glia – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Basic Researchers Discover Possible Target for Treating Brain Cancer

Posted on May 23rd, 2023 by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

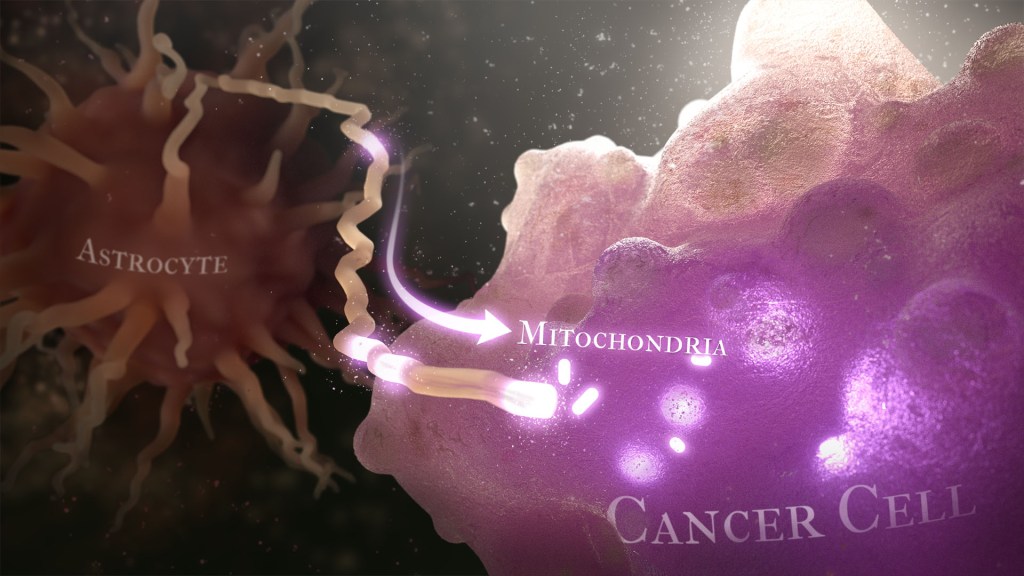

Caption: Illustration of cancer cell (bottom right) stealing mitochondria (white ovals) from a healthy astrocyte cell (left). Credit: Donny Bliss/NIH

Over the years, cancer researchers have uncovered many of the tricks that tumors use to fuel their growth and evade detection by the body’s immune system. More tricks await discovery, and finding them will be key in learning to target the right treatments to the right cancers.

Recently, a team of researchers demonstrated in lab studies a surprising trick pulled off by cells from a common form of brain cancer called glioblastoma. The researchers found that glioblastoma cells steal mitochondria, the power plants of our cells, from other cells in the central nervous system [1].

Why would cancer cells do this? How do they pull it off? The researchers don’t have all the answers yet. But glioblastoma arises from abnormal astrocytes, a particular type of the glial cell, a common cell in the brain and spinal cord. It seems from their initial work that stealing mitochondria from neighboring normal cells help these transformed glioblastoma cells to ramp up their growth. This trick might also help to explain why glioblastoma is one of the most aggressive forms of primary brain cancer, with limited treatment options.

In the new study, published in the journal Nature Cancer, a team co-led by Justin Lathia, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, OH, and Hrvoje Miletic, University of Bergen, Norway, had noticed some earlier studies suggesting that glioblastoma cells might steal mitochondria. They wanted to take a closer look.

This very notion highlights an emerging and much more dynamic view of mitochondria. Scientists used to think that mitochondria—which can number in the thousands within a single cell—generally just stayed put. But recent research has established that mitochondria can move around within a cell. They sometimes also get passed from one cell to another.

It also turns out that the intercellular movement of mitochondria has many implications for health. For instance, the transfer of mitochondria helps to rescue damaged tissues in the central nervous system, heart, and respiratory system. But, in other circumstances, this process may possibly come to the rescue of cancer cells.

While Lathia, Miletic, and team knew that mitochondrial transfer was possible, they didn’t know how relevant or dangerous it might be in brain cancers. To find out, they studied mice implanted with glioblastoma tumors from other mice or people with glioblastoma. This mouse model also had been modified to allow the researchers to trace the movement of mitochondria.

Their studies show that healthy cells often transfer some of their mitochondria to glioblastoma cells. They also determined that those mitochondria often came from healthy astrocytes, a process that had been seen before in the recovery from a stroke.

But the transfer process isn’t easy. It requires that a cell expend a lot of energy to form actin filaments that contract to pull the mitochondria along. They also found that the process depends on growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43), suggesting that future treatments aimed at this protein might help to thwart the process.

Their studies also show that, after acquiring extra mitochondria, glioblastoma cells shift into higher gear. The cancerous cells begin burning more energy as their metabolic pathways show increased activity. These changes allow for more rapid and aggressive growth. Overall, the findings show that this interaction between healthy and cancerous cells may partly explain why glioblastomas are so often hard to beat.

While more study is needed to confirm the role of this process in people with glioblastoma, the findings are an important reminder that treatment advances in oncology may come not only from study of the cancer itself but also by carefully considering the larger context and environments in which tumors grow. The hope is that these intriguing new findings will one day lead to new treatment options for the approximately 13,000 people in the U.S. alone who are diagnosed with glioblastoma each year [2].

References:

[1] GAP43-dependent mitochondria transfer from astrocytes enhances glioblastoma tumorigenicity. Watson DC, Bayik D, Storevik S, Moreino SS, Hjelmeland AB, Hossain JA, Miletic H, Lathia JD et al. Nat Cancer. 2023 May 11. [Published online ahead of print.]

[2] CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2011-2015. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, Boscia A, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. 2018 Oct 1, Neuro Oncol., p. 20(suppl_4):iv1-iv86.

Links:

Glioblastoma (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Brain Tumors (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Justin Lathia Lab (Cleveland Clinic, OH)

Hrvoje Miletic (University of Bergen, Norway)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Posted In: News

Tags: actin filaments, astrocytes, brain cancer, cancer, cancer biology, cell biology, central nervous system cancers, GAPa43, glia, glial cells, glioblastoma, glioblastoma multiforme, mitochondria, mitochondria transfer

Regenerative Medicine: New Clue from Fish about Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on November 15th, 2016 by Dr. Francis Collins

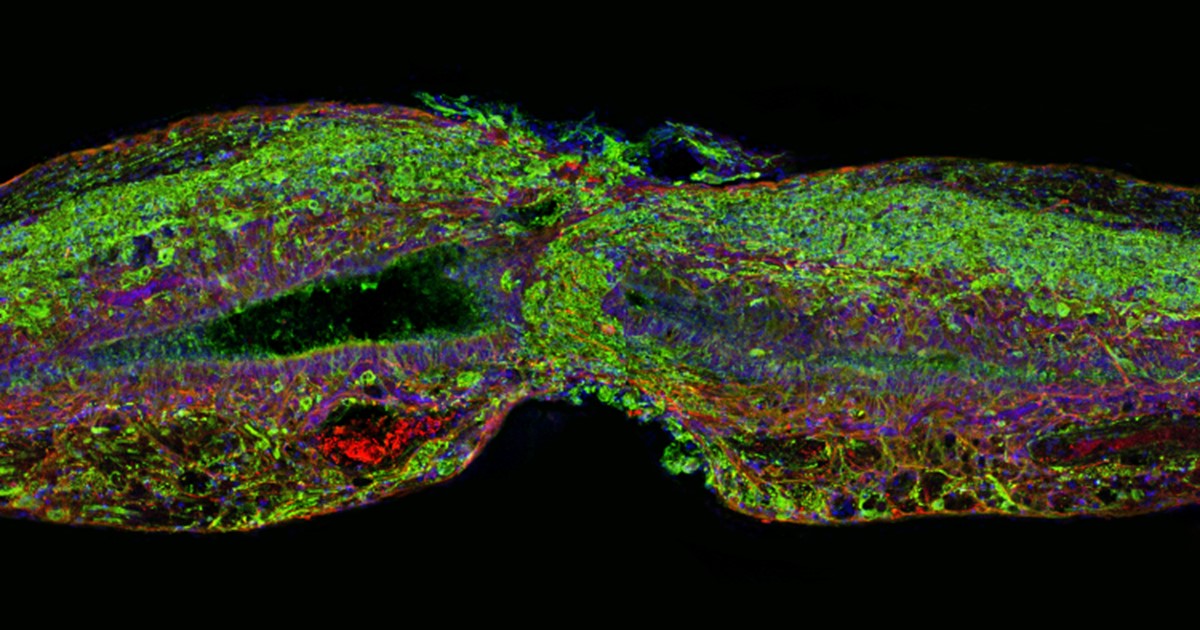

Caption: Tissue section of zebrafish spinal cord regenerating after injury. Glial cells (red) cross the gap between the severed ends first. Neuronal cells (green) soon follow. Cell nuclei are stained blue and purple.

Credit: Mayssa Mokalled and Kenneth Poss, Duke University, Durham, NC

Certain organisms have remarkable abilities to achieve self-healing, and a fascinating example is the zebrafish (Danio rerio), a species of tropical freshwater fish that’s an increasingly popular model organism for biological research. When the fish’s spinal cord is severed, something remarkable happens that doesn’t occur in humans: supportive cells in the nervous system bridge the gap, allowing new nerve tissue to restore the spinal cord to full function within weeks.

Pretty incredible, but how does this occur? NIH-funded researchers have just found an important clue. They’ve discovered that the zebrafish’s damaged cells secrete a molecule known as connective tissue growth factor a (CTGFa) that is essential in regenerating its severed spinal cord. What’s particularly encouraging to those looking for ways to help the 12,000 Americans who suffer spinal cord injuries each year is that humans also produce a form of CTGF. In fact, the researchers found that applying human CTGF near the injured site even accelerated the regenerative process in zebrafish. While this growth factor by itself is unlikely to produce significant spinal cord regeneration in human patients, the findings do offer a promising lead for researchers pursuing the next generation of regenerative therapies.

Tags: connective tissue growth factor a, CTGF, Danio rerio, fish, glia, glial bridges, glial cells, growth factor, model organisms, nerve cells, nervous system, regenerative medicine, self-healing, spinal cord, spinal cord injuries, tissue engineering, tissue regeneration, traumatic injury, wound healing, zebrafish

Mice Learn Better with Help from Human Brain Cells

Posted on March 7th, 2013 by Dr. Francis Collins

Human astrocytes in a mouse brain

Source: Steven Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., University of Rochester Medical Center

What happens when you implant human glia—a type of brain cell that protects and nurtures neurons—into the brains of newborn mice? Well, it turns out these glia mature into multi-talented astrocyte cells that provide nutrients, repair injuries, and modulate signals just like they do in a human brain. They even assume the same complex star shape!

We know the cells in question are indeed human astrocytes because they produce a group of specific proteins, which are tagged with a combination of dyes that together appear yellow in this image. In contrast, the mouse cells are blue.

This all looks very pretty, but you might wonder what impact these human astrocytes have on mouse cognition. Researchers found mice that received the implants were better able to learn and remember than those that didn’t. In short, the human cells seem to have made the mice smarter.

Interestingly, human astrocytes are larger, more complex, and more diverse than their counterparts in other species. So, perhaps these cells may hold some of the keys to our own unique cognitive abilities.

Reference:

Forebrain Engraftment by Human Glial Progenitor Cells Enhances Synaptic Plasticity and Learning in Adult Mice. Xiaoning Han, Michael Chen, Fushun Wang, Martha Windrem, Su Wang, Steven Shanz, Qiwu Xu, Nancy Ann Oberheim, Lane Bekar, Sarah Betstadt, Alcino J. Silva, Takahiro Takano, Steven A. Goldman, and Maiken Nedergaard. Cell Stem Cell 12, 342–353, March 7, 2013.

NIH support: the National Institute of Mental Health; and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke