fibrosis – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Healing Switch Links Acute Kidney Injury to Fibrosis, Suggesting Way to Protect Kidney Function

Posted on March 7th, 2024 by Dr. Monica M. Bertagnolli

The protein Sox9 switches on after kidney injury, then back off after repair. When healing doesn’t proceed optimally, Sox9 stays on, leading to scarring and fibrosis. Credit: Donny Bliss/NIH

Healthy kidneys—part of the urinary tract—remove waste and help balance chemicals and fluids in the body. However, our kidneys have a limited ability to regenerate healthy tissue after sustaining injuries from conditions such as diabetes or high blood pressure. Injured kidneys are often left with a mix of healthy and scarred tissue, or fibrosis, which over time can compromise their function and lead to chronic kidney disease or complete kidney failure. More than one in seven adults in the U.S. are estimated to have chronic kidney disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, most without knowing it.

Now, a team of researchers led by Sanjeev Kumar at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, has identified a key molecular “switch” that determines whether injured kidney tissue will heal or develop those damaging scars.1 Their findings, reported in the journal Science, could lead to new and less invasive ways to detect fibrosis in the kidneys. The research could also point toward a targeted therapeutic approach that might prevent or reverse scarring to protect kidney function.

In earlier studies, the research team found that a protein called Sox9 plays an important role in switching on the repair response in kidneys after acute injury.2 In some cases, the researchers noticed that Sox9 remained active for a prolonged period of a month or more. They suspected this might be a sign of unresolved injury and repair.

By conducting studies using animal models of kidney damage, the researchers found that cells that turned Sox9 on and then back off healed without fibrosis. However, cells that failed to regenerate healthy kidney cells kept Sox9 on indefinitely, which in turn led to the production of fibrosis and scarring.

According to Kumar, Sox9 appears to act like a sensor, switching on after injury. Once restored to health, Sox9 switches back off. When healing doesn’t proceed optimally, Sox9 stays on, leading to scarring. Importantly, the researchers also found they could encourage kidneys to recover by forcing Sox9 to turn off a week after an injury, suggesting it may be a promising drug target.

The researchers also looked for evidence of this process in human patients who have received kidney transplants. They could see that, when transplanted kidneys took longer to start working, Sox9 was switched on. Those whose kidneys continued to produce Sox9 also had lower kidney function and more scarring compared to those who didn’t.

The findings suggest that the dynamics observed in animal studies may be clinically relevant in people, and that treatments targeting Sox9 might promote kidneys to heal instead of scarring. The researchers say they hope that similar studies in the future will lead to greater understanding of healing and fibrosis in other organs—including the heart, lungs, and liver—with potentially important clinical implications.

References:

[1] Aggarwal S, et al. SOX9 switch links regeneration to fibrosis at the single-cell level in mammalian kidneys. Science. DOI: 10.1126/science.add6371 (2024).

[2] Kumar S, et al. Sox9 Activation Highlights a Cellular Pathway of Renal Repair in the Acutely Injured Mammalian Kidney. Cell Reports. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.034 (2015).

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

How to Heal Skin Without the Scars

Posted on July 15th, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: ZEISS Microscopy and Getty Images

Most of us can point to a few unwanted scars on our bodies. Every scar tells a story, but people are spending billions of dollars each year trying to hide or get rid of them [1]. What if there was a way to get the wounds on our skin to heal without scarring in the first place?

In a recent paper in the journal Science, a team of NIH-supported researchers has taken an important step in this direction. Working with mice, the researchers deciphered some of the key chemical and physical signals that cause certain skin cells to form tough, fibrous scars while healing a wound [2]. They also discovered how to reprogram them with a topical treatment and respond to injuries more like fetal skin cells, which can patch up wounds in full, regrowing hair, glands, and accessory structures of the skin, and all without leaving a mark.

Of course, mice are not humans. Follow-up research is underway to replicate these findings in larger mammals with skin that’s tighter and more akin to ours. But if the preclinical data hold up, the researchers say they can test in future human clinical trials the anti-scarring drug used in the latest study, which has been commercially available for two decades to treat blood vessel disorders in the eye.

The work comes from Michael Longaker, Shamik Mascharak, and colleagues, Stanford Medicine, Palo Alto, CA. But, to be more precise, the work began with a research project that Longaker was given back in 1987, while a post doc in the lab of Michael Harrison, University of California, San Francisco.

