glial cells – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Basic Researchers Discover Possible Target for Treating Brain Cancer

Posted on May 23rd, 2023 by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

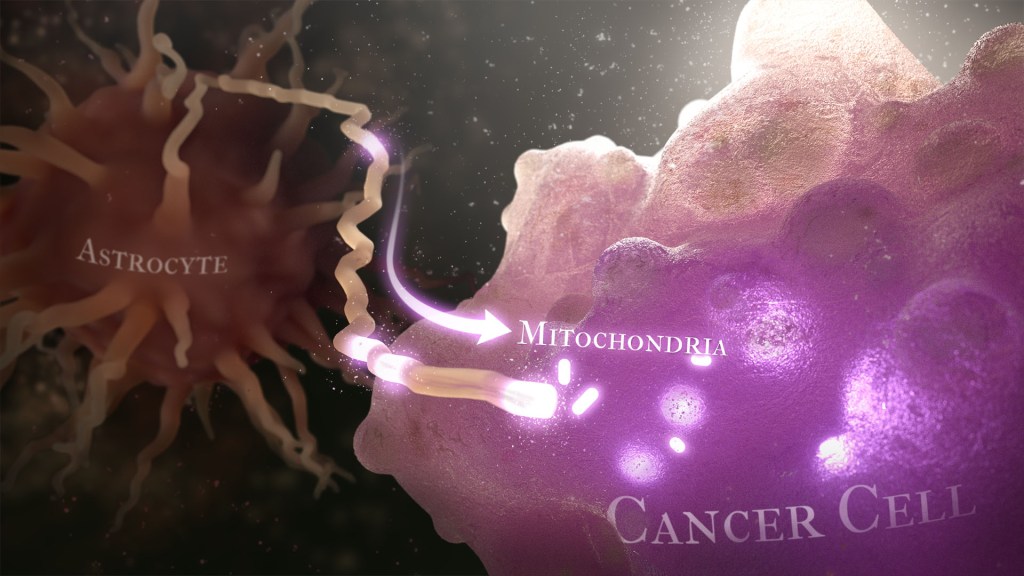

Caption: Illustration of cancer cell (bottom right) stealing mitochondria (white ovals) from a healthy astrocyte cell (left). Credit: Donny Bliss/NIH

Over the years, cancer researchers have uncovered many of the tricks that tumors use to fuel their growth and evade detection by the body’s immune system. More tricks await discovery, and finding them will be key in learning to target the right treatments to the right cancers.

Recently, a team of researchers demonstrated in lab studies a surprising trick pulled off by cells from a common form of brain cancer called glioblastoma. The researchers found that glioblastoma cells steal mitochondria, the power plants of our cells, from other cells in the central nervous system [1].

Why would cancer cells do this? How do they pull it off? The researchers don’t have all the answers yet. But glioblastoma arises from abnormal astrocytes, a particular type of the glial cell, a common cell in the brain and spinal cord. It seems from their initial work that stealing mitochondria from neighboring normal cells help these transformed glioblastoma cells to ramp up their growth. This trick might also help to explain why glioblastoma is one of the most aggressive forms of primary brain cancer, with limited treatment options.

In the new study, published in the journal Nature Cancer, a team co-led by Justin Lathia, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, OH, and Hrvoje Miletic, University of Bergen, Norway, had noticed some earlier studies suggesting that glioblastoma cells might steal mitochondria. They wanted to take a closer look.

This very notion highlights an emerging and much more dynamic view of mitochondria. Scientists used to think that mitochondria—which can number in the thousands within a single cell—generally just stayed put. But recent research has established that mitochondria can move around within a cell. They sometimes also get passed from one cell to another.

It also turns out that the intercellular movement of mitochondria has many implications for health. For instance, the transfer of mitochondria helps to rescue damaged tissues in the central nervous system, heart, and respiratory system. But, in other circumstances, this process may possibly come to the rescue of cancer cells.

While Lathia, Miletic, and team knew that mitochondrial transfer was possible, they didn’t know how relevant or dangerous it might be in brain cancers. To find out, they studied mice implanted with glioblastoma tumors from other mice or people with glioblastoma. This mouse model also had been modified to allow the researchers to trace the movement of mitochondria.

Their studies show that healthy cells often transfer some of their mitochondria to glioblastoma cells. They also determined that those mitochondria often came from healthy astrocytes, a process that had been seen before in the recovery from a stroke.

But the transfer process isn’t easy. It requires that a cell expend a lot of energy to form actin filaments that contract to pull the mitochondria along. They also found that the process depends on growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43), suggesting that future treatments aimed at this protein might help to thwart the process.

