asked. She told me. I was aghast and enquired how long it would be before I caught it. “In about six weeks,” she said….So I was left with…the torture of waiting six weeks to find out whether I had contracted that shameful, horrible, disfiguring and perhaps fatal disease, which could make me mad. I fled to Nan. “Nonsense!” she tried to reassure me. “They’re frightening you—for your own good.”

Seventeen years later, it will be remembered, Phillpotts would fly into another apoplectic fury at the mere mention of a man (“_that Jew…damned swine…vermin_”) having gotten too close to his precious possession, his only daughter.

Phillpotts’ own interest in his female offspring had not receded with time, as recounted by Adelaide. To the contrary, “my father had grown more and more affectionate and continued to draw me ever closer to himself. But love him as I did, deeply, I remained secretly averse from physical contact, though not for the world would I resist him.” “You must never marry,” he would tell her over and over. “You must give yourself to art.” Had Phillpotts not intimated a few years earlier to that young, aspiring writer, nineteen year old Agatha Miller, that there were but few women who could balance matrimony and Art?

With the coming of the Great War, Adelaide made a tentative bid for freedom from her Father, if not Art. In 1916, when she was twenty years old, she won grudging approval from her elders to obtain employment with a “non-militant suffragette journal called the _Common Cause_….” (Phillpotts at the time was a Liberal who supported the women’s suffrage movement and other advanced notions, though after the war he became a Conservative who flirted with Fascism, while his daughter turned to Socialism.) Adelaide found herself called roundly home, however, after she fatally established a friendship with a young book publisher named Cecil, who imprudently asked her to marry him. The response back at Eltham was frenzied and most unfavorable:

….on a weekend visit to Aunt Frances I had mentioned our friendship and how we walked in green places by starlight. What a trusting fool I still was. She immediately wrote to my mother to warn her. Mother told Father and he was furious, though this was before the proposal, which I did not mention to anyone. The upshot was I was summoned home and told to wind up my work….

Father sternly rebuked me—in a letter, when I got home….he would not meet me face to face and left me the letter to find. He guessed that Cecil had offered me marriage and set forth all the disadvantages of any marital alliance: I must devote my life when the war ended to my art. I was hurt and mystified that he chose to write instead of talking. And I told him again and again that I had no intention of marrying anybody, though I knew my mediocre gift of art was not worth sacrificing children for; I wanted to have them. I was under no illusions about my work’s insignificance. Poor Father—he seemed so pathetic and unreasonable—he, the apostle of reason. Yet even then I doubted whether my work was the sole reason for his attitude.

Once he had his way yet again, with his daughter once more giving way to his whims, Phillpotts wrote pacifically to Adelaide, as quoted in the letter farther above, assuring her that all had worked out best for her Art.

With the end of the war Adelaide began successfully placing her writing with publishers, beginning with Arachne, a verse-play published in 1920 and continuing with Man: A Fable and a first novel, The Friend, which appeared in 1922 and 1923, respectively. She recalled during this time spending five weeks with her father sojourning at Princetown in Dartmoor, where

in the hot sunshine Father would stretch out amidst the bracken and cuddle me. I can see him now, his crooked nose, broken at school and not set, scarlet with sunburn, his light blue eyes reflecting the scenes to him so dear. I can hear the spurt of matches as he lit and relit his pipe, reclining in perfect contentment. But I felt as restless as the bounding bubbles on the river….Yet I could not spoil my father’s joy. These untranquil moods when my parent was tranquil made me feel guilty, not for desiring solitude but for not responding to his heart’s desire, though he thought I did. I loved him with my heart and soul, but not in any other way, and I used to wonder: “Did he ever think ‘I can’t keep her forever’”—I do not think so. (Long afterwards Nan told me that when I was a schoolgirl he had told her: “If Adelaide ever loves anyone more than me there will be trouble.”)

Adelaide continued to write and publish throughout the 1920s, dividing her time between Eltham and London, where she shared a flat with Gertrude “Jan” Stewart, a “[s]mall and plump” woman “with wide-apart blue eyes, long hair coiled in thick braids over her ears, and clear pink cheeks,” with a personality (“gentle and firm, humorous and tender, kind yet determined”) that much appealed to her. Gertrude herself was in an unsatisfactory relationship with a man married to an invalid wife. “I thought, my father need not dread a marriage,” Adelaide observed sardonically of her same-sex cohabitation with Jan.

Devoting herself to her Art, as Phillpotts demanded of her, in 1926 Adelaide published, in both the United Kingdom and the United States, Lodgers in London, a charming, well-reviewed light novel drawing on her own experiences in the City, and Ahknaton, a serious play about the idiosyncratic ancient Egyptian pharaoh who attempted to convert Egypt to monotheism. The latter work oddly presaged Agatha Christie’s own play of the same title and subject, written eleven years later. According to J. C. Bernthal’s Agatha Christie: A Companion to the Mystery Fiction: “Both Ahknatons share remarkable similarities, including some almost identical dialogue….” With her father that same year Adelaide additionally published Yellow Sands, another rustic comedy like The Farmer’s Wife that made a hit, albeit a smaller-sized one, on the London stage. Of this father-daughter collaboration Adelaide wrote, with typical self-effacement where her own work was concerned:

Now father suggested I should collaborate with him, in another country comedy, whose plot he had invented, and though I felt incompetent, I agreed to try. Writing to and fro, Father did all the vital work while I contributed two characters, some construction, action and dialogue. I would write a scene or two and send it to him, and he would greatly improve it and send it back for revision; but my father’s work needed no revision.

In 1927 Adelaide published Tomek the Sculptor, which in Reverie she called “my best work, most deeply felt.” A bemused American reviewer of the novel observed in her notice in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (headlined “Genius Has His Way with the Ladies”) that Tomek, a great artist, “is selfish though the whole book—to his mother, to his friends, to his mistress and to his wife—and they all love him desperately despite his selfishness.” One can draw one’s own parallels to Adelaide’s famous father.

At this same time Emily Phillpotts fell critically ill with cancer and during her decline Eden, who had been unfaithful to Emily with a succession of other women throughout their marriage, fell “passionately in love” with Robina Webb, a pretty cousin about three decades younger than he who was much around Eltham at the time, “helping out.” Nan, Phillpotts’ personal secretary since the children had gone to school, was grievously crestfallen at this turn of events, for, she sadly informed Adelaide, the author “had promised that should he ever be left a widower he would marry her.” Observed Adelaide: “This revelation quite amazed me.”

Adelaide’s amazement notwithstanding, she should have been as aware as anyone that Phillpotts put his sexual needs first and expected the women around him to fall compliantly in line with his masculine will. And largely they did. When she attained adulthood, Adelaide recalled, “Mother explained to me that [Father] had always needed other women in his life—he was very attractive to women—and he himself told me that all artists, especially writers of fiction and drama, must gather as much knowledge as possible about the other sex.” Presumably this precept was not meant to apply to Adelaide.

*******

As he neared his seventies Eden Phillpotts continued imperiously to exercise absolute dominion over those around him. After Emily finally expired in 1928, Adelaide recalls:

Father decreed that I should return to London, Nan should stop in the boarding-house, and Robina…should come to live with him until, in a year’s time, he married her….Henry would have a room in the boarding-house where Nan lodged [both of them were still residing there, singly, in 1939]. Jan and I were to find a site near London on which to build a cottage, for which [Father] gave us a thousand pounds.

Like the grand Victorian papa of fiction (though it was past midnight of the Jazz Age), Phillpotts had arranged everything to his and his young second wife’s satisfaction, if not that of his offspring and secretary. Adelaide settled with Jan into a solitary Surrey cottage overlooking the North Downs that they named Little Silver, after a village in her father’s Dartmoor chronicles. They remained at Little Silver until 1938, when they removed to the cottage Fernhill in the picturesque Dartmoor hamlet of Ponsworthy. “With two little bedrooms, kitchen/dining-room, and small living-room built on at right angles, it was all we needed,” recalled Adelaide. “Oil was used for lighting and cooking, and for water a spring bubbled out of a bank a few yards down the hill. After Little Silver nothing could be simpler.” Until the advent of the war, her father subsidized trips to Italy for the two women, who sometimes were accompanied by Henry.

Adelaide still yearned for marriage and children, relating how on one occasion at a public function in the late Thirties she met a “bonny young woman” named Stella Gibbons, author of the acclaimed comic rural novel Cold Comfort Farm, and was asked by Gibbons, “What is your greatest treasure?” “I could not think,” recalled Adelaide, and Gibbons continued triumphantly: “‘Mine is my baby daughter!’” To this Adelaide recalled sadly: “I wished that I, too, had a daughter to be my greatest treasure, and pictured myself making and ironing her dress for her first ball.”

