antibiotic resistance – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Using AI to Find New Antibiotics Still a Work in Progress

Posted on September 13th, 2022 by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Each year, more than 2.8 million people in the United States develop bacterial infections that don’t respond to treatment and sometimes turn life-threatening [1]. Their infections are antibiotic-resistant, meaning the bacteria have changed in ways that allow them to withstand our current widely used arsenal of antibiotics. It’s a serious and growing health-care problem here and around the world. To fight back, doctors desperately need new antibiotics, including novel classes of drugs that bacteria haven’t seen and developed ways to resist.

Developing new antibiotics, however, involves much time, research, and expense. It’s also fraught with false leads. That’s why some researchers have turned to harnessing the predictive power of artificial intelligence (AI) in hopes of selecting the most promising leads faster and with greater precision.

It’s a potentially paradigm-shifting development in drug discovery, and a recent NIH-funded study, published in the journal Molecular Systems Biology, demonstrates AI’s potential to streamline the process of selecting future antibiotics [2]. The results are also a bit sobering. They highlight the current limitations of one promising AI approach, showing that further refinement will still be needed to maximize its predictive capabilities.

These findings come from the lab of James Collins, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, and his recently launched Antibiotics-AI Project. His audacious goal is to develop seven new classes of antibiotics to treat seven of the world’s deadliest bacterial pathogens in just seven years. What makes this project so bold is that only two new classes of antibiotics have reached the market in the last 50 years!

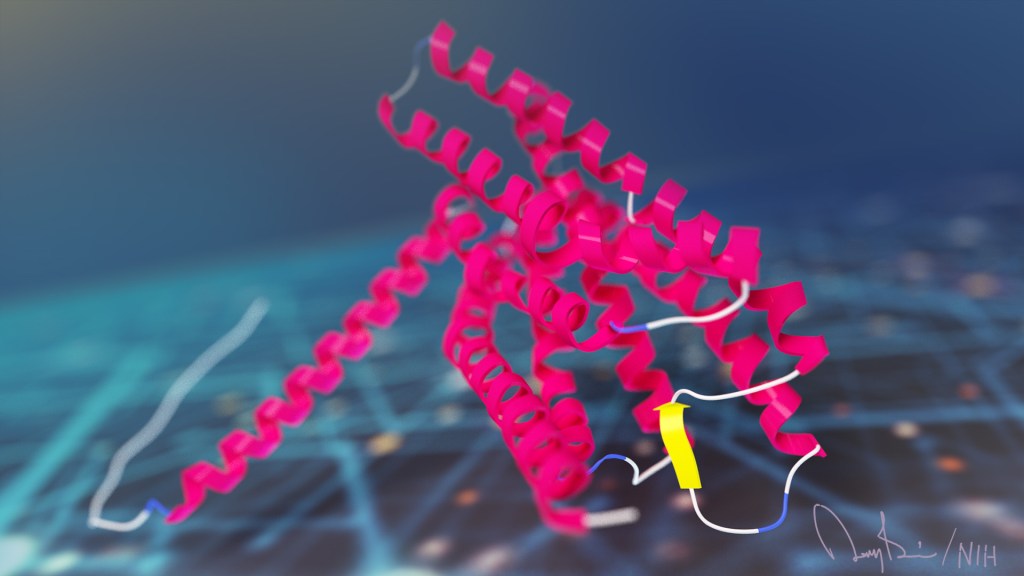

In the latest study, Collins and his team looked to an AI program called AlphaFold2 [3]. The name might ring a bell. AlphaFold’s AI-powered ability to predict protein structures was a finalist in _Science Magazine_’s 2020 Breakthrough of the Year. In fact, AlphaFold has been used already to predict the structures of more than 200 million proteins, or almost every known protein on the planet [4].

AlphaFold employs a deep learning approach that can predict most protein structures from their amino acid sequences about as well as more costly and time-consuming protein-mapping techniques.

In the deep learning models used to predict protein structure, computers are “trained” on existing data. As computers “learn” to understand complex relationships within the training material, they develop a model that can then be applied for making predictions of 3D protein structures from linear amino acid sequences without relying on new experiments in the lab.

Collins and his team hoped to combine AlphaFold with computer simulations commonly used in drug discovery as a way to predict interactions between essential bacterial proteins and antibacterial compounds. If it worked, researchers could then conduct virtual rapid screens of millions of new synthetic drug compounds targeting key bacterial proteins that existing antibiotics don’t. It would also enable the rapid development of antibiotics that work in novel ways, exactly what doctors need to treat antibiotic-resistant infections.

To test the strategy, Collins and his team focused first on the predicted structures of 296 essential proteins from the Escherichia coli bacterium as well as 218 antibacterial compounds. Their computer simulations then predicted how strongly any two molecules (essential protein and antibacterial) would bind together based on their shapes and physical properties.

It turned out that screening many antibacterial compounds against many potential targets in E. coli led to inaccurate predictions. For example, when comparing their computational predictions with actual interactions for 12 essential proteins measured in the lab, they found that their simulated model had about a 50:50 chance of being right. In other words, it couldn’t identify true interactions between drugs and proteins any better than random guessing.

They suspect one reason for their model’s poor performance is that the protein structures used to train the computer are fixed, not flexible and shifting physical configurations as happens in real life. To improve their success rate, they ran their predictions through additional machine-learning models that had been trained on data to help them “learn” how proteins and other molecules reconfigure themselves and interact. While this souped-up model got somewhat better results, the researchers report that they still aren’t good enough to identify promising new drugs and their protein targets.

What now? In future studies, the Collins lab will continue to incorporate and train the computers on even more biochemical and biophysical data to help with the predictive process. That’s why this study should be interpreted as an interim progress report on an area of science that will only get better with time.

But it’s also a sobering reminder that the quest to find new classes of antibiotics won’t be easy—even when aided by powerful AI approaches. We certainly aren’t there yet, but I’m confident that we will get there to give doctors new therapeutic weapons and turn back the rise in antibiotic-resistant infections.

References:

[1] 2019 Antibiotic resistance threats report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[2] Benchmarking AlphaFold-enabled molecular docking predictions for antibiotic discovery. Wong F, Krishnan A, Zheng EJ, Stark H, Manson AL, Earl AM, Jaakkola T, Collins JJ. Molecular Systems Biology. 2022 Sept 6. 18: e11081.

[3] Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Kavukcuoglu K, Kohli P, Hassabis D., et al. Nature. 2021 Aug;596(7873):583-589.

[4] ‘The entire protein universe’: AI predicts shape of nearly every known protein. Callaway E. Nature. 2022 Aug;608(7921):15-16.

Links:

Antimicrobial (Drug) Resistance (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

Collins Lab (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge)

The Antibiotics-AI Project, The Audacious Project (TED)

AlphaFold (Deep Mind, London, United Kingdom)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of General Medical Sciences

Posted In: News

Tags: AI, AlphaFold, antibiotic resistance, antibiotics, Antibiotics-AI Project, artificial intelligence, bacteria, bacterial infections, Breakthrough of the Year, computer simulation, deep learning, drug discovery, E. coli, machine learning, structural biology, synthetic biology

Some ‘Hospital-Acquired’ Infections Traced to Patient’s Own Microbiome

Posted on October 23rd, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

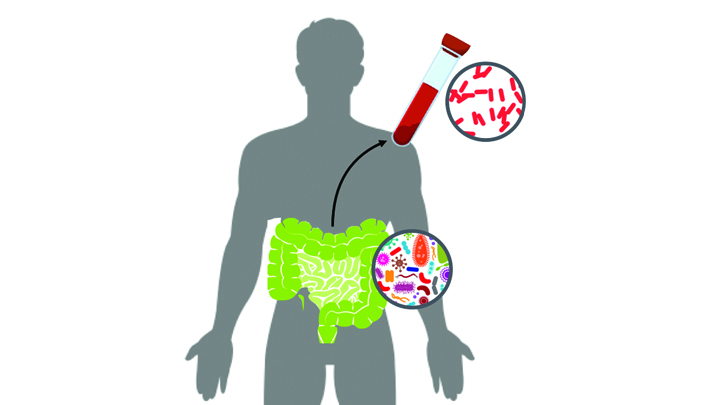

Caption: New computational tool determines whether a gut microbe is the source of a hospital-acquired bloodstream infection