Their studies also show that, after acquiring extra mitochondria, glioblastoma cells shift into higher gear. The cancerous cells begin burning more energy as their metabolic pathways show increased activity. These changes allow for more rapid and aggressive growth. Overall, the findings show that this interaction between healthy and cancerous cells may partly explain why glioblastomas are so often hard to beat.

While more study is needed to confirm the role of this process in people with glioblastoma, the findings are an important reminder that treatment advances in oncology may come not only from study of the cancer itself but also by carefully considering the larger context and environments in which tumors grow. The hope is that these intriguing new findings will one day lead to new treatment options for the approximately 13,000 people in the U.S. alone who are diagnosed with glioblastoma each year [2].

References:

[1] GAP43-dependent mitochondria transfer from astrocytes enhances glioblastoma tumorigenicity. Watson DC, Bayik D, Storevik S, Moreino SS, Hjelmeland AB, Hossain JA, Miletic H, Lathia JD et al. Nat Cancer. 2023 May 11. [Published online ahead of print.]

[2] CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2011-2015. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, Boscia A, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. 2018 Oct 1, Neuro Oncol., p. 20(suppl_4):iv1-iv86.

Links:

Glioblastoma (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Brain Tumors (National Cancer Institute/NIH)

Justin Lathia Lab (Cleveland Clinic, OH)

Hrvoje Miletic (University of Bergen, Norway)

NIH Support: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Cancer Institute; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Posted In: News

Tags: actin filaments, astrocytes, brain cancer, cancer, cancer biology, cell biology, central nervous system cancers, GAPa43, glia, glial cells, glioblastoma, glioblastoma multiforme, mitochondria, mitochondria transfer

Gene Therapy Shows Promise Repairing Brain Tissue Damaged by Stroke

Posted on September 24th, 2019 by Dr. Francis Collins

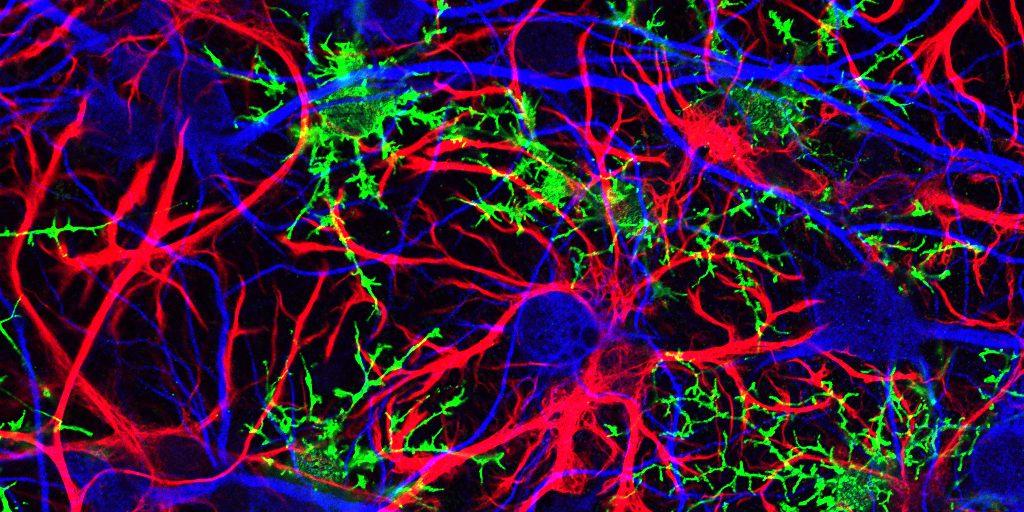

Caption: Neurons (red) converted from glial cells using a new NeuroD1-based gene therapy in mice. Credit: Chen Laboratory, Penn State, University Park

It’s a race against time when someone suffers a stroke caused by a blockage of a blood vessel supplying the brain. Unless clot-busting treatment is given within a few hours after symptoms appear, vast numbers of the brain’s neurons die, often leading to paralysis or other disabilities. It would be great to have a way to replace those lost neurons. Thanks to gene therapy, some encouraging strides are now being made.

In a recent study in Molecular Therapy, researchers reported that, in their mouse and rat models of ischemic stroke, gene therapy could actually convert the brain’s support cells into new, fully functional neurons [1]. Even better, after gaining the new neurons, the animals had improved motor and memory skills.

For the team led by Gong Chen, Penn State, University Park, the quest to replace lost neurons in the brain began about a decade ago. While searching for the right approach, Chen noticed other groups had learned to reprogram fibroblasts into stem cells and make replacement neural cells.

As innovative as this work was at the time, it was performed mostly in lab Petri dishes. Chen and his colleagues thought, why not reprogram cells already in the brain?