Instead, Adelaide kept writing. Intriguingly, she recalls that around 1935 she and Jan wrote a “thriller called The Wasps’ Nest,” which was produced at the Nottingham Playhouse, “but I remember nothing about it.” This is very odd, as Agatha Christie published an Hercule Poirot short story, “Wasps’ Nest,” in 1928, which Christie adapted as a television play for the BBC in London in 1937, under the title “The Wasps’ Nest.” Were the two writers again in odd synchronicity with each other, as they were with Ahknaton?

In Reverie Adelaide rushes through the 1940s (both the years of war and peace), on her way to the epochal event of her later years: her marriage in 1951 to an American named Nicholas Ross. During this time she regularly visited her father at Kerswell, the tree-shrouded, gas lit Victorian Gothic mansion on the outskirts of the village of Broadclyst near Exeter where he and Robina had moved in 1929. The imposing edifice rather resembles the depiction of the titular End House on a Seventies Pocket paperback edition of Agatha Christie’s Peril at End House.

In 1944 Eden and Robina patriotically opened the grounds of Kerswell to the public to raise money for the Red Cross, an exceptional event in the lives of the attention-averse couple, who fifteen years earlier had kept their own marriage a secret from the press. Sounding rather like the fete in Agatha Christie’s 1956 Hercule Poirot detective novel Dead Man’s Folly, the event boasted “numerous stalls, sideshows and competitions, other attractions being the auction, a fancy dress and decorated vehicle parade for children and a display of physical training by the Broadclyst Flight of 1169 (Exeter) Squadron, ATC.” Over L250 pounds were raised (about 12,000 pounds/15,000 dollars today).

During 1950 Adelaide worked on a rural Cornish novel, Stubborn Earth (1951), a book which prompted one smitten Canadian reviewer in 1952 to proclaim: “While still with us, [Eden Phillpotts] has handed on his mantle to his daughter…she is able to wear it worthily.” Adelaide spent what would be her last Christmas with her eighty-eight year old father, who “continued to summon me to Kerswell and I always went.” There she assisted him with his gardening, where his hobby was now, Nero Wolfe like, raising gladiolas. “[M]y filiation with my father was nearly as close as before,” she confided. “He called one [of his gladiolas] after me.” Yet for the first time in her life, she admitted, “I saw only blankness ahead—vacancy, emptiness. I tried to break through, back into the mainstream of life, if only to anticipate a serene old age with Jan and Henry, when something extraordinary happened to turn our small world upside down….”

As happy as it made Adelaide, the advent of her unexpected late-in-life marriage forever sundered her relationship with her father, who, though he would live for another decade, would never speak to his daughter again, in a final petulant flourish of overweening dominion. The Old Man of Letters had decreed that his girl was never to marry and it soon became clear that he had manifestly meant what he said. It seems that Phillpotts would rather have had his offspring “die on the vine,” still faithful alone to her Art (and to Him), than to know any moments of real romantic and sexual bliss with a male rival.

In February 1951 Adelaide met James Richard Nicholas Ross, a “tall, dark, middle-aged” artist, writer and bibliophile a decade younger than she, and less than four months later she accepted his proposal of marriage. (Again recalling Agatha Christie, who would say the same of her father, she admiringly told Nicolas, who had told her that he had read and admired her father’s mythological novel The Girl and The Faun, that he resembled a faun.) With trepidation Adelaide wrote the Old Man informing him of her dramatic news and was curtly told in reply that she would be wise to get any “daft notion” of marriage out of her head. To a letter from Nicholas, Phillpotts did not deign to respond directly at all, rather sending a stern missive to Nicholas’ father in Massachusetts informing the man cuttingly that neither he nor Adelaide was in a position to “keep” his feckless and presumably fortune hunting artistic son. Thenceforward Phillpotts refused ever to see Nicholas, while both Jan, bitterly jealous of her displacement in Adelaide’s affections, and Robina, for reasons best known to herself, vociferously opposed the union. (“She did everything to turn him against us,” claims Adelaide of Robina.)

For her part, generous and loving Nan, now eighty and residing in cheaper rooms in another boarding house with Adelaide’s unhappy wayward brother Henry (who lived on a small annuity from his father), pled Adelaide’s case to Eden and Robina, sadly to no avail. Adelaide would never see her father again, though he lived throughout the rest of the decade. When on the occasion of his eighty-ninth birthday she wrote him a “loving letter to tell him I was coming,” Phillpotts responded with a telegram tersely commanding her “Do not come. E. P.” It was the last parental injunction she was ever to receive: she would not hear from him again, at least on this side of the grave.

