The Road to Aphex Twin’s “Selected Ambient Works Volume II” (original) (raw)

LISTS The Road to Aphex Twin’s “Selected Ambient Works Volume II” By Andy Beta · October 16, 2024

My decades-long obsession with Aphex Twin started with a mixtape (it was the early ‘90s after all). A friend needed something to fill the final two minutes of Side A and slotted in one of the untitled selections from the recently released monolith Selected Ambient Works Volume II. The work of British producer Richard D. James under his Aphex Twin alias, he was already known as a wunderkind of electronic music in the UK underground. But that didn’t always waft its way to the Texas suburbs where, as a teenager, I was a zealot for punk, grunge, hip-hop, and alternative. Hearing this brief interlude (an untitled track that iTunes now calls “White Blur” when loading a scratched copy into my computer) left me wholly perplexed.

Upon release, SAW II seemed like something that had crashed to Earth. The cover looked like the side of an alien ship, the cryptic insignia—in sepia tones burnished by solar radiation exposure—having weathered decades of galaxy travel to reach us. The blurry images inside the album were like snapshots from this distant planet. And the music itself was transformative. Haunting, forlorn, yet oddly poignant, it conjured subzero climes, poisonous atmospheres, and worlds where humans had never set foot. And yet, there was something irreducibly human about it all as well.

Somewhat brushed aside at the time (Simon Reynolds even called it “sombre [sic] and bleak […] more of his eerie sound-paintings and less of the naïve music-box melodies that won him so many devotees”), since then, SAW II has entered the canon of ambient music, serving as a gateway drug to other realms of electronic music for myself and many others. And in the decades that followed, a secret history of the album slowly came to light. That alien art cover? Well, that was just the side of a leather suitcase that Richard James had taken an X-ACTO blade to, etching his iconic logo into it. The unidentified photos that seemed like transmissions from an unknown world? Blurry close-up photos taken by his girlfriend around their London flat at the time.

His music is similarly earthbound. With the advent of computers and magnetic tape, pioneering post-war composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen, Tod Dockstader, and Steve Reich began to experiment with the interface between man and machination to head-swimming effect. And then there’s the chance-based work of iconic composer John Cage, who embraced accident and happenstance as key elements of his compositions. Muck about, live with the results, and get on with it seemed a key philosophy of James’s work during this fecund time period.

Just don’t try and slot him as the ambient heir of Brian Eno. While Eno named the concept with 1979’s Ambient 1 (Music For Airports), James insisted that those groundbreaking ambient albums had no bearing on his own excursions into these beat-less realms. “Music without beats has also been made for thousands of years, so there is actually nothing shocking going on,” he told OOR Magazine in 1996. “I was making that kind of music long before I heard an Eno and all that shit.”

Bearing this in mind, here’s an overview of the album’s lineage, as represented by precursors as well as parallels.

Forefathers

Karlheinz Stockhausen

The grandfather of modern electronic music, German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen was an early advocate for the use of computers in composition. Kontakte, his groundbreaking work from the late 1950s, melds sounds generated with radio, sine-wave generators, gramophone, and the like at the Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR), the legendary electronic-music studio in Cologne, to the live sounds of two instrumentalists playing percussion instruments. The mix between human players and electronic music has never felt more visceral and bracing. As James admitted to the Guardian back in 1994, he had spent most of the previous year listening to Stockhausen, whom he hadn’t previously heard before. “I like it, it’s totally mad,” he told the interviewer with a grin. You can hear how all of that seeps into _SAW II_’s soundscapes.

Tod Dockstader

An old Coke bottle, a nail, a marble, some deflated balloons, a few rolls of adhesive tape…in the hands of Tod Dockstader, these trivial items and certified junk all conspired to create masterworks of electronic music in the early 1960s, during the dawn of the electronic music genre, when the only people who could afford most of the pricey computer gear were firmly ensconced in the white towers of academia. Dockstader was and remained an outsider for most of his life. For 1964’s Quatermass, Dockstader carved down some 12 hours of tape—most of it the sound of a deflating balloon—into five movements conjuring drones, discernible laments, and other lurching rhythms. Hearing new worlds in old junk is a tenet of SAW II and Aphex Twin has long been an admirer of Dockstader’s example. As recently as 2023, Aphex Twin still drops Dockstader in his DJ sets.

Laurie Spiegel

Right now, Voyager 1 is some 15,000,000,000 miles and counting from Earth, whizzing through interstellar space. And onboard is the Golden Record containing a multitude of Earth sounds, one of which is composer Laurie Spiegel’s computerized realization of Johannes Kepler’s 1619 treatise Harmony of the Worlds. A Juilliard graduate who spent time at Bell Laboratories, Spiegel focused on programming over musical composition. But that doesn’t mean her 1980 album isn’t a wondrous listen. Meticulously crafted from sessions involving disk drives the size of washing machines to preserve mere seconds of code, Spiegel draws on her appreciation of music from Africa, Appalachia, and the Western classical canon to create this luminous computer music. And liner note details like, “This 32k DDP understood FORTRAN IV and DAP II 24-bit assembly language. It could do an integer add in as little as 3.8 milliseconds but a floating point multiply could take up to 115.9 microseconds,” no doubt sounded like music to the young programmer in James.