Credit: Fiona Tamburini, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA

While being cared for in the hospital, a disturbingly large number of people develop potentially life-threatening bloodstream infections. It’s been thought that most of the blame lies with microbes lurking on medical equipment, health-care professionals, or other patients and visitors. And certainly that is often true. But now an NIH-funded team has discovered that a significant fraction of these “hospital-acquired” infections may actually stem from a quite different source: the patient’s own body.

In a study of 30 bone-marrow transplant patients suffering from bloodstream infections, researchers used a newly developed computational tool called StrainSifter to match microbial DNA from close to one-third of the infections to bugs already living in the patients’ large intestines [1]. In contrast, the researchers found little DNA evidence to support the notion that such microbes were being passed around among patients.

Posted In: News

Tags: antibiotic resistance, bacteria, bloodstream infections, bone marrow transplantation, computational biology, E. coli, genomics, gut microbiome, healthcare delivery, hospital, hospital acquired infections, immunocompromised, infection, Klebsiella pneumonia, microbial imbalance, microbiology, microbiome, pneumonia, stool sample, StrainSifter, urinary tract infection

A Bacterium Reaches Out and Grabs Some New DNA

Posted on July 19th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: Dalia Lab, Indiana University, Bloomington

If you like comic book heroes, you’ll love this action-packed video of a microbe with a superpower reminiscent of a miniature Spiderman. Here, for the first time ever, scientists have captured in real-time—and in very cool detail—the important mechanism of horizontal gene transfer in bacteria.

Specifically, you see Vibrio cholerae, the water-dwelling bacterium that causes cholera, stretching out a hair-like appendage called a pilus (green) to snag a free snippet of DNA (red). After grabbing the DNA, V. cholerae swiftly retracts the pilus, threading the DNA fragment through a pore on the cell surface for stitching into its genome.

Powerful Antibiotics Found in Dirt

Posted on February 20th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Researchers found a new class of antibiotics in a collection of about 2,000 soil samples.

Credit: Sean Brady, The Rockefeller University, New York City

Many of us think of soil as lifeless dirt. But, in fact, soil is teeming with a rich array of life: microbial life. And some of those tiny, dirt-dwelling microorganisms—bacteria that produce antibiotic compounds that are highly toxic to other bacteria—may provide us with valuable leads for developing the new drugs we so urgently need to fight antibiotic-resistant infections.

Recently, NIH-funded researchers discovered a new class of antibiotics, called malacidins, by analyzing the DNA of the bacteria living in more than 2,000 soil samples, including many sent by citizen scientists living all across the United States [1]. While more work is needed before malacidins can be tried in humans, the compounds successfully killed several types of multidrug-resistant bacteria in laboratory tests. Most impressive was the ability of malacadins to wipe out methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) skin infections in rats. Often referred to as a “super bug,” MRSA threatens the lives of tens of thousands of Americans each year [2].

Posted In: Health, Science, technology

Tags: antibiotic resistance, antibiotic treatment, antibiotics, bacteria, calcium-dependent antibiotics, citizen science, DNA, Drugs from Dirt, malacidins, MRSA, multi-drug resistance, multidrug resistant bacteria, soil, soil-dwelling bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptomyces albus, super bug

Creative Minds: Rapid Testing for Antibiotic Resistance

Posted on June 22nd, 2017 by Dr. Francis Collins

Ahmad (Mo) Khalil

The term “freeze-dried” may bring to mind those handy MREs (Meals Ready to Eat) consumed by legions of soldiers, astronauts, and outdoor adventurers. But if one young innovator has his way, a test that features freeze-dried biosensors may soon be a key ally in our nation’s ongoing campaign against the very serious threat of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

Each year, antibiotic-resistant infections account for more than 23,000 deaths in the United States. To help tackle this challenge, Ahmad (Mo) Khalil, a researcher at Boston University, recently received an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award to develop a system that can more quickly determine whether a patient’s bacterial infection will respond best to antibiotic X or antibiotic Y—or, if the infection is actually viral rather than bacterial, no antibiotics are needed at all.