Adelaide and Nicholas moved into a house in Kilkhampton, a coastal village located six miles north of the town of Bude in Cornwall. It was sixty miles due west of Kerswell House in Broadclyst, but it might as well have been half a world away. Named Cobblestones, the modest little structure was comprised of a living-room, a kitchen converted from a wash-house, a bedroom partitioned into two, reached by a narrow steep stair, and, over the kitchen, a bathroom with hand-pumped water from a well. Here Adelaide in her fifties truly learned the meaning of the phrase “love in a cottage.” She had found a handsome, intelligent, charming man whom she could love in a natural way, though tragically she now was well past child-bearing years–or at least healthy children, as she wistfully put it. Love had come too late in her life for that.

*******

During the Fifties and Sixties, the relics of Adelaide’s past peeled away from her, like rind from a shriveled fruit. In 1964 Eltham House was “pulled down and the garden swept away to make room for [an extension of South Devon Technical College].” Two years earlier, Agatha Christie’s beloved childhood home, Ashfield, had likewise been demolished, in order to make room for a housing estate.) Nine days after Christmas, in January 1966, Adelaide, approaching seventy, wrote Agatha Christie, now seventy-five, telling her old childhood acquaintance: “I remember you very well, and your dear mother. I remember quaint candlelit tea parties with the Misses Omerod….Torquay is much changed.”

The day after Christmas 1952, Nan, elderly and quite deaf, passed away, most symbolically, after having been knocked over in a rush at Paddington Station in London by an impatient young mother pushing a broad perambulator and hitting her head on a curb. “[T]hough hers was an obscure, unknown life,” observed Adelaide gratefully of Nan, “like countless others it was worth a thousand times more than the lives of many who are seldom out of the news and are perpetuated in history.” Nan, who had accumulated a hard-earned estate of 13, 544 pounds (about 400,000 pounds, or over 500,000 dollars today) left legacies to both her former charges at Kerswell. Adelaide and Nicholas whimsically spent hers “on a gypsy wagon, or varda, to stand in a corner overlooking the sea and sunset [at Cobblestones].”

Adelaide’s father may have written off his daughter for good and all, but he like his daughter admiringly corresponded with Agatha Christie. Of her “splendid work,” Phillpotts avowed to the Queen of Crime in 1955 (when he had entered his ninety-third year): “I watch with admiration how you retain your great gifts of invention, of character creation, for your people are as full of life as they have always been. That is a rare gift for a novelist….” Phillpotts singled out for praise Christie’s series sleuth Hercule Poirot (of whom the Queen of Crime was becoming royally tired), declaring: “[I] always set Poirot above Sherlock Holmes for the reason that he is a living man, as interesting in himself as his adventures. One develops a personal regard—almost an affection—for him….”

Newspapers dutifully noted Eden Phillpotts’ birthdays every passing year, and he continued to publish additional novels up through 1959. That year saw him having cataract surgery at the age of ninety-seven and the next year he caught a bad cold from which he only gradually recovered. On the occasion of his nighty-eighth birthday on November 4, 1960, however, Robina told the Exeter Express and Echo that her husband’s “health is good. He still gets up at 7.30 each morning but he goes to bed a little earlier in recent years—it’s generally ten o’clock now, not eleven….Another difference is that he no longer does any gardening. Apart from that, he is quite well, on the whole.” He had not been engaged in writing another novel since There Was an Old Man, but he was planning “to start writing some reminiscences.”

Less than two months later, however, on December 29, 1960, Adelaide and Nicholas were startled to hear her father’s death announced on the television news. Adelaide generously reflected: “I felt grieved for Henry’s sake, grieved that Father had never met Nicholas, grieved that every effort to secure a meeting had failed, and that I had lost ten years of his companionship. I remembered how we once we had loved each other….” Robina decreed that Eden’s ashes were not to be scattered, as he had wanted, on Pew Tor, where Emily’s had been placed (she and Eden had courted there), but rather “several miles away near Crockern Tor, where he had courted [Robina].” In the event heavy snowfall prevented Robina and Henry–Adelaide had not been invited to participate in the ceremony–from reaching that newly-designated destination, and Henry perforce had hastily to lay Eden’s ashes on the heath a few yards from the car and beat a prudent retreat before the vehicle became entrapped in the snow. This irony her father might have appreciated, Adelaide speculated, for arguably “his true spouse, his everlasting beloved, was Dartmoor itself, to whom he had always been faithful.”

[O]ne of the most versatile and voluminous of writers,” admiringly pronounced the Exeter Express and Echo at Phillpotts’ death. “[A] true Devonian if ever there was one; and posterity will remember him as one of the outstanding men whose names garland the story of this country.” Adelaide’s final verdict on her father, characteristically kindhearted where he was concerned, was that “he should be judged, as he wished, and it must be favorably, by his works….I like to remember the young father who told me stories about the Zagabog [a character in _The Flint Heart_], at seven encouraged me to write, and on the pianola played the music he knew I loved; the father who enjoyed picnicking on the moor, the good son, artist and friend, who wrote so many beautiful things. I am proud of him, and grateful for existence.”

Three years after Phillpotts’ death, his widow, lamenting that the estate was much too large for her and her housekeeper to maintain, sold Kerswell and its twenty acres of grounds (on which stood pleasure gardens, walled gardens, rose gardens, a stable block and a lodge). Five years later Robina passed away, at the age of seventy-eight. For several years Adelaide and Nicholas traveled happily around the world, in trips about which she gave account in her 1969 book Panorama of the World. By this time Nicholas tragically had passed away at the age of sixty, along with Jan, whom the lonely Adelaide had tried fruitlessly to contact after Nicholas’ death in 1967. Henry followed them into the great unknown in 1976, shortly before Professor Dayananda arrived from the United States to interview Adelaide about her famous father, whose reputation, truth be told, had fast faded since his death. “Having outlived all my loved ones, no one would be close to me again, and it was eerie for the first time to be quite alone,” Adelaide mournfully observed, though she relished reliving the distinguished past with the American academic who professed greatly to admire her father’s work.

In 1981 Adelaide at the age of eighty-five published her own fascinating Reverie, which sadly received little attention outside Devon, and not even that much within Devon, truth be told. Even her publisher, Robert Hale, failed to mention on the book jacket the shocking revelations about Adelaide’s incestuous relationship with her famous father, which one might have thought would have constituted the book’s greatest selling point. Adelaide survived another dozen years, publishing an occasional book, before finally passing away in the “picture postcard village” of Poughhill near Bude, having achieved nearly a century of life like her seemingly immortal father. Like him (only more so), Adelaide and her work faded into obscurity, an outcome which, in her case anyway, would probably not have surprised her modest soul.

But then how much public interest really remained in her father, for that matter, either as a writer or a man? Henry and Adelaide inherited a portion of their father’s vast literary estate (indicating that Eden late in life maintained some regard for his daughter), for, according to the Copyright Renewal Database, during 1969-70 the brother and sister renewed the American copyrights on the Phillpotts mysteries Ghostwater, Awake, Deborah!, A Deed with a Name and Flower of the Gods. (Adelaide during this time separately renewed Phillpotts’ fantastic adventure tale Tabletop.) For her part Robina renewed the American copyrights on the criminous Avis Bryden trilogy, of which her husband had thought rather highly, and the mysteries A Clue from the Stars, The Captain’s Curio, Mr. Digweed and Mr. Lumb and Portrait of a Scoundrel, along with the Regency adventure tale Minions of the Moon. (A year before his death Phillpotts himself had renewed the American copyright on his Twenties mystery A Voice from the Dark.)

Yet little was done to promote the Eden Phillpotts corpus of crime fiction in the English-speaking world in the years after his death. Forty-one years ago in 1982 Dover reprinted the author’s detective novel The Red Redmaynes, which Jacques Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor had praised as “a classic detective story that has never received due recognition,” in its well-produced vintage mystery paperback reprint series, easily making it the Phillpotts mystery of which modern readers are most aware. However, this volume today remains the sole quality Phillpotts mystery reprint in English of which I know, aside from Simon & Schuster imprint Prologue Books’ 2012 eBook reissue of the first Harrington Hext tale, Number 87.