They turned their attention to the brain’s billions of supportive glial cells. Unlike neurons, glial cells divide and replicate. They also are known to survive and activate following a brain injury, remaining at the wound and ultimately forming a scar. This same process had also been observed in the brain following many types of injury, including stroke and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

To Chen’s NIH-supported team, it looked like glial cells might be a perfect target for gene therapies to replace lost neurons. As reported about five years ago, the researchers were on the right track [2].

The Chen team showed it was possible to reprogram glial cells in the brain into functional neurons. They succeeded using a genetically engineered retrovirus that delivered a single protein called NeuroD1. It’s a neural transcription factor that switches genes on and off in neural cells and helps to determine their cell fate. The newly generated neurons were also capable of integrating into brain circuits to repair damaged tissue.

There was one major hitch: the NeuroD1 retroviral vector only reprogrammed actively dividing glial cells. That suggested their strategy likely couldn’t generate the large numbers of new cells needed to repair damaged brain tissue following a stroke.

Fast-forward a couple of years, and improved adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV) have emerged as a major alternative to retroviruses for gene therapy applications. This was exactly the breakthrough that the Chen team needed. The AAVs can reprogram glial cells whether they are dividing or not.

In the new study, Chen’s team, led by post-doc Yu-Chen Chen, put this new gene therapy system to work, and the results are quite remarkable. In a mouse model of ischemic stroke, the researchers showed the treatment could regenerate about a third of the total lost neurons by preferentially targeting reactive, scar-forming glial cells. The conversion of those reactive glial cells into neurons also protected another third of the neurons from injury.

Studies in brain slices showed that the replacement neurons were fully functional and appeared to have made the needed neural connections in the brain. Importantly, their studies also showed that the NeuroD1 gene therapy led to marked improvements in the functional recovery of the mice after a stroke.

In fact, several tests of their ability to make fine movements with their forelimbs showed about a 60 percent improvement within 20 to 60 days of receiving the NeuroD1 therapy. Together with study collaborator and NIH grantee Gregory Quirk, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, they went on to show similar improvements in the ability of rats to recover from stroke-related deficits in memory.

While further study is needed, the findings in rodents offer encouraging evidence that treatments to repair the brain after a stroke or other injury may be on the horizon. In the meantime, the best strategy for limiting the number of neurons lost due to stroke is to recognize the signs and get to a well-equipped hospital or call 911 right away if you or a loved one experience them. Those signs include: sudden numbness or weakness of one side of the body; confusion; difficulty speaking, seeing, or walking; and a sudden, severe headache with unknown causes. Getting treatment for this kind of “brain attack” within four hours of the onset of symptoms can make all the difference in recovery.

References:

[1] A NeuroD1 AAV-Based gene therapy for functional brain repair after ischemic injury through in vivo astrocyte-to-neuron conversion. Chen Y-C et al. Molecular Therapy. Published online September 6, 2019.

[2] In vivo direct reprogramming of reactive glial cells into functional neurons after brain injury and in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Guo Z, Zhang L, Wu Z, Chen Y, Wang F, Chen G. Cell Stem Cell. 2014 Feb 6;14(2):188-202.

Links:

Stroke (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

Gene Therapy (National Human Genome Research Institute/NIH)

Chen Lab (Penn State, University Park)

NIH Support: National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health

Posted In: News

Tags: adeno-associated virus, brain, brain injury, gene therapy, gene therapy vector, glial cells, ischemic stroke, neural transcription factor, NeuroD1, NeuroD1-based gene therapy, neurons, neuroscience, replacement neurons, retrovirus, stroke, transcription factor

New Evidence Suggests Aging Brains Continue to Make New Neurons

Posted on April 10th, 2018 by Dr. Francis Collins

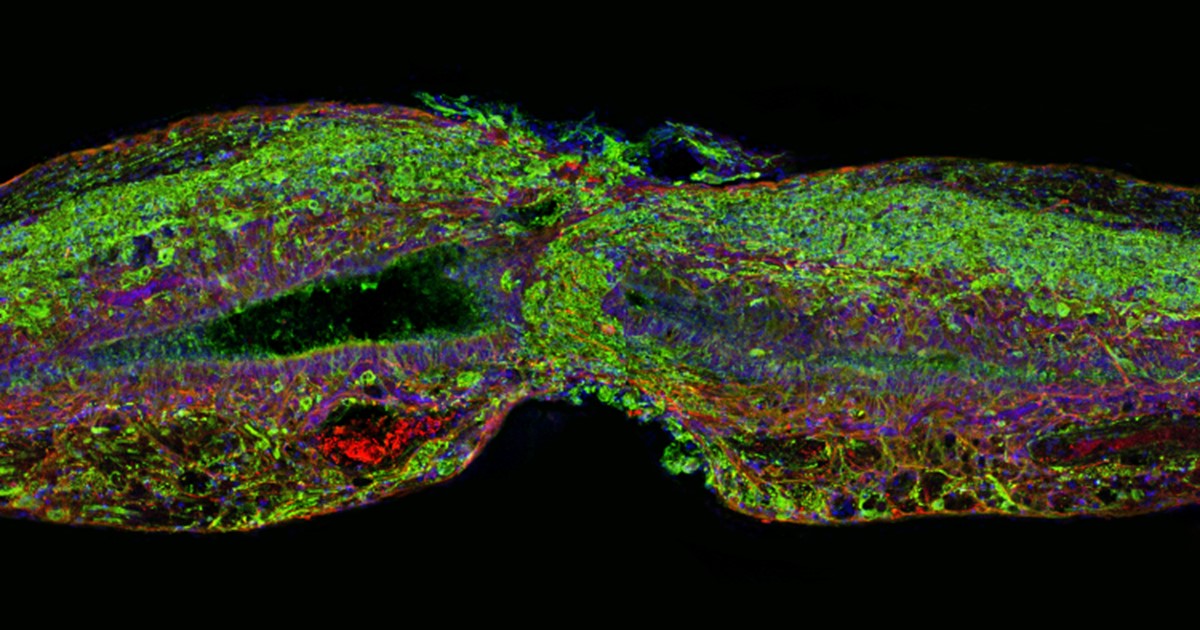

Caption: Mammalian hippocampal tissue. Immunofluorescence microscopy showing neurons (blue) interacting with neural astrocytes (red) and oligodendrocytes (green).

Credit: Jonathan Cohen, Fields Lab, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH

There’s been considerable debate about whether the human brain has the capacity to make new neurons into adulthood. Now, a recently published study offers some compelling new evidence that’s the case. In fact, the latest findings suggest that a healthy person in his or her seventies may have about as many young neurons in a portion of the brain essential for learning and memory as a teenager does.

As reported in the journal Cell Stem Cell, researchers examined the brains of healthy people, aged 14 to 79, and found similar numbers of young neurons throughout adulthood [1]. Those young neurons persisted in older brains that showed other signs of decline, including a reduced ability to produce new blood vessels and form new neural connections. The researchers also found a smaller reserve of quiescent, or inactive, neural stem cells in a brain area known to support cognitive-emotional resilience, the ability to cope with and bounce back from stressful circumstances.

While more study is clearly needed, the findings suggest healthy elderly people may have more cognitive reserve than is commonly believed. However, the findings may also help to explain why even perfectly healthy older people often find it difficult to face new challenges, such as travel or even shopping at a different grocery store, that wouldn’t have fazed them earlier in life.

Posted In: Health, News, Science

Tags: aging, aging brain, angiogenesis, autopsy study, brain, Brain Collection of the New York State Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University, cognition, dentate gyrus, elderly, glial cells, hippocampus, longevity, memory, neural progenitor cells, neural stem cells, neurogenesis, neurology, neurons, neuroplasticity, stereology

Regenerative Medicine: New Clue from Fish about Healing Spinal Cord Injuries

Posted on November 15th, 2016 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: Tissue section of zebrafish spinal cord regenerating after injury. Glial cells (red) cross the gap between the severed ends first. Neuronal cells (green) soon follow. Cell nuclei are stained blue and purple.

Credit: Mayssa Mokalled and Kenneth Poss, Duke University, Durham, NC

Certain organisms have remarkable abilities to achieve self-healing, and a fascinating example is the zebrafish (Danio rerio), a species of tropical freshwater fish that’s an increasingly popular model organism for biological research. When the fish’s spinal cord is severed, something remarkable happens that doesn’t occur in humans: supportive cells in the nervous system bridge the gap, allowing new nerve tissue to restore the spinal cord to full function within weeks.

Pretty incredible, but how does this occur? NIH-funded researchers have just found an important clue. They’ve discovered that the zebrafish’s damaged cells secrete a molecule known as connective tissue growth factor a (CTGFa) that is essential in regenerating its severed spinal cord. What’s particularly encouraging to those looking for ways to help the 12,000 Americans who suffer spinal cord injuries each year is that humans also produce a form of CTGF. In fact, the researchers found that applying human CTGF near the injured site even accelerated the regenerative process in zebrafish. While this growth factor by itself is unlikely to produce significant spinal cord regeneration in human patients, the findings do offer a promising lead for researchers pursuing the next generation of regenerative therapies.

Tags: connective tissue growth factor a, CTGF, Danio rerio, fish, glia, glial bridges, glial cells, growth factor, model organisms, nerve cells, nervous system, regenerative medicine, self-healing, spinal cord, spinal cord injuries, tissue engineering, tissue regeneration, traumatic injury, wound healing, zebrafish