Tags: 2016 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, antibiotic overuse, antibiotic resistance, antibiotic-resistant infections, antibiotics, bacteria, biosensor, diagnostics, drug resistance, genomics, infections, point-of-care diagnostics, RNA sensor tests, RNA sensors, synthetic biology, transcriptome

Snapshots of Life: Fighting Urinary Tract Infections

Posted on May 25th, 2017 by Dr. Francis Collins

Source: Valerie O’Brien, Matthew Joens, Scott J. Hultgren, James A.J. Fitzpatrick, Washington University, St. Louis

For patients who’ve succeeded in knocking out a bad urinary tract infection (UTI) with antibiotic treatment, it’s frustrating to have that uncomfortable burning sensation flare back up. Researchers are hopeful that this striking work of science and art can help them better understand why severe UTIs leave people at greater risk of subsequent infection, as well as find ways to stop the vicious cycle.

Here you see the bladder (blue) of a laboratory mouse that was re-infected 24 hours earlier with the bacterium Escherichia coli (pink), a common cause of UTIs. White blood cells (yellow) reach out with what appear to be stringy extracellular traps to immobilize and kill the bacteria.

Tags: antibiotic resistance, bladder, bladder infection, chronic inflammation, Cox2, E. coli, Escherichia coli, FASEB Bioart 2016, immunology, inflammation, microbiology, recurrent UTI, urinary tract infection, UTI, white blood cells, women's health

Fighting Parasitic Infections: Promise in Cyclic Peptides

Posted on April 11th, 2017 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Cyclic peptide (middle) binds to iPGM (blue).

Credit: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH

When you think of the causes of infectious diseases, what first comes to mind are probably viruses and bacteria. But parasites are another important source of devastating infection, especially in the developing world. Now, NIH researchers and their collaborators have discovered a new kind of treatment that holds promise for fighting parasitic roundworms. A bonus of this result is that this same treatment might work also for certain deadly kinds of bacteria.

The researchers identified the potential new therapeutic after testing more than a trillion small protein fragments, called cyclic peptides, to find one that could disable a vital enzyme in the disease-causing organisms, but leave similar enzymes in humans unscathed. Not only does this discovery raise hope for better treatments for many parasitic and bacterial diseases, it highlights the value of screening peptides in the search for ways to treat conditions that do not respond well—or have stopped responding—to more traditional chemical drug compounds.

Tags: anthrax, antibiotic resistance, Bacillus anthracis, bacteria, cell biology, chemistry, cofactor-independent phosphoglycerate mutase, cyclic peptides, drug design, drug development, drug discovery, drug targets, drugs, glycolysis, ipglycermides, iPGM, parasite, peptide, roundworm, small molecules, Staphylococcus aureus

Gene Expression Test Aims to Reduce Antibiotic Overuse

Posted on February 2nd, 2016 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Duke physician-scientist Ephraim Tsalik assesses a patient for a respiratory infection.

Credit: Shawn Rocco/Duke Health

Without doubt, antibiotic drugs have saved hundreds of millions of lives from bacterial infections that would have otherwise been fatal. But their inappropriate use has led to the rise of antibiotic-resistant superbugs, which now infect at least 2 million Americans every year and are responsible for thousands of deaths [1]. I’ve just come from the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, where concerns about antibiotic resistance and overuse was a topic of conversation. In fact, some of the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies issued a joint declaration at the forum, calling on governments and industry to work together to combat this growing public health threat [2].

Many people who go to the doctor suffering from respiratory symptoms expect to be given a prescription for antibiotics. Not only do such antibiotics often fail to help, they serve to fuel the development of antibiotic-resistant superbugs [3]. That’s because antibiotics are only useful in treating respiratory illnesses caused by bacteria, and have no impact on those caused by viruses (which are frequent in the wintertime). So, I’m pleased to report that a research team, partially supported by NIH, recently made progress toward a simple blood test that analyzes patterns of gene expression to determine if a patient’s respiratory symptoms likely stem from a bacterial infection, viral infection, or no infection at all.

In contrast to standard tests that look for signs of a specific infectious agent—respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or the influenza virus, for instance—the new strategy casts a wide net that takes into account changes in the patterns of gene expression in the bloodstream, which differ depending on whether a person is fighting off a bacterial or a viral infection. As reported in Science Translational Medicine [4], Geoffrey Ginsburg, Christopher Woods, and Ephraim Tsalik of Duke University’s Center for Applied Genomics and Precision Medicine, Durham, NC, and their colleagues collected blood samples from 273 people who came to the emergency room (ER) with signs of acute respiratory illness. Standard diagnostic tests showed that 70 patients arrived in the ER with bacterial infections and 115 were battling viruses. Another 88 patients had no signs of infection, with symptoms traced instead to other health conditions.

Tags: acute respiratory illness, Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group, antibiotic overuse, antibiotic resistance, antibiotic-resistant infections, antibiotics, applied genomics, bacteria, bacterial infections, blood test, diagnostics, gene expression signature, gene signature, genomics, immunology, infectious disease, noninfectious respiratory problems, precision medicine, procalcitonin, respiratory bacteria, respiratory diseases, respiratory viruses, superbugs, Task Force for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria, virology, viruses

Creative Minds: Searching for Solutions to Chronic Infection

Posted on September 22nd, 2015 by Dr. Francis Collins

Kyle R. Allison

If you or a loved one has ever struggled with a bacterial infection that seemed to have gone away with antibiotic treatment, but then came back again, you’ll probably be interested to learn about the work of Kyle Allison. What sometimes happens when a person has an infection—for instance, a staph infection of the skin—is that antibiotics kill off the vast majority of bacteria, but a small fraction remain alive. After antibiotic treatment ends, those lurking bacterial “persisters” begin to multiply, and the person develops a chronic infection that may be very difficult and costly to eliminate.

Unlike antibiotic-resistant superbugs, bacterial persisters don’t possess any specific genetic mutations that protect them against the killing power of one particular medication or another. Rather, the survival of these bacteria depends upon their ability to enter a dormant state that allows them to hang on in the face of antibiotic treatment. It isn’t clear exactly how the bugs do it, and that’s where Kyle’s work comes in.

Tags: antibiotic resistance, antibiotics, bacteria, bacterial persisters, chronic infections, dormant state, E. coli, Early Independence Award, Escherichia coli, infections, staph, Staphylococcus areus, systems biology

New Strategies in Battle Against Antibiotic Resistance

Posted on September 18th, 2014 by Drs. Anthony S. Fauci and Francis S. Collins

Caption: Colorized scanning-electron micrograph showing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae interacting with a human white blood cell.

Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

Over the past year, the problem of antibiotic resistance has received considerable attention, with concerns being raised by scientists, clinicians, public health officials, and many others around the globe. These bacteria are found not only in hospitals, but in a wide range of community settings. In the United States alone, antibiotic-resistant bacteria cause roughly 2 million infections per year, and 23,000 deaths [1].

In light of such daunting statistics, the need for action at the highest levels is clear, as is demonstrated by an Executive Order issued today by the President. Fighting antibiotic resistance is both a public health and national security priority. The White House has joined together with leaders from government, academia, and public health to create a multi-pronged approach to combat antibiotic resistance. Two high-level reports released today—the White House’s National Strategy for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (CARB) and the complementary President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) Report to the President on Combating Antibiotic Resistance—outline a series of bold steps aimed at addressing this growing public health threat.

Tags: Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group, antibiotic resistance, antibiotics, bacteria, CARB, clinical trials, diagnostics, DNA sequencing, drug development, Klebsiella pneumoniae, microbes, MRSA, National Database of Resistant Pathogens, National Strategy for Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria, open access, point-of-care tests, Prize, pulsed gel field electrophoresis, superbugs, surveillance, treatment, vaccines