Harrison, a surgeon then performing groundbreaking prenatal surgery, noticed that babies born after undergoing surgery in the womb healed from their surgeries without any scarring. He asked his postdoc to find out why, and Longaker has been trying to answer that question and understand scar formation ever since.

Longaker and his Stanford colleague Geoffrey Gurtner suspected that the difference between healing inside and outside the womb had something to do with tension. Inside the womb, the skin of the unborn is bathed in fluid and develops in a soft, tension-free state. Outside the womb, human skin is exposed to continuous environmental stresses and must continuously remodel and grow to remain viable, which creates a high level of skin tension.

Following up on Longaker and Gurtner’s suspicion, Mascharak found in a series of mouse experiments that a particular class of fibroblast, a type of cell in skin and other connective tissues, activates a gene called Engrailed-1 during scar formation [3]. To see if mechanical stress played a role in this process, Mascharak and team grew mouse fibroblast cells on either a soft, stress-free gel or on a stiff plastic dish that produced mechanical strain. Importantly, they also tried growing the fibroblasts on the same strain-inducing plastic, but in the presence of a chemical that blocked the mechanical-strain signal.

Their studies showed that fibroblasts grown on the tension-free gel didn’t activate the scar-associated genetic program, unlike fibroblasts growing on the stress-inducing plastic. With the chemical that blocked the cells’ ability to sense the mechanical strain, Engrailed-1 didn’t get switched on either.

They also showed the opposite. When tension was applied to healing surgical incisions in mice, it led to an increase in the number of those fibroblast cells expressing Engrailed-1 and thicker scars.

The researchers went on to make another critical finding. The mechanical stress of a fresh injury turns on a genetic program that leads to scar formation, and that program gets switched on through another protein called Yes-associated protein (YAP). When they blocked this protein with an existing eye drug called verteporfin, skin healed more slowly but without any hint of a scar.

It’s worth noting that scars aren’t just a cosmetic issue. Scars differ from unwounded skin in many ways. They lack hair follicles, glands that produce oil and sweat, and nerves for sensing pain or pressure. Because the fibers that make up scar tissue run parallel to each other instead of being more intricately interwoven, scars also lack the flexibility and strength of healthy skin.

These new findings therefore suggest it may one day be possible to allow wounds to heal without compromising the integrity of the skin. The findings also may have implications for many other medical afflictions that involve scarring, such as liver and lung fibrosis, burns, scleroderma, and scarring of heart tissue after a heart attack. That’s also quite a testament to sticking with a good postdoc project, wherever it may lead. One day, it may even improve public health!

References:

[1] Human skin wounds: A major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Wound Repair Regen. 2009 Nov-Dec;17(6):763-771.

[2] Preventing Engrailed-1 activation in fibroblasts yields wound regeneration without scarring.

Mascharak S, desJardins-Park HE, Davitt MF, Griffin M, Borrelli MR, Moore AL, Chen K, Duoto B, Chinta M, Foster DS, Shen AH, Januszyk M, Kwon SH, Wernig G, Wan DC, Lorenz HP, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. Science. 2021 Apr 23;372(6540):eaba2374.

[3] Skin fibrosis. Identification and isolation of a dermal lineage with intrinsic fibrogenic potential. Rinkevich Y, Walmsley GG, Hu MS, Maan ZN, Newman AM, Drukker M, Januszyk M, Krampitz GW, Gurtner GC, Lorenz HP, Weissman IL, Longaker MT. Science. 2015 Apr 17;348(6232):aaa2151.

Links:

Skin Health (National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/NIH)

Scleroderma (NIAMS)

Michael Longaker (Stanford Medicine, Palo Alto, CA)

Geoffrey Gurtner (Stanford Medicine)

NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Posted In: News

Tags: burns, connective tissue, Engrailed-1, fibroblasts, fibrosis, mouse, scars, scleroderma, skin, tissue regeneration, verteporfin, wound healing, wounds, Yes-associated protein

Mapping Severe COVID-19 in the Lungs at Single-Cell Resolution

Posted on April 13th, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Image shows macrophages (red), fibroblast cells (green), and other cells (blue). In late COVID-19, macrophages migrate near fibroblasts, which may play a role in fibrosis. Credit: Images courtesy of André Rendeiro

A crucial question for COVID-19 researchers is what causes progression of the initial infection, leading to life-threatening respiratory illness. A good place to look for clues is in the lungs of those COVID-19 patients who’ve tragically lost their lives to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), in which fluid and cellular infiltrates build up in the lung’s air sacs, called alveoli, keeping them from exchanging oxygen with the bloodstream.

As shown above, a team of NIH-funded researchers has done just that, capturing changes in the lungs over the course of a COVID-19 infection at unprecedented, single-cell resolution. These imaging data add evidence that SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, primarily infects cells at the surface of the air sacs. Their findings also offer valuable clues for treating the most severe consequences of COVID-19, suggesting that a certain type of scavenging immune cell might be driving the widespread lung inflammation that leads to ARDS.

The findings, published in Nature [1], come from Olivier Elemento and Robert E. Schwartz, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York. They already knew from earlier COVID-19 studies about the body’s own immune response causing the lung inflammation that leads to ARDS. What was missing was an understanding of the precise interplay between immune cells and lung tissue infected with SARS-CoV-2. It also wasn’t clear how the ARDS seen with COVID-19 compared to the ARDS seen in other serious respiratory diseases, including influenza and bacterial pneumonia.

Traditional tissue analysis uses chemical stains or tagged antibodies to label certain proteins and visualize important features in autopsied human tissues. But using these older techniques, it isn’t possible to capture more than a few such proteins at once. To get a more finely detailed view, the researchers used a more advanced technology called imaging mass cytometry [2].

This approach uses a collection of lanthanide metal-tagged antibodies to label simultaneously dozens of molecular markers on cells within tissues. Next, a special laser scans the labeled tissue sections, which vaporizes the heavy metal tags. As the metals are vaporized, their distinct signatures are detected in a mass spectrometer along with their spatial position relative to the laser. The technique makes it possible to map precisely where a diversity of distinct cell types is located in a tissue sample with respect to one another.

In the new study, the researchers applied the method to 19 lung tissue samples from patients who had died of severe COVID-19, acute bacterial pneumonia, or bacterial or influenza-related ARDS. They included 36 markers to differentiate various types of lung and immune cells as well as the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and molecular signs of immune activation, inflammation, and cell death. For comparison, they also mapped four lung tissue samples from people who had died without lung disease.

Altogether, they captured more than 200 lung tissue maps, representing more than 660,000 cells across all the tissues sampled. Those images showed in all cases that respiratory infection led to a thickening of the walls surrounding alveoli as immune cells entered. They also showed an increase in cell death in infected compared to healthy lungs.

Their maps suggest that what happens in the lungs of COVID-19 patients who die with ARDS isn’t entirely unique. It’s similar to what happens in the lungs of those with other life-threatening respiratory infections who also die with ARDS.

They did, however, reveal a potentially prominent role in COVID-19 for white blood cells called macrophages. The results showed that macrophages are much more abundant in the lungs of severe COVID-19 patients compared to other lung infections.

In late COVID-19, macrophages also increase in the walls of alveoli, where they interact with lung cells known as fibroblasts. This suggests these interactions may play a role in the buildup of damaging fibrous tissue, or scarring, in the alveoli that tends to be seen in severe COVID-19 respiratory infections.

While the virus initiates this life-threatening damage, its progression may not depend on the persistence of the virus, but on an overreaction of the immune system. This may explain why immunomodulatory treatments like dexamethasone can provide benefit to the sickest patients with COVID-19. To learn even more, the researchers are making their data and maps available as a resource for scientists around the world who are busily working to understand this devastating illness and help put an end to the terrible toll caused by this pandemic.

References:

[1] The spatial landscape of lung pathology during COVID-19 progression. Rendeiro AF, Ravichandran H, Bram Y, Chandar V, Kim J, Meydan C, Park J, Foox J, Hether T, Warren S, Kim Y, Reeves J, Salvatore S, Mason CE, Swanson EC, Borczuk AC, Elemento O, Schwartz RE. Nature. 2021 Mar 29.

[2] Mass cytometry imaging for the study of human diseases-applications and data analysis strategies. Baharlou H, Canete NP, Cunningham AL, Harman AN, Patrick E. Front Immunol. 2019 Nov 14;10:2657.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

Elemento Lab (Weill Cornell Medicine, New York)

Schwartz Lab (Weill Cornell Medicine)

NIH Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Cancer Institute

Posted In: News

Tags: acute respiratory distress syndrome, alveoli, ARDS, bacterial pneumonia, COVID-19, COVID-19 immune response, dexamethasone, fibroblasts, fibrosis, imaging mass cytometry, lung inflammation, lung pathology, lung tissue map, lungs, macrophages, novel coronavirus, pandemic, respiratory diseases, SARS-CoV-2, single-cell resolution, spike protein

Tackling Fibrosis with Synthetic Materials

Posted on February 20th, 2020 by Dr. Francis Collins

April Kloxin/Credit: Evan Krape, University of Delaware, Newark

When injury strikes a limb or an organ, our bodies usually heal quickly and correctly. But for some people, the healing process doesn’t shut down properly, leading to excess fibrous tissue, scarring, and potentially life-threatening organ damage.