In the 1970s and 1980s Barzun and Taylor highly praised much of Phillpotts’ crime corpus, but at the same time their influential nemesis Julian Symons summarily dismissed it. More recently I devoted one of my earliest posts at my blog The Passing Tramp to Phillpotts (“A Life of Crime 1: Eden Phillpotts,” 3 January 2013), with little impact, seemingly. I even posted at The Passing Tramp about Adelaide’s incest allegations (“Rather a Shocker,” 25 October 2014), but again I made little impression, apparently, aside from offending an anonymous commenter who was a great devotee of Eden Phillpotts mainstream fiction. (You can read our back and forth exchange in the comments to that post.) Mystery writer Martin Edwards declined to discuss Phillpotts in his Edgar Award winning 2015 book about the Detection Club, The Golden Age of Murder, despite Phillpotts’ connection to Agatha Christie and Edwards’ own inclusion of the prostitute scandal which embroiled Sir Basil Thomson, another vintage mystery writer who was not a member of the Detection Club. When I queried Martin over this, he replied that Adelaide’s allegations were unproven.

This, of course, was a few years before the dawn of “Me Too.” Certainly many today will not be inclined to challenge, or put another, more charitable construction upon, Adelaide’s claims about her father. In my view Adelaide makes an overwhelmingly compelling case against her father’s monstrous autocratic sway over her (and his household), one which is buttressed by the man’s own letters to her. Interestingly, another Phillpotts missive, written to an unnamed woman in 1927, when Mussolini was famously making the trains run on time in Italy and murdering his political opposition, expresses the author’s preference for benevolent despotism, believing as he does that

The masses have always needed a string to lead them. Take Italy & take England under the Commonwealth. You may regard dictatorship as in every sense reactionary; but weighed in the balance of national prosperity & increased well-being for the greater number, benevolent autocracy has a great deal to be said for it—given the men big enough to lead & powerful enough to impress their will on a nation & noble enough to act on high principles only.

Did Phillpotts in his overweening imagination see himself as a benevolent autocrat, imposing his highly-principled, noble will on his own little kingdom of lesser dependents? Eleven years after composing the above missive, the author, evidently disenchanted with dictators, in a short foreword to one of his books, the crime novel Portrait of a Scoundrel (1938), lectured to his readers, seemingly oblivious of his own domineering history:

Selfishness must always be an anti-social vice, promoting disunion and disharmony, but its impact varies. The average egoist merely represents waste of human material….His activities may injure nothing but his own self….But egomania, combined with great intellect and great will power, creates far more formidable evil, as the history of dictators and “spell-binders” fruitfully attests….

The publicity-shy Phillpotts once said, long before Adelaide ever dreamed of Reverie, that people would find him only in his work. Being a crime fiction devotee, as we know, I looked for answers to Eden in his mysteries. In his 1926 detective novel Jig-Saw, there is a character named Bella Brent, a “worthless” woman of thirty years (the same age, at the time of the book’s publication, as Adelaide), who defied and shamed her good-hearted father, finally descending into a life of sordid prostitution. She is one of the novel’s murder victims and no one misses her—indeed, the consensus from the other characters is that death was the best thing that could have happened to her. The author generously allows Bella’s killer to get off scot-free.

Many years later, in Phillpotts’ final detective novel, an odd, archaic sort of manners mystery entitled George and Georgina that he published a year after Adelaide’s defiant marriage, we learn that the narrating character, Georgina Gillespie, forty-eight year old twin sister to George, was long ago disinherited by her father for making a marriage of which he disapproved. Surely Phillpotts could not possibly have written the following words without thinking of his and Adelaide’s own melancholy recent history:

Unhappily, before his death, this famous man, Horace Gillespie, quarreled very bitterly with me in the sacred matter of my life’s future partner, and when Lord Felix Crystal won my passionate devotion and promise to become his wife, tragedy followed upon tragedy, for ferocious opposition confronted me….From being a kindly and generous parent who had educated me well, often taken me abroad with him…and was ever jealous for my happiness and comfort; after spoiling me no little and being proud of me in his way, poor father went to the opposite extreme and developed the most terrible enmity. He hated the match that I had arranged for myself and he loathed dear Felix…concentrating upon the superficial fact that my loved one’s financial position and prospects alike were deplorable and assuring me bluntly, even brutally, that not a penny of Gillespie money should ever be applied to mending them. But worship such as ours was proof against this monstrous attitude. Felix felt surprise and disappointment naturally, but allowed nothing to shake his devotion and I could not break my promise, nor my lover’s heart, for the sake of a mistaken father’s peace….my famous but foolish father…made a new will, casting me out….

All experience is grist to the author’s mill, for sure, but is there something of a regretful mea culpa here? Yet Phillpotts had eight more years to mend his willful folly with Adelaide and Nicholas, and he never did so.

Phillpotts’ defenders might well point out that Adelaide herself still expressed love for her famous father despite all of the terrible claims which she made about him, that she deemed him a great man and wanted him judged by his serious writing, not his sinful wages. The daughter’s love and respect for her father’s fiction comes through over and over again in the pages of Reverie. Like Agatha Christie, Adelaide proudly singled out for affectionate praise The Flint Heart, one of the few Phillpotts works that exists in a quality reprint edition today: “He dedicated to me a fairy story called The Flint Heart about the Pixies’ Holt near Dartmeet, a woodland glen where I had often played. How proud I was, and still am, of that charming and amusing book. With it he gave me a flint arrowhead set in gold as a brooch, which I wore constantly, until it was stolen in Spain.” (Declining to play favorites between his offspring in this case, the author in1903, partly drawing on the African experiences of his handsome, adventurous and short-lived middle brother Cecil, also had dedicated an earlier book, an H. Rider Haggard-esque African adventure saga entitled The Golden Fetich, to his son Henry.)

I respect Adelaide’s words, and accept that her relationship with her father was, well, complex, like human nature itself. “He was an epitome of human kind,” Adelaide observes, “a multifarious, compound being, capable of heights and depths, combining instinct and intellect, often at war with himself—a fusion of moral, immoral and amoral tendencies—a comprehensive, universal man, and a great artist, a genius. He would have told this story quite differently, from his point of view.” I agree with the daughter as well that Phillpotts was an astoundingly diverse and hugely talented writer. And yet—I find it hard to abandon Adelaide’s lyrical Reverie without darker memories of Eden Phillpotts, who, if her account is accurate, on many occasions over a half-century exercised his dominion over his daughter, like the most heartless of fathers in Victorian fiction, in an utterly cruel and capricious fashion, devastatingly cutting all ties with her completely when finally she dared to wed against his will, intolerably displacing him, as he saw it, in her deepest affections. Agatha Christie’s portly Victorian papa, Frederick Alvah Miller, may have been a dull and unexceptionable gentleman, more concerned with his digestion than fictive creation, who passed away when Agatha was eleven; yet, in resounding contrast with Eden Phillpotts, Fred Miller, however unmemorable, at least was no faunish, fearsome monster of egoism like the Man of Letters (however sublimely creative). Comparing Agatha Miller with her slightly younger neighbor Adelaide Phillpotts, one would have to conclude, I believe, that it was Agatha who was the child of fortune.

Appendix: The Crime, Adventure and Detective Novels of Eden Phillpotts

My Adventure in the Flying Scotsman (novella) (1888)

The End of a Life (1891)

A Tiger’s Cub (1895)

The Golden Fetich (1903)

The Sinews of War/Doubloons (1906) (with Arnold Bennett)

The Statue (1908) (with Arnold Bennett)

The Three Knaves (1912)

The Grey Room (1921)

Number 87 (1922) (Hext)

The Red Redmaynes (1922)

The Thing at Their Heels (1923) (Hext)

Who Killed Cock Robin?/Who Killed Diana? (1924) (Hext)

A Voice from the Dark (1925)

The Monster (1925) (Hext)

Jig-Saw/The Marylebone Miser (1926)

The Jury (1927)

Found Drowned (1931)

Bred in the Bone (1932) (Vol. 1, The Book of Avis)

A Clue from the Stars (1932)

The Captain’s Curio (1933)

Witch’s Cauldron (1933) (Vol. 2, The Book of Avis)

Mr. Digweed and Mr. Lumb (1933)

A Shadow Passes (1934) (Vol. 3, The Book of Avis)

Minions of the Moon (1934)

The Wife of Elias (1935)

Physician, Heal Thyself/The Anniversary Murder (1935)

A Close Call (1936)

Lycanthrope: The Mystery of Sir William Wolf (1937)

Portrait of a Scoundrel (1938)

Monkshood (1939)

Tabletop (1939)

Awake, Deborah! (1940)

Ghostwater (1941)

A Deed without a Name (1942)

Flower of the Gods (1943)

They Were Seven (1944)

The Drums of Dombali (1945)

The Fall of the House of Heron (1948)

George and Georgina (1952)