Michael O’Shea

“I used to spend all my time building the stuff, but now I haven’t built anything for ages,” James told one interviewer. “A lot of my stuff breaks down, so at the moment I’m just a technician repairing things I’ve built over the years.” Perhaps Richard D. James never encountered street busker Michael O’Shea, who was known to set up at Covent Garden in London’s West End, but as two iconoclasts pushing against Britain’s buttoned-up mentality and conjuring the sounds they could only hear in their heads as manifested on homemade instruments, they are kindred spirits.

O’Shea was a nomadic musician, traveling the world and teaching himself instruments along the way, such as sitar. But in his travels, he came across an old door and set about adding strings to the wood so as to craft something new. He called the thing “Mó Cará” (Gaelic for “my friend”) and strummed and thwacked its 17 strings with a pair of chopsticks, running it all through a battery of effects to create an otherworldly, mesmerizing sound. This album is the lone document of that enigma, captured when he popped into the studio with Wire’s Bruce Gilbert and Graham Lewis one day.

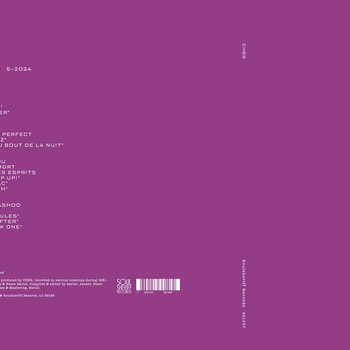

CHBB

. 00:10 / 00:58

. 00:10 / 00:58

While best known for their proto-industrial/electroclash/techno song “Los Niños del Parque” from 1984 (recorded as Liaisons Dangereuses), when DAF member Chrislo Haas and founding member of Einstürzende Neubauten Beate Bartel first hooked up as a couple and creative partnership, they used their gear to make raw trailblazing electronic music as CHBB. Not familiar with them? Well, no one was, as it was only issued on a series of self-released cassettes in 1981 in a ludicrously small edition of 50. Only heard in full this year, it presents a fascinating, previously isolated world of two lovers going deep into the circuitry of their gear and finding mysterious new sound realms within.

Contemporaries

Trans-4M

“Arrival” is of the most mysterious ambient house 12-inches from the early ‘90s. Which is a pity, as Belgian brothers Dimitri and Stefan van Elsen melted together ambient tropes (Indian sitar, hand drums, indigenous chants, punchline samples) with as much skill and daring as more popular acts like The Orb and Future Sound of London. But they also let in wandering saxophone, animal grunts, and some gorgeous piano on this singular album, thankfully reissued in 2019.

Silence

Hundreds of miles from James in London, a frustrated guitarist in Frankfurt, Germany, strumming his six-string along the banks of a river, had a similar epiphany about ambient that had nothing to do with Brian Eno. “My definition of ambient has nothing in common with Eno’s,” Pete Namlook told an interviewer. “It’s about a journey, about intense emotions.” This 1992 ambient effort revealed another aspect of what ambient music could be. Utilizing his synthesizer like the cello and bass section of an orchestra, Namlook allows dramatic motifs to rise and fall, while also weaving in field recordings of rain and hand drums. The album toggles between airy weightlessness and looming darkness.

Spacetime Continuum

By the time SAW II landed, San Franciscan producer Jonah Sharp was already exploring the deep reaches of inner space. His first release was a collaboration with famed ethnobotanist and ‘shroom-chewing shaman Terence McKenna, a soundtrack perfect for such exploration, but perhaps not much else. Ditching the didgeridoo and spoken word aspect, 1993’s Flurescence remains a groundbreaking early ambient electronic effort, moving from gurgles and flutters to bright acid techno by the last track.

Anthony Manning

In the summer of 1993, British producer Anthony Manning started mucking about with his Roland R-8 drum machine, a tricky device to program, for as Manning noted “[it] doesn’t allow you to assign a pitch to a note in the conventional sense…it assigns a numerical value.” Every single element of Islets in Pink Polypropylene was painstakingly crafted and charted on graph paper by hand and adjusted, so each track here took weeks to punch in. The end result was a lack of sleep for Manning, yet it might be the closest anyone else operating in London at the time got to conjuring the uncanny mix of frigidity and human warmth of SAW II. On its own merits, IiPP is a singular entry in the ambient electronic canon.

Sun Electric

One of the best groups to work in the ambient electronic idiom, Sun Electric’s legacy has been overshadowed somewhat by its members’ future endeavors (see Max Loderbauer’s duo with Ricardo Vilallobos and Thomas Fehlmann’s long tenure in the Orb). But on this live set from 1994, captured a mere four months after SAW II hit the shelves, Loderbauer and Tom Thiel (with Fehlmann credited as “Global Energy Consultant”) go into deep exploratory mode. The set oozes and sparkles like liquid gold across its three immersive tracks.