This permanent scarring, known as fibrosis, can occur in almost every tissue of the body, including the heart and lungs. With support from a 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, April Kloxin is applying her expertise in materials science and bioengineering to build sophisticated fibrosis-in-a-dish models for unraveling this complex process in her lab at the University of Delaware, Newark.

Though Kloxin is interested in all forms of fibrosis, she’s focusing first on the incurable and often-fatal lung condition called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). This condition, characterized by largely unexplained thickening and stiffening of lung tissue, is diagnosed in about 50,000 people each year in the United States.

IPF remains poorly understood, in part because it often is diagnosed when the disease is already well advanced. Kloxin hopes to turn back the clock and start to understand the disease at an earlier stage, when interventions might be more successful. The key is to develop a model that better recapitulates the complexity and irreversibility of the disease process in people.

Building that better model starts with simulating the meshwork of collagen and other proteins in the extracellular matrix (ECM) that undergird every tissue and organ in the body. The ECM’s interactions with our cells are essential in wound healing and, when things go wrong, also in causing fibrosis.

Kloxin will build three-dimensional hydrogels, crosslinked sponge-like networks of polymers, peptides, and proteins, with structures that more accurately capture the biological complexities of human tissues, including the ECMs within fibrous collagen-rich microenvironments. Her synthetic matrices can be triggered with light to lock in place and stiffen. The matrices also will make it possible to culture the lung’s epithelium, or outermost layer of cells, and connective tissue that surrounds it, to study cellular responses as the model shifts from a healthy and flexible to a stiffened, disease-like state.

Kloxin and her team will also integrate into their model system lung cells that have been engineered to fluoresce or light up under a microscope when the wound-healing program activates. Such fluorescent reporters will allow her team to watch for the first time how different cells and their nearby microenvironment respond as the composition of the ECM changes and stiffens. With this system, she’ll also be able to search for small molecules with the ability to turn off excessive wound healing.

The hope is that what’s learned with her New Innovator Award will lead to fresh insights and ultimately new treatments for this mysterious, hard-to-treat condition. But the benefits could be even more wide-ranging. Kloxin thinks that her findings will have implications for the prevention and treatment of other fibrotic diseases as well.

Links:

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

April Kloxin Group (University of Delaware, Newark)

Kloxin Project Information (NIH RePORTER)

NIH Director’s New Innovator Award (Common Fund)

NIH Support: Common Fund; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Posted In: Creative Minds

Tags: 2019 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award, bioengineering, collagen, ECM, extracellular matrix, fibrosis, hydrogel, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, IPF, lung epithelium, lungs, materials science, rare disease, tissue engineering, tissue microenvironment, wound healing

Can Organoids Yield Answers to Fatty Liver Disease?

Posted on June 4th, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

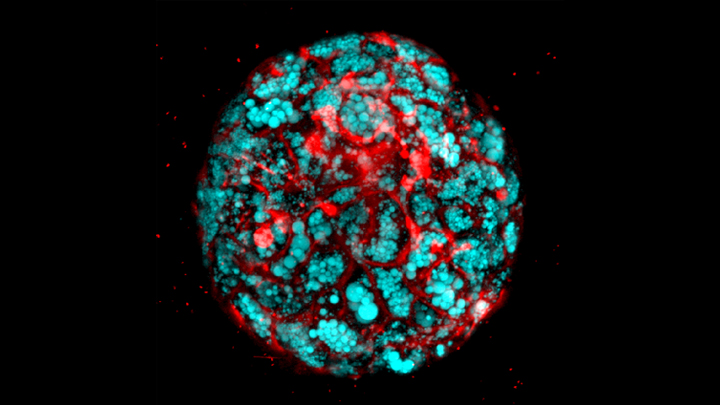

Confocal microscope image shows liver organoid made from iPS cells derived from children with Wolman disease. The hepatocyte cells (red) accumulate fat (blue). Credit: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

With advances in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology, it’s now possible to reprogram adult skin or blood cells to form miniature human organs in a lab dish. While these “organoids” closely mimic the structures of the liver and other vital organs, it’s been tough to get them to represent inflammation, fibrosis, fat accumulation, and many other complex features of disease.

Fatty liver diseases are an increasingly serious health problem. So, I’m pleased to report that, for the first time, researchers have found a reliable way to make organoids that display the hallmarks of those conditions. This “liver in a dish” model will enable the identification and preclinical testing of promising drug targets, helping to accelerate discovery and development of effective new treatments.

Previous methods working with stem cells have yielded liver organoids consisting primarily of epithelial cells, or hepatocytes, which comprise most of the organ. Missing were other key cell types involved in the inflammatory response to fatty liver diseases.

To create a better organoid, the team led by Takanori Takebe, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, focused its effort on patient-derived iPSCs. Takebe and his colleagues devised a special biochemical “recipe” that allowed them to grow liver organoids with sufficient cellular complexity.

As published in Cell Metabolism, the recipe involves a three-step process to coax human iPSCs into forming multi-cellular liver organoids in as little as three weeks. With careful analysis, including of RNA sequencing data, they confirmed that those organoids contained hepatocytes and other supportive cell types. The latter included Kupffer cells, which play a role in inflammation, and stellate cells, the major cell type involved in fibrosis. Fibrosis is the scarring of the liver in response to tissue damage.

Now with a way to make multi-cellular liver organoids, the researchers put them to the test. When exposed to free fatty acids, the organoids gradually accumulated fat in a dose-dependent manner and grew inflamed, which is similar to what happens to people with fatty liver diseases.

The organoids also showed telltale biochemical signatures of fibrosis. Using a sophisticated imaging method called atomic force microscopy (AFM), the researchers found as the fibrosis worsened, they could measure a corresponding increase in an organoid’s stiffness.

Next, as highlighted in the confocal microscope image above, Takebe’s team produced organoids from iPSCs derived from children with a deadly inherited form of fatty liver disease known as Wolman disease. Babies born with this condition lack an enzyme called lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) that breaks down fats, causing them to accumulate dangerously in the liver. Similarly, the miniature liver shown here is loaded with accumulated fat lipids (blue).

That brought researchers to the next big test. Previous studies had shown that LAL deficiency in kids with Wolman disease overactivates another signaling pathway, which could be suppressed by targeting a receptor known as FXR. So, in the new study, the team applied an FXR-targeted compound called FGF19, and it prevented fat accumulation in the liver organoids derived from people with Wolman disease. The organoids treated with FGF19 not only were protected from accumulating fat, but they also survived longer and had reduced stiffening, indicating a reduction in fibrosis.

These findings suggest that FGF19 or perhaps another compound that acts similarly might hold promise for infants with Wolman disease, who often die at a very early age. That’s encouraging news because the only treatment currently available is a costly enzyme replacement therapy. The findings also demonstrate a promising approach to accelerating the search for new treatments for a variety of liver diseases.

Takebe’s team is now investigating this approach for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a common cause of liver failure and the need for a liver transplant. The hope is that studies in organoids will lead to promising new treatments for this liver condition, which affects millions of people around the world.

Ultimately, Takebe suggests it might prove useful to grow liver organoids from individual patients with fatty liver diseases, in order to identify the underlying biological causes and test the response of those patient-specific organoids to available treatments. Such evidence could one day help doctors to select the best available treatment option for each individual patient, and bring greater precision to treating liver disease.

Reference:

[1] Modeling steatohepatitis in humans with pluripotent stem cell-derived organoids. Ouchi R, Togo S, Kimura M, Shinozawa T, Koido M, Koike H, Thompson W, Karns RA, Mayhew CN, McGrath PS, McCauley HA, Zhang RR, Lewis K, Hakozaki S, Ferguson A, Saiki N, Yoneyama Y, Takeuchi I, Mabuchi Y, Akazawa C, Yoshikawa HY, Wells JM, Takebe T. Cell Metab. 2019 May 14. pii: S1550-4131(19)30247-5.

Links:

Wolman Disease (Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center/NIH)

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease & NASH (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Stem Cell Information (NIH)

Tissue Chip for Drug Screening (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Takebe Lab (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Posted In: News

Tags: atomic force microscopy, fatty acids, fatty liver disease, FGF19, fibrosis, hepatitis, hepatocyte, iPS cells, iPSCs, Kupffer cells, liver, liver disease, lysosomal acid lipase, NASH, Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, organoids, rare disease, steatohepatitis, stellate cells, stem cell, Wolman disease