kidney transplantation – NIH Director's Blog (original) (raw)

Immune Resilience is Key to a Long and Healthy Life

Posted on June 20th, 2023 by Lawrence Tabak, D.D.S., Ph.D.

Caption: A new measure of immunity called immune resilience is helping researchers find clues as to why some people remain healthier even in the face of varied inflammatory stressors. Credit: Modified from Shutterstock/Ground Picture

Do you feel as if you or perhaps your family members are constantly coming down with illnesses that drag on longer than they should? Or, maybe you’re one of those lucky people who rarely becomes ill and, if you do, recovers faster than others.

It’s clear that some people generally are more susceptible to infectious illnesses, while others manage to stay healthier or bounce back more quickly, sometimes even into old age. Why is this? A new study from an NIH-supported team has an intriguing answer [1]. The difference, they suggest, may be explained in part by a new measure of immunity they call immune resilience—the ability of the immune system to rapidly launch attacks that defend effectively against infectious invaders and respond appropriately to other types of inflammatory stressors, including aging or other health conditions, and then quickly recover, while keeping potentially damaging inflammation under wraps.

The findings in the journal Nature Communications come from an international team led by Sunil Ahuja, University of Texas Health Science Center and the Department of Veterans Affairs Center for Personalized Medicine, both in San Antonio. To understand the role of immune resilience and its effect on longevity and health outcomes, the researchers looked at multiple other studies including healthy individuals and those with a range of health conditions that challenged their immune systems.

By looking at multiple studies in varied infectious and other contexts, they hoped to find clues as to why some people remain healthier even in the face of varied inflammatory stressors, ranging from mild to more severe. But to understand how immune resilience influences health outcomes, they first needed a way to measure or grade this immune attribute.

The researchers developed two methods for measuring immune resilience. The first metric, a laboratory test called immune health grades (IHGs), is a four-tier grading system that calculates the balance between infection-fighting CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells. IHG-I denotes the best balance tracking the highest level of resilience, and IHG-IV denotes the worst balance tracking the lowest level of immune resilience. An imbalance between the levels of these T cell types is observed in many people as they age, when they get sick, and in people with autoimmune diseases and other conditions.

The researchers also developed a second metric that looks for two patterns of expression of a select set of genes. One pattern associated with survival and the other with death. The survival-associated pattern is primarily related to immune competence, or the immune system’s ability to function swiftly and restore activities that encourage disease resistance. The mortality-associated genes are closely related to inflammation, a process through which the immune system eliminates pathogens and begins the healing process but that also underlies many disease states.

Their studies have shown that high expression of the survival-associated genes and lower expression of mortality-associated genes indicate optimal immune resilience, correlating with a longer lifespan. The opposite pattern indicates poor resilience and a greater risk of premature death. When both sets of genes are either low or high at the same time, immune resilience and mortality risks are more moderate.

In the newly reported study initiated in 2014, Ahuja and his colleagues set out to assess immune resilience in a collection of about 48,500 people, with or without various acute, repetitive, or chronic challenges to their immune systems. In an earlier study, the researchers showed that this novel way to measure immune status and resilience predicted hospitalization and mortality during acute COVID-19 across a wide age spectrum [2].

The investigators have analyzed stored blood samples and publicly available data representing people, many of whom were healthy volunteers, who had enrolled in different studies conducted in Africa, Europe, and North America. Volunteers ranged in age from 9 to 103 years. They also evaluated participants in the Framingham Heart Study, a long-term effort to identify common factors and characteristics that contribute to cardiovascular disease.

To examine people with a wide range of health challenges and associated stresses on their immune systems, the team also included participants who had influenza or COVID-19, and people living with HIV. They also included kidney transplant recipients, people with lifestyle factors that put them at high risk for sexually transmitted infections, and people who’d had sepsis, a condition in which the body has an extreme and life-threatening response following an infection.

The question in all these contexts was the same: How well did the two metrics of immune resilience predict an individual’s health outcomes and lifespan? The short answer is that immune resilience, longevity, and better health outcomes tracked together well. Those with metrics indicating optimal immune resilience generally had better health outcomes and lived longer than those who had lower scores on the immunity grading scale. Indeed, those with optimal immune resilience were more likely to:

- Live longer,

- Resist HIV infection or the progression from HIV to AIDS,

- Resist symptomatic influenza,

- Resist a recurrence of skin cancer after a kidney transplant,

- Survive COVID-19, and

- Survive sepsis.

The study also revealed other interesting findings. While immune resilience generally declines with age, some people maintain higher levels of immune resilience as they get older for reasons that aren’t yet known, according to the researchers. Some people also maintain higher levels of immune resilience despite the presence of inflammatory stress to their immune systems such as during HIV infection or acute COVID-19. People of all ages can show high or low immune resilience. The study also found that higher immune resilience is more common in females than it is in males.

The findings suggest that there is a lot more to learn about why people differ in their ability to preserve optimal immune resilience. With further research, it may be possible to develop treatments or other methods to encourage or restore immune resilience as a way of improving general health, according to the study team.

The researchers suggest it’s possible that one day checkups of a person’s immune resilience could help us to understand and predict an individual’s health status and risk for a wide range of health conditions. It could also help to identify those individuals who may be at a higher risk of poor outcomes when they do get sick and may need more aggressive treatment. Researchers may also consider immune resilience when designing vaccine clinical trials.

A more thorough understanding of immune resilience and discovery of ways to improve it may help to address important health disparities linked to differences in race, ethnicity, geography, and other factors. We know that healthy eating, exercising, and taking precautions to avoid getting sick foster good health and longevity; in the future, perhaps we’ll also consider how our immune resilience measures up and take steps to achieve or maintain a healthier, more balanced, immunity status.

References:

[1] Immune resilience despite inflammatory stress promotes longevity and favorable health outcomes including resistance to infection. Ahuja SK, Manoharan MS, Lee GC, McKinnon LR, Meunier JA, Steri M, Harper N, Fiorillo E, Smith AM, Restrepo MI, Branum AP, Bottomley MJ, Orrù V, Jimenez F, Carrillo A, Pandranki L, Winter CA, Winter LA, Gaitan AA, Moreira AG, Walter EA, Silvestri G, King CL, Zheng YT, Zheng HY, Kimani J, Blake Ball T, Plummer FA, Fowke KR, Harden PN, Wood KJ, Ferris MT, Lund JM, Heise MT, Garrett N, Canady KR, Abdool Karim SS, Little SJ, Gianella S, Smith DM, Letendre S, Richman DD, Cucca F, Trinh H, Sanchez-Reilly S, Hecht JM, Cadena Zuluaga JA, Anzueto A, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 team; Agan BK, Root-Bernstein R, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, He W. Nat Commun. 2023 Jun 13;14(1):3286. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38238-6. PMID: 37311745.

[2] Immunologic resilience and COVID-19 survival advantage. Lee GC, Restrepo MI, Harper N, Manoharan MS, Smith AM, Meunier JA, Sanchez-Reilly S, Ehsan A, Branum AP, Winter C, Winter L, Jimenez F, Pandranki L, Carrillo A, Perez GL, Anzueto A, Trinh H, Lee M, Hecht JM, Martinez-Vargas C, Sehgal RT, Cadena J, Walter EA, Oakman K, Benavides R, Pugh JA; South Texas Veterans Health Care System COVID-19 Team; Letendre S, Steri M, Orrù V, Fiorillo E, Cucca F, Moreira AG, Zhang N, Leadbetter E, Agan BK, Richman DD, He W, Clark RA, Okulicz JF, Ahuja SK. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021 Nov;148(5):1176-1191. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.08.021. Epub 2021 Sep 8. PMID: 34508765; PMCID: PMC8425719.

Links:

COVID-19 Research (NIH)

HIV Info (NIH)

Sepsis (National Institute of General Medical Sciences/NIH)

Sunil Ahuja (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio)

Framingham Heart Study (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH)

“A Secret to Health and Long Life? Immune Resilience, NIAID Grantees Report,” NIAID Now Blog, June 13, 2023

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; National Institute on Aging; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of General Medical Sciences; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Posted In: News

Tags: aging, cardiovascular disease, CD4+, CD8+, COVID-19, Framingham Heart Study, genomics, health disparities, HIV, IHG, immune health grades, immune resilience, immune system, immunity, influenza, kidney transplantation, lifespan, longevity, sepsis, skin cancer, T cells

A Race-Free Approach to Diagnosing Chronic Kidney Disease

Posted on October 21st, 2021 by Dr. Francis Collins

Credit: True Touch Lifestyle; crystal light/Shutterstock

Race has a long and tortured history in America. Though great strides have been made through the work of leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to build an equal and just society for all, we still have more work to do, as race continues to factor into American life where it shouldn’t. A medical case in point is a common diagnostic tool for chronic kidney disease (CKD), a condition that affects one in seven American adults and causes a gradual weakening of the kidneys that, for some, will lead to renal failure.

The diagnostic tool is a medical algorithm called estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). It involves getting a blood test that measures how well the kidneys filter out a common waste product from the blood and adding in other personal factors to score how well a person’s kidneys are working. Among those factors is whether a person is Black. However, race is a complicated construct that incorporates components that go well beyond biological and genetic factors to social and cultural issues. The concern is that by lumping together Black people, the algorithm lacks diagnostic precision for individuals and could contribute to racial disparities in healthcare delivery—or even runs the risk of reifying race in a way that suggests more biological significance than it deserves.

That’s why I was pleased recently to see the results of two NIH-supported studies published in The New England Journal of Medicine that suggest a way to take race out of the kidney disease equation [1, 2]. The approach involves a new equation that swaps out one blood test for another and doesn’t ask about race.

For a variety of reasons, including socioeconomic issues and access to healthcare, CKD disproportionately affects the Black community. In fact, Blacks with the condition are also almost four times more likely than whites to develop kidney failure. That’s why Blacks with CKD must visit their doctors regularly to monitor their kidney function, and often that visit involves eGFR.

The blood test used in eGFR measures creatinine, a waste product produced from muscle. For about the past 20 years, a few points have been automatically added to the score of African Americans, based on data showing that adults who identify as Black, on average, have a higher baseline level of circulating creatinine. But adjusting the score upward toward normal function runs the risk of making the kidneys seem a bit healthier than they really are and delaying life-preserving dialysis or getting on a transplant list.

A team led by Chi-yuan Hsu, University of California, San Francisco, took a closer look at the current eGFR calculations. The researchers used long-term data from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study, an NIH-supported prospective, observational study of nearly 4,000 racially and ethnically diverse patients with CKD in the U.S. The study design specified that about 40 percent of its participants should identify as Black.

To look for race-free ways to measure kidney function, the researchers randomly selected more than 1,400 of the study’s participants to undergo a procedure that allows kidney function to be measured directly instead of being estimated based on blood tests. The goal was to develop an accurate approach to estimating GFR, the rate of fluid flow through the kidneys, from blood test results that didn’t rely on race.

Their studies showed that simply omitting race from the equation would underestimate GFR in Black study participants. The best solution, they found, was to calculate eGFR based on cystatin C, a small protein that the kidneys filter from the blood, in place of the standard creatinine. Estimation of GFR using cystatin C generated similarly accurate results but without the need to factor in race.

The second NIH-supported study led by Lesley Inker, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, came to similar conclusions. They set out to develop new equations without race using data from several prior studies. They then compared the accuracy of their new eGFR equations to measured GFR in a validation set of 12 other studies, including about 4,000 participants.

Their findings show that currently used equations that include race, sex, and age overestimated measured GFR in Black Americans. However, taking race out of the equation without other adjustments underestimated measured GFR in Black people. Equations including both creatinine and cystatin C, but omitting race, were more accurate. The new equations also led to smaller estimated differences between Black and non-Black study participants.

The hope is that these findings will build momentum toward widespread adoption of cystatin C for estimating GFR. Already, a national task force has recommended immediate implementation of a new diagnostic equation that eliminates race and called for national efforts to increase the routine and timely measurement of cystatin C [3]. This will require a sea change in the standard measurements of blood chemistries in clinical and hospital labs—where creatinine is routinely measured, but cystatin C is not. As these findings are implemented into routine clinical care, let’s hope they’ll reduce health disparities by leading to more accurate and timely diagnosis, supporting the goals of precision health and encouraging treatment of CKD for all people, regardless of their race.

References:

[1] Race, genetic ancestry, and estimating kidney function in CKD. Hsu CY, Yang W, Parikh RV, Anderson AH, Chen TK, Cohen DL, He J, Mohanty MJ, Lash JP, Mills KT, Muiru AN, Parsa A, Saunders MR, Shafi T, Townsend RR, Waikar SS, Wang J, Wolf M, Tan TC, Feldman HI, Go AS; CRIC Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2021 Sep 23.

[2] New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Wang D, Sang Y, Crews DC, Doria A, Estrella MM, Froissart M, Grams ME, Greene T, Grubb A, Gudnason V, Gutiérrez OM, Kalil R, Karger AB, Mauer M, Navis G, Nelson RG, Poggio ED, Rodby R, Rossing P, Rule AD, Selvin E, Seegmiller JC, Shlipak MG, Torres VE, Yang W, Ballew SH,Couture SJ, Powe NR, Levey AS; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. N Engl J Med. 2021 Sep 23.

[3] A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN Task Force on Reassessing the Inclusion of Race in Diagnosing Kidney Disease. Delgado C, Baweja M, Crews DC, Eneanya ND, Gadegbeku CA, Inker LA, Mendu ML, Miller WG, Moxey-Mims MM, Roberts GV, St Peter WL, Warfield C, Powe NR. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021 Sep 22:S0272-6386(21)00828-3.

Links:

Chronic Kidney Disease (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Explaining Your Kidney Test Results: A Tool for Clinical Use (NIDDK)

Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study

Chi-yuan Hsu (University of California, San Francisco)

Lesley Inker (Tufts Medical Center, Boston)

NIH Support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Posted In: News

Tags: African American health, African Americans, blacks, chronic kidney disease, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study, CKD, creatinine, CRIC Study, cystatin C, diagnostics, eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate, genetics, GFR, glomerular filtration rate, health disparities, kidney dialysis, kidney disease, kidney failure, kidney transplantation, kidneys, muscle, precision health, precision medicine, race, renal failure

Seven Questions for a Rare Disease Warrior

Posted on February 27th, 2020 by Dr. Francis Collins

Caption: David Fajgenbaum (right) and I pose for a photo a few years ago in Philadelphia.

Credit: National Disease Research Interchange, Philadelphia

Tomorrow is Rare Disease Day at NIH, marking the 12th year that this annual event has been held on the NIH campus. Similar gatherings have been organized independently around the world this week, all to raise awareness for the nearly 7,000 rare diseases, some affecting just a few dozen people. But, collectively, rare diseases are hardly rare. One in 10 Americans has a rare disease (defined as affecting 200,000 or fewer individuals in the US), and about half are children. Without needed treatments, about 30 percent of these children will die by age 5.

To join everyone in raising awareness, I wanted to feature on my blog a unique perspective about rare diseases, and David Fajgenbaum certainly has one. Fajgenbaum is an immunologist and NIH grantee at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. When Fajgenbaum isn’t running studies or clinical trials, he must remain vigilant of his own health. Fajgenbaum has a rare disease called idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD), and this devastating condition, which emerged while he was in medical school, nearly claimed his life several times.

Now 34 years old and in a long remission, Fajgenbaum can discuss rare diseases as a doctor, as a patient, as a researcher, and as an advocate. His personal journey, published in his recent book Chasing My Cure, is a gripping read. Fajgenbaum was kind enough to answer a few of my questions on rare diseases and share some of his lessons learned.

The last time that I saw you, David, you looked great. How long have you been in remission?

I have been in remission for 73.83 months. I say 73.83, because I know that I can’t round up—I may relapse tomorrow. But I also refuse to round down because so many colleagues and I have worked so hard for every day of remission for me and other patients with my disease.

For me, every day is particularly special, because I never thought that I would be alive this long. As you know, I became deathly ill during medical school in 2010 and even had my last rites read to me when my doctors didn’t think I would survive. I was eventually diagnosed with idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD), which is like a deadly cross between cancer and autoimmunity. Chemotherapy saved my life, but I would go on to have four near-death relapses.

After one of those relapses, I got out of the hospital and dedicated my life to conducting iMCD research and co-founded the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network (CDCN). Later, I identified a particular cellular pathway called mTOR that was highly active in my samples. I began testing on myself an mTOR inhibitor [sirolimus]—developed 30 years before and approved for kidney transplantation but never considered for iMCD. It’s this drug that has kept me in remission for the last 73.83 months and helped other people. During this time, I’ve been able to marry my wife, have a daughter, help launch a new center at Penn specializing in rare diseases, and write a book to share my personal journey with others.

As a physician-scientist and as a person with a rare disease, what have you learned about the biomedical research process?

I’ve learned so much, but I’d like to highlight three lessons in particular. First, we must leverage all perspectives to prioritize research and give us the best chance of translating research into meaningful breakthroughs. The traditional approach to rare disease research involves a subset of researchers within a rare disease field submitting their best ideas for funding and a panel selecting the best applicant.

Through the CDCN, we’ve spearheaded a new approach called the Collaborative Network Approach, where we crowdsource research questions from the entire community of patients, physicians, and researchers (not just a subset of researchers) and then recruit the best researchers in the world (not just from within the Castleman disease field) to perform the prioritized studies. We’re now working to improve and spread this approach to other diseases.

Second, collaboration between all players is critical. Patient advocacy groups are uniquely positioned to serve as the glue between all stakeholders. Researchers and physicians need to share ideas, data, and samples with one another. Patients need to be actively involved in research question prioritization and study design. Biopharma and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) need to be engaged early in the process of research discoveries and drug development.

Third, we must leverage all 1,500-plus, existing FDA-approved drugs to help as many patients without any options as quickly as possible. As you know, less than 5 percent of the nearly 7,000 rare diseases have an FDA-approved therapy, but many diseases share similar cellular and genetic defects that could make them susceptible to the same drugs. I’m literally alive today thanks to a drug developed for another disease. How many of the drugs approved for one disease may be effective for many of the 7,000 diseases without any? I don’t know the answer, but I hope we can begin to address this important question and incentivize repurposing.

In your experience, how can people with rare diseases help to advance progress for their conditions?

There is so much work to be done for so many rare diseases. Sometimes it can feel so overwhelming and like “what can I really do?”

But I’ve learned that there are so many ways that we can each contribute and so many incredible examples of advocates who have made a difference for themselves and those that they love. Cystic fibrosis and chordoma are just two of many examples where patient-advocates have been critical partners in transforming their diseases.

People with rare diseases can raise funds for research. Every dollar truly counts. We can work with existing organizations for our disease to ensure that those funds are distributed as efficiently and effectively as possible. If there are major gaps within our rare disease fields that aren’t being addressed by existing organizations, we can start new rare disease organizations (but we should try to avoid this whenever possible). We can contribute samples and data towards research, participate in clinical trials, and share with other patients about our experiences. We can advocate for new drug development and repurposing already-FDA approved drugs for our diseases.

What would you tell other researchers who are studying rare diseases?

I would tell other rare disease researchers that you are doing such important work. You give us hope that a treatment can be identified that will change our lives. It’s an incredible responsibility and incredibly stressful. There are unfortunately far too many scientific questions and diseases with major unmet need for any of us to compete over the use of samples and data. We have to share these within our fields. And we must also work together across rare diseases. We can’t continue to reinvent the wheel; we must share learnings with one another

I enjoyed doing the CastleMan Warrior Flex with you. Tell us more about what it represents?

Doing the CastleMan Warrior Flex with you is one of my favorite pictures. In fact, it’s hanging up in my office.

Castleman disease was named after Dr. Benjamin Castleman, who first described our disease in 1954. We have repurposed the “Castleman” name to be a “CastleMan Warrior” (below is our cartoon mascot). We do the “CastleMan Warrior” Flex to raise awareness for Castleman disease and rare diseases generally—we’re all warriors in the rare disease space.

Credit: David Fejgenbaum/National Disease Research Interchange, Philadelphia

What are your future plans as a rare disease advocate and as a researcher?

We’ve made a lot of progress for Castleman disease: we’ve advanced our findings about mTOR towards a clinical trial, gained approval for the treatment siltuximab for iMCD, developed diagnostic criteria and treatment guidelines, and invested about 1.5millionintoCastlemandiseaseresearch,whichhasledtoover1.5 million into Castleman disease research, which has led to over 1.5millionintoCastlemandiseaseresearch,whichhasledtoover7 million in additional funding from other sources.

But we still have important work ahead of us. The treatments sirolimus and siltuximab work for only a portion of all iMCD patients. We need to identify more effective treatments for all forms of Castleman disease.

I will continue to study Castleman disease and other diseases at the intersection of autoimmunity and oncology to gain insights into how the immune system works in myriad diseases. In parallel, I will continue to advocate for the adoption of the “Collaborative Network Approach” to crowdsource all stakeholder perspectives as well as for new models for drug repurposing.

Any other issues that you’d like to address?

I feel a responsibility to share with the world the lessons that I’ve learned about life from nearly dying five times. This is a major reason that I wrote my book.

One lesson that I think about a lot is related to my growing up playing football. Some of my games were extended into an overtime period to decide the outcome. In overtime, every second counts and you’re totally focused on what’s important. I’ve lived with that exact same feeling ever since I had my last rites read to me.

I’ve also learned that humor can be incredibly powerful. You may think that a good laugh may be the last thing that you’d want to do when you’re dying in the ICU. But laughing with the people that I love actually helped me feel like I could transcend my illness, and it helped to connect us.

My greatest regrets on my deathbed were not things that I had done or said. I regretted what I didn’t do or didn’t say and that I would no longer be able to do. I now follow the motto: “Think It, Do It.” In other words, we should reflect on what we’re hoping for and then turn our hopes into action.

Finally, I’ve learned that it really takes a strong team to make a difference in the world, especially against diseases. If it was just me on my own, we would have made less than 1 percent of the progress that’s been achieved. I hope that all rare disease warriors will join together into strong teams, armies even, and make a difference in the world.

Links:

Rare Disease Day at NIH 2020 (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH)

Posted In: News

Tags: Castleman disease, Castleman Disease Collaborative Network, CastleMan Warrior Flex, Chasing My Cure, chemotherapy, David Fajgenbaum, ideopathic multicentric Castleman disease, iMCD, kidney transplantation, mTOR, rare disease, Rare Disease Day, siltuximab

Pursuing Precision Medicine for Chronic Kidney Disease

Posted on December 15th, 2015 by Dr. Francis Collins

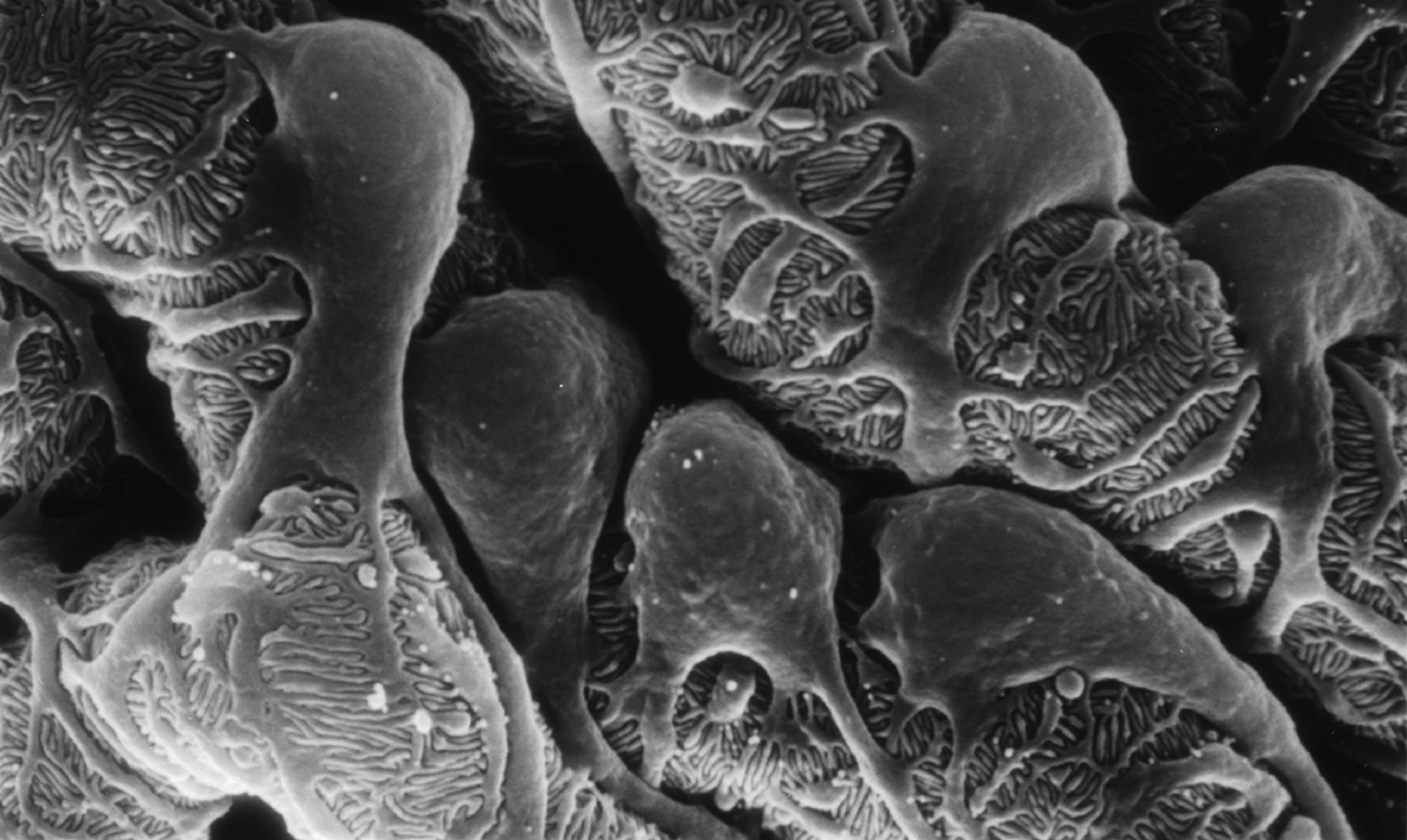

Caption: Scanning electron micrograph showing a part of one of the kidney’s glomerular filters, which are damaged in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The cells with the lacy cytoplasmic extensions are called podocytes.

Credit: Kretzler Lab, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor

Every day, our kidneys filter more than 30 gallons of blood to allow excretion of molecules that can harm us if they build up as waste. But, for more than 20 million Americans and a growing number of people around the world, this important function is compromised by chronic kidney disease (CKD) [1]. Some CKD patients are at high risk of progressing to actual kidney failure, treatable only by dialysis or kidney transplants, while others remain generally healthy with stable kidney function for many years with minimal treatment.

The dilemma is that, even when CKD is diagnosed early, there’s been no good way to predict which individuals are at high risk for rapid progression. Those individuals would potentially benefit from more intensive measures to slow or prevent kidney failure, such as drug regimens that tightly control blood pressure and/or blood glucose. So, I’m pleased to report that NIH-funded researchers have made some progress toward developing more precise strategies for identifying individuals at high risk for kidney failure. In recent findings published in Science Translational Medicine [2], an international research team has identified a protein, easily detectable in urine, which appears to serve as an early warning sign of CKD progression.

A wide range of conditions, from diabetes to hypertension to the autoimmune disease lupus, can contribute to the gradual loss of kidney function seen in people with CKD. But research suggests that once kidney damage reaches a critical threshold, it veers off to follow a common downhill course, driven by shared cell signaling pathways and almost independent of the conditions causing it. If there was an easy, reliable way to determine when a CKD patient’s kidneys are approaching this threshold, it could open the door to better strategies for protecting them from kidney failure.

With this need in mind, a team, led by Matthias Kretzler and Wenjun Ju of the University of Michigan, began analyzing gene activity in kidney biopsy samples donated by 164 CKD patients and stored in the European Renal cDNA Bank. Specifically, the researchers looked for patterns of gene activity that corresponded with the patients’ estimated glomerular filtration rates, an indicator of renal function frequently calculated as part of a routine blood workup. Their first pass produced a list of 72 genes that displayed varying levels of activity that corresponded to differences in the patients’ estimated glomerular filtration rates. Importantly, the activity of many of those genes is also increased in cell signaling pathways thought to drive CKD progression.

Further study in two more groups of CKD patients, one from the United States and another from Europe, whittled the list down to three genes that best predicted kidney function. The researchers then zeroed in on the gene that codes for epidermal growth factor (EGF), a protein that, within the kidney, seems to be produced specifically in tubules, which are key components of the waste filtration system. Because EGF appears to enhance tubular repair after injury, researchers had a hunch that it might serve as a positive biomarker of tubular function that could be combined with existing tests of glomerular filtration to detect progression of CKD at an earlier stage.

In groups of CKD patients from the United States and China, the researchers went on to find that the amount of EGF in the urine provides an accurate measure of the protein’s activity in the kidney, making it a promising candidate for a simple urine test. In fact, CKD patients with low levels of EGF in their urine were four times more likely than those with higher EGF levels to have their kidney function worsen within a few years.

These lines of evidence suggest that, if these findings are replicated in additional studies, it may be possible to develop a simple EGF urine test to help identify which individuals with CKD would benefit the most from aggressive disease management and clinical follow-up. Researchers also plan to explore the possibility that such a urine test might prove useful in the early diagnosis of CKD, before there are any other indications of kidney disease. These are very promising new findings, but much remains to be done before we can think of applying these results as standard of care in the clinic. For example, the EGF work needs to be replicated in larger groups of CKD patients, as well as CKD patients with diabetes.

Beyond their implications for CKD, these results demonstrate the power of identifying new biologically important indicators directly from patients and then testing them in large, diverse cohorts of people. I look forward to the day when these sorts of studies will become possible on an even larger scale through our U.S. Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort.

References:

[1] National Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet, 2014. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[2] Tissue transcriptome-driven identification of epidermal growth factor as a chronic kidney disease biomarker. Ju W, Nair V, Smith S, Zhu L, Shedden K, Song PX, Mariani LH, Eichinger FH, Berthier CC, Randolph A, Lai JY, Zhou Y, Hawkins JJ, Bitzer M, Sampson MG, Thier M, Solier C, Duran-Pacheco GC, Duchateau-Nguyen G, Essioux L, Schott B, Formentini I, Magnone MC, Bobadilla M, Cohen CD, Bagnasco SM, Barisoni L, Lv J, Zhang H, Wang HY, Brosius FC, Gadegbeku CA, Kretzler M; ERCB, C-PROBE, NEPTUNE, and PKU-IgAN Consortium. Sci Transl Med. 2015 Dec 2;7(316):316ra193.

Links:

Chronic Kidney Disease: What Does it Mean to Me? (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/NIH)

Personalized Molecular Nephrology Research Laboratory (University of Michigan)

C-Probe (University of Michigan)

Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort Program (NIH)

NIH Support: National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Tags: C-PROBE, chronic kidney disease, CKD, diabetes, dialysis, EGF, epidermal growth factor, ERCB, glomerular filtration rate, glomeruli, hypertension, kidney, kidney damage, kidney disease, kidney failure, kidney transplantation, kidney tubules, lupus, nephrology, NEPTUNE, personalized nephrology, PKU-IgAN Consortium, precision medicine, Precision Medicine Initiative Cohort Program, transcriptomics